|

Dethroning or even remotely challenging self-proclaimed "king of the world" James Cameron (king of the Hollywood blockbusters, we'll give him that) was never going to be easy, as very few filmmakers are ever afforded the opportunity to work at a similar scale and budget with teeming departments of crafts people in the hundreds under their command. Spielberg aside, Cameron faces precious little competition in the exalted rank of tent pole auteurs making no-expense-spared, grandiose, exhaustive epics with headline-grabbing budgets and the entire toy box of directorial tools at their disposal.

Enter Spanish helmer J.A. Bayona, whose foreign–language hit The Orphanage trumpeted his considerable talents but gave no such indication he could so assuredly mount a setpiece heavy, effects laden juggernaut and play the Hollywood big boys at their own game.

The powerful story of one family's survival of the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami, was prepped for almost two years and shot over twenty-five weeks across more than sixty sets between Spain and Thailand. In the course of that time and just one film, Bayona has made the seemingly impossible leap from small-budget genre filmmaker to A-list mega budget visionary.

My own experience of seeing the film couldn't have been more ideal. Distributor Entertainment One treated us to a screening at Dolby's own preview theatre, so the sound was optimized with startling precision and maximum volume*. Still, nothing could have prepared the assembled audience of critics for the hell unleashed by sound designer Marc Orts, who should already be making space for Oscar on the mantelpiece.

If you're lucky enough to catch this in a cinema screen with state of the art sound (and really, I insist you make the effort), the opening half minute of black screen accompanied by the foundation-shaking rumble of an approaching wall of water surging through the darkness, startlingly match cut to the engine roar of an overhead plane shuttling passengers to their final destination will have you eyeing the illuminated exits and questioning the decision to endure the merciless intensity of the next two hours.

Naomi Watts, once again with an English accent so impeccable she ought to be given honorary English citizenship, portrays one half of a well to do couple on an ill-fated holiday with their three kids in Thailand. Ewan McGregor is the husband, clearly bringing much of his own experience as a father of four to the role. Giving way early on to the most important character in the film, the tsunami itself, the actors have only fifteen minutes or so to sketch the family dynamics and make us care before the carnage. Watts' Maria has a faltering connection with her eldest boy Lucas which grows into an inseparable bond once Maria is severely injured and Lucas is thrust into adulthood, caring for her and making her feel safe in a dangerous and hostile environment. McGregor's Henry is a well-intentioned workaholic, desperately wanting to spend quality time with his younger sons Simon and Thomas but unable to stop his eye from wandering to his blackberry. Even as they're being pummeled by water, debris and all manner of special effects, the actors ensure that the courage of this real life family and their will to survive grabs a firm hold of your heart. Watts, who bears the worst of violent waters in an incredibly demanding, physical performance, throws herself into the enormity of Maria's unimaginable situation, letting the power of the wave dictate her emotions rather than acting hysterically in order to be heard over the deathly cacophony.

By far her best turn since the career breakthrough of Mulholland Dr, for Watts this caps a great run of roles over the last few years in which she just seems to get better and better. Special mention should go to McGregor, who after the initial separation of the first wave is missing in action for a good forty minutes, so that by the time we've been left bruised beaten and broken-boned by the trials Maria and Lucas are put through, starting over with Henry and having to get emotionally invested all over again is a lag in momentum and energy that most actors would struggle to overcome. McGregor has never been better, achieving a personal best in his frighteningly primal portrayal of a flailing family protector in his darkest hour.

Of course neither of the lead performances would be so effective were it not for the work of incomparable casting director Shaheen Baig, who after putting sociopathic faces to an era-defining interpretation of Brighton Rock's Pinkie and Rose as a Leopold and Loeb type suicidal couple, finds a trio of boys whose faces effortlessly express the distress of separation anxiety, revealing barometers of the turbulent, shifting weather within. Tom Holland as Lucas, fresh from his turn as Billy Elliot on stage at the Victoria Palace, has chemistry with Watts that's more deeply felt and believable than many of her far more experienced big name co-stars over the years. An impressive film career beckons.

During the tsunami itself, hearts will be in mouths, fingers will claw at seats and viewers will continually grimace at the death and destruction it leaves in its wake. Whereas Clint Eastwood's version of the same catastrophe in Hereafter came off as a set-bound, Disneyland log flume ride, irresponsibly using real life tragedy as a dramatic backdrop, any awe inspired by Bayona's team is not for want of showy exhibitionism, simply a side effect of honestly conveying with as much authenticity as possible, what it felt like to be at the mercy of nature's wrath.

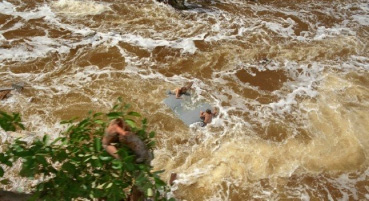

As Maria is caught in raging undercurrents, whipped around and cut to ribbons, bones sticking through her skin as if she were Bruce Willis in a Die Hard film, the extraneous amount of ravaged flesh on display makes it clear that the film strives not to be enjoyed as mindless entertainment, as so many films of this scale often are. The make-up department does exemplary work in showing the severity of fatal injuries inflicted upon Maria and tens of thousands of unsuspecting strangers. When Lucas sees the extent of his mother's wounds saying ""I can't see you like this Mum", we can hardly look either, such is the awful fragility of human life. On their way to higher ground and the refuge of a still standing tree, Maria is in such a bad state that we're not sure if the cracking we're hearing is the sound of branches crunched underfoot or the breaking of bones, wincing in anticipation of the worst with every agonizing step. It's an agony aggravated by cinematographer Oscar Faura's, richly atmospheric unforgiving imagery, turning up the sweaty humidity of tropical heat in burning colours.

For the first time in recent memory, the use of found footage, not only serves an authentic purpose but carries real horror and weight, reminding us that what we're watching is so much more than dream factory fabrication, casting our minds back to unbelievable images that flooded news reports and YouTube at the time of the incident.

Undeniably a difficult watch, as a bravura display of envelope-pushing filmmaking, it couldn't be more thrilling. Remember that "can't believe your eyes" wow factor the first time you saw Jurassic Park or Titanic? Love it or loathe it, we all went to see Cameron's sinking ship at least three times in the cinema, in part because of the peerless feat of physical filmmaking pulled off by the set builders and stunt team. Watching it in 2012 on Blu-ray, the apparently endless technical ingenuity in bringing another historic tragedy to the screen, impresses now more than ever.

In what is surely the best big screen spectacle since either of those films, and certainly the most powerfully concentrated display of in-camera ingenuity that largely avoids digital trickery, one marvels at the brain-knotting means through which the harsh realism of such peril was achieved. In one particular sequence, which sees Watts dragged underwater, totting up all the various elements necessary to realize the scene is staggering. Cutting between Watts and her stunt person, you've got an actress doing intricate wire work in a water tank and for thrashy violent close-ups, having to jolt the chair on which she's sat – to which the camera is also attached – in perfect synch with precisely timed mechanical effects; trucks, telephone poles, glass, and bricks, all moving at variable speeds in water than they would otherwise. The margin of error for capturing everything in the frame, perfectly coordinated and at the right angle without having to take the time to painstakingly reset the entire sequence is huge. Not to mention that with all the roiling debris in the tank, controlling the density and opacity of the water so that everything that needs to be seen is clearly visible, is yet another felicitous factor to consider.

Orchestrating a punishing symphony of telescopic crane shots, aerial shots, cable cams, remote control cams and camera operators underwater all working at differing tempos and intensity, Bayona creates the sensation of visual whiplash. When he takes to the sky for bird's eye view shots of floating calm against the chaos, the breadth of the destruction, the catastrophic death toll and nature's cruel indifference renders the viewer dumbstruck and slack-jawed.

With all the money, time and manpower that goes into crafting such breathtaking setpieces, making it all look frighteningly spontaneous and not planned down to the tiniest detail, it's hard not to take issue with those bent out of shape by the films ethnographic slant. Nowhere in his thoroughly dismissive review on the site of the same name does Ed Gonzalez find time to laud the film for its astounding technical accomplishments.

To the charge of it being a latently racist cliché of whitewashed first world privilege, in which we only see the suffering of white tourists, it's admittedly hard to ignore the film's very limited number of native speaking roles, but does anyone seriously believe this so-called ignorance has to do with anything other than simple economics? To execute a film of this magnitude you need star names that will appeal to audiences around the world and make good on the film's gazillion dollar investment. You put anyone who isn't white, well-known and English speaking in those leads and audiences brainwashed by marketing, consciously relegate it to the status of foreign film and box office death. Until the people rally behind something with subtitles and make it the year's biggest money spinner, it ain't gonna happen. Do you really think a Spanish director, producer and writer artistically wouldn't have preferred to keep the Spanish origins of the real life family if they'd had a choice? With what little manoeuvring room he has, screenwriter Sergio G. Sanchez at least does his feeble best to make this family citizens of the world, with Henry working in Japan and Maria's profession as a doctor seeing her healing people of every ethnicity.

Even if the film is unequivocally guilty of being hesitant to cast non-Caucasian actors, we only have to remember that this is simply one perspective of that day out of hundreds of thousands. And on that day many rich Western families on nice expensive holidays lived through the same horrors, so I'm not sure how the white experience is made any less relevant than the testimonies of the many nationalities affected, indigenous or not. That it all takes place on tourist islands far away from the city centre, catering to and dependent upon white affluence, it can hardly come as a surprise that the story’s perspective is similarly whitewashed.

As a story that's just one part of a much bigger picture, motion pictures certainly don't come any bigger. Make no mistake about it, The Impossible is world-class blockbuster rivaling the work of Spielberg and Cameron and unsurprisingly, it demands to be seen on the biggest screen you can find with the best possible sound. Combining terrifyingly realistic effects with heart-wrenching performances, it's perhaps the most expensive horror film ever made but also a powerful testament to the human spirit, whipping up the kind of raw emotion its soulless CGI contemporaries can only dream of. As that rare convergence of commerce and craft, a special place in the history of event movies is already assured.

*Another reason the sound was so impressive is due to The Impossible being the First Film with imm Sound's Immersive 3D Sound system. How this affects your experience in the multiplex I'm not sure. More can be read about Ort's revolutionary work here.

|