|

ANATOMY OF A FALL [ANATOMIE D'UNE CHUTE]

One of the most unexpected highlights of 2023, director and co-writer Justine Triet’s utterly enthralling drama revolves around Sandra Voyter (a superb Sandra Hüller in her first of two appearances on this list), a woman whose husband Samuel falls to his death from the upstairs window of their isolated mountain chalet. Following a detailed investigation by the police, a court case begins to determine whether Samuel accidentally fell or was pushed from the building by his wife. On paper, this must read like a recipe for a possibly worthy but ultimately staid experience, but Anatomy of a Fall is anything but, developing as it does into an utterly compelling courtroom drama in which Sandra’s guilt or innocence is never clear cut, and by visualising key elements of the testimonies and evidence, Triet breaks free of the locational restrictions of the trial that is the dominant component of the enthralling and frequently surprising narrative.

LA CHIMERA

Immediately following his release from prison, weathered English archaeologist Arthur (Josh O'Connor, looking at times like the weary and weatherbeaten twin brother of comedian Jon Richardson) is reluctantly reunited with the cheerful band of local rogues with whom he previously associated. It turns out that Arthur has an almost supernatural ability to locate hidden graves, which the group then raids for whatever archaeological treasures may have been secreted within, an illegal activity that sees them constantly having to stay one step ahead of the law and a rival grave-robbing gang.

A bonafide triumph of atmosphere, tone and character over story, this hauntingly sorrowful work from director Alice Rohrwacher really stayed with me for days after my first viewing, and could almost be regarded as the mystical-realist flipside to the bigger budgeted likes of Indiana Jones and Lara Croft. And maybe it’s just me and my faltering vision, but I genuinely didn’t recognise Isabella Rossellini on her first appearance as Flora, the ageing mother of Arthur’s lost love and the one person he continues to regard as his friend.

CIVIL WAR

America has dissolved into civil war, with an unstable government in violent conflict with an unlikely but – at least in terms of audience allegiance – strategically smart alliance of the states of California and Texas. Celebrated combat photographer Lee Smith (clearly based on real-world war photographer Lee Miller, who is shrewdly name-checked here) and her partner Joel are heading for Washington with the aim of interviewing the beleaguered President, a journey on which they are joined by veteran New York Times journalist Sammy, and Jessie, a young wannabe photographer that Lee reluctantly takes under her wing.

As it was with Gareth Edwards’ 2010 Monsters, their journey is ultimately about the people and the groups that they encounter and interact with as they make their way through potentially treacherous warring territory. It’s here that Ex Machina and Annihilation director Alex Garland's film delivers its most impactful hammer blows, with breathlessly realistic scenes of combat and one of the tensest sequences I watched all year, when the four are effectively held hostage by a rogue racist militia group, whose leader is played with terrifying nonchalance by an uncredited Jesse Plemons. The soundtrack is one of the best I’ve ever heard, with an ex-soldier friend of mine stating that it contained the most realistic gunshot sounds he’d ever heard in a film. It’s a compelling, hard-hitting and worryingly relevant work that loses just a little of its edge when a breathlessly realistic combat scene is followed by montage cut to a needle-drop song, a perhaps too-common film convention that undercuts the documentary feel of the preceding scene and reminded me that I was watching a constructed drama. I can’t be alone in predicting that the master would eventually find herself slipping into the shadow of her apprentice, but it does give rise to a memorable final image.

Film review [Camus] >>

CONCLAVE

|

A drama about a group of archbishops meeting to decide the next Pope? No thanks. One directed by Edward Berger, whose German language version of All Quiet on the Western Front was one of my favourite films of 2022, and adapted by Peter Straughan – who scored with his waste-free compression of Len Deighton’s Tinker, Taylor, Soldier, Spy (2011) – from a novel by Robert Harris? Okay, maybe. How about one with a cast headed by Ralph Fiennes, Stanley Tucci, John Lithgow and Isabella Rossellini that was being enthusiastically praised for its dialogue, its performances and its twisty plot? Wait a minute, twisty plot? What is this, an Agatha Christie-style thriller? Well, in a way, yes. Indeed, its plot was jokingly summed up by critic Brian Tallerico – who really liked the film, I should note – as “12 Angry Popes.” Oh, how I wish I’d come up with that one. And to my surprise, I was riveted, not just by the gradual uncovering of secrets that start knocking the previously hopeful archbishops off the list of candidates, but unexpectedly – and despite myself – by the peculiarities of the ritual-driven process of the election. Progressive views are aired in the face of the old school bigotry espoused by Sergio Castellitto’s Archbishop Tedesco, and although I predicted the final outcome of the increasingly troubled election at an early stage, I was still caught out by a final twist that I’d like to think represented the dawn of a new age of enlightenment for a religion that in so many ways is still stuck hopelessly in the past.

FURIOSA: A MAD MAX SAGA

Rather than try to top the almost relentless and often awe-inspiring onslaught of physical action of his superb 2015 Mad Max: Fury Road, writer-director Miller and one of his Fury Road co-writers, Nick Lathouris, wisely opted instead to create a prequel that logically plays more like a build-up to the earlier film than an attempt to out-race and out-combat it. I’m usually not a fan of origin stories, but if there was one character from the cinema of recent years that just cried out for one it was Furiosa, the earlier movie’s tough and enigmatic heroine, who is compellingly played here both by Anya Taylor-Joy (who gives Emma Stone a run for her money when it comes to her large and expressive eyes) and every bit as arrestingly as a youngster by Alyla Browne.

Miller’s post-apocalyptic world-building is once again phenomenal, and the story of how a carefree young girl from a peaceful wasteland commune is transformed by misfortune, hardship, resilience and determination into the resourceful wasteland warrior she was to become had me utterly gripped from the opening scene, and when it does come, the action is blisteringly staged. I really liked Chris Hemsworth’s turn as Dementus, and I know this is going to be a controversial opinion, but Jacob Tomuri feels even closer to how I imagined Max Rockatansky would look and sound when he got older than Tom Hardy does in Fury Road, and I really liked Hardy in that film. Just as well, really, as apparently he’s returning to the role in Miller’s upcoming Mad Max: The Wasteland. I await with baited breath.

GODZILLA MINUS ONE [GOJIRA]

In anticipation of the 70th anniversary of the release of director Honda Ishirō’s subgenre-defining 1954 Godzilla [Gojira], writer, director and visual effects supervisor Yamazaki Takashi delivered a Godzilla movie that equalled and at times even topped the original in the depth of its characterisations and story, the strength of its subtext, and the sheer, jaw-droppingly convincing spectacle of its action scenes. A key lesson Yamazaki learned from Honda is to not build his film around his title creature, but to have it play a metaphorical role in a very human drama, the focus of which here is survivor guilt and its personal and sometimes tragic consequences.

After losing his nerve and landing his plane at a repair station in the last stages of WWII, kamikaze pilot Shikishima Koichi freezes up when the station is attacked by a giant dinosaur-like monster that the locals call Godzilla, with the result that almost the entire garrison is wiped out. When Koichi returns to his devastated neighbourhood in Tōkyō, he is condemned for his cowardice by a female neighbour, then by chance ends up partnered with the young and resourceful Noriko, who is caring for an orphaned baby she rescued from the rubble. Koichi eventually lands work aboard a small minesweeper tasked with clearing American mines from the waters around Tōkyō, but when the US nuclear tests at Bikini Atoll cause Godzilla to mutate, the creature responds by launching a hugely destructive attack on the city.

As a long-standing fan of Honda’s original, I had high hopes for this movie but it actually surpassed them in every respect. A human drama that pushes all the right emotional buttons, fully committed and engaging performances (I particularly enjoyed the delightfully mismatched members of the minesweeper crew), the multilayered commentary on postwar Japan and cold war politics, and Takahashi’s ability to effortlessly move between touching personal scenes and ones of epic scale make this one of the movie treasures of the year. The crowning glory is the glorious and always convincing effects work, meticulously recreating the Tōkyō of the period and then having torn apart by the claws, tail and atomic blast breath of a creature whose gigantic size and destructive power are conveyed like never before, and helped bag the film the year’s Best Visual Effects Oscar. And all this on an estimated budget of between $10–15 million, a small fraction of what similarly effects-heavy movie would cost to produce in Hollywood today.

My relationship with this remarkable movie goes beyond my enjoyment and appreciation of the film itself. My partner is a huge fan of the Godzilla films, having grown up watching them in her native Japan, and adored this latest entry in the franchise. This was reignited when we travelled to Ōsaka last October and paid a visit to Yodobashi Camera, an absolutely massive multistorey electronic goods store (with some very good restaurants on the top floor, I should add), which had the Tōkyō attack scene from Godzilla Minus One playing on a 72” TV with a surround sound speaker setup and a seat in which you could experience the sound and vision at its best. Then, a few days later, we were in the huge Daimaru department store when we came across an area devoted solely to Godzilla memorabilia, the highlight of which was a glorious, 2-metre+ high display model of the creature from Yamazaki’s film. Did we buy some of the probably overpriced items on offer? Absolutely. My partner’s only regret – and this really bugs her to this day – was that we wouldn’t still be in the county for the 2024 Ōsaka Godzilla Expo, a comprehensive treat for fans of the series.

You can find more details of the Expo here: https://mykaiju.com/godzilla-expo-osaka/

You can also watch a news report about the Daimaru Godzilla store (it’s in Japanese with no subtitles, but you’ll get the drift) here: https://youtu.be/hDZj-ZKNqZE?si=tdOEzfON_t2ZLMPJ.

THE HOLDOVERS

One feature of some of the films that have most entranced me during the past couple of years is that their premise is not one that I would automatically respond to, and were it not for the buzz created by some excellent word-of-mouth, I’m not sure how long it would have taken me to catch up with director Alexander Payne’s The Holdovers, despite my fondness for his first two full-length features, Citizen Ruth (1996) and Election (1999). As anyone who knows me will doubtless testify, the prospect of film about a New England boarding school student who finds himself stuck at this prestigious academy over the 1970 Christmas break with the head cook and its most irascible and widely disliked professor is not one that I would normally get fired up by. But oh, what an exquisite, bittersweet joy of a film this is.

A sharp and gloriously barbed first feature film script by former TV writer David Hemingson gives one of the lead players of Payne’s 2004 hit Sideways, Paul Giamatti, the role of a lifetime as Paul Hunham, the school’s self-satisfied, sardonic Ancient Civilisations teacher, but he’s matched all the way by Da'Vine Joy Randolph as wearily tolerant head cook Mary Lamb, and talented first-timer Dominic Sessa as disgruntled and rebellious student Angus Tully. That the initially fractious relationship between these three mismatched characters with gradually thaw as surely as the snow that traps them in the school is a given, but the process is handled with tremendous wit, genuine warmth, and real heart. For cineastes, there is an extra pleasure in the execution, with Payne working with In Bruges cinematographer Eigil Bryld and colourist Joe Gawler to give this digitally shot film the look of one made in the year in which it is set – even the poster looks as if it was designed in the early 70s.

HOW TO BLOW UP A PIPELINE

A diverse collection of environmental activists meets at a remote location to prepare and execute a plan to sabotage a West Texas oil pipeline with an explosive device of their own making. And that is the essence of the plot of Cam director Daniel Goldhaber’s riveting second feature, loosely adapted by Goldhaber, Jordan Sjol and Ariela Barer (who also plays one of the lead roles here) from the non-fiction book of the same name by Andreas Malm.

When they first meet up, the disparate members of this group of would-be saboteurs come across as a surprising and even unlikely alliance, but as they plan their operation and embark on the perilous process of constructing the bomb, the events that have driven them each to the point of violent action are explored in a series of revealing flashbacks that in no way disrupt the film’s finely focussed forward momentum. And those backstories have lost none of their relevance and bite, and if anything have become more pertinent in recent months, notably that Theo, who cannot afford the treatment for his toxic chemical-induced terminal cancer because of the profit-driven nature of the American healthcare system. Need I say more?

What in theory should hamstring the film’s attempt to build tension, but instead ends up amplifying it, is Goldhaber’s decision to take a seemingly neutral stance and simply observe the operation like an inquisitive documentarian. As we spend time with the activists and their backstories are revealed, a bond is formed that allows us to view the task ahead through their eyes, but also to understand that the destructive might of the fossil fuel industry is not going to be stopped by this one act of defiance. It’s an impeccably made, utterly engrossing drama whose moments of tension are up there with the best of its year, and despite its earlier air of neutrality, the moving parting montage still felt to me like a sly call to action.

HUNDREDS OF BEAVERS

Talk about a film that I almost dismissed on the basis of its title and poster alone. I don’t have kids, so am not forced to sit through those dumb movies they tend to want to watch four times a week, and on the surface this looked like just that kind of film. Boy, was I wrong about that. I won’t pad this out by relating the series of events that led me to eagerly hunting out Hundreds of Beavers after all, just know that this is the film that knocked Barbie into second place when it comes to the most fun I had watching a movie all year.

Directed and co-written by Mike Cheslik, it stars co-writer Ryland Brickson Cole Tews as successful applejack farmer and producer Jean Kayak, whose livelihood is destroyed by wood-munching beavers, leaving him to fight for survival in the snowy wilderness and seek his revenge against these animals whilst trying to win the hand of the pretty daughter of a grumpy merchant trader. I realise that this summary only seems to reaffirm my original conviction that the film was essentially a live-action cartoon for kids, but here it really is all in the execution, which is genuinely inspired. Just as The Holdovers was filmed and edited to look like a film made in the 1970s, so Hundreds of Beavers masquerades as a newly rediscovered silent slapstick comedy, one that combines live action footage shot on a Panasonic GH5 DSLR (my own camera of choice) with graphical backgrounds and props, and home-brewed animation, with the compositing and effects work done by Cheslik himself on Adobe After Effects.

There are only a couple of words of dialogue throughout, small animals are created through puppetry, while the larger creatures are played by humans in baggy animal costumes. And it’s utterly hilarious, prompting uproarious laughs throughout from this unprepared viewer, and if it seems to be taking a serious turn midway after a riotously funny first act, stick with it for the semi-surreal and brilliantly bonkers finale, when visual gags are fired at you at gatling gun speed. Made on a budget of just $150,000, which took Cheslik several years to raise in full – $10,000 of which was spent on Beaver costumes bought from a Chinese mascot website and modified by the filmmakers – it’s a glorious example of why independent low budget invention and resourcefulness so often trumps big budget studio fare.

IN A VIOLENT NATURE

Writer-director Chris Nash’s almost art-house reworking of the slasher movie formula kept flipping back and forth between my A and B lists, but in the end it lodged so deeply in a dark corner of my brain that I just couldn’t demote it.

For those familiar with the slasher subgenre, the storyline of In a Violent Nature will offer no surprises. A group of teenagers camping in the Canadian woods come across a ruined shack, on which hangs a golden locket that one of them takes and pockets. This act of desecration awakes the previously dead and buried body of a monstrous killer named Johnny, who was facially disfigured in a past act of violence and who subsequently dons a mask and starts murdering the teenagers one by one. I’ll bet you’ve never heard that one before.

What differentiates this film from (almost) every past entry in this much-maligned subgenre is Nash’s approach, which aside from a campfire scene to introduce the teenagers who are soon to become slasher fodder, sticks almost exclusively with Johnny as he slowly and silently stalks his prey without a note of musical accompaniment. And Nash is in no hurry here, patiently following Johnny as steadily trudges through the woodland undergrowth with smoothly executed Steadicam shots, in the process creating a work with the feel of a Friday 13th knock-off directed by Elephant and Last Days era Gus van Sant. I completely get why the film has been dismissed by a fair few genre fans, despite the extreme goriness of a couple of the kills, but I was darkly mesmerised and appropriately disturbed by Nash’s approach, and I’m not sure I’ll ever watch a regular slasher film again without recalling the alternative viewpoint that this movie forces its audience to take.

There’s an excellent analysis of what makes In a Violent Nature stand out from the crowd (as well and highlighting where it momentarily stumbles) titled The Ambient Horror of In a Violent Nature over on the In/Frame/Out YouTube channel, though newcomers to the film should be aware that it contains a whole stream of spoilers: https://youtu.be/-CrYfQpnXAg?si=rqIeKzWsfcpD7yfw.

INFINITY POOL

|

With his marriage on rocky grounds, writer James Foster and his wife Em are on holiday in a gated resort in the fictional country of Li Tolqa. While there, James is approached by the attractive Gabi, who claims to be a fan on the only novel that he has so far published. She invites him and Em to dine with her and her husband Alban that evening, and the following day, the four go for a drive in the local countryside, despite being expressly forbidden from leaving the resort, stopping off to sunbath and drink, during which things covertly hot up between James and Gabi. On their way back to the resort that night, the inebriated James is at the wheel of their car and accidentally hits and kills a local man. The next day he is arrested and informed that the penalty in Li Tolqa for such a crime is death at the hands of the firstborn son of the victim. The police reveal, however, that there is an unusual process reserved for foreign nationals available for a considerable fee, in which the offender is cloned and the duplicate is executed in his place.

Writer-director Brandon Cronenberg is no stranger to making outlandish scientific concepts seem disturbingly plausible, from the monetisation of celebrity diseases in Antiviral to the ability to inhabit the body of another in order to get close to protected people in order to assassinate them in Possessor. Infinity Pool may occasionally wear its social subtext on its sleeve, but it really comes into its own with the bizarre process used to clone the increasingly beleaguered James and the troubling philosophical questions that further cloning raises about the true nature of identity and the self. Alexander Skarsgård is on fine form as the increasingly beleaguered and frightened James, but it’s Mia Goth who steals the show as Gabi, sensually seductive in her first dealings with James but genuinely terrifying when his luck takes a seriously downward turn – the moment when she simply barks out his name as an elongated command when he refuses to leave a bus on which he is attempting to flee is one of scariest sounds to worm its way into my ears all year.

KNEECAP

|

The story of the formation and rise to notoriety and fame of the Belfast-based Irish rap trio of the title, co-written by two of the group in conjunction with the director, with the rappers playing themselves on screen. It sound like the recipe for a self-indulgent disaster, but in the hands of sophomore feature director Rich Peppiatt, and the talented trio of Liam Óg, Naoise Ó Cairealláin and JJ Ó Dochartaigh (aka Mo Chara, Móglaí Bap and DJ Próvai) leading the cast, Kneecap doesn’t just buck the musical self-portrait trend, it’s an absolute riot from its opening frames and one of the sharpest and most enjoyable films of 2024. Self-described as a “mostly true story,” it chronicles the formation of the first Irish language rap band at a time when the language was in danger of being erased from existence and speaking it was seen was political act. As a result, Kneecap’s insistence on rapping exclusively in Irish courted instant controversy, while their sideline activity as enterprising drug dealers made them the target of threats from the paramilitary group, Radical Republicans Against Drugs.

I know I’m echoing what so many others have said before me, but I went into this knowing little about Kneecap and completely unaware that the band members were playing themselves, and even when I discovered that Liam and Naoise were the real deal, I remained convinced that JJ was being played by an experienced and talented actor who was finally getting the big break that he deserved. All three are naturals, but Próvai takes it to another level, even holding his own in a cast that includes Michael Fassbinder as Mo’s on-the-run paramilitary father, Arló Ó Cairealláin. Employing a whole range of always wittily employed stylistic tricks, including hand-written translation of the Irish dialogue and lyrics and a comically trippy stop-motion animation sequence, but this is always put to inventive use and never feels gimmicky. Peppiatt does take a few cues from Danny Boyle’s Trainspotting (1996) and Justin Kerrigan’s Human Traffic (1999), but Kneecap still stands proudly on its own considerable merits, thanks to the specifics of its locational, political and social setting, its vibrant cast, its thunderous energy, its sometimes uproarious humour, and Kneecap’s infectious take-no-prisoners music.

THE LAST OF US

|

For years, we videogame players have groaned our way through a string of woeful attempts to turn successful games into movies, and despite the considerable influence that each of these mediums have had on the other, the experience of watching a film is very different to the participatory nature of videogames. This explains why it’s easier to make a videogame from a film, as you’re adding interactivity to an essentially passive experience, but make a film from a game and you have to strip it of the very aspect that made it a success in the first place. That said, where movies almost always trump games is in the depth of their storytelling and characters, but while for decades game characters were little more than a collection of anonymous sprites, recent developments in motion capture technology have allowed for a far more realistic and movie-like level of performance. Even with that in mind, the stories driving videogames tend to be either threadbare or divorced from reality, their prime purpose being to move the player from one tense or exciting encounter to the next. There have been a few notable exceptions, but the game that really turned the tide on this score was Naughty Dog’s 2013 emotionally charged survival-horror action-adventure masterpiece, The Last of Us. It’s a beloved game with a compelling linear story and a subtle belter of an ending, and the news that it was being adapted as a TV mini-series had my gaming friends and I all rehearsing what we fully expected would be another series of disappointed groans. Oh , how wrong we were.

The first positive sign was that the series was being funded by HBO, which at least had a track record of producing quality shows. Our ears pricked up further at the news that the game’s writer and co-director, Neil Druckmann, would also be writing the show in collaboration with Chernobyl screenwriter Craig Mazin, and that both would be directing individual episodes. Then the first trailer dropped and it was immediately evident that the makers had at least captured something of the essence what made the game such in involving experience. Only when the series finally hit the screens did the full weight of what Druckmann, Mazin and their collaborators had achieved, recreating the look, the tone and the narrative of the videogame, but expanding on a range of elements and storyline beats to create a fully cinematic experience and one of the tensest, most gripping and convincingly performed post-apocalyptic survival horrors to yet hit the screen. For many, the series hit an emotional high in episode 3, a bottle episode titled Long, Long Time that was only vaguely hinted at in the game and written specifically for the series, a story that had viewers posting videos online of themselves in floods of tears while watching its deeply poignant conclusion. It’s a sign of the times that the high viewer rating that the episode had on various sites was then review-bombed by bigoted right-wing dickwads because the relationship at the episode’s centre was between two lonely men. Season 2 is dropping soon, the trailer for which has got us all fired up, though anyone who has played The Last of Us, Part 2 will be waiting with nervously clenched teeth for what will doubtless one of the toughest scenes to sit through all year.

FALLOUT

|

In light of the above, the question that many of us were asking was whether the success, acclaim for, and care taken with the game-to-series adaption of The Last of Us would prove to be a one-off or a sign of more positive things come. We didn’t have to wait too long for an answer, which came in the Amazon funded series based on Bethesda’s buggy but much-loved post-apocalyptic Fallout game series. We knew from the off that things would have to be different here, as where The Last of Us had a compelling and emotionally resonant storyline, the narratives of the Fallout games – at least from Fallout 3 onwards – tend to be secondary to the encounter-peppered open worlds in which they were set. Complicating matters further, in the Fallout games you don’t play a pre-crafted character but one of your own making, and the manner in which the narrative unfolds tends to be shaped by individual player choice. It usually takes me an age to finish the main story of any Fallout game (and despite over 300 hours of play, I’ve yet to get around to completing Fallout 4) because exploring the creature and settlement peppered wasteland is always more fun.

So how do you go about making a series based on such games and also make the show accessible to people who have never played Fallout in any of its forms without pissing off the games’ substantial fanbase? First up, the makers took a cue from The Last of Us by producing the show in conjunction with Bethesda Game Studios and Bethesda Softworks and bringing the company’s head honcho Todd Howard on board as an executive producer. Then they handed the project to a team of talented writers under the guidance of executive story editor Chaz Hawkins and series creators and screenwriters Graham Wagner and Geneva Robertson-Dworet. They hired directors and designers who completely understand the games and their appeal, and who were clearly determined to go to great lengths to physically recreate the in-game world, right down to its costumes and props, and rather than adapt one of the existing game stories, the screenwriters opted to create a new one that respected the lore and settings and technology of the source material instead.

In the opening scene of the first episode of the resulting series, the sudden escalation from international tension to all-out nuclear war that triggers the main story is presented from the viewpoint of young Janey Howard and her former cowboy movie star father Cooper Howard and brilliantly handled. We’re then transported 219 years into a future, where luckier survivors are living in secure vaults deep beneath the ground, enclosed communities whose younger inhabitants have never seen the sun. Among them is Lucy, the teenage daughter of vault 33 overseer Hank McLean, and when a deal struck with a neighbouring vault for Lucy to marry one of their young men ends in carnage and the kidnapping of Hank, his determined daughter heads out into the wasteland to find him. This effectively begins Lucy’s open world adventure, one that that unfolds in tandem with that of Brotherhood of Steel squire Maximus and brings Lucy into conflict with Cooper Howard, who has long since mutated into a gun-toting Ghoul.

For Fallout game fans and newcomers alike, Fallout is an absolute delight, capturing the spirit of the games and recreating its environments and technology with astonishing accuracy whilst liberally lacing its hugely engaging story with black humour, wonderfully offbeat characters, and gleefully over-the-top violence. London-born Ella Purnell is a joy as Lucy, a ball of wide-eyed innocence whose upbeat “okey-dokey” lends a comical edge to even the grimmest of tasks, and she’s perfectly matched by (and later teamed with) Aaron Moten as Maximus, who masquerades as a Brotherhood of Steel knight after the one he was serving is killed. It’s great to see Kyle MacLachlan beaming his winning smile as Hank MacLean, but stealing just about every scene he appears in is Walton Goggins as The Ghoul, a facially disfigured bounty hunter with a mean shooting hand and a contempt for just about every living thing, the most glorious creation in a consistently inventive series. Visually and aurally captivating, with a top-notch supporting cast, it was described rather wonderfully by Brian Tallerico at RogerEbert.com thus: “Imagine Lynch’s golly-gee, picket fence America from something like Blue Velvet mixed with Mad Max: Fury Road.” That works for me.

LATE NIGHT WITH THE DEVIL

In 1977, audience numbers for the sixth season of late night TV variety talk show Night Owls are on the decline. A year after the tragic death of his actress wife Madeleine, long-time host Jack Delroy is hoping to bump up the ratings with a live show on Halloween night built featuring a young girl named Lilly D'Abo, the sole survivor of a Satanic church mass suicide and whom author and parapsychologist June Ross-Mitchell claims is able to summon a demon. Also on the show are flamboyant psychic Christou, musician Cleo James, and James Randi-like former magician turned professional sceptic Carmichael Haig, who wearily exposes the tricks behind all of Christou’s mystical readings and scoffs at the very notion that anything Lilly does is evidence of demonic possession. But as the show progresses, the signs are that maybe, just maybe, Haig’s cynicism may be blinding him to a potentially deadly truth.

The third film listed here that successfully emulates the look and feel of a format and technical process from past years (four if you count the TV show extracts from I Saw the TV Glow), with sibling directors Cameron and Colin Cairnes creating the look and feel of a late 1970s TV talk show by successfully emulating its content and visual style, with the film playing out largely in real time as the show unfolds as if we are watching the live broadcast that it purports to be. This intermittently switches to what the film claims is behind-the-scenes footage shot of the show’s production, and while this does occasionally record conversations that I can’t believe a real-life Delroy would have allowed to be filmed (or at least conducted without acknowledging the close-quarters presence of the camera), it never breaks the flow and provides crucial details that help ramp up the tension in the later stages. The actors are all absolutely on-point, with David Dastmalchian (who has a key supporting role in another film on this list) bumped up from character actor to lead player here and absolutely holding his own as Delroy, a man still haunted by the death of his wife but desperate to recapture his former TV glory. Fayssal Bazzi hits just the right note as showman psychic Christou, and Ian Bliss nails Haig’s impatient scepticism, in the process becoming a most effectively disruptive presence, exposing Christou’s fakery and repeatedly frustrating Delroy’s attempts to tease out the demonic encounter that the studio audience is presumably eager to see. But my favourite performance comes from Ingrid Torelli as Lilly, who manages to transform smiling politeness into a clear indication that something is just not right with this innocent-looking girl. If the film has a precedent, it’s the rightly celebrated BBC docudrama Ghost Watch, but Late Night with the Devil still carves its own rightful place in horror movie history, and its enthusiastic fans include a certain horror author named Stephen King.

LONGLEGS

|

Despatched as one of several teams to knock on doors as part of an investigation into recent serial killings, introspective FBI agent Lee Harker and her newly assigned partner pull up on an average suburban street, where Harker instinctively identifies the house in which she believes the killer is hiding. Her partner is scornful of what he dismisses as a groundless hunch, but when he approaches the front door of the property he is shot dead, leaving the seriously rattled Lee to apprehend the man responsible. Curious about her ability to so quickly identify the location of the killer, Harker’s supervisor, Agent William Carter, has her tested for psychic abilities, an exam that she achieves an unusually high score on. As a result, she is assigned to the case of Longlegs, the self-signed nickname of the prime suspect in a string of violent murder-suicides involving families, her task being to decipher the symbols and codes used by the killer on letters left at each of the crime scenes.

The third horror-themed feature from director Osgood Perkins – the eldest son of actor Anthony Perkins – is easily his best yet, an utterly gripping and deeply unsettling serial killer story whose machine-tooled execution is matched by a string of nicely understated performances, and one whose excesses are deliberately crafted and put to most effective use. I watched this knowing little about it beyond the positive buzz that it was generating, and it had me enthralled from its opening prologue, where a young girl encounters a supremely creepy individual whose identity is partially obscured by disorienting manner in which he is framed. Once Harker and her partner reach their assigned neighbourhood, it’s once again the filmmaking that had me compelled, with cinematographer Andrés Arochi Tinajero blending tellingly framed static camera with silky smooth Steadicam follow shots, the 2.39:1 aspect ratio used repeatedly used to isolate Harker within the expanse of the scope frame in an expressionistic representation of her solitude and outsider status.

It Follows lead player Maika Monroe is quietly impressive as the emotionally buttoned-down Harker, Blair Underwood exercises similar control as Carter, and Alicia Witt is excellent as Lee’s religious mother, Ruth. The performance that could and indeed should have thrown this otherwise low-key ensemble off balance is the one delivered by Nicolas Cage as Longlegs, who almost overplays the “hello little girl” creepiness and at one explodes in a rage of demented in-car fury, but somehow, Perkins shapes this into an increasingly disquieting counterpoint to the unhurried precision of Harker’s investigation. This also has me fired up for the director’s upcoming Stephen King adaptation, The Monkey, a film in which he also appears to have a substantial supporting role.

MARCEL THE SHELL WITH SHOES ON

After separating from his wife, cash-strapped documentary filmmaker Dean moves into an Airbnb, where he discovers that the house is already home to a small talking, single-eyed and two-footed shell named Marcel who has lived there for some time with his ageing grandmother Connie. Dean convinces Marcel to allow him to document his daily life on video, and when he starts uploading clips to YouTube, Marcel quickly finds himself becoming a national celebrity.

A first feature mockumentary by Dean Fleischer Camp – who effectively plays himself in the film (though remains largely off camera) – acts as both a prequel and a sequel to his Marcel the Shell short film trilogy, which was written by Fleischer Camp and his then wife, actress Jenny Slate, who is the entrancingly child-like voice of Marcel in both the shorts and this feature. In a life imitating art twist, Slate and Fleischer Camp separated at an early stage in the film’s seven year production process, but they remained committed to what Slater has claimed was a favourite film project for both of them. And oh, does that labour of true love come across in bewitching spades. There’s a touchingly affecting innocence to Marcel’s worldview, and the ingenious ways he has found to navigate the house (stomping in syrup to climb up walls is a personal favourite) never failed to put a wide smile on my face, while his devotion to his wise old grandmother stirred memories in me that brought a walloping great lump to my throat when Connie’s health begins to fade and she puts a brave face on it for her grandson’s sake. Oh, I’m getting all teary just thinking about it.

Technically, the film is a testament to modern-day digital compositing and Fleischer Camp’s imagination and skill as an animator and filmmaker, with the animated Marcel blended with live action so invisibly – including on very mobile handheld shots – that I spent the entire film believing completely that he was the real deal. The voice acting by Slate as Marcel and Isabella Rossellini and Connie is sublime, and the resulting film is an alternately tender, witty, humorous, surprising, warm-hearted, sad, and gloriously uplifting tale that appears to have had the ability to connect with and move viewers of all ages, even old moany buggers like me.

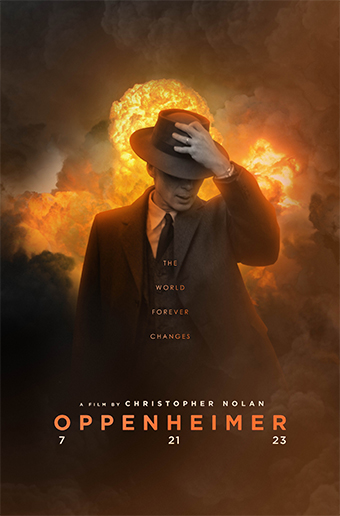

OPPENHEIMER

|

The second half of what became known as the Barbenheimer phenomenon (I’m amazed how quickly that term was added to the dictionary in Microsoft Word) is the one that theoretically had the smaller chance of setting the box-office alight, being a three-hour movie about the man regarded as the father of the atomic bomb, the absolute flipside of Barbie’s cheery dayglow satire. Yet research suggests that to date it’s made $1 billion against its $100 million budget. It’s also a film I took some time to getting round to seeing, partly because of the subject (for obvious reasons, the film was not exactly warmly greeted in Japan, a country for which I have a very personal affinity), partly because it was directed by Christopher Nolan, some of whose films I’ve admired more than I’ve enjoyed (and I have enjoyed them, just not as much as others clearly have). I needn’t have worried, as for my money Oppenheimer may just be Nolan’s finest achievement to date, a work of magisterial breadth and scope that transforms what is in essence a personal story into an historical saga. Particularly impressive is manner in which the film flips liberally between timelines to tell an essentially linear story without ever becoming confusing or messy, a triumph of planning, scripting and editing for a film that benefits no end from an excellent cast on impeccable form, with Cillian Murphy hitting a career high (so far, at least) as the driven and ultimately tortured Robert Oppenheimer. It had the best and most expansive sound design this side of Civil War, and like Oliver Stone’s JFK (1991) before it – a film that Oppenheimer occasionally reminded me of – the density of its storytelling fully justifies that three-hour running time.

Film review [Camus] >>

PAST LIVES

In a South Korea suburb, childhood friends Na Young and Hae Sung share a strong bond and even speculate that they will one day get married, but their friendship suffers a serious blow when Na Young’s family emigrates to Canada. As the years pass, the lives of these two individuals follow very different paths, and while they initially lose touch, the rise of the internet enables them to reconnect via video chat until Na Young, who has changed her name to the more western Nora, asks for a break to concentrate on the writing that has become her vocation. To this end, she attends a writer's retreat, at which she meets and falls in love with Caucasian Jew, Arthur Zaturansky. 12 years later, Hae Sung and Nora finally arrange to meet up in New York, both now unsure how their how they will feel about each other after so long and so many changes to their respective lives.

It's a simple concept, but is handled with extraordinary tenderness, humanity and emotional honesty by Canadian first time feature director Celine Song. Breaking down exactly why this one so affected me is something I find oddly hard to quantify, but the fact that it featured so highly on so many other 2023 favourite films lists confirms that I’m not alone in my response. At its heart are three pitch-perfect performances by Greta Lee as Nora, Teo Yoo as Hae Sung, and John Magaro as Arthur, who kicks against movie expectations by understanding and accepting Nora’s long-standing bond with Hae Sung and being an easily likeable and supportive husband. This puts the audience in the challenging position of wanting to see Nora get together with Hae Sung whilst simultaneously not wanting her happy marriage to the kind-hearted Arthur suffer in the process. I was captivated by this film, and – SPOILER ALERT! – Lee’s brilliant, heartbreaking, and oh-so-real portrayal of someone fighting tears and a deep-felt longing whilst trying to maintain an expression of upbeat positivity in the film’s final scene had me mysteriously leaking water from my eyes.

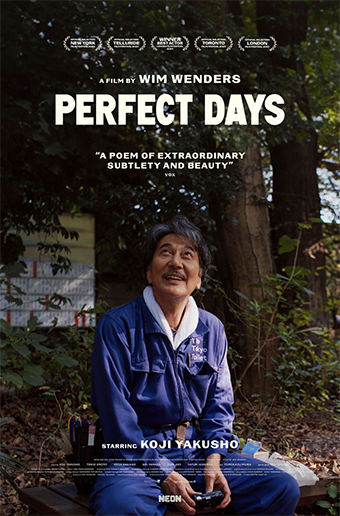

PERFECT DAYS

|

It still feels odd that one of the most quintessentially Japanese films I saw in 2024 was directed by a 78-year-old German. Of course, the filmmaker in question is none other than Wim Wenders, who has made his mark repeatedly on world cinema with films such as Alice in the Cities (Alice in den Städten,1974), Kings of the Road (Im Lauf der Zeit, 1976), The American Friend (Der amerikanische Freund, 1977), and the utterly gorgeous Wings of Desire (Der Himmel über Berlin, 1987). Although his early work told primarily German stories, Wenders later branched out with his documentary Lightning Over Water (1980) about then ailing American director Nicholas Ray, his widely acclaimed adaptation of Sam Shepheard’s Paris, Texas (1984), and most relevant to this film, his two Japan-based documentaries, Tōkyō-Ga (1985) and Notebook on Cities and Clothes (Aufzeichnungen zu Kleidern und Städten, (1989). The earlier film especially communicated Wenders’ fascination for Japan and his almost empathic connection to the Japanese way of life, something that that is written all over every scene in Perfect Days.

The film does not tell a traditional story, but instead documents the quiet, almost ritualistic daily life of solitary middle-aged Hirayama, who cleans public toilets in the Tōkyō district of Shibuya for a living. A lowly profession this must sound, but in Japan even a humble task would be carried out with a thoroughness and dedication that many would not even apply to their own home (seriously, Japan is the cleanest country I have ever visited by a country mile). After completing his ablutions and watering his plants, Hirayama greets each morning with an optimistic smile and a can of coffee from the vending machine behind his van. Every lunchtime visits he the Yoyogi Hachiman shrine, where he sits and eats his sandwiches while gazing the movement of the trees in the wind, which he photographs on the pocket film camera he carries with him at all times for this purpose. This may sound somewhat humdrum, but the film’s gentle tone, coupled with Wenders’ observational documentary approach, Toni Froschhammer’s deftly economical editing, and a gorgeously restrained and naturalistic performance by veteran actor Yakusho Kōji – he of Shall We Dance? (1996), The Eel (Unagi, 1997), and Cure (1997) to name but three of many – make for oddly compelling and genuinely restful viewing.

Hirayama’s job also takes us on a whistle-stop tour of some of Tōkyō’s more intriguingly designed public conveniences (including the ones with see-though glass walls that turn instantly opaque when you lock the door), and paints a seductive picture of a humble man who is at complete peace with himself, his work, and his surroundings. During the course of the film this is disrupted by the girlfriend-chasing antics of his brash and seemingly self-centred young co-worker Takashi, but this leads to an unexpected generational transfer of musical appreciation (there are some great but always diegetic needle drops here, including one the title should lead you to expect), and Takashi himself is later revealed to have a cheerfully kind and non-judgemental side to his personality that puts an appreciative smile on Hirayama’s face. The arrival of his teenage niece Niko for an unannounced visit sees him open up a little in a way that suggests a kinship with his niece that he just does not have with her wealthy mother, to whom he admits he hasn’t spoken for several years. This is another film that casts a spell on the watcher that cannot easily be conveyed by the written word, a work that made me want to shed my own life of its considerable clutter and live more simply and is, without question, the most rewardingly and relaxingly zen film experience I had all year.

POOR THINGS

Having followed his films since our film society screened Dogtooth, I’ll eagerly seek out anything by Greek filmmaker Yorgos Lanthimos, and will also watch just about anything featuring actors Willem Dafoe or Emma Stone, which for me made Poor Things a must-see as soon as I first read about it. That said, having never read the Alasdair Gray novel that this is a somewhat loose adaptation of, even Lanthimos’s previous work left me ill-prepared for what unfolded.

The film is set initially in Victorian London, where we are introduced to former suicide victim Bella and unorthodox and facially scarred surgeon Godwin Baxter, who effectively brought Bella back to life by transplanting the still living brain of the baby she was carrying into her adult body, and is now raising her as his adopted daughter. Taking up the post of Baxter’s assistant is medical student Max McCandles, who is tasked with documenting the currently still infantile Bella’s gradual development, a sometimes colourful task that takes an embarrassing turn for Max when Bella embarrassingly discovers the pleasures of masturbation. By this point, the morally upright Max has already fallen for Bella and asks Baxter for her hand in marriage, but her new-found interest in the pleasures of the flesh, coupled with her rapidly advancing intelligence and desire to see more of the world is taken advantage of by Baxter’s pompous lawyer Duncan Wedderburn. To Max’s dismay, Duncan whisks the willing Bella off on an intercontinental tour, during which of Bella’s almost insatiable desire for sexual gratification is matched by her continuing intellectual development and independently-minded quest for enlightenment.

No plot description could convey what makes this film look and feel like no other I can easily recall, with the world presented almost exclusively as it is seen through Bella’s eyes, a colourful, distorted and surreal picture-book representation of the real world which occasionally reminded me of the airborne city of Columbia in the Bioshock: Infinite videogame. At first it seems clear that Bella is being exploited, treated by the Frankenstein-like Baxter as a scientific experiment to be studied, and by Duncan as a willing outlet for his sexual cravings, with only Max seemingly concerned for her best interests. As Bella’s brain develops and her curiosity and thirst for knowledge sees her self-confidence increase, however, roles are gradually reversed, with Bella developing as an adult as the increasingly frustrated Baxter becomes more infantile.

Poor Things is an almost overwhelming rich cornucopia of offbeat storytelling, fascinating character development (Bella’s refusal to self-censor leads to some uproarious exchanges), and eye-popping photography (Robbie Ryan) and production design (Shona Heath and James Price). Ultimately, however, it’s the performances that sell it, notably Emma Stone’s brave and brilliant portrayal of the gradually evolving Bella, although Mark Ruffalo is a riot as the self-important English lawyer Duncan Wedderburn.

REALITY

On 3 June 2017, FBI agents arrived at the home of American US Air Force veteran and NSA translator Reality Winner to interview her and conduct a search of her home as part of an investigation into the leak of classified information that has been mailed anonymously to the news organisation, The Intercept. She was subsequently arrested and charged with removing classified material from a government facility and mailing it to a news outlet and was sentenced to 63 months in prison under the 1917 Espionage Act, the longest ever prison term for such a charge. (For the record, Donald Trump was recently also prosecuted under the same act for removing boxes of top secret and classified documents and storing them in the bathroom at his Mar-a-Lago, and basically got off scot-free for this far more serious transgression.)

Given the parameters set by writer-director Tina Satter and a co-screenwriter James Paul Dallas, Reality shouldn’t really work. Taking its cue from Satter’s Verbatim Theatre stage play, on which this film is based, the FBI’s arrival at Reality’s house and the subsequent search and questioning is recreated in real time, with all of the dialogue drawn exclusively from the transcripts of the recordings made by the agents themselves. On paper, this should make for a moderately interesting but dramatically dry experience, but in the hands of Satter and her collaborators, it proves anything but.

Key to why Reality quickly becomes such gripping and intermittently tense viewing is down as much to the consistently excellent performances of a completely convincing cast as to Satter’s probing camera and Nathan Micay’s almost ambient but stress-inducing score. Sidney Sweeney in particular is terrific as Reality, superbly conveying the sense of being caught in a lie that you’re still hoping against all hope that you can wriggle out of, but I’ll also give props to Josh Hamilton as Agent Garrick, whose faux-friendly, small talk-led approach provides an insight into how suspects can be coerced into incriminating themselves. Satter even comes up with a novel but effective way of visually representing the redacted elements of the audio recordings. Bold, important and excellent cinema.

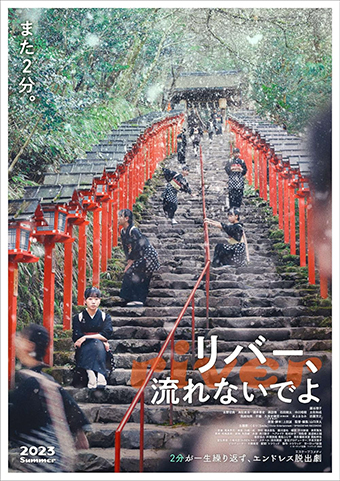

RIVER [RIBĀ, NAGARENAIDE YO]

|

Having landed with a bang with the conceptually and structurally inventive microbudget gem Beyond the Infinite Two Minutes (Dorosute no hate de bokura, 2020), director Yamaguchi Junta and screenwriter Ueda Makoto revisit and rethink the time-loop concept of their debut for a work that is even more imaginative and structurally complex than its predecessor, and for my money even more fun. At a small but long-established ryokan in Kibune in Kyōto, waitress Mikoto stands by the river that runs alongside the establishment, seemingly lost in thought. She quickly snaps out of it and returns to her duties, which involve helping the head waiter to clear one of the rooms previously occupied by now departed guests. Two minutes into the task she finds herself standing back by the river, and when she enters the ryokan as before, both she and the head waiter have a strong sensation of déjà-vu. Then, two minutes later, Mikoto is back by the riverside again, and everyone in the ryokan and the restaurant opposite begin to realise that they are caught in a mysterious time loop from which they seem unable to escape.

Imagine the repetition of Groundhog Day occurring every 120 seconds and affecting everyone in the district instead of just one individual, and at a location just isolated enough to make it impossible to reach the nearest town before the time loop resets itself and returns everyone to their original locations. It’s a really neat template for a brilliantly constructed narrative in which the characters quickly come to terms with their situation and start planning what they will collectively do when the next reset occurs in the hope of working out what has caused the temporal disruption and ascertain how far it may have spread. Great fun is had with the reaction of the staff and guests: the distraught kitchen worker who is unable to finish heating a requested flask of sake to drinking temperature; the half-naked man in the wash room who cannot rinse the soap from his hair and keeps ending up back in the bath; the author struggling to meet a deadline whose work keeps deleting itself but who is then delighted by the realisation that the deadline in question has now been indefinitely postponed; the two cheerfully partying friends who are blissfully unaware that time is repeating and simply delight that the bowls of rice they are hungrily consuming keep refilling themselves.

The watertight structure and complexity of Ueda Makoto’s twisty, multi-character screenplay is a dizzying miracle of careful planning that has several personal stories developing in tandem, which later expand to include a bemused local hunter and Mikoto’s boyfriend, who was initially unaware of the situation because he was taking a nap. Crucially, there’s never a moment where I became remotely confused or lost track of the various character threads, which is a real tribute to Makoto’s writing and Yamaguchi’s direction. It’s also a technically impressive achievement, with each time loop covered in a single two-minute handheld take that often concludes on a shot of Mikoto that is then perfectly match-cut to the one of her standing by the river at the start of the time loop that immediately follows. The continuity of the weather does vary wildly, the result of shooting on location over several days in which one day’s heavy snowfall had melted by the next, which is casually explained away with a single line of dialogue – whether you buy this or not, it matters little when stood against how sublimely everything else works. It’s a lovely little film with a satisfying and heart-warmingly do-it-yourself, low-tech finale that had me beaming, and is a testament to just what can be achieved on a tiny budget with a lorryload of ingenuity and talent.

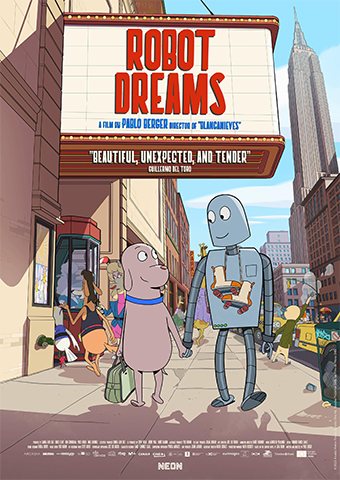

ROBOT DREAMS

|

Pablo Berger’s Robot Dreams is another of those movies that wasn’t on my watchlist until I was eventually prodded into hunting it out by the positive words of others, and oh am I so glad I did. With an old-school artwork style drawn from the graphic novel by Sara Varon on which the film is based, the film is set in a world populated entirely by anthropomorphic animals and centred around Dog, a canine who lives a solitary life in a small Manhattan apartment. Fed up with being alone, he responds to a TV advertisement and orders a humanoid Robot, and once it is assembled and activated, the two immediately hit it off and become the closest of friends. Being new to the world, Robot’s wonder at even the smallest aspects of his surroundings proves infectious, prompting Dog to see more of the city and awakening him to the beauty of things he had previously taken for granted. Then, after a particularly enjoyable day at the beach during which the two swim happily in the sea, the sunbathing Robot finds he is unable to move, and is just too heavy for Dog to lift unaided. The defeated Dog sadly heads home for the night, but the following morning heads back to the beach with some tools to help his friend, only to find that the beach has been closed for the winter and that he is strictly forbidden from entering.

All of this makes for beguiling viewing, but this is just the setup for the emotional rollercoaster ride that follows, one that repeatedly had me fighting back tears, as much out of recognition of the experienced truth of situations as for my empathy for characters that felt as real to me as any three-dimensional humans. With the two friends forcibly separated, the film develops into a study of loneliness, separation, broken relationships and how we move on from them. This is most poignantly captured by the titular dreams that Robot experiences whilst lying immobile in the sand, the first couple of which we effectively misdirected into thinking are real, and which later take a cruel turn when group of possible rescuers turns out to be anything but. There’s a magical sequence involving a nesting bird, and one that really hit home for me involving unreturned girlfriend calls, but I still wasn’t prepared for the massive emotional wallop delivered by the bittersweet finale. It’s gorgeous work whose complete lack of dialogue (the animals make noises, but do not otherwise speak) gives it true international appeal, and I never thought I’d see the day when I’d be championing September by Earth, Wind & Fire as the perfect musical representation of friendship and love. I’ll end with a nod to critic Robbie Collin in his Telegraph review,where he summed up the near universal but generationally differing appeal and emotional impact of the film with the line, “kids will be amused and enchanted, and any accompanying grown-ups existentially destroyed.” Oh, he’s not wrong there.

THE SUBSTANCE

Former celebrity Elisabeth Sparkle’s star is fading, and on her 50th birthday she is unexpectedly dumped from the popular aerobics TV show she has hosted for years by sleazy producer Harvey. When her distress and anger causes her to crash her car, she ends up at the hospital, where a nurse covertly hands her a flash drive containing a commercial for The Substance, an off-the-books serum that promises to unleash a younger version of its user. Elisabeth opts to give this black market drug a try, but it comes with very specific instructions that must be followed to the letter, and once Elisabeth gives grisly birth to the younger Sue, she has just seven days before she must return to her 50-year-old self, a cycle that she is warned will have serious consequences if broken.

The second feature from Revenge director Coralie Fargeat is a hyper-stylised satire on the shallow nature of celebrity, the male gaze, the commercially driven obsession with a specific notion of female youth and beauty, and how this impacts on the self-image of an individual working in an industry in which it is a principal currency, all of which is dressed up in the clothing of a Cronenbergian body-horror. Stanislas Reydellet’s expressionistic production design, with its dayglo colours, large flat surfaces and gargantuan rooms, work together with the extreme wides, smooth dolly shots, overly intimate close-ups and saturated lighting of Benjamin Kračun’s scope cinematography to create a world slightly out of kilter with our own, as if being viewed through the eyes of beauty consultants and drug-fuelled architectural minimalists. When the body horror elements kick in, they do not hold back, and even remotely squeamish viewers would be advised to proceed with considerable caution, as every time I thought that the film had gone as far as it could go on this front, it then went further. This eventually takes it into thematically dark and claustrophobically disturbing territory, and a nightmarish layer of hell from which I couldn’t see Elisabeth and Sue – who are, you have to keep reminding yourself, essentially two sides of the same individual – ever escaping. A superb, perhaps career best performance from Demi Moore as Elisabeth is given a run for its money by Margaret Qualley as Sue, and there’s a scene-stealing turn from Dennis Quaid as the ever-smiling, overly ebullient producer Harvey, whose shrimp eating close-ups have been cited by Demi Moore as the film’s scariest scene.

As a side note, there’s an excellent video essay on the role of neo-expressionism in the film by Thomas Flight, which you can find here: https://youtu.be/IvZGrF1hSbY?si=AT1WIieDxWasOQPS

THE ZONE OF INTEREST

Having landed with a splash (small film in-joke there) with his electrifying debut, Sexy Beast, former music video and commercials director Jonathan Glazer has continued to impress with films that are unique in their tone and approach, a quality that’s written on every frame of his first feature since the mesmerising 2013 Under the Skin, loosely adapted by Glazer himself from the novel by Martin Amis. Although there is a whisper of an overarching narrative, the film is essentially a portrait of SS officer Rudolf Höss in 1943, as he and his wife Hedwig and their five children make a life for themselves in a large house with a generous garden that is located next door to the Auschwitz death camp, of which Höss was commandant.

Probably the most genuinely and hauntingly chilling film I saw all year, Glazer’s steely observational approach, all static scope compositions and smoothly executed dolly shots, is another film that on paper could seem worthy but uninvolving, but it nonetheless exercises a steely grip that you almost want to shake off. While the cinematic flipside of the handheld, academy framed urgency of László Nemes’ devastating Son of Saul (Saul fia, 2015), it nonetheless shares that film’s decision not to show the unfolding horrors but to grimly infer them through the soundtrack instead. Where Son of Saul placed us inside Auschwitz just metres from where unspeakable acts were being committed, the sounds we hear in the The Zone of Interest are a little more distant and yet somehow every bit as disturbing, in part because they play out over images of a family going about its daily business and receiving guests as if the house was located in an isolated spot in the country, its residents seemingly obvious to the unspeakable acts taking place just over the nearby wall.

A strong performance by Christian Friedel as Rudolf Höss is matched all the way by another excellent and committed turn from Sandra Hüller as his wife Hedwig, but to say more about how the film plays out would be redundant for work that needs to be experienced rather than described in any detail. The cumulative effect is genuinely and appropriately disturbing, all the more so at time when the world’s richest man is cosying up to and openly promoting a far-right party as the only hope for a modern Germany. Now where have we heard that one before?

Well, that’s it for last year, and the year before, and I still have a few films from both years to catch up on before moving on to whatever 2025 has to offer. Thank you all for your continued support, and take care of yourselves and each other in these increasingly troubled times. Right, back to the disc reviews at last!

<< Page 1: The B List

|