|

In may seem a little odd to start comparing legendary Japanese filmmaker Imamura Shôhei to perennially cheerful Blues Brothers and An American Werewolf in London director John Landis, but there's a sequence about ten minutes into Imamura's Palme D'Or winning 1997 Unagi [The Eel] that can't help but recall a similar one from Landis's undervalued 1985 Into the Night, particularly as it occurs at almost exactly the same point in both films. In Landis's movie, office worker Ed Okin comes home early one day, peers in through his bedroom window and sees his wife having sex with another man. In Imamura's film, office worker Yamashita Takuro comes home early from his nightly fishing trip, peers in through his bedroom window and, well, you can guess the rest. But there's a key difference here. Ed had no idea of his wife's infidelity and is caught completely on the hop, whereas Takuro had been tipped off by an anonymous letter, and it's right after this that the two films starkly diverge. Whereas in Landis's film, the sex is heard rather than seen and the focus instead is Ed's crestfallen reaction, in Imamura's, the sex is not only shown but enthusiastically performed and punishingly lingered on, which has the effect of aligning us with Takuro's humiliation and sense of betrayal. And while Ed walks away with an air of dazed defeat, Takuro takes a knife, walks into the bedroom and angrily stabs his wife to death. A short while later, in a sequence that feels both surrealistic and quintessentially Japanese, he walks into a police station, covered in enough blood to suggest he was standing two feet from an exploding buffalo, hands over the murder weapon and formally turns himself in.

Eight years later (we can only speculate at the reasons for this seemingly short sentence), Takuro is released on a two year probation and relocates to a quiet rural area where only his locally based parole officer – the Reverend Nakajima – is aware of his past sins. Here he buys an abandoned canal-side shop and puts a skill he learned in prison to use by setting himself up as a barber, but remains socially distanced from the community he serves. His only companion is an eel that he kept as an unofficial pet during his time in the clink, an animal with which he appears to be able to telepathically communicate.

OK, a little clarification is required here. Takuro is no Japanese Dr. Doolittle, nor does he possess a supernatural connection with freshwater fish. This is more a psychological connection, his experiences having left him withdrawn enough to ensure that the eel has become the one creature he feels able to open up to. Questioned on it by Nakajima, Takuro tells him simply, "he listens to what I have to say."

One day, Takuro is fishing for eel food when he discovers the body of a young woman lying in the reeds by the canal, a would-be suicide named Keiko who with medical help makes a full recovery. Regretting her actions, she later visits Takuro to personally thank him for saving her life. Looking to put her own troubled past behind her, she moves in with Nakajima and his wife Misako, who asks Takuro if he would be willing to employ her at his shop. Troubled by Keiko's physical resemblance to his late wife Emiko, Takuro is initially reluctant, but soon finds himself working well with his new assistant. But his slow rehabilitation and potential future with Keiko is threatened when the truth about his past risks being exposed.

If the story revolved around that last paragraph alone then we'd be on very familiar ground – tales of mutually attracted individuals who run into problems on the road to contentment have been two-a-penny since cinema's earliest days. Even the main location – a barbershop that doubles as a communal hub – has since become a familiar American movie locale. But, of course, it's not quite that simple. From an early stage, Imamura presents Takuro in a sympathetic light, a quiet and politely apologetic figure who has been left damaged by his past deeds and his time behind bars. And yet almost the first thing we watch him do is stab his wife to death, a selfish and extreme response triggered by his own wounded pride, and just a few minutes of screen time later – his prison term passes in a flash – we're asked to engage with him on an empathic level. That this proves so disarmingly easy to do and that we remain subsequently untroubled by his earlier crime is probably a ripe subject for an in-depth psychoanalytical essay.

What unfolds is a portrait of Takuro's slow social adjustment and his developing friendship with the small band of misfits who gravitate to his shop, an upbeat bunch consisting of grizzle-faced fisherman Takada, quiff-haired would-be playboy Yuji and young construction worker Masaki, who spends his time building an eye-catching beacon to attract the attention of passing UFOs. This engaging background detail keeps the tone a lot lighter than Takuro's emotional journey might lead you to expect, with all three hangers-on reflecting aspects of Takuro's personality that he has yet to come to terms with, something highlighted by a brief conversation with Masaki about his UFO fixation: "Aren't you really just afraid of making friends with people?" Takuro asks him, to which Masaki responds, "Just like you, eh?"

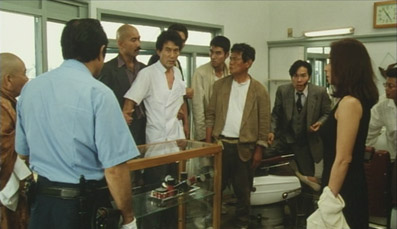

Keiko quickly proves an asset to the shop and the regulars begin openly speculating about the nature of her relationship with her self-conscious employer. Complications arise in the form of poison pen letters to Takuro, the arrival of Keiko's mentally unstable mother, and an ex-con named Tamasaki who threatens to reveal all about Takuro's past. Just how and indeed if Takuro will resolve his inner conflict becomes the real focus of the film – Keiko is clearly attracted to him, and in spite of his determination to keep her at a distance he seems to like her, but the past repeatedly threatens to cloud the picture. At one point, Takuro firmly asks Keiko to leave while in the process sharpening a razor for the following day's work and I momentarily feared for her immediate safety. And when she starts preparing bento lunches in the manner of Takuro's late wife, the idea that history might be starting to repeat itself becomes a real concern. It all comes to a head with the arrival of Keiko's criminal ex-lover Dojima and two of his cronies, demanding the return of money that Keiko has taken in her mother's name. This climaxes in an extended brawl involving just about everyone, one whose playground scrappiness transforms a theoretically serious scene into a small comic delight.

That Unagi won Imamura his second Palme D'Or is, in retrospect, a little surprising. For all its many virtues, it's neither as dynamic nor as adventurous as a good many of the director's previous films. It does share several of their underlying themes, albeit in toned-down form, from the focus on social outsiders to the symbolic role played by animals and the frank and unglamorous presentation of sex, elements that were given fuller head in the earlier Profound Desires of the Gods and The Ballad of Narayama (Imamura's first Palme D'Or winner). Here, the metaphoric function of Takuro's pet eel should be evident to any alert viewer (an animal with phallic qualities living a life of social isolation that will only be freed when its owner's issues are resolved, one way or another), and the film's two sexual encounters both have clear narrative purpose. The focus on one person and his offbeat entourage inevitably results in a reduced sense of scale when compared to the ensemble work in the above mentioned films and even earlier features like Pigs and Battleships or Stolen Desire, and we never get as discomfortingly close to our troubled lead character as we did with serial killer Enokizu Iwao in the director's 1979 Vengeance is Mine.

But Unagi is still a fascinating, tightly structured and deftly observed study of loneliness, redemption and gradual healing, one that in spite of the early violence remains one of Imamura's most accessible and enjoyable films. Takuro's eel tank hallucinations aside (one of which briefly echoes a memorable sequence from the previous year's Trainspotting), the handling is resolutely low-key, the largely immobile camera quietly observing Takuro predominantly in wide and mid-shots and rarely in close-up, the traditional cinematic route to character connection. The film is also well cast and engagingly performed. I have a particular soft spot for veteran actor Satô Makoto's turn as the grizzled Takada and the young boy who practically bellows his appreciation at being given a potato snack, and showing commendable restraint as Takuro is Yakusho Kôji, a now busy performer who really came to prominence in the late 1990s with lead roles in films such as Shall We Dansu? and Kurosawa Kiyoshi's mesmerising Cure.

Unagi will always have a special place in my heart for being the film that belatedly introduced me to the cinema of Imamura Shôhei. Since then, many more of Imamura's films have been made available in the UK through Eureka's Masters of Cinema label and I'm now in a better position to judge the film in relation to the director's previous work. That so many of the earlier films now feel even more exciting and innovative is perhaps unsurprising – Imamura was 70 when he made Unagi – but this is still an entrancing work that shines quietly its performances, its storytelling, its extraordinary opening sequence, and – in its belief that no-one should be denied the possibility of redemption – its gentle humanity. Just spare a thought for Emiko, who although the catalyst for the story, died a violent and unjustified death at her husband's hands for nothing more sinister than having the hots for another man.

Okay. On the plus side this is a very clean print with a reasonable level of detail and contrast that is pleasing enough when outside in the sunlight, which is also where the colour rendition is at its best. So it's largely good news, then? Not quite. There is an earthier tone to the interior and night scenes, and when the light level drops, the contrast flattens out a little and blacks turn to grey. A bigger issue is that, somewhat surprisingly for a DVD released in 2012, this is a letterboxed 1.73:1 transfer in a 4:3 frame and slightly windowboxed at the sides. It has also been standards converted from an NTSC original, albeit with no obvious issues. The good news is that the English subtitles have been positioned within the picture area, enabling you to utilise the zoom mode on your widescreen TV. Not-so-good is that doing so really emphasises the picture softness, particularly when compared to an even half-decent anamorphic transfer.

The Dolby 2.0 mono Japanese track is clean and clear, a little narrow in the dynamic range at times but reproducing the dialogue and Ikebe Shinichirô's music rather well. The English subtitles are optional and localised to UK English.

Not a thing.

Well it's great to see Unagi out on UK DVD, but with Masters of Cinema currently doing such a sterling job on the filmmaker's back-catalogue, the non-anamorphic transfer and lack of extra features make this disc look a little like the runt of the litter. Thus while the film comes highly recommended, it's hard to quite as enthusiastic for the DVD, though the New Yorker US DVD release features what looks like the very same transfer, making this the only option at the moment for those wishing to own the film.

The Japanese convention of surname first has been used for all Japanese names in this review.

|