|

Charming the pants off just about everybody at Sundance way back in January and winning the grand jury prize, Benh Zeitlin's Beasts of the Southern Wild hit the ground running and hasn't looked back since. Nine months and one Caméra d'Or later, the film's ever-increasing momentum shows no sign of flagging as the film put another feather in its cap Saturday night, taking home the Sutherland Award in competition at the 56th BFI London Film Festival. Oscar is so certain at this point, you'd be foolish not to take a trip down to the local bookies on Hollywood's big night. Categories such as best film, best director and best actress for the impossible-to-pronounce Quvenzhané Wallis are all likely bets. As Hushpuppy, an afro'd ragamuffin of wise-beyond-her-years perceptiveness and poise, eight year old Wallis (five at the time of filming) is every bit the deserving nominee and frankly, the likes of Jessica Chastain and Marion Cotillard better watch their backs.

Of course it's shallow politics that will ultimately decide a winner, a factor which rarely takes into consideration the quality of a performance, only the numbers behind the performer. Cotillard already has a best actress gong to her name for La Vie en rose as recently as 2008, so if she were to get a nomination it'd be a red herring, the Academy's traditional empty gesture of celebrating its own and of reminding the audience at home (in case you forgot) that this actor is officially a statue-carrying member of the award winner's club. The simple fact that she already has an Oscar and memory of her win is still fresh, means that a nomination would only put her there to fill out the pack and make up the numbers.

Those same numbers are heavily in favour of Wallis, who at eight years old would be the youngest ever recipient of the best actress award. The only thing Oscar might love more than a smaltzy heart-on-sleeve performance is playing a hand in writing its own history. Make no mistake about it, the chrome-domed man with a sword can't wait to be responsible for putting Wallis in The Guinness Book of Records. That the indelible performance of this prodigal non-actor child can stand tall amongst those much older who've been studying the craft for years is but a serendipitous bonus. And while we're talking politics, it also doesn't hurt that two of the film's most vocal fans are Barack Obama and Oprah Winfrey.

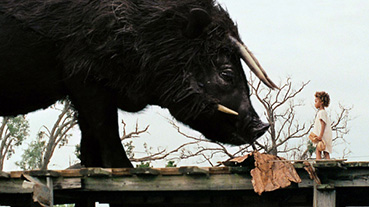

However, having already reached critical mass months before the Academy Awards, don't expect Beasts to sweep all the categories, particularly technical, which is a real shame as it's the one area where the the film really sets itself apart. The titular prehistoric stampeeders (mythic beats called aurochs) are beautifully conceived and captivatingly realised on screen, yet are sadly being overshadowed by the critical establishment falling in love with a child star.

While the film is a celebration of many things, it primarily seems to thrive on the power of wonder and imagination that burns bright even in a flooded Bayou slum. Rising waters embellish the film's form, which exists in a fluid state of pauperis and magical realism, where unadorned handy-cam work is punctuated by deliberately designed impressionistic set pieces. Each style blurs the edges of the other, and while it would seem obvious that such fantastical creatures have materialised from Hushpuppy's mind, her point of view from which the story is told, asks us to take it on trust that the beasts have been thawed out of the melting ice caps which have caused the flooding of her wetland community, appropriately called the bathtub.

Brave in the face of certain annihilation, Hushpuppy's Malickian ruminations on her place in a world coming to its end obliquely weigh Darwinism against a cruel God (here that familiar Malickian whispered reverence is delivered with a precious cuteness that would have benefited the self-parodic voice-over of Tree of Life). On either side of the equation, statements such as "The whole universe depends on everything fitting together just right" aren't tarred by the existential resignation of say, Bergman. Instead, loss and sorrow is tinged with hope and blown through a funnel of spiritual uplift. What's remarkable is how this community bands together in the hardest of times to take a stand of celebratory defiance rather than exhausted disillusionment.

This endearingly optimistic take on survivalism is something critics and audiences seem to really have responded to, a certain plucky resilience buoyed by the twee, but nevertheless neck hair-raising strings of Dan Romer and Benh Zeitlin's anthemic score, blared from on high in the sound mix, drowning (at least on the initial watch) some of the film's gratingly platitudinal qualities. Indeed, on the first viewing, it's a film all too easy to get swept up in, even as the filmmaker's dog-to-a-bone eco sentiments quickly become overbearing.

What can't be called into question is the daring scope of Zeitlin's directorial vision. Under the banner of the Court 13 collective, Beasts is a film made by the community it's about, the cast comprised entirely of a cast of non-actors (Hushpuppy's alcoholic father Wink is played by Dwight Henry, who owns the bakery right across from Court 13's offices). For all its child's eye view magic realism and the way in which it parades its mythic theatricality, such an approach lends the film's social commentary a one-of-a-kind authenticity and resonance. That the entire film is a blatant allusion to hurricane Katrina never feels too on the nose because we're watching people on screen who were directly affected by the tragedy. HBO's Treme was first to hit on this topic in the mainstream of course, but whereas that series chronicles an actual township of people with roofs over their heads and bills to pay, Beasts focuses on the most marginal of the marginalised, forgotten and cast out of the Crescent City into nature where they hunt and forage for food.

Out in nature, Zeitlin presents a hardscrabble America rarely seen on screen. An interspecies harmonium where man truly understands and appreciates his place in the bigger picture; respectful of elements he is at the mercy of and animals he is dependent on. In order to understand this, one has to go back to the primitive, as seen in the scene where Hushpuppy is encouraged by her father and friends who are feasting on crabs, to "beast it" A chant rises up over the table telling her not to use knifes or forks but to rip and claw at her food with the same respect any other animal in the food chain would show her if she were the one being eaten. This is just one of many scenes that demonstrate how truly attuned to nature the filmmakers are, in a way that Terrence Malick has only felt falsely connected his whole career, in awe of that which he can't fully comprehend. There's no sense of admiring blades of grass through a microscope here, you can feel, smell and taste it all: the rain on corrugated roofs; the squelch of a bucket of live crabs; the breeze through the trees, the buzz of crickets in magic hour. As a "buffet of the universe," Beasts is the beating heart to Tree of Life's "creation of the universe" screensaver light show, forgetful of the fact that on the sixth day God created man.

If Zeitlin captures a perfect sense of man's interconnectedness to all things, he can't resist pushing the point far too hard throughout. The heartbeat of every animal Hushpuppy presses her ear against rings out loud and clear as she talks about seeing "everything that made me, flying around in invisible pieces" whenever she closes her eyes. To many, such mindless babble from the mouths of babes sounds cute rather than preposterously incoherent. What kind of six year old talks like this?

After so painstakingly painting a tactile, earth tone portrait of Louisiana hardship, why smear it with spiritual guff disconnected from that reality? Zeitlin has talked about putting all his "wisdom and courage" into Hushpuppy, evidently enough to tip precociousness into preciousness, a point made by The Daily Mail's Christopher Tookey in one of the rare dissenting reviews beside this one. Zeitlin is so assured with the world-building, you wonder how it escaped him that his main character is little more than a mouthpiece.

As the sun sets on another day that Hushpuppy and her waterlogged neighbours have lived through to see the end of, the slick of hard won sweat and the celebratory swish of cold beer is enough of a self-reliant lullaby, that scripted pretentious poetics only show the film to be in love with it's own sense of wonder. Way too much meretricious voiceover is incidentally, another thing Oscar can't get enough of, so for all my moaning Zeitlin is clearly on to something.

I certainly won't bemoan people responding as they have to the performances. Wallis stares, howls, and flexes like a prizefighter (literately at one point). Her diminutive frame rocked by untamed energy which burns across the screen. And please, in all this excitement, if the decision to heap the film with accolades is one that's already been made, then let's not forget Dwight Little come awards season. Wink is a booze-tweaked liability and part-time patriarch, dispensing fatherly wisdom only when the mood suits him, and a good lashing just as often. The Evening Standard's Charlotte O' Sullivan notes Wink's violent insistence that Hushpuppy hold back her tears. Watching him instil in her the belief that she is "the man!" is "both touching and painful" precisely because that's exactly what Hushpuppy must become, picking up Wink's slack as a father and caring for them both. Hushpuppy learns a harsh truth learned at a tender age; that universal harmony can only be achieved if we first love – or at least come to terms with – those who brought us into the world. Wink's eventual realization of the multiple ways in which he's let his child down and the how he's failed to protect her now their roles have been reversed is a silent acknowledgement that lingers on both faces, a moment that doesn't resort to tears when it knows the audience will willingly provide them and all the more staggering for the fact that two non-actors make this bond between father and daughter so heartbreakingly real.

If only the film had shown similar restrain elsewhere. Tapping into the senses through the natural world, it then proceeds to overload them. Every time the music swells (which is often) Zeitlin seems far too concerned with pumping the blood and thumping the heart rather the telling a good story. Hinged on whimsical set pieces, the screenplay is sorely lacking in dramatic structure, something the rough-hewn docu-drama aesthetic can't excuse. And though I was moved by such an overwhelming display of community fortitude, this to is overstated. I fail to see what's so magical about being poor and black in post-Katrina Louisiana. As a fairytale, it's condescending or at least naive.

When describing his reservations about The Artist, the site's own Camus likened going against the tsunami of journalistic amour to peeing on the good book. In stopping to question the ferocious love for Beasts, I feel as though I just peed on a whole stack of bibles. While Beasts has much more going for it than the ersatz simulacra of The Artist, I certainly didn't fall in love with it as many have and currently have it ranked as the 40th best picture of the year. Not exactly the kind of poster-ready recommendation you're likely to read everywhere else.

Wondrously original? Certainly and that's enough, a quality that ought to be prided in films above all others, but one of the year's best films? Far from it.

A recent comment made by Paul Bettany in our video interview that'll be published early next year speaks to the seeming pack mentality of critics falling over one another with the same adjectives. Responding to the critical wrath visited upon his wife Jennifer Connelly's latest, Virginia from the pen of Oscar-winning Dustin Lance Black, he lamented the time when critics used to have their own mind and took pleasure in taking the opposite opinion of another critic. Nowadays, it so often feels as if they're waiting in the wings for clarification from Variety or The Hollywood Reporter on whether or not it was a good film before passing their own verdict.

In this case, mine is a minor voice swimming against the tide, but all the same, there's something insidiously Stepford-esque about forty foot waves of critical adulation come awards season. Much like the thundering herd of the film, the critics bow only to Hushpuppy and as superlatives run wild, my advice is simple: enjoy the film for transporting you somewhere you likely haven't been before but don't let your own expectations get trampled by the hype.

Beasts of the Southern Wild played the 56th BFI London Film Festival. It went on selected release across the UK October 19th.

|