|

There are those, I have no doubt, who will claim they emerged from the womb with an appreciation for cinema of all types, whatever its place of origin. If you meet such a person, do them and me a favour and smack them in the mouth. They're almost definitely lying. If we are lucky, we grow up in a household in which we are exposed to a variety of film and music, and are thus able from an early age to appreciate a wider range of art and entertainment than the home-grown or Hollywood product we are so relentlessly exposed to. Before the arrival of home video, this was a damned unlikely prospect for the average Jane and Joe, and even years after its arrival there are precious few teenagers who will not choose the immediate thrills of the blockbuster over the less obvious and more demanding pleasures of a European family drama. That's part of growing up. Kids like to think they're Tom Cruise or Russell Crowe, not Mathieu Amalric.

I spent my cinema-going youth, as did many of my friends, consuming a diet of Hollywood movies and the occasional British flick, laced with the unpretentious thrills of Hong Kong martial arts cinema. I discovered the older Hollywood product at a surprisingly early age (I have my father to thank for that), but I was in my late teens before I began experiencing the various delights of world and independent cinema. It would be another good few years before this became my viewing material of choice, and when I first encountered Paris, Texas – my first Wim Wenders film – I was on my way out of Hollywood but still only dipping my toes in modern European cinema. It was an odd screening anyway. I went with my girlfriend of the time and a good friend who had this thing for Nastassja Kinski, which was frankly our main reason for being in that cinema on that day. I don't know what I was expecting and can't remember just why I reacted as I did, but the film really pissed me off. I was bored and irritable and I remember once going to the toilet at one point for no other reason than to be away from the screen, just for a short while. Late in the film, after listening to a man relate what felt like an interminably long story, I watched him get up to leave and my heart began to lift, but when good old Nastassja stopped him from doing so I wanted to leap through the screen and strangle her.

None of us came away happy. Less than a year later, the girlfriend and I had parted company, and a few years after that the friend in question had gone his own way. Before we drifted apart, he gave me a soundtrack album, one he insisted I listen to without prejudice. It was Paris, Texas by Ry Cooder. Despite my surprise that he would do such a thing – he had been there after all – I gave it a listen. Ry Cooder was cool in my book and had contributed to some other fine film soundtracks, and over the course of the next few months I became slowly hypnotised by the soulful twanging of Cooder's guitar, by the images it conjured up in my mind, by how good it sounded when you were on a long journey. I even sought out the tune that was the principal influence on the score, Blind Willie Johnson's Dark Was the Night Cold Was the Ground. Then a chance meeting briefly re-united me with the ex-girlfriend. We shared memories and talked film and Paris, Texas came up again. She'd seen it a second time and had really enjoyed it. I thought she was nuts. Then again, I'd always thought that.

By the time the opportunity and inclination to watch the film a second time coincided, a fair few years had passed and my embracement of the non-Hollywood product was pretty much complete. I had become hooked on minimalist Iranian drama, its focus on character and place over of story being something I could never have imagined even tolerating just fifteen years earlier. So I believed I was ready. I knew the soundtrack, I'd seen a few more Wenders films, and I was no longer in a hurry. If the film wanted to take its time, then I was prepared to walk with it. And there was another factor, one that relates to human experience. But I'll get to that.

Watching the film a second time after such a long period and after so many non-Hollywood films was a very different experience. You might even call it a revelation. I could not, for the life of me, recall just what it was about my state of mind on that first viewing that had made me so blind to what was now so obvious. The film no longer felt slow, but entrancingly unhurried, and the pace seemed just right for the story being told. You want speed? Go see Jan de Bont. If you character and emotion and a vivid feel for landscape and place, then Wenders is your man.

What I failed to capture in this rediscovery is that all-important first viewing experience, approaching a film and being hooked but unable to guess how the story will unfold, something some of the best European cinema specialises in. First time round I didn't know but didn't care, second time I cared but already knew the answers. My loss. And it is a loss. Roger Ebert has said that one of the film's finest qualities is that you could not predict where it was going to take you, and for the true newcomer this is absolutely correct.

It starts in captivatingly enigmatic fashion, with the image of a man named Travis wearing the wonderfully ragged face of Harry Dean Stanton walking purposefully through the barren heat of the Texas Badlands. He runs out of water but stumbles across a bar so isiolated I couldn't wondering how if it ever had customers. All it has in the fridge is beer and for some reason this won't do the trick, so he crams a couple of ice cubes in his mouth and promptly falls into a faint. He is revived and examined by a large German doctor, who finds amongst the man's possessions a phone number for someone who may just be a relative, so gives him a call. The number belongs to Walt Henderson (Dean Stockwell), who lives in Los Angeles and makes advertising hoardings. He's also Travis's brother. Travis, it emerges, has been missing for four years, ever since he broke up with his wife Jane, and his young son Hunter now lives with Walt and his French wife Anne. Walt drives down to Texas to collect his long lost brother and wants to know what happened, but Travis isn't talking, having drifted into an almost catatonic trance. Walt takes Travis back to L.A., where he slowly opens up and attempts to bond with his confused and uncertain son. But the question of why Jane left and where she now is remains, and Travis decides the time is right to find her and confront her about their past.

This is a film about loneliness and loss, and rarely, if ever, have I seen the essence of either so vividly captured on film. Now I have to admit to speaking from the viewpoint of someone who has never really been lonely nor experienced romantic loss – I enjoy being on my own and my relationships have all ended either amicably or with a cheery request not to bang the door on the way out. But I nonetheless understand loss only too well, and how it can create its own very specific sense of loneliness. I've lost people very close to me and I still miss them every single day. Losing someone suddenly, unexpectedly, permanently, leaves a wound that never completely heals. Small things, everyday things, remind you of them, remind you of the good times you had together and make you wish you could talk to them again, just one last time. That these losses happened between my first viewing of the film and the second just may be a contributory factor to my more receptive appreciation of its qualities.

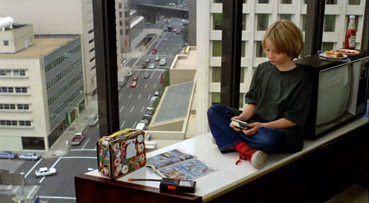

There's a scene – a simple but crucial scene – that for me defines this element beautifully. Cleaned up and communicative, Travis is invited by Walt to watch one of his old home movies, a record of a family trip to the coast made when Travis and Jane were still together and very much in love. Everything about this sequence is perfectly judged. Although a family activity, Travis sits alone and closest to the screen, connected to the others and yet still isolated from them. As the film rolls, the camera focuses on his face and his expressions, as his emotions are barely kept in check but still heartrendingly visible beneath the surface. It's all in the gentle twang of Cooder's score, Wenders' expertly restrained handling, and that face. Ah, that face.

Harry Dean Stanton is regularly categorised as a 'character actor'. What this means is that he was never destined to be a big star and only by the luck of the draw gets to carry a movie. Character actors are seen by Hollywood as not being pretty enough for that. They don't have star quality. The studios want stars not because they are the best actors that they can afford, but because they are bankable faces, good-looking box-office draws whose mere presence suggests a quality product (a notable exception to this general rule has to be Tom Hanks, whom few would describe as the sexiest man in movies but who can almost guarantee a sizeable return on your investment). Asked to name my favourite actors, I inevitably will give you a list that has only character players on it. They generally have more interesting faces, have a wider range than their overpaid brethren, and to be honest often have a greater command of their craft. They can appear in just one scene in a film and steal it, can add a touch of realism to the unreal, and can even enliven an otherwise slack enterprise, at least while the camera is on them. But films want us to focus on the leading players, to journey alongside and empathise with them, and those on the fringes too often get little more than a critical nod. It's thus a treat when a character actor gets to play the lead, allowing everyone to focus their attention on what they can do and show us what great movie acting really is. Harry Dean Stanton does that here. He doesn't act with his hands, he acts with his eyes. It's all in those eyes, every emotional twist he goes through, every memory he recalls, every anxious, uncertain moment. It's real. It's believable. And it's at its most quietly powerful in this simple little scene.

There's a moment towards the end of this sequence when Travis looks over at Hunter and their eyes meet and a few friendly words are passed between them. It's a moment that speaks volumes. At this stage the boy has still yet to openly acknowledge Travis as his father, but with that quiet exchange, a small door opens that allows the bonding that follows to develop within the realms of credibility. Their rediscovery of each other is the meat of the film's midsection, leading to a final act that takes both on a journey to find the estranged Jane. That Travis and Jane are destined to meet up again is inevitable – you don't cast Nastassja Kinski and then consign her to a few glimpses in a home movie – but the encounter is teasingly delayed, in part by Travis's own apprehension at facing her. The circumstances of her whereabouts (which I'm not going to reveal here) allow Travis a way in that avoids direct confrontation and makes for a more cinematically and dramatically satisfying scene than a simple face-to-face conversation ever could. This was the sequence that really finished me off on that first viewing, one I now find as captivating as anything in Wenders' oeuvre. Key to its emotional power is the perfectly judged performances of Stanton and Kinski – Travis's sad, lengthy and mesmerising monologue in particular, coupled with Jane's slow surrender to her memories, burrows into the emotions of the receptive viewer. You don't need to have experienced a traumatic break-up to feel for Travis and Jane – where once I groaned, I now find myself wiping away tears. Yes, it's THAT affecting.

Having sat on both sides of the critical fence on the film, I am able to appreciate the opposing viewpoints that are inevitably levelled at it. Yes, it's slow moving and lacking in major incident, and yes, the narrative climax consists of a nothing more dramatic than a conversation, but this all feels so right for these characters and this story. The small detail, as ever with Wenders, is a pleasure in itself. There are a couple of character inconsistencies (Travis's insistence on getting the exact same rental car as before rings of obsessive compulsive disorder, a trait evident nowhere else in the film) and occasional shifts in tone that jar just a little, but for the most part Paris, Texas is very special cinema, beautifully written by playwright, author and occasional actor Sam Shepard (that's him as Chuck Yeager in The Right Stuff), strikingly photographed by Robby Müller (on the commentary track Wenders credits this as Müller's masterpiece, which is saying something in itself) and scored to perfection by Ry Cooder, to the degree that it really is impossible to imagine the film without his music.

It's likely a chance thing that Shepherd and Wenders chose the name Travis for their lead character, but its nonetheless interesting that cinema's most famous bearer of that name, as played by Robert De Niro in Taxi Driver, was also a disconnected loner. But where Travis Bickle went to war on his problems, Travis Henderson sets out to make peace with his. It's a moving and involving journey that's not going to work for everyone, but if your first encounter with the film is a little infuriating, then take it from someone who knows, if you give it a little time and a second chance, it may just surprise the hell out of you.

At first it looks as if the colours are a little over-saturated and the brightness a tad strong on this print, until you realise that this was the intended visual style, something that would nowadays be done digitally in post-production but was then achieved through the use of a polarised filter. With this in mind, this is a strong transfer, with good detail and nicely rendered contrast and shadow detail. The odd digital artefact pops up here and there, but they are minimal. The framing is 1.78:1 and the picture is anamorphically enhanced.

There's not a lot to choose between the Dolby stereo 2.0 and surround 5.1 tracks – neither are particularly spacial, but both are clear and clean of noise. The music sounds fine and even the quieter dialogue registers well.

Commentary by Wim Wenders

Of the three commentary tracks in Anchor Bay's Wim Wenders Collection, this is my favourite. Although on his own here, Wenders provides a wealth of always interesting detail on the making of the film, from casting and working with the actors to choice technical details, including the film's striking use of colour (it's here that I learned about the use of the polarised filter). Particularly surprising is that filming commenced with the story and script only half written, the intention being that they would shoot chronologically and that Shepherd would, once he had watched how the actors interpreted the roles, write the second half accordingly. This all went a little pear-shaped when Shepherd went off to another project, resulting in a second half that was written by him from notes sent by Wenders. You'd never know it.

Deleted Scenes (22:42)

A collection of deleted scenes and shots with commentary by Wenders, who apologises for the scratches and dust, "but that's the way we found it." The director provides considerably more information on the material and the reasons for its removal than on the deleted scenes on The American Friend DVD, and does so in interesting and sometimes entertaining manner. A worthwhile extra, although it would have been nice to have the option to watch the scenes without the commentary as well.

Festival at Cannes (3:43)

DV footage of the blitz of flashguns that accompany the cast and crew arriving for the Cannes screening. Nothing about the Palme d'Or win, though.

Trailer (2:03)

What looks like the American trailer does a reasonable job of selling a film that doesn't have obvious commercial appeal.

Photo Gallery

32 stills from the film, which we know from Wenders commentary on the deleted scenes were lifted from the film itself.

Out-takes (6:38)

The unused footage from the home movie sequence watched in the film, presented 4:3 and in good shape.

There are also, if you trip down to the bottom of the Bonus Features menu, below the lower 'Menu' button, detailed Biographies for Nastassja Kinski, Harry Dean Stanton and Wim Wenders.

Humble pie is a dish I'm happy to eat if it means I can rediscover a film in a new and more positive light, and that's certainly been the case with Paris, Texas, a work I once curtly dismissed but have since completely fallen for. It's one of the best featured discs in The Wim Wenders Collection, but that's because it's the same disc that has been available as a stand-alone for over four years. It's still a key inclusion, and if you don't already have it then it's a further compelling reason to get the full set.

|