|

A best of 2012 list and we're already two weeks into 2013?

I might be late to the party, but isn't it even more ridiculous that the party sometimes starts as early as November? People publish these lists, writing off the last four or five weeks of the year for no discernable reason. Yet it was during the twelve days of Christmas feasting and film-watching, that thanks to iTunes downloads and region A Blu-rays, I saw the worst film of the year (Sleepwalk with Me) and two that made my top ten list (Higher Ground and The Turin Horse). Discounting December is a bizarre practice I'll always fail to understand, giving the writer no real time for reflection in the rush to announce their selection along with everyone else.

Of course no list can ever truly be concrete as our opinions and responses to films are in a constant state of flux, but I at least wanted enough time to really take stock of hundreds of titles and make mine as considered and solid as possible. US critic Jonathan Rosenbaum is dead on in his assertion that lists of this kind tend to favour recent discoveries and in the case of those two last-minute top ten entries, I felt it was necessary to let them percolate a while before ranking them. The Turin Horse was a gut reaction, instant placement in the ten that felt more and more like the right move a fortnight later, whereas Higher Ground worked its way steadily up from the number twenty spot to number ten, a decision confirmed by a second viewing. Knocking Cosmopolis out of the top ten was indeed a very tough decision and one that ultimately came down to the feeling that though I absolutely love it, a second viewing will determine just how much. And while you won't find a bigger fan of Paul Thomas Anderson, The Master finds itself just outside the top ten at number seventeen. On first watch it's a psychologically rich but emotionally cold film that despite its seductive, trance-like storytelling, still found me longing for the day when PTA still made films about people rather than ideas.

With more films now than ever before, every year, the dung pile flung off the Hollywood conveyer belt gets bigger and bigger, quantity far outweighing quality. While I'm not sure we can ever again experience the '95, '99 and '00 vintages of not so long ago, 2012 was certainly a year in which the vanguard did some of their best work, bold original voices were heard, and stories were told from intriguingly fresh perspectives. Take for instance the subject of disability, so often a manipulative ploy to wring tears out of Oscar voters, this year we were gifted with two brazenly honest and empowering accounts of characters overcoming stigma and discrimination in mainstream society. Ordinarily, films of this type "celebrate" characters working with or conquering the difference that supposedly defines them. Both Rust and Bone and The Sessions see past the handicaps, focusing on the common humanity of their characters, rather than letting their frustrations of not being able-bodied take sole focus. If the subject of disabled people having sex is one of the last great societal taboos, then both of these films tackled the issue head-on in their own distinct way, proudly declaring our equal right to be recognised as sexual beings.

As a point of comparison, 2011 certainly had a much stronger top ten than this year, with two of my picks scoring perfect tens and the rest all nines. This year I awarded only one IMDB rating of ten (Killer Joe), a couple of nines and the rest eights, but throughout the new year that may very well change as I catch-up on at least fifty titles that time didn't permit me to see. Notable omissions include The Hobbit and Life of Pi (I wanted to avoid the Christmas crush) and a trio of well regarded art-house films, I wanted to see but wasn't quite as willing to pay art house prices for; Corpo Celeste, Hadewijch and 7 Days in Havana.

2012 ought to be remembered if for no other reason, as one of the most remarkable years on record for female performances. Much has been said in the trades about female power players recently paving the way for progress which still has a ways to go, as the number of women behind the camera remains depressingly disproportionate. Though when it came time for their close-up, in front of the camera the starlets were out in force, all with challenging roles to match. Many of these I'm about to get in to, suffice it to say that in previous years where the best actress categories seemed padded out and you might struggle to come up with even five truly memorable turns, this year I saw at least twenty.

Be it established talent restored to former glories (Parker Posey, Price Check, Gina Gershon, Killer Joe), familiar faces pushing themselves into new places (Ludivine Sagnier, Love Crime, Eva Green, Dark Shadows), up and comers cementing their one-to-watch status (Brit Marling, The Sound of my Voice) or startling fresh faces both young (Marie Féret, Mozart's Sister) and old (Emmanuelle Riva, Amour), there really was an incredible range and so much to be hopeful for in terms of great female roles, going into 2013. For those interested in statistics, Christina Hendricks is the only actress to appear in two films on this list, John Hawkes the only actor.

My complete ranked and rated list of 2012 releases can be found here. As usual I go by a mix of UK and US release dates, given that the bulk of my Blu-rays are region A and that I tend to use the US iTunes store over its UK equivalent. The US store is inarguably becoming the only (legal) way of seeing so many of the indie releases that never make it to our shores, now that digital rentals are going online the same day as their limited theatrical releases in key markets like New York and Los Angeles. How else would I have have caught up with Amigo, John Sayles' latest attack on the arrogance of American imperialism,

or actor Todd Lousio's second turn in the director's chair, Hello, I Must Be Going? So if certain titles on the complete list fail to ring any bells or are completely unfamiliar, there's a good chance they were rented through the US iTunes store.

And with that, my top 10 of 2012 is as follows:

2012 saw many films act as warnings about the dangers of cult indoctrination, and while The Master, Martha Marcy May Marlene, The Sound of My Voice and Electrick Children, are all excellent and right up there with the year's best, Higher Ground is all the more remarkable as an admirably restrained, evenly balanced story of one woman's lifelong struggle with faith, with no insidiousness implications whatsoever towards its congregation of fundamentalist born again-Christians.

After her family is beset by tragedy, young Corinne Walker's search for surer footing sees her budding intellectual curiosity get the better of her, as she enters into an uneasy relationship with God and joins a religious commune. The patriarchy of this community might seem regressively deplorable in the way it stifles the voices of its "womenfolk" – especially as the story is all about Corinne's attempts to understand herself, be understood and find her own voice – but we're quickly reminded that one man's misogyny is another woman's order.

Indeed, the film takes great pains to acknowledge that in living their lives a certain way, these are good people; kind and loving to one another, and choosing to express that love through God. As Corinne tries to understand what that commitment means and make it clear and real to herself, the film's quiet tragedy is her growing recognition that after playing pretend for the last thirty years, she can do so no longer. Lacking any sense of self-respect and having made a habit of relying on others has led Corinne into making a terrible decision that's unconsciously taken her years to come to terms with. In both her direction and lead performance, Vera Farmiga shows us just how hard it is is to take the higher ground, admit your mistakes, call it quits and walk away. The scene is which a cast out Corinne faces her congregation and speaks plainly of what she's learned about herself during the time spent with them, is the equal of any Oscar reel clip you'll see in February. Next to her schoolyard showdown with Kate Beckinsale in Nothing But the Truth, this is possibly the single best scene of Farmiga's career thus far.

Ordinarily, Hollywood only tends to make two types of film about the Christian faith, either exclusively for Christians, or films that parody them. Higher Ground being that rare exception that doesn't define its characters by their zealous beliefs and to this end, Farmiga is careful to stress the point that it is Corinne who is at fault here, not the religion to which she so desperately wants to belong.

Vera Farmiga has long one of my favourite actresses, a firebrand performer of flinty ferocity, always making bold decisions in her choice of material, so it's especially heartening that her directorial debut is as good as it is and that her choice to get behind the camera has no detrimental effects on a typically disarming and devastating lead performance. Her achievement here is all the more impressive for being five months pregnant while shooting, taking on a period movie that spans thirty years for her debut and gambling on her little sister Taissa to play her younger self, a then untested actor who has since gone on to a prominent part in TV's American Horror Story.

There's no sense of ego here either. As an actor-director she is generous with a brilliant cast of established players and soon to be bigger names, including John Hawkes, Nina Arianda and Donna Murphy. These are performances all with lives of their own that aren't stuck in the orbit of their star. Farmiga, unlike many actors-turned-directors a little too in love with their own close-ups, knows when to call cut and hand it over to others. Preaching it like she means it, you don't have to be of the faith or a churchgoer for Farmiga to make you a believer.

Over the course of five days, nature rages out of control as the end of the world draws near. With nothing to obstruct it and no escaping it, the human race is being put to rights by a bone dry cloud of dust, ravening the already barren, autumnal landscapes of the remote countryside.

In accordance with the perceived wisdom of animals sensing danger before humans, the horse of the title has already resigned himself to fate, flatly refusing to leave his stable. As the father and daughter to whom he belongs continue to wearily endure, we witness both the estimable humility and grinding hardship of the simple life.

Forced inside by the hurricane outside their door, the Chekhovian drudgery of their final days is a truly mesmeric endurance test of cinema. The rangy two and a half hour run time is made up of ritualized acts of silent obedience, and repetitious routine, exactingly played out in long takes from all angles. The film's oppressive mood batters and lashes like the wind outside, the blustery black and white photography a blend of Victorian gothic and archival photos of depression era breadlines. If the mood is one of misery and misfortune, the maddening musical motif of composer Mihály Vig (who'd I mistaken for Philip Glass the entire time I was watching) plays these emotions on a loop, turning the film into an echo chamber of austerity. In this sombre serenade there's an unspoken plea for mercy and redemption at the hands of God, even as father and daughter openly acknowledge that after destroying the earth, mankind has likely been deserted by any such entity, and that theirs is an existence with neither God nor Gods.

Alongside The Impossible, The Turin Horse is the year's most reluctant disaster film and in both cases you come away with an appreciation of the physical hell the actors must have gone through in making it. Working with wind machines on full blast all day no doubt proved it's own special torment, making the hopelessness of the characters that much easier to access. The end result is a countdown to extinction far more memorable for its biblical sense of the end being neigh than any excessive amount of pixelated destructo-porn. With his swan song, Béla Tarr goes out with a bang that never comes and a sense of unease that lingers long afterward.

With our review of Antiviral, and interview with Brandon Cronenberg (son of David) still to come in February, it's enough to say that the film stands apart as one of the most visually terrifying and thematically rewarding debuts in years. Even more startling, vibrant and imaginative than the people's indie champion Beasts of the Southern Wild, I still can't fathom why more eminent critics didn't make a similar fuss when the film bowed at last year's London Film Festival. Somehow managing to fly completely under the radar, it'll no doubt soon find its way onto every "best dystopia" list of the future and is sure to develop a rabid cult following over the next couple of years.

An inventively insane vision of a frighteningly foreseeable future, Cronenberg junior depicts a world in which people are infected with celebrity aliments to feel closer to their favourite stars. A queasily needle-prone, blood soaked satire on the vampiric nature of celebrity fanaticism, the more unsettlingly surreal it becomes, the more convincingly inevitable this future world seems.

Depraved, diabolical and delirious, Cronenberg junior is well on par with the old man, from whom he's so clearly inherited the obsessional techno-flesh gene. As if in the thrall of a virus himself when he made it, the young director pushes the conceptual design elements of his distubia beyond the limits of perversity, not so much warping minds as warning them to remain vigilant against the controlling, evil alchemy of corporate medecine and technology.

I saw the Palm D'or-winning Amour the same day as Antiviral, and never expected the first time director to out-shock Haneke.

Click here to read full review and watch an interview with director Brandon Cronenberg.

The Tsunami-sized backlash has already begun, but for all the accusations of manipulative whitewashing and overly sentimental filmmaking, I stand firm by the film's inclusion here. A behemoth of event cinema the likes of which we haven't seen in the last fifteen years, the size and scale of this thing is beyond belief. It's perhaps effective as it is due to the sense of every creative decision, every single frame, being the result of multiple departments working in perfect accord towards the same singular vision. With so much money being thrown around, bureaucracy is often the undoing of a blockbuster's artistic aspirations, and that makes this film something of a rarity.

Read the full review here.

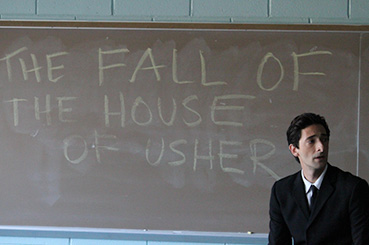

A carrion call to a crumbling education system, Tony Kaye's blistering return to narrative cinema after the behind the scenes bad blood of American History X and a sojourn in documentary land, somehow manages to pack even more emotional wallop than his debut.

Through the eyes of supply teacher Henry Barthes, we see the front lines of a war which teachers are steadily losing, as both sides take heavy casualties. Stripped of authority, respect and the power to restore order in the classroom, a starry staffroom of despairing, disenchanted teachers (Christina Hendricks, Lucy Liu, James Cann and Bryan Cranston) wonder at what point their students ceased to be learners.

In the performance of his career, Adrien Broody is the inspirational teacher struggling to inspire, straightjacketed by a system that only understands the laws of grade point average, completely disregarding passionate teaching of the syllabus. Condemned to care in an inner city blackboard hell, Barthes broods like a better-dressed Travis Bickle, sensing that he too is starting to becoming desensitized.

Seventies comparisons abound in every aspect of the film's volatile temperament and central performance; Barthes' attempts to turn around the lives of a wayward student and teenage street whore (Betty Kaye and Sami Gayle, both making deep impressions in their screen debuts) are fraught with the same frustration and hopelessness that charged other seventies greats Pacino and Hackman in era-defining work.

187 and Half Nelson aside, these days the genre is mostly known for its montage heavy wish fulfilment that all but insults your intelligence. If we were to believe the multiplex, the only way to understand and appreciate literary classics is to find suitable points of reference with hip-hop.

Coming from an altogether edgier bygone era of scrappy furiousness, Detachment drags the genre kicking and screaming back to a time before the likes of Dangerous Minds and Coolio.

Rich in symbolism and subtext, it’s not at all by accident that the August 6th 1945 same-day-birth of Ginger and Rosa in London is match cut to the mushroom cloud of Hiroshima. Exploding girls shaped by nuclear nightmares, years later as teens, the girls find themselves growing up in the shadow of the Cuban Missile Crisis, a manifest sexual metaphor for the volatility of adolescence.

In Ginger & Rosa, destructive force intended for entire populations is metered out on a lifelong friendship which internalises the bomb before being destroyed by it. While many critics might have scoffed at such on-the-nose warnings, you can't expect subtly from an atom bomb.

A pair of luminous performances set the high stakes of this relationship not long before it gives way to atomic growing pains. Despite being only fourteen years old, Elle Fanning is already the "actress of her generation", a heavy plaudit she wears well, in a role that cements her transition from child actress to adult thesp. The star of Somewhere, Twixt and Super 8 is already something of a screen veteran at this point, yet her experience does nothing to show up Alice Englert (daughter of director Jane Campion) in her debut role. Englert is so scarily self-assured and sexually liberated, she was seemingly born to burn up the lens. Credit to both performers, so free and easy with one another that you have no trouble believing Ginger and Rosa have been best friends all their lives.

Blowing free and doing everything together (even their first sexual encounters are shared), the girls live for today, knowing tomorrow they may die. Music, fashion, sex and under age drinking distract from thoughts of mutually assured destruction, and as they hitch rides fuelled by positive pop music, there's a rhythm of always-on-the-run youthful exuberance, often found wanting in Walter Salles' recent adaptation of On the Road.

They keep on growing as they keep on moving, and growing apart as they grow older. Representing opposing ends of the era's radicalism, Ginger is a Simone de Beauvoir–reading existentialist led to activism and protesting the bomb, while Rosa thinks of nobody but herself, her sexual self-destruction a bi-product of the age. If Rosa's empty fixation on her crucifix gives her divine right to go after everything she wants but never had, then hopping into bed with strangers is something of a religious quest to find a father figure before it's too late.

Watching her disturbed bestie stroke her crucifix like rosary beads, Ginger takes an identical cross (given to her by Rosa) and mimics the action, trying and failing to understand the friend she's steadily losing. Their separation is accelerated by the growing attraction between Ginger's charismatic horndog father Roland (a superb Alessandro Nivola) and Rosa, now quickly blossoming into womanhood. Mentally mature beyond her years, but still with the unmistakable girlish squeal of early adolescence, Ginger not only feels betrayed but left behind. Turning her back to the camera as Little Richard's 'Tutti Fruitti' plays on the Wurlitzer, is one particularly poignant moment in which Ginger says goodbye to the childhood she's yet to outgrow.

Adulthood hardly seems much to aspire to, many of the authority figures here squabbling like children. Sally Potter's script has been heavily criticised for giving outspoken academic Roland some terrible pseudo-philosophical-political claptrap to spout, but surely that's the point? Such pompous, flowery rhetoric could only be taken seriously by the kind of young, impressionable girls Roland's trying to bed. And so it is with Rosa.

A freethinking word twister who can't abide bourgeoisie death-traps like monogamy and the word 'dad', Roland's phoney modernity is nothing more than a licence to be randy. Similarly, his self-righteous disgust with the "shoulds and the oughts of so-called family life" is a jail card dodge of his parental responsibilities, making the the understatement of the year when he admits he's not father material. Yet, Roland's way with words is such that it's easy to see why women are drawn to him. Formally imprisoned as a contentious objector, the way in which he speaks of the experience gives us a glimpse of the humanity beneath the horniness. "Confinement can be utterly beautiful if it's only a choice. A prison cell is the ugliest expression of minimalism."

All this sordid family dysfunction eventually builds to a confrontation that would make Jerry Springer quake in his boots. As Ginger's increasingly frenzied fears of the world's end start to dominate her conversation, it becomes clear that it's nuclear family not annihilation, which is the cause of her distress.

The synchronicity between the nuanced script, the transparent performances and the visual context in which we find them, draws out many telling emotional details (less successful at period perhaps) and Potter streamlines these complexities to make her most distinguished yet commercial film to date. It may have gotten buried at the arthouse, opening against Beasts of the Southern Wild the same week in October, but this is one film that really deserved consideration as the token British hopeful for this year's academy awards. Like the similarly fated Hyde Park on Hudson, Potter and Fanning's award chances blew over as early festival buzz quickly dissipated. Still yet to be released in the States until mid-March, it simply didn't have a big enough international profile at the time for a successful Oscar campaign. The Americans will soon get their first look (albeit it in limited release) and before that, here in the UK, we get to give it a much deserved second chance as it's released this week on Blu-ray and DVD by Artificial Eye. We will update this review with the Blu-ray details when our copy arrives.

Click here to watch an interview with director Sally Potter and lead players Elle Fanning and Alice Englert.

Flitting nimbly between confectionary comedies and dark dramas, François Ozon is too busy playing with and subverting genre conventions to ever risk being labelled an auteur. His latest film goes so far as to constantly query its intended audience and in provoking these questions without necessarily providing answers, the fanciful Frenchman has made his first bona fide masterpiece. Oozing hilarious, barbed satire, it's a picture that mocks and delights in the indiscrete charmlessness of the bourgeoisie.

An atom bomb of verse metaphor and manipulation is dropped into the house of a jaded creative writing professor Germain (Fabrice Luchini, perfect as a past his prime teacher in both dress and disposition) who becomes obsessed with the riveting dialogue and exciting scenarios imagined by model student Claude (Ernst Umhauer). Everyday after school, Claude goes home with a fellow student to a working class household with tacky middle class aspirations and uses these visits as material for his assignments. Germain is captivated by this mocking peephole which permits him to see how the other class lives, and it's not long before he's taking these stories home and reading them to his pretentious wife Jeanne (Kristin Scott Thomas, in her best French-speaking role yet), the owner of shock art gallery 'The Minotaur's Labyrinth' whose current show "The Dictatorship of Sex" looks like your average porn shop.

Like her husband, Jeanne is soon taking pleasure in guiltily laughing at them and we at her. Within these layers of voyeurism, Claude parodies his readers (and viewers) as much as the characters he's writing about.

As a satire of clueless class misconception, Claude writes the Artole family as the most suspect stereotypes and still, the professor with an inflated sense of his own academic prowess fails to notice how the family's behaviour is cartoonishly American. The gym teacher father who dresses like a US high school coach talks of "hitting the shower", makes six-shooter gestures with his fingers, is forever ordering pizza and devotes himself to basketball. It's an impossibly unrealistic caricature with too many absurd twists to be taken seriously, yet German and Jeanne's fevered voyeurism is such that it too is indulged, with a knowing Bernard Herrmann pastiche courtesy of composer Philippe Rombi.

Real or not, these domestic misadventures are a reawakening for the one time author, wanting to teach his student about life and a way of viewing the world through improved literary technique. Spending more and more time with one another, Germain begins to see Claude as his vicarious ticket to the big time. Needling editorially to the point of co-authorship, Germain wants Claude to be published and succeed where he did not. Much of their talk about the particulars of the art of writing are cleverly complimented by the meta-narrative staging; having teacher and student walking inside, around and commenting upon the story they're creating as we watch various drafts being acted out. Furthermore, it's a film that benefits from being subtitled in unexpected ways. "Reading" the film, you get the feel of line beats and paragraph breaks, just as if you'd picked it up as a book.

A commentary on how and why we tell stories, and who we tell them for, in Ozon's strangely dextrous and dense career, this is top tier stuff. Undoubtedly his best film yet.

Detailing the sexual and emotional needs of the severely disabled in a frank but sensitive manner, The Sessions is an inspirational and deeply resonant film, especially for the physically disadvantaged, deserving a big screen love story that reflects their experience. The story of polio-afflicted poet Mark O'Brien, who lived in an iron lung for thirty-some years before hiring a "sex surrogate" to experience physical intimacy and the pleasure of intercourse for the first time, is sure to resonate in the hearts of many disabled people with a desire for romantic relations. So much more than a hopeless disabled person’s schmaltzy quest to get laid, The Sessions is a compassionate character study of a man in whom a seldom-considered audience will be able to recognize themselves on screen. The sessions themselves are fraught with frustration and embarrassment, and the empathy of such moments where the struggle of simply removing a shirt is dwelled upon, has much to do with director Ben Lewin being a survivor of polio himself. Steering well clear of beautifully crafted movie sex, everything under the sheets feels true to life, impromptu and more than a little ridiculous. Detaching itself from its own tactile eroticism, the film boldly explores the psychological implications of touch and the dangers of transference in such a context. Ordinarily, sex scenes only account for a single point of view, but Lewin's camera spends equal time on each face, registering the intensity of their time together on both parties. You might be left sobbing, but thanks to two physically precise, all-on-display performances from John Hawkes and Helen Hunt, this is so much more than O’Brien’s sob story.

Read the full review and see our interviews with the film's lead actors and producer here.

Acclaimed playwright and troubled filmmaker Kenneth Lonergan's second big screen foray in twelve years is an incredibly sharp and powerful look at ideas of justice, blame, loss of innocence and responsibility. Addressing extremely heavy subject matter with unerring psychological accuracy, this piercing character exploration does no less than assassinate the character of the profoundly dislikeable teen at its centre.

Simultaneously hateable and sympathetic, Lonergan leaves no stone unturned in his dissection of all Margaret's insecurities, contradictions and foibles. Causing a terrible bus accident and withholding vital information from the police before attempting to set things right long after the fact, the hyperbolic, self-aggrandizing adolescent soon finds herself forced out of a shell of Upper East Side privilege, her guilt, exacerbated by the still raw wounds of post 9-11 cityscape. It turns out that the world has much bigger problems and frankly no time to listen to hers.

Neither will her desperately single mother; throwing herself into rehearsals of her latest Broadway play as she attempts to forget what a mess she's made of her home life. When Margaret talks to her estranged father on the telephone, he doesn't want to hear about what his daughter's going through, only what he thinks she ought to be doing with her life as he makes empty promises of the quality time they'll spend together on a vacation that'll never happen.

And so the bull-headed blithe spirit goes elsewhere for a shoulder to cry on, unwelcomingly crashing into the lives of the bus driver's she ruined and her high school maths teacher with whom she has an affair, tussling uncertainly with questions of right and wrong as she swings back and forth like a hormonal wrecking ball.

A sprawling cast of reputable names (Mark Ruffalo, Matt Damon, Jean Reno, Kieran Culkin) befits scenes set at the Metropolitan Opera, where the abundantly verbose film hits a sublimely unspoken emotional climax. Lonergan leaves no character behind, taking time to build the interior life of each, all as complicated and as contradictory as Margret herself, not just another foil for her alienation and apathy to bounce off. Lonergan even finds time to grandiloquently pontificate on how judiciary frameworks all too often obstruficate the truth, even as Margaret's mass of conflicting impulses exerts an insistent gravitational pull.

In a banner year for female performances, Anna Paquin's is the very best of them and there can be no superlative too purple for what she does here. Immature and aggressively flirtatious, yet possessed of a wisdom beyond her years with something close to second sight, Margaret is a character unchained from the tidy rules of screenwriting. Her flip-flopping emotions aren't manipulated by plot but drive it entirely, a cherishable reminder that characters can hold more than one position at the same time and can be for something whilst also against it. It's largely thanks to Paquin's riveting performance that the finally released film lived up to and exceeded my expectations of the twelve year wait since Lonergan's last, You Can Count On Me, co-incidentally my favourite film of all time. Where Margaret will fall on my all time list deserves at least a few years yet, but for now I'll go ahead and call it an acerbically analytical near masterpiece.

The trailer park meets Greek tragedy next, in a film that shows an ugly side of human nature so grotesque you have to laugh. If Bug, William Friedkin's last collaboration with playwright Tracy Letts made audiences' skin crawl, Killer Joe is sure to make them wretch. Such is the sickening degree of one hillbilly brood's filial cannibalism, as a son plots to kill his mother with the help of his father, before stealing the insurance money bequeathed to his mentally disabled sister in order to pay off a sizeable debt to loan sharks threatening to kill him.

This isn't a crime of passion, just basic instinct and the Smith family is as basic as they come. It makes them that much more contemptible that father and son talk about their plot openly and without pause, yet are too chicken shit to do anything themselves. Enter Joe Cooper, a corrupt county sheriff who moonlights as a paid assassin. Unable to front Joe's fee, Dottie is then offered as a retainer and the family's fate is bound to the hit man. Even more ruthless and astronomically more intelligent than the lot of them put together, Joe has the drop on these Texan dumbfucks the moment we first hear the clink-clunking of his cowboy boots coming round the corner.

All this pre-mediated scheming might be off-putting were it not for the fact that every member of the Smith clan is staggeringly stupid. Emile Hirsch as Chris, the 'brains' of the outfit, hasn't any awareness of his own stupidity either, so it makes his eventual comeuppance as he tries to cut corners and outsmart Joe all the more satisfying. It's also very, very funny. The scene where Thomas Haden Church's father, Ansel goes to meet with a lawyer, all done up in a cheap suit, offers the biggest laugh of any film I saw in 2012. Trying to neaten him up before the meeting, Ansel's new girlfriend Sharla pulls on a loose thread and the whole arm falls off, yet they continue talking as if nothing's happened. A hilarious insight into character and where these people come from, the cut of the coat couldn't be better suited to the cloth.

The characters' moral vacuity belies the film's tonal complexity, Friedkin and Letts contorting genre with the same diseased logic as its eponymous killer. As a twisted fairy tale in which Joe is a prince of darkness come to "rescue" Dottie from the frying pan only to cast her into the fire, Matthew McConaughey's performance is eerily reminiscent of Robert Mitchum in Night of the Hunter. Putting away the washboard abs and trading rom-com smarm for stone-faced manipulation, McConaughey's untrustworthy eyes and voice of evil lend chills to Joe's warped idea of right and wrong. Joe is much talked about in hushed tones long before he appears and McConaughey comfortably fills the boots of memorable, menacing advisory.

Juno Temple is almost as creepy as the childlike Dottie, whose mother tried to suffocate her with a pillow and suffered brain damage as a result. We're never sure of Dottie's real age (which makes the leathery advances of much older Joe extremely uncomfortable to watch) or how fully aware she is of her part as a pawn in this plot. When Dottie appears to accept Chris' not-so-ambiguous incestual urges toward her without disgust, we don't know if this is innocence corrupted or the art of seduction as a means of escape.

Gina Gershon in a welcome return to the big screen as Sharla, reminds us what an uncompromising actress she is and how comfortable she was with the nudity Showgirls, bearing all in the first few minutes. The bawdy beaver shot sets up the pulpy trashiness of this larger than life film in which rain only ever lashes and dogs continually howl. Again there's something of a fairy tale element here, with American gothic production design shot like film noir. When we first see the family trailer from the outside on a dark and stormy night, it's like stumbling upon Dracula's castle or the House on Telegraph Hill.

This year has seen Gershon playing two deceitful, redneck vamps to perfection in both this and straight-to-video release Breathless, but it's Joe that asks her to do something even more demeaning than share the screen with Elizabeth Berkly. A family dinner-from-hell showstopper has her perform fellatio on a chicken drumstick held at crotch level. Make-up smeared Sharla goes down on that thing as if her life depends on it (it does) and Gershon understands that from a performance standpoint, betting the farm is the only way to make the scene play. An indelible moment that no number of cold showers can scrub from the mind's eye, it's one for which the film is already infamous, but that Gershon can live down (unlike Chloe Sevigny giving Vincent Gallow an actual blowjob on screen, y'know for art), because her fearless commitment to an act such public humiliation draws equal attention to the shame of the family sitting ideally by as much as the act itself.

Though it could also be argued that this is the moment in which Ansel grows his first brain cell. Realizing that Sharla has played him even more so than his son, he knows the best thing he do at this point is look after number one and stay out of it. As he leans back, cracks a beer and enjoys some deep fried revenge, Church lets this dim bulb shine brighter than any of them for one brief, blackly comic moment.

Completely character driven, perversely scripted, tinged with gothic-noir stylings and lots of Juno Temple nudity, if that's what you're after, Killer Joe has so much going for it. Most of all, there's the insatiable appeal of films about really nasty, reprehensible people doing even nastier, reprehensible things to people just like them - and doing them unthinkingly with such ease. Aside from Neil LaBute and Todd Solondz, there aren't many like Letts who write domestic depravity that's so whip smart and in this way, Killer Joe ticks a lot of personal boxes. |