| |

"He is, I would say, one of the few absolutely pure auteur filmmakers currently working in scary movies, and therefore should be prized." |

| |

Kim Newman on director Kurosawa Kiyoshi |

As the sort of upbeat music you'd expect to hear on a cheery children's television show tinkles away on the soundtrack, a middle-aged man walks purposefully through the streets of Tokyo and into a darkened underpass, where he helps himself to a length of water pipe, which he then takes home and uses to calmly beat a sex worker unconscious, then carving a large cross in her throat and upper chest that severs both of her carotid arteries. When the police arrive at his house, the man appears to have fled without his clothes, but detective Takabe finds him hiding in a small utility cupboard, naked, hunched up and shaking with fear. Back at the police station, the man admits intent, but claims that afterwards he was stunned by what he had done. This, we learn, is the third such case in the past two months. No details about the specifics of the killings have been leaked to the press, and no connection between them has yet been discovered. The only similarirty is that up until the moment they committed their crimes, each of the perpetrators had led ordinary lives and were considered rational people.

On an otherwise deserted beach in Shirasato, elementary school teacher Hanaoka exchanges words with a young drifter who does not appear to know where or even who he is. When the drifter pleads for help, Hanaoka takes him home and discovers the name 'Mamiya' sewn into his coat. "That's fine" the drifter responds distractedly, "Mamiya can be my name. It probably is." When Hanaoka attempts to question him further, however, his efforts are frustrated by Mamiya's inability to recall things he was told just a few seconds before, responding with the sort of attention-deficit questions that an infant might ask. Then Mamiya quietly presses Hanaoka to tell him about his wife, Tomoko. The following day, Mamiya has moved on and Hanaoka inexplicably kills Tomoko by severing her carotid arteries with a cross-shaped wound, then hurls himself through the upstairs window of their house. Again, no motivation for his actions can be found, and when questioned in hospital later, a stunned and ultimately distraught Hanaoka cannot understand why he murdered his wife, though claims that at the time it seemed the natural thing to do.

Twice before in reviews of his films I've told the story of how I was first introduced to the cinema of Kurosawa Kiyoshi, and loathed though I am to repeat myself (again), it's more relevant to this film than any other in this director's fascinating oeuvre, and particularly significant to this release. Back in 2004, I was visiting a friend who worked at the Japan Academy of Moving Images (which was founded by the great Imamura Shohei), and on my final day there, during the course of an evening of cheerfully heavy drinking in a Shinjuku bar, I was given a DVD of Cure by two of the school's students as a parting gift. Their reason for selecting that particular present (quite apart from the fact that it was a rare Japanese DVD with optional English subtitles) was that its director, Kurosawa Kiyoshi, was a filmmaker whose work they deeply admired but whom they felt was not getting his due attention outside of Japan. I was blown away by the film and wrote a review of it for the site (which this review is an expended and amended version of), knowing that the Japanese disc would likely not be easy or cheap to import, but in the hope that some enterprising UK distributor would release the film on DVD here in what was then the near future. To my astonishment and dismay, that failed to happen. As far as I'm aware, the first Kurosawa film to land a UK DVD release was his 2001 Pulse [Kairo], which was followed by his 2003 Bright Future [Akarui mirai], both of which were put out by the long-since departed Tartan. Neither were exactly standard-setters on the technical front. Ultimately, it was the 2009 Tôkyô Sonata that brought Kurosawa the more widespread critical attention he deserved in the UK, and since then we've been treated to his sublimely unsettling return to genre filmmaking, Creepy, and have even seen two of his earlier V-Cinema features, The Serpent's Path [Hebi no michi] and The Eyes of a Spider [Kumo no hitomi] released on UK DVD. Yet despite the fact that Cure got a favourable mention seemingly every time a new Kurosawa film was discussed or reviewed and the fact that it is widely regarded as the director's breakthrough film, we've had to wait a staggering 14 years for it to land any sort of release in the UK.

Cure is often cited as an early work of the internationally successful Japanese horror (or J-horror) cycle, which was memorably kick-started by Nakata Hideo's Ringu in the year following Cure's Japanese release. As much a detective story as a horror tale, Cure differs from most of the other films of this cycle in its absence of clear supernatural elements and refusal to indulge in jump-scares, instead creating a chilling air of sometimes inexplicable menace and becoming as disturbing in its implications as what it is prepared to show or to have its characters surmise.

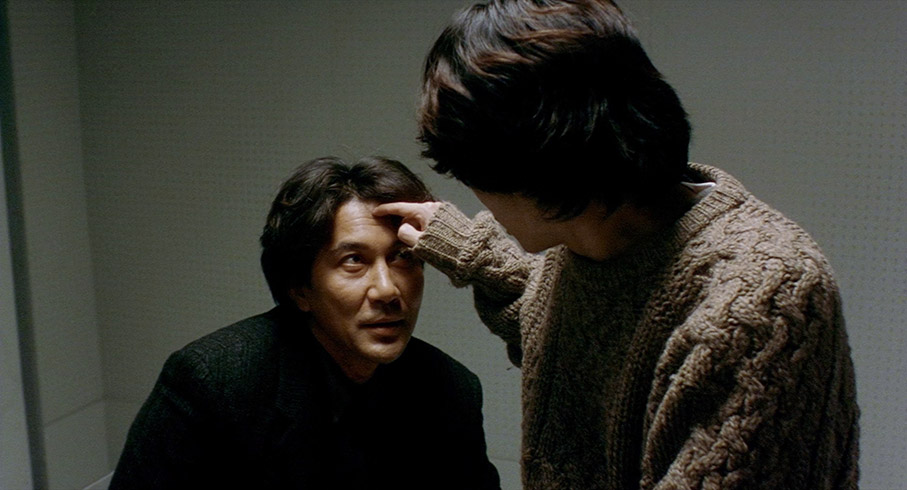

Central to the story are the characters of Takabe, the detective who is investigating the killings, and Mamiya, the young man who, through a process of hypnosis or auto-suggestion, appears to be provoking them. This may sound like a setup for a dark but structurally traditional police thriller, one in which the police repeatedly uncover new information but are always one step behind their elusive prey, until the inevitable breakthrough and the final showdown between detective and killer. And yes, the detective here does use his investigative powers to track down vital clues, and there is something of a showdown between detective and prey in the later stages, but neither play remotely to expectations – most of Takabe's most effective detective work is done after Mamiya is in custody, and the final showdown provides neither visceral thrills nor a real sense of closure for a story that looks set to continue long after the closing credits.

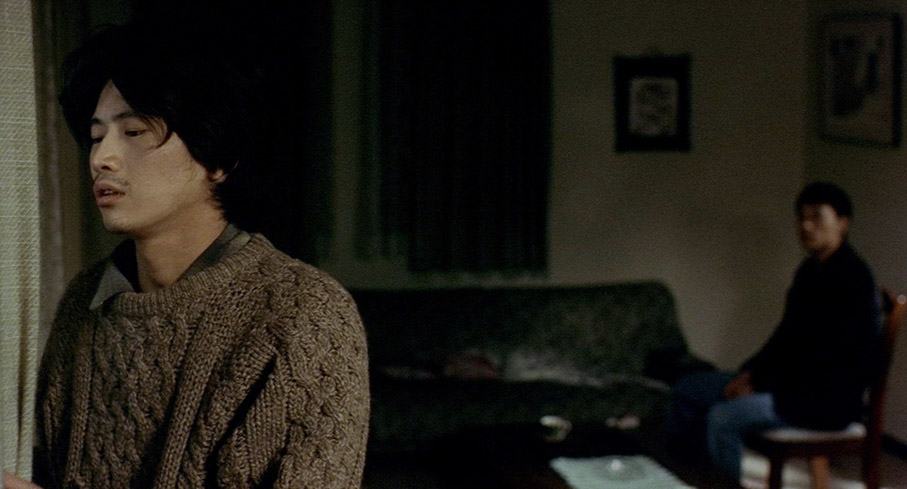

Everything in the film revolves around these two men and their eventual interaction, although this does not mean that we ever really get to know either that intimately. Mamiya in particular remains a mysterious and deliberately perplexing figure throughout. Is he just a psychology student whose study of hypnosis has driven him off the deep end, prompting him to lose his marbles and encourage others to do likewise, or is there a more supernatural aspect to his being? An unlikely-looking threat, this dishevelled, shuffling and seemingly wasted young man was apparently once a functioning member of society, but along the way something has happened to transform him into, well, whatever it is that he has actually become. Takabe's psychiatrist colleague Sakuma, at a loss to explain the killings and the dazed response of the murderers when questioned later, offers up the old adage, "The Devil made him do it." Is Mamiya a demon in humdrum, everyday form? Mamiya himself talks at one point of being emotionally inverted – "The things that used to be inside of me are all outside, so I can see all of the things inside of you, but the inside of me is empty."

Early on in the story, it becomes clear that Mamiya knows things about the private lives of those he targets that he shouldn't be privy to, suggesting an ability to read his victims' minds ("I don't remember anything. You do," he tells one of them). But later, when he pulls the same trick on Takabe, it turns out that he extracted the information from a talkative detective who has been assigned to guard him, a man Takabe then beats senseless for his indiscretion. Takabe, meanwhile, is dealing with his own emotional issues in the form of a wife with a deteriorating mental condition, one whose symptoms include an inability to recall recent events, something that directly echoes Mamiya's own apparent confusion. This increases Takabe's frustration with Mamiya, as the boy's refusal to respond to simple requests sharply reminds the detective of his own problematic home life, whose nightly ritual include turning off an empty but steadily rumbling tumble dryer that his wife repeatedly and for no reason switches on.

One obliquely suggested possibility is that Mamiya is unlocking a closed part of the brain to which our darkest thoughts are confined and kept supressed by morality. Having initiated the hypnotic process with Hanaoka, for example, Mamiya then asks him, "Tell me more about your wife," an enquiry that causes the man's gaze to falter. Kurosawa cuts away from the scene at this point and we are left to wonder what was hiding behind that troubled look, and just what information Hanaoka was prompted to divulge. As part of a fragmented but innocent-seeming conversation, Mamiya also prompts beat cop Oida to reveal that sometimes his job is "difficult." We never find out more than that, but this is a middle-aged man with a much younger and more disciplined partner, a man he coldly shoots dead the following morning. Was he resentful of his younger comrade? Was there a reason that he is still a beat cop this late in his career?

But it is Mamiya's encounter with female hospital doctor Akiko that is the most suggestive. This time Kurosawa does not cut away and we watch as Mamiya teases out of her a buried frustration at not having been able to become a surgeon in an all-male world, which the next day takes the form of destructive action. Takabe's increasing frustration at his wife, meanwhile, would seemingly make him an obvious candidate for Mamiya to turn into a killer, and part of the tension of the second half comes from the realisation that this could or even should happen. But Mamiya's attempts to hypnotise Takabe are frustrated by the detective's sometimes explosive temper, and it becomes increasingly apparent that he may be facing a different fate.

In the early scenes, the film does play like a carefully paced police drama with horror overtones, but a short while later expectations are overturned – twenty-five minutes in, Mamiya is sitting in a police box (a small, two-man police station) being questioned by a kindly Oida, who witnessed him leaping from the roof of a building. That he again turns this questioning around and prompts the policeman to shoot his colleague is not a complete surprise, but that he keeps the appointment at the hospital to which Oida has first taken him certainly is. Here he encounters Akiko and another potential victim, but by then he seems to be deliberately laying a trail for Takabe to follow.

There was much talk at the time about the boldness of having John Doe hand himself in to the investigating detectives in David Fincher's Se7en when a quarter of the story had yet to play out, but by the time Mamiya is in police custody for potentially inciting the killings, we are barely halfway through the film. Clearly Cure is not your ordinary police procedural. Stylistically, it further distances itself from the genre norm, with Kurosawa's decision to shoot many key scenes in wide shot in long and sometimes motionless takes giving the film a studied, observational feel, which somehow makes what takes place within that frame more chilling than it would had he made the traditional cut to close-up for emphasis. Combine this with the deliberately oblique approach to plot points and characterisation and you have a film that is destined to frustrate some viewers, but just as many should delight at not having obvious and overly familiar plot points spelled out to them in mile-wide, monosyllabic narrative strokes.

Atmospherically, Cure delivers in spades, with the encounters between Mamiya and his potential victims becoming increasingly unsettling, often aided by a superb use of sound effects and a dark and sometimes minimalist score, whose deep bass rumbles are sometimes inseparable from the effects track – the meetings between Takabe and Mamiya in the latter's cell in particular have an extraordinary sense of menace. Equally effective is the almost offhand nature of the killings – the two that we see are observed in wide shot and carried out unfussily and without emotion, and there is just enough suggested (the policeman collects a large knife from the police box after shooting his colleague, then starts to drag the body inside for a mutilation we never see) or glimpsed (the bloodstained bed in Hanaoka's house when the camera tracks back from the window through which he has jumped) to suggest something far more unpleasant than Kurosawa has chosen to show. The most startling exception comes with the almost casual discovery of Akiko at work on her first surgery patient on the floor of a public toilet, a brief but genuinely, skin-crawlingly horrific moment that will likely catch even the most prepared of viewers off-guard.

The toned-down approach to characterisation makes the performances secondary to just about everything else, despite the casting of Kurosawa favourite Yakusho Kôji (who will be most familiar to western viewers from his roles in Shohei Imamura's The Eel and Warm Water Under a Red Bridge and Masayuki Suo's Shall We Dansu?) as Takabe, whose sudden bursts of anger seem almost out of step with his otherwise low-key performance but which are crucial to why Mamiya appears unable to work his dark magic on the detective. For my money this works most effectively for a film that is not about how police track down a possibly supernatural killer, but the capacity for dark deeds that lies dormant within even the most seemingly well-adjusted and passive individual, and the fragile nature of the emotional and moral core that defines our very nature as 'civilised' beings. It explores the idea that evil, far from announcing itself with leering melodrama, is sometimes so quietly banal that it can pass by unnoticed, leaving us only with its consequences and questions about ourselves and our judgment of others. Cure delivers all this and more in a sinister whisper, and in a manner that demands but rewards patience and concentration. 14 years on from that revelatory first viewing, it remains for me one of the most compellingly and uniquely haunting films of late 20th century cinema.

The first thing that struck me about this welcome HD transfer of Cure is how deep and engulfing the black levels are, sometimes plunging whole areas of the picture into total darkness and intermittently sucking in the surrounding detail. But before we go accusing those responsible of pummelling the contrast and crushing the blacks in the process, it's worth noting that a direct comparison with the earlier Japanese DVD shows a similar absence of detail in these darker areas, the difference being there that the black levels were nowhere near as solid. Kurosawa uses darkness to conceal detail and to disconcert the viewer (in a particularly creepy hallucination sequence, Sakuma imagines visiting Mamiya's cell, a corner of which is dark enough for a figure to remain completely concealed from view) and this thus feels appropriate throughout and only adds to the film's unsettling mood. In daylight, the contrast feels absolutely spot-on, and even when light levels do drop the essential picture information is always visible. The colour is pleasingly naturalistic by day and has the usual warmer hues in night time interiors, and the detail, as you'd hope, is considerably sharper and more vividly rendered than on the Japanese DVD. The image is also clean as a policeman's whistle. This is how I always wanted Cure to look.

Back when I reviewed the Japanese DVD with its stereo only soundtrack, I ached for a 5.1 surround track, as it was clear Kurosawa's extraordinary use of sound would greatly benefit from being spread wide around the room and getting the extra punch that LFE bass can deliver. Well, hallelujah, Eureka have delivered on that very request with a DTS-HD Master Audio 5.1 surround that that is everything I always hoped it would be. The film's superb mix of sound effects and electronic drones is even more disturbing when rendered with this pristine clarity and level of bass, from the almost alien wind that howls over the Shirasato beach to the rumble of the overpass as Takabe visits the location from which the pipe used in the opening murder was taken. Even the pouring of water into a glass takes on new significance when heard on this track. You can also select a stereo 2.0 Linear PCM track, which is perfectly serviceable, but the DTS track is where it's at.

The English subtitles are clear and can be switched off if you so wish.

Kim Newman Interview (14:16)

The venerable Kim Newman delivers a cheerfully enthusiastic assessment of the film, champions Kurosawa as a genre filmmaker who is currently at the top of his game, makes some interesting comparisons between Cure and Larry Cohen's God Told Me To, discusses the film's underlying themes, and more. He also talks about the implications of the ending, so I'd definitely save this one until after you've seen the film.

Archival Interview with Director Kurosawa Kiyoshi (19:37)

An interview with Kurosawa, I'm guessing conducted for an American DVD release (the optional English subtitles use the American spelling of certain words). It's a useful grab, with Kurosawa discussing the inspiration for the film, the nature of identity, the use of frame space in his work, the difficulty of finding dilapidated locations in Tokyo, the meaning of the title (there are spoilers here), his long-standing relationships with production designer Maruo Tomoyuki and lead actor Yakusho Kôji, his favourite American films, and more.

Kurosawa Kiyoshi on Cure (16:53)

Presumably knowing that they were also going to include the above interview with Kurosawa on this disc, for this newly shot piece, the Masters of Cinema team wisely chose not to cover the same ground, and instead we get an interview that compliments the older one rather than duplicating it in any way. Here Kurosawa talks about how he first got into filmmaking via Pink Cinema (a uniquely Japanese sub-genre that weds drama to softcore porn) and direct-to-video films (known as V-Cinema), his long-standing relationship with actor Aikawa Shô, getting Cure off the ground, the improved opportunities to make horror or horror-themed films, and more.

Trailer (1:40)

A low resolution, windowboxed but smartly edited American trailer that, in the tradition of how foreign language films tended to be marketed in the west, avoids shots in which characters deliver any dialogue, presumably in the hope of fooling the subtitle-phobic.

Also included with the release version is a Collector's Booklet featuring an essay by Tom Mes, but this was not available for review. Mes really knows his stuff, however, so I'll put money on it being an enthralling read.

I've been championing Cure as a masterful low-key horror-thriller since I first saw it back in 2004, and the fact that it's taken a further 14 years to land a UK home release of any sort seems downright preposterous, particularly given the widespread acclaim with which Tôkyô Sonata and last year's Creepy were greeted. But the fact that it has arrived on Blu-ray as well as DVD, boasting a fine HD transfer, an excellent DTS-HD surround soundtrack and a handful of worthwhile extra features, almost justifies the wait. Despite strong competition, this is still my favourite Kurosawa Kiyoshi film and coming back to it after a break of a few years, it still got seriously under my skin. A terrific film and a most impressive disc. Highly recommended.

The Japanese convention of surname first has been used for all Japanese names in this review.

|