| |

"What is wanted is a conscious open revolt by ordinary people against inefficiency, class privilege and the rule of the old . . . Right through our national life we have got to fight against privilege, against the notion that a dim-witted public schoolboy is better fitted for command than an intelligent mechanic." |

| |

George Orwell, The Lion and the Unicorn, 1941 |

| |

"Violence in this country stems from a system which is sick, which is racist, which apparently has a boundless ambition to police the world . . . a system which relies more and more on the use of force, on the use of police to maintain itself rather than on consent or persuasion or the traditional techniques of democracy." |

| |

Tom Hayden, Rebellion and Repression, 1969 |

PART 1

Seldom can the Chinese proverb ‘You will be cursed to live in interesting times’ have felt more apposite. Our times have become so interesting, indeed, that it now seems incredible only five months have passed since Covid-19 first announced itself. Recent events on the banks of the Yangtze River and the Mighty Mississippi seemed to stretch time as well credulity. Until recently, few of us had heard of Wuhan, a city larger than London; fewer still could’ve described the flag of Mississippi, from which the confederate flag will soon be removed; and almost nobody had heard of George Floyd. Entire countries and their economies had already been shut down before we viewed footage of Floyd’s murder in Minneapolis and watched as anti-racist protests rolled across the world. Those protests and the pandemic threw the festering iniquities of neo-liberalism and the ancient injustice of systemic racism into sharp relief. The inscription on the Statue of Liberty that reads, ‘Give me your tired, your poor, your huddled masses who yearn to breath free’ now rings increasingly hollow for those everywhere declaring, after Franz Fanon, ‘I can’t breathe’.

The dizzying and disorientating events of recent months have accelerated changes in the way we live and work that would otherwise have taken decades to materialise. The office, the High Street and the cash economy may be gone for good. The economic impact of the pandemic has lead to what analysts are already calling ‘de-globalisation’. Then there are such changes to policing and society as may be made in response to the anti-racist protests and the changes to many women’s lives resulting from domestic violence. Those with mental health problems, too, will have suffered untold distress during the imposed isolation of lockdown. To say that there’s been a lot to process lately is to underestimate the spectacular scale of these upheavals.

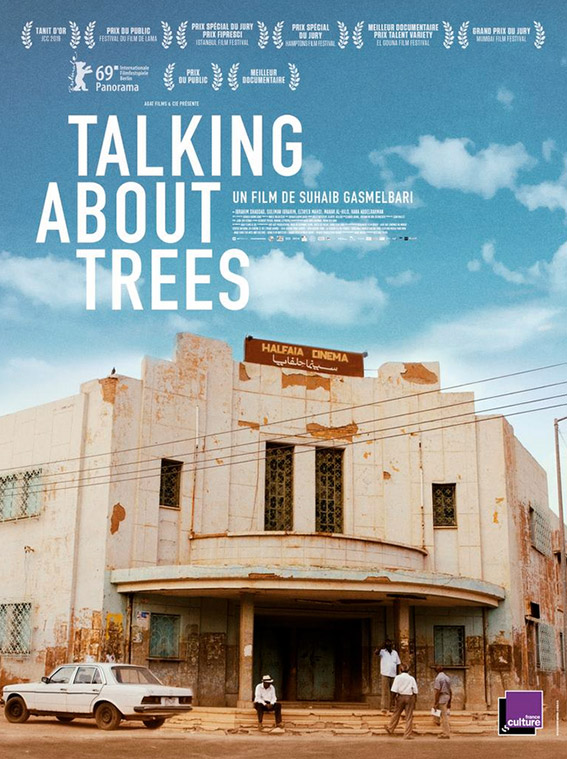

I’m sure I wasn’t alone, during the lonely nocturnal lows of lockdown, in feeling my mind unravel due to information overload, my spirits flag in the face of mounting daily death tolls, and my anger rise as the raw wounds of ancient injustices were reopened. Yesterday, I saw a car sticker that read: ‘Trust me, I’m even more f****d off than you are’. I doubt it. I’m f***d off by the cars and planes that are depressingly thick on the ground and in the air again, and with the idea that, for all the babble about building back better, people seem content to return to ‘business as usual’. While I was reviewing Suhaib Gasmelbari’s Talking About Trees during the last London Film Festival, the West End was locked down by Extinction Rebellion protests. I’d said how delightful it was to roam roads suddenly free of traffic. Little did I know, then, that within months those same roads, even the skies above them, would be emptied by the pandemic. We never know what’s around the corner.

The sound of chirruping, warbling birds, no longer buried beneath the metallic noise of cars, cheered me up during lockdown but there remained a void where barbers, bookshops, cinemas, libraries, swimming pools, and people had once been. Above all, like everyone else, I missed those I love. The closure of cinemas hit me hard, if less hard than I’d feared. Neither online events like the We Are One film festival nor the discovery of sites like archive.org compensated for what we’d lost: the immersive experience of darkened rooms and flickering shafts of light, the familiar spaces where we let ourselves unfold and weep, the communal thrill of shared delight.

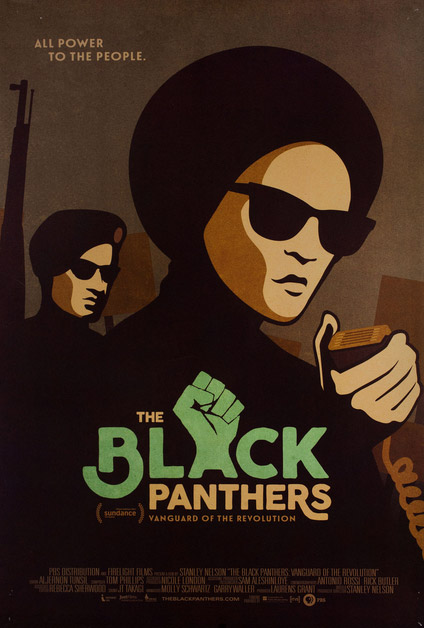

I reached for films like Santiago Álvarez’s Now, Howard Alk & Mike Gray’s The Murder of Fred Hampton, Göran Olson’s The Black Power Mixtape and Stanley Nelson’s The Black Panthers but the images captured by citizen journalists were a form of cinema like no other. There are scenes in Steve McQueen’s Twelve Years a Slave and Nate Parker’s The Birth of a Nation that burn themselves on the mind but the rage they provoke is as nothing to that induced by the footage of George Floyd’s murder. Not since the murder of Rodney King have images caught on mobile phones more graphically revealed and perfectly symbolised the evils of American racism. The battle cries of an earlier era echo down the decades: We’re all German Jews! The whole world’s watching!

My red mist has now cleared slightly, the dust has settled some, and it’s easier to see clearly, or at least more clearly than before, what’s been going down. The birdsong is plangent now but the bad news isn’t as relentless. In the dark times of lockdown there were occasional shafts of sunlight, notably the cheering, if also slightly alarming sight of people on the streets, raising the proud fist of solidarity and black power, sticking it to the man. Calmer, less twitchy, I feel ready to reflect and to learn. In an attempt to make sense of the confusing mess of the moment, if only for myself, I’ll rewind over recent events and recent history – with the help of a few of the books and films that also helped me through the dark times of lockdown.

In particular, I’ll take as my touchstone, Pandæmonium, the only book of Humphrey Jennings – the man who Lindsay Anderson described, in a Sight & Sound article of 1954, as ‘the only real poet the British Cinema has yet produced’. Danny Boyle, who drew on Pandæmonium for his spectacular opening ceremony of the 2012 Olympics, says, ‘When I first held this book in my hand, I swear I could feel it shaking with its own internal energy’. I know the feeling. The book has been called a modern history of Britain but Jennings himself modestly called it an ‘imaginative history of the Industrial Revolution’. ‘Neither the political history, nor the mechanical history, nor the social history nor the economic history’, he stressed, ‘but the imaginative history’. In her introduction to my copy, Jennings’ daughter Mary-Lou Jennings says,

‘My father’s method of working on Pandæmonium has been compared to Isaiah Berlin’s artist who hopped from subject to subject: the fox who has no continuity of thought and aesthetic approach, no evolution. I believe that although on the surface he gave the impression of being foxlike, my father was more like Berlin’s hedgehog: he might seem to be hopping about, but in fact he was in pursuit of one end: the purpose of the poet’.

Below, I’ll hop around like a spiky hedgehog. As my paws pad from from subject to subject, I’ll focus on two men, outsiders both, who were in the right place at the right time and produced era-defining work as a result: the novelist, playwright and broadcaster John Boynton Priestley and the novelist, publisher and filmmaker Peter Lorrimer Whitehead. I’ll zoom in on Priestley’s wartime broadcasts from London in the period between Dunkirk and the Battle of Britain, and Whitehead’s film The Fall, shot in New York between the assassinations of Dr. King and Bobby Kennedy.

It may seem perverse, provocative even, to address the pandemic and racism by focusing on two dead white men. Sadly, none of the women writers among Priestley’s contemporaries were allowed as close to the centre of events as he was, and both black and female filmmakers were even more excluded in Whitehead’s day than they are now. Priestley and Whitehead witnessed at close hand the pivotal global crises of 1940 and 1968 respectively. The seismic events of their times send salutary messages to ours and it might be instructive to eavesdrop as they compare notes in mid-Atlantic. History repeats itself. It has to as we seldom heed the wisdom it whispers in our ears. We’d do well to pin ‘em back.

Priestley was a defining voice during a time of unprecedented peril for the Free World and the drive for a ‘New Jerusalem’. Having fought in the First World War, he wanted to turn the clock back to the time before it all went wrong, as I will below, so it might be set right next time. Whitehead documented the sociocultural and political revolutions of the sixties as nobody else. He was close to the centre of events in 1968 and documented the moment when the Civil Rights movement and the New Left reached the limits of legal protest and shifted from protest to resistance and revolution. Priestley believed in circular not linear time so it seems appropriate to leap around in time. I’ll work back from the present to 1940, fast forward to 1968, and finish in the present. I’ll fan out from events close to home to the States, from the local to the global, in search of clues to how we might build back better, pausing along the way to consider the urgent questions of servitude, slavery, statuary, racial profiling, police brutality and the re-writing of history.

When the coronavirus pandemic first reached our shores, the government was slow to respond but quick to invoke the Dunkirk spirit. Sluggish though its reaction to mortal danger was, it moved swiftly to evoke the collective memory and myth of that seismic moment, in 1940, when the Nazis massed across the channel, Luftwaffe bombs rained down on a defiant people, and Britain stood alone in defence of democracy against fascist tyranny. The pandemic was framed as a national not a global crisis and we were urged to face it as one, in emulation of those whose courage and sacrifice contributed to Britain’s finest hour – those millions who, in George Orwell’s phrase, swung together ‘like a herd of cattle facing a wolf’. As I once said on this site, in a review of Ken Loach’s The Spirit of ’45, that sense of wartime solidarity manifested itself in a resounding vote, in ’45, for a more just and equitable post-war settlement that would keep the wolf of want from all doors. It led to the creation of the NHS, one of the great achievements of British Socialism, and, in a sense, to the fine health care workers on whom we’ve all relied of late. The essence of that historic vote was compacted in a wee story Priestley told his enraptured listeners on the 28th of July, 1940, as the Battle of Britain hotted-up:

‘It wouldn’t matter much if I were taken off the air, but it would matter a great deal . . . if these young men of the R.A.F. were taken off the air; and so I repeat my question – in return for their skill, devotion, endurance and self-sacrifice, what are we civilians prepared to do? And surely the answer is that the least we can do is to give our minds honestly, sincerely and without immediate self-interest, to the task of preparing a world really fit for them and their kind – to arrange for them a final ‘happy landing’. Don’t insult them by thinking they don’t care what sort of a world they’re fighting for. All the evidence contradicts that. And here’s a bit of it in a letter that reached me a day or two ago. It runs as follows:

“My son was formerly a salesman; he resigned in order to join the Air Force. On a recent visit home he said: ‘I’ll never go back to the old business life – that life of what I call the survival of the slickest; I now know a better way. Our lads in the R.A.F. would, and do, willingly give their lives for each other; the whole outlook of the force is one of ‘give’, not one of ‘get’. If to-morrow the war ended and I returned to business, I would need to sneak, lie, cheat and pry in order to get hold of orders which otherwise would have gone to one of my R.A.F. friends if one of them returned to commercial life with a competing firm. Instead of co-operating as we do in war, we would each use all the craft we possessed with which to confound each other. I will never do it.” – His father ends by saying: ‘You, sir, will be able to adorn this tale, it’s a true one, and I hope you will’. But I don’t think it needs any adorning’.

Dunkirk ©

Warner Brothers Entertainment UK Ltd

I don’t think it needs adorning either so I’ll simply pause to dip my flag in salute of those whose skill, devotion, endurance and self-sacrifice pulled us all, Boris Johnson included, through the worst of the pandemic. If Johnson had a heart, I’d remind him of the debt we all owe them. I’d also remind him that the heroes of national legend he evokes voted for socialism in 1945, for good governance and sensible planning to meet the needs of all – and for an end to the kind of cut-throat, jack’s-aboard, laissez-faire capitalism that had created mountains of human misery in the interwar years and has led to thousands of avoidable deaths in the past few months.

| Always Look to the Language |

|

Inviting unfavourable comparisons with those millions of national legend and that high-water mark of national unity might, at first glance, appear ill advised on the government’s part. Doubly foolish at a time when the nation is as divided as it was during the General Strike, is split down the middle by Brexit, and faces a quartering from resurgent local nationalisms. But this lethally inept, slippery eel of a government is adept at one thing: the manipulation of public opinion. During lockdown, it staggered shambolically on, lurching from one crisis to the next, as the body count rose and both its actions and inaction cost lives – all the while hiding behind its protective public relations shield. It shielded itself from public scrutiny, particularly, with its disingenuous mantra about ‘following the science’ (as its scientists accepted the estimates of unreliable models instead of the evidence emerging from other countries), its platitudinous babble about trusting to ‘British common sense’ (as it displayed little of this elusive quality itself), and its sly flattery about ‘the sacrifice of the British people’ (exacerbated by its incompetence and mixed messages). As Tony Hancock once said, ‘What a load of old rubbish... I have never heard such unadulterated codswallop in all my life’.

The codswallop kept coming. Politicians talked of ‘doubling down’ on problems that may or may not have ‘bottomed out’, of ‘drilling down’ on details that appeared to have eluded it, and of ‘ramping up’ solutions that may or may not lead to ‘levelling-up’. We, the sceptical citizenry, could be forgiven for thinking things were topsy-turvy and that they, the ruling class, were all upside down. Finally, the public was assured it was coming out of ‘national hibernation’ and that local spikes in coronavirus infections will be dealt with by a ‘whack-a-mole’ strategy. One trembles for democracy that such unsavoury slop was lapped up by so many and criticised by so few. Christopher Hitchens once warned us against those who employ the term ‘we’ or ‘us’ without permission. He considered it an insidious form of conscription and ‘an attempt to smuggle tribalism through the customs’. We need to watch our language! As his old sparring partner Noam Chomsky said, while unpacking the overused cliché about ‘speaking truth to power’, it’s always more useful to work from the premise that power generally knows the truth, but elects to hide it.

It is estimated that Luftwaffe attacks on British cities in the Blitz of 1940-41 cost about 40,000 civilian lives. The pandemic, and the government’s ramshackle response to it, have already cost many thousands more deaths than that. And this despite initial government statements that containing the death toll below 20,000 could be considered a ‘success’. Confusion now hath made his masterpiece... It a matter of record that the government’s initial strategy was based on the idea of ‘herd immunity’. Thankfully, that approach was soon abandoned. Unfortunately, its next steps were catastrophic. The government turned to face the challenge like an oil tanker with faulty engines. It is now public knowledge that it was fatally slow to impose a lockdown, slow to provide personal protective equipment, slow to quarantine incomers, and slow to implement the ‘test, track and treat’ systems that had saved lives elsewhere. As lockdown was lifted, the Prime Minister launched ‘Project Speed’, an FDR-lite ‘New Deal’ to help us to ‘build back better, greener and faster’ and – wait for it – to ‘double down on levelling up’. The recent record doesn’t fill one with confidence that this rhetorical emphasis on speed will translate into speedy action. Nor does a dishevelled Prime Minister who not only speaks in riddles and soundbites but also thinks in them inspire great confidence. Bored of imitating Churchill, he switched to imitating Roosevelt, but whatever disguise he dons after rummaging in the fancy dress basket of history, his limitations are there for all to see.

Such failures of good governance were compounded by problems arising from privatisation, an underfunded and unprepared NHS, cuts to local government finances that had intensified during the austerity period, and the wider inequalities of class and race that have deepened under the neo-liberalism. Outrageously, the Health Secretary spoke of ‘throwing a protective shield’ around care homes, at a time infected patients were still being released into them – without testing. Thousands of senior citizens, many of them veterans of ‘The People’s War’, have died in care homes during the pandemic. Public perceptions have changed in subtle, maybe deep-seated ways due to our collective admiration for those veterans, for the NHS, and for the health care workers we applauded each week during lockdown.

There was certainly an angry public reaction when the Prime Minister effectively blamed care homes for the problems his government’s incompetence created. That anger and shift in the public mood may yet translate into the same hunger for change that is coalescing behind the Black Lives Matter movement. The UK and the US, cheerleaders of consumer capitalism, have signally failed to protect their populations from the pandemic. The mask has slipped and it’ll take more than ‘a chicken in every pot and two cars in every garage’ to patch things up. The politics of hope is on the move again and history tells us no society remains unchanged by a pandemic.

The pandemic and the Black Lives Matter movement have revivified arguments against inequality and racism, neo-colonialism and nationalism, economic and cultural imperialism, and, yes, capitalism. The interventionist, mock-Keynesian use of the public purse by nation states has called the spurious claims of rapacious, doctrinaire neo-liberalism into question. No finger-wagging talk in high places, now, of ‘the magic money tree’, ‘lame duck industries’, ‘fiscal rectitude’ or ‘trusting to the market’. All this might have amounted to an argument for socialism, if the government weren’t operating like a seedy venture capitalist investing public money badly: ring-fencing buy-to-let landlords, at the expense of renters, to prop up property markets; giving freely to ‘zombie’ transnationals, like fragile or failing car and airline companies, without regard for the environmental cost; and saddling future generations with debt with no regard for the social costs. Credit where credit is due, though, they’ve agreed to fund the NHS properly. The icing on the cake of this latest volte-face would’ve been a heartfelt apology but this government doesn’t apologise. It has no conscience. It simply buckled under popular pressure – much like the swivel-eyed businesses that pay lip service to the concerns of anti-racists and eco-activists while keeping a beady eye on their pockets in order to pick them. But enough already of the gang in government, time to consider the national myths they trade on.

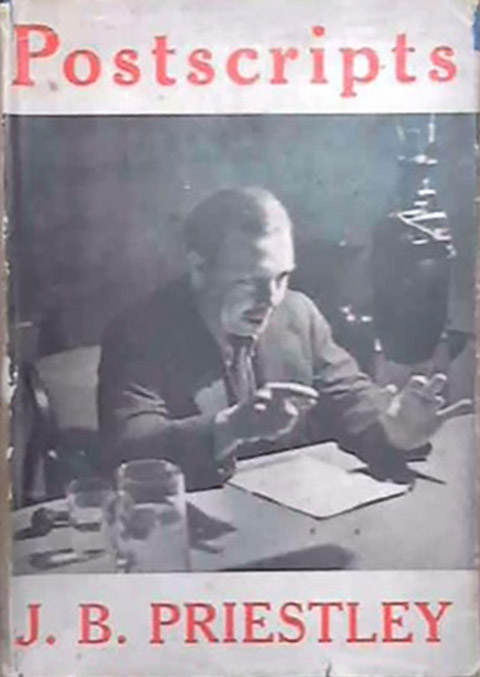

A couple of years ago, I was delighted to discover, abandoned and forlorn on the dusty shelves of a charity shop, a tatty 1941 reprint copy of J.B. Priestley’s Postcripts. The book contains transcripts of Priestley’s hugely popular BBC broadcasts of 1940 - in which he created, among other things, the myth of the Dunkirk spirit and the ‘little boats’ that helped sail the bruised remnants of the British Expeditionary Force to safety. That slim volume immediately became my favourite book and one of my most cherished possessions. I can’t read it without welling up. Sadly, I lost it on the Underground while heading home, weary and despondent, one wintry night but – joy of joys! - I stumbled across it again, with even greater delight, online last week. It sits next to me as I write, the exact same copy I lost - with its distinctively foxed, sun-bleached spine and stained cover, and the imperishable words ‘Dorothy Tweeddale’ inscribed within, in the elegant penmanship of a bygone era.

I marvel at the wee miracle of that book’s journey back to me, like a homing pigeon or, better say, like one of the little boats returning home to England from Dunkirk. There’s a Priestley touch to the story. I think he’d have liked it. Perhaps because of the experience of being buried alive in the trenches during the First World War, perhaps because of the sense of déjà vu he experience at the advent of the Second World War, Priestley was interested in Jung’s ideas on synchronicity and believed in ‘serialism’ – roughly, the proposition that what goes around comes around, that we live our lives over and over – with the opportunity to learn from past mistakes. In the first of his broadcasts, Priestley spoke openly about the mistakes and miscalculations that lead to disaster at Dunkirk. ‘We have gone sadly wrong like this before; and here and now we must resolve never, never to do it again. Another such blunder may not be forgiven us’. As an old solider who’d seen the mayhem caused by disastrous leadership, he may have been thinking about Gallipoli or ‘homes for heroes’. If he’s looking down on our times, he must be thinking, ‘here we go again’.

That first Postcripts recording was broadcast in June, 1940 – just after Churchill’s ‘We shall fight them on the beaches’ speech, just before publication of ‘The Guilty Men’, the bestselling critique of pre-war government failures. The broadcast illustrates Priestley’s knack of drawing symbolic meaning from tiny detail. In it, one little boat lost at Dunkirk stands in for the wider fight of the little people, and the collective resistance to encroaching tyranny that he himself embodied. Priestley says: ‘I tell you, we were proud of the “Gracie Fields”, for she was the glittering queen of our local line... and never again will we board her at Cowes... she has paddled and churned away – for ever. But now, look, this little steamer, like all her brave and battered sisters, is immortal. She’ll go sailing proudly down the years in the epic of Dunkirk. And our great grand-children, when they learn how we began this war by snatching glory out of defeat, and then swept on to victory, may also learn how the little holiday steamers made an excursion to hell and came back glorious’.

Priestley’s optimism and lyricism went down a storm. It’s easy to see why he was so huge popular in 1940 and why, as surely as Churchill, he became synonymous with the spirit of defiant solidarity that characterised that period of the war. His warm working-class vowels and light touch, chatty delivery and plain speaking, willingness to face facts and grasp of popular opinion won hearts and minds. Unlike Churchill, the government censors and the largely pliant press corps, he also trusted the citizenry. Unlike Churchill, who invoked centuries of history, he looked to the future and ‘a nobler world in which ordinary, decent folk can not only find justice and security but also beauty and delight’. Priestley’s no-nonsense, straight-talking north-country candour was clearly just the thing for folk fed up with the status quo and patrician propaganda, a little tired of Churchillian bluster and possessed, like Priestley himself, of what Orwell called ‘a power of facing unpleasant facts’.

In their ‘darkest hour’, people wanted the truth, unvarnished, and they weren’t about to find them on the BBC, whose view of audience outreach relied on happy-go-lucky entertainers like Flanagan & Allen, George Formby and Gracie Fields. Priestley earned the nickname ‘Jolly Jack’ due to his mock-crabby comic timing. His broadcasts were highly polished miniature works of art, and he could bluster with the best of em, but he gave his audiences the information they craved. Perhaps more importantly, he gave them the same sense of hope and togetherness that had seeped out of his bestselling novel The Good Companions. He helped forge the spirit of solidarity, mutual respect and collective strength that culminated in the Labour Party's unprecedented landslide victory of 1945. When the spectral police officer of his 1945 play An Inspector Calls, says, ‘We don’t live alone. We are members of one body. We are responsible for each other’, he might have been talking about the pandemic or, indeed, defending the National Health Service.

The Postcripts programmes were commissioned by the BBC to counter the alarmingly large audience garnered by William Joyce, a.k.a. Lord Haw-Haw. Before Priestley replaced Maurice Healy at the microphone over a third of radio audiences had been tuning into Joyce’s ‘Germany Calling’ Reichsrundfunk broadcasts. They did so not because fascism had widespread appeal but, primarily, in search of the information the Ministry of Information withheld – censored facts, for instance, about the bombing of Coventry, Glasgow, Liverpool, et al. In his book Nazi Wireless Propaganda, Martin Doherty says Priestley was mobilised by the BBC to challenge the picture Lord Haw-Haw painted of a plutocratic England ‘where people are misled by corrupt and irresponsible leaders, where the small wealthy class leaves the masses to misery, unemployment, hunger and exploitation; of an Empire built on brutality and rapacity, now as decadent and as divided as its Mother Country; of an England hated by the world for her selfishness and ruthlessness’.

Priestley largely shared that view. He called England ‘a plutocracy roughly disguised as an aristocracy’. In his 1933 travelogue English Journey, which prompted Orwell’s Wigan journey and foreshadowed the Mass Observation and Documentary movements, Priestley lambasted the self-centred, self-satisfied business class who forced workers to live ‘like black-beetles at the back of the kitchen stove’. He’d long despised the ruling class, though, for what it’d done to his comrades in the trenches during the First World War and to the people in the Hungry Thirties. In his 1960 autobiography Margin Released, he says: ‘The tradition of an officer class, defying both imagination and common sense, killed most of my friends as surely as if those cavalry generals had come of the chateaux with polo mallets and beaten their brains out’.

The battle of the airwaves between Joyce and Priestley was a struggle between Received Pronunciation (the de facto prestige accent of the day) and Proletarian Vernacular (in Priestley’s case a West Riding burr), but also one between competing visions of the world the war would win and between two different kinds of the same racism. I mention Priestley not only because he helped create the national mythology so shamelessly exploited by the parcel of rogues currently in charge of our affairs, but also because his casual racism begs questions about cancel culture. When he spoke of Britain, he meant England. He had little time for the Celts and none for the Irish. That was true of most of his contemporaries, including George Orwell. Racism takes many forms and we must challenge it where we meet it.

Anti-Irish racism has been a staple of British life down centuries and was echoed in the USA by the Know-Nothing movement and the Ku Klux Klan. It would turn even more venomous in Britain after the IRA’s Sabotage Campaign of 1939-40 - of which Simon Donnelly said, ‘We want the enemy, who has kept our people in bondage for 700 years and who continues to pour insults on us, to be pitilessly vanquished’. That racism flared up, more recently, when the republican movement again extended its campaign to the mainland in the 1970’s and was a contributory factor in the false imprisonment of the Guildford Four, the Maguire Seven and the Birmingham Six.

William Joyce’s anti-Irish racism flowed not from a backlash against contemporary Irish resistance but from the Loyalist Ascendancy mind-set he inherited from his father. As with most forms of racism, it combined superiority and inferiority complexes, uniting in him a disgusted sense of superiority in relation to his Irish peers and an inferiority complex in relation to his English paymasters. Joyce joined the barbaric Black and Tans at fifteen, and the British Union of Fascists as soon as his flirtation with the Conservative Party proved a career dead end. In The Meaning of Treason, Rebecca West notes that Oswald Mosley offered him ‘the hope that under fascism, England might be what Ireland had been to him and his family before there was Home Rule: a police state where spruce tyrants held down the unworthy and rewarded those who submitted to them’.

If Joyce’s racism is understandable or, at least, unsurprising, it seems astonishing that Orwell and Priestley, two writers so generally forensic in their examination of the politics of their day, should have so little to say about the Irish question. Re-visiting his native Bradford for English Journey, Priestly described the ‘Wool City’ as ‘at once one of the most provincial and at the same time one of the most cosmopolitan of English provisional cities’. A similar contradiction permeated his conflicted self. Elsewhere in the book, he says: ‘The England admired throughout the world is the England that keeps open house ... History shows us that the countries that have opened their doors have gained’. Neither Priestley nor England extended much warm hospitality to the Irish. Discussing the impoverished Liverpool Irish, Priestly says: ‘The Irishman in England cuts a very miserable figure ... the English of this class generally make some attempt to live as decently as they can under these conditions ... however, the Irish appear in general never even to have tried; they have settled in the nearest poor quarter and turned it into a slum or, finding a slum, have promptly settled, to out-slum it’. Priestly concludes, ‘If we do have an Irish Republic as our neighbour, and it is found possible to return her exiled citizens, what a grand clearance there will be . . . what a fine exit of ignorance and dirt and drunkenness and disease’. Racist statements such as that take the breath away and are all the more shocking for being commonplace. The origins of successive waves of immigrants may change but the racist impulse remains the same, as we’ll see below.

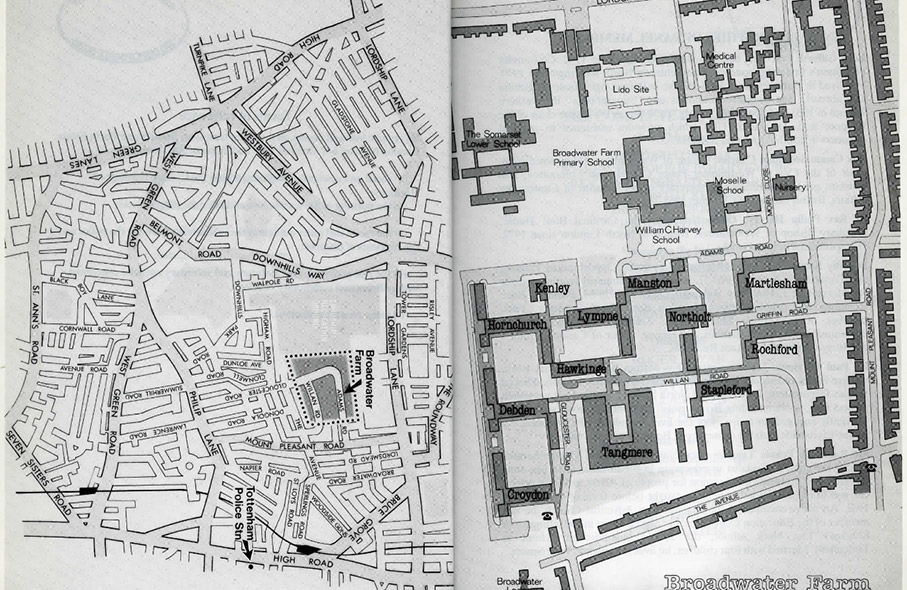

In the mid-1980’s, I lived off Black Boy Lane in Tottenham, a short walk from the Broadwater Farm Estate. The area is criss-crossed with neat rows of Edwardian and Victorian houses, amid which The Farm, with its blocks named after Second World War RAF aerodromes, stands out like a sore thumb. I confess, I liked the place, especially in summer, but then I didn’t have to live there. A high-density sink estate on stilts with dark, dank corners and linked aerial walkways, it was a bleak and intimidating place back then. Faulty lifts, damp flats, stained concrete, and cockroach infestations were the least of the estate’s problem. The Farm was feared by the police (who were regularly pelted from above), detested by residents (who couldn’t wait to leave), and regularly described as the worst place to live in England. The estate certainly felt forbidding during riot that erupted there in the autumn of 1985.

The ‘disturbances’, during which PC Keith Blakelock was killed, were ignited by the death of a black woman, Cynthia Jarrett – during a police raid in Stamford Hill. They were bound up with the rioting in Brixton that’d been sparked off, a week earlier, by the police shooting of another black woman – Dorothy ‘Cherry’ Groce – in her bed, as her children slept close by. The community had been under heavy manners for some time: the hated stop-and-search ‘sus’ laws had been repealed after the 1981 riots but stop-and-search practices were still being brutally applied, particularly by the Met’s SPG hit squads. Local unemployment stood at about 40 per cent and was way higher on the Farm. The dynamics of degeneration and deprivation were shaking down on the streets. Racist harassment was commonplace and people had had enough long before the Cherry Groce and Cynthia Jarrett incidents. The police brought matters to a head, on the night of the riot, by cordoning off the estate, effectively kettling residents without cause. The whole affair felt like a repeat of the infamous events at Orgreave of the previous year, when the police corralled striking miners in a field, charged them on horseback, and gave them ‘a bloody good hiding’.

Nobody I knew in the area was too surprised when the pent-up anger exploded in rioting on the night of 6 October 1985. Nobody seemed surprised, either, that the establishment’s kneejerk response to the riot was to delegitimize the community’s anger and denigrate those dying disproportionately at the hands of the police, disproportionately affected by unemployment, harassed and imprisoned. There was a hideous inevitability about all that followed after the riots: the TV crews that came and went; the journalists parachuted in to talk of ‘mob violence’ and ‘the collapse of law and order’; the calls for inquiries; the cover-ups; the saturation policing; the insistence that ‘lessons must be learned’. I learnt what it must feel like to live in a police state. I learned this too: it’s one thing to be unjustly harassed by the police, day-in-day-out, but another thing to lie awake, sleepless, for fear your front door might be kicked in; another again to fear you might be killed in bed. A person’s liable to snap and when the pressure builds the lid’s likely to fly off.

Six suspects were charged with the murder of Keith Blakelock. Three young lads were almost immediately acquitted after it was found that they’d been questioned under duress, naked and without accompanying guardians. Three others were charged with murder in 1987 but subsequently acquitted in 1991. In the wake of the riot, two Tory MPs, Oliver Letwin and Hatley Booth, sent a profoundly racist memo to Margaret Thatcher advising her not to spend money on urban regeneration or job creation schemes. Any money offered to black entrepreneurs would, they said, be wasted, as they’d only ‘set up in the disco and drug trades’.

In an echo of J.B. Priestley’s comments on the Irish, Letwin and Booth said: ‘The root of social malaise is not poor housing, or youth “alienation”, or the lack of a middle class. Lower-class, unemployed white people lived for years in appalling slums without a breakdown of public order on anything like the present scale ... Riots, criminality and social disintegration are caused solely by individual characters and attitudes. So long as bad moral attitudes remain, all efforts to improve the inner cities will founder.’ In 1994, Hartley Booth resigned his government position after a Westminster sex scandal. In 2015, Letwin apologised ‘unreservedly’ for the memo.

| The Violence of the State |

|

In 1983, her contribution to the anthology Over Our Dead Bodies: Women Against the Bom, Dorothy ‘Dot’ Thompson said, ‘We must take back the language of freedom and the practices of democracy from the people who are perverting them. Who but ourselves can defend us against these defenders? Their policies impoverish us materially and oppress us politically. We have to take our country back, and defend it in our own way’. Another great historian, Sheila Rowbotham, described the essay as a plea for tolerance and democracy in which ‘Every one of us is involved’.

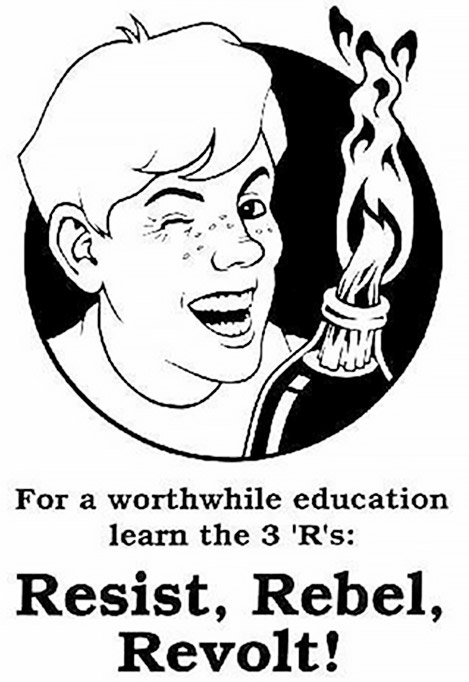

Torching cars wouldn’t have been high on Dot Thompson’s list of strategic responses to crises but then, as far as I’m aware, she never lived on the Broadwater Farm Estate, was subject to stop-and-search policing, or had her front doors kicked in at night. Which is merely a crude way of saying social circumstances shape human responses to them. Try, social-distancing in a favela, slum or shanty town. In Over Our Dead Bodies, Thompson echoed Juvenal but also, unwittingly, the above-mentioned white indentured servants and black slaves, the Black Panthers and Irish Republicans, the Anti-Apartheid and Viet Cong freedom fighters - all those who saw self-defence as an essential means of protecting their communities, a component of resistance, and a first step to liberation. Tolerance and democracy have their limits, as Nazi Germany, Pinochet’s Chile, and Trump’s America, for instance, have taught us. We know that the violence of the police is very often disproportionate to the crime contained but few see the violence of those who protest against it as a proportionate response. A Molotov cocktail, it might be said, is not a proportionate response to the violence of the gallows and government, the stake and the state.

I was just a naïve kid at the time of the Broadwater Farm riot, a white ‘ally’ from the local poly, deep sea leagues out of my depth on the night. The police treatment of protesters on the High Road in the afternoon was par for the course: it was aggressive, ‘heavy-handed’ and racist but I’d seen worse at football grounds. The visceral ferocity of the later violence on and around The Farm was something else. The police surrounded the Farm in massed ranks. They seemed intent on settling scores but then so did the local lads I knew. My memories of that night are hazy, partly as I’d psyched myself up with beer, but I remember bricks descending from skies ablaze with orange fire. I also remember thinking that somebody was going to die and deciding it wasn’t going to be me. Anthony Gifford, who chaired the subsequent inquiry into the riot expressed concern ‘with the increased militarism of the police’. Looking back, I see their truncheons, rows of plastic shields, and battle dress of blue dungarees and it seems positively quaint.

I’d witnessed racism at first hand as a boy in Africa and as a teenager in the Arab World and I recognised it immediately when I saw it back home. I’d also read Orwell’s Homage to Catalonia and already knew what he meant when he said, ‘When I see an actual flesh-and-blood worker in conflict with his natural enemy, the policeman, I do not have to ask myself which side I am on’. I instinctively knew which side I was on, but I hadn’t experienced police brutality or felt the burning anger against it burning my insides. Neither had most Britons, which is one of the reasons the country was substantially more outraged by the death of PC Keith Blakelock than it was by the deaths of the Cherry Groce and Cynthia Jarrett. The language of the unheard is hard to translate and, as Dr. King said in 1967, ‘large segment of white society are more concerned about tranquillity and the status quo than about justice, equality and humanity’. The violence of the state isn’t merely a matter of police brutality and political repression. As Bobby Kennedy said in a speech delivered a day after Dr. King’s assassination, a couple of months before his own:

‘ ... there is another kind of violence, slower but just as deadly, destructive as the shot or the bomb in the night. This is the violence of institutions; indifference and inaction and slow decay. This is the violence that afflicts the poor, that poisons relations between men because their skin has different colours. This is the slow destruction of a child by hunger, and schools without books and homes without heat in the winter’.

A healthy society would be delighted to ‘defund the police’ in order to focus on crime prevention. A preventative policing policy would redistribute resources to eradicate the deprivation, insecurity and inequality that drives crime. A healthy society would brag proudly about reducing police numbers not boast of increasing them. The fewer police were needed, the logic of the argument would run, the fewer problems of criminality and lawlessness there must be. An unhealthy society hollows out civic and public life and then wonders why people behave selfishly and criminally. Last week, the Guardian published a piece by Nick Pettigrew – a retired anti-social behaviour officer. He begins by sketching what an ASB officer isn’t: not an addiction counsellor, fire safety officer, housing officer, police officer, social worker, solicitor or mental health worker. An ASB officer is ‘a tiny bit of all of the above’. He left his job as it was dragging him into addiction and depression. Mr. Pettigrew says:

‘There are so many things that society is getting wrong that all affect how well somebody like me can do the job I do – or rather, did. There are more people who need social housing than there are homes to put them in. We’re also missing the dozens of little knots that held the safety net together but have been austeritied out of existence: libraries, Sure Start schemes, youth centres, and hundreds of services that couldn’t turn a profit but helped to keep this country a cohesive society, rather than a collection of terrified individuals wondering when their world is going to collapse and who they can blame when it does’.*

The police would, I’m sure, prefer to chase criminals than stand on the frontline of a society gone wrong, as Nick Pettigrew once did. Too much is asked of them, as too much was asked of Nick Pettigrew. The police are also being asked to be social workers, mental health workers, and so forth. Dixon of Dock Green might have asked George Floyd if he required any assistance or needed directions. Today’s police are built of sterner stuff. They have to be. The resilient, residual decency of the common citizen remains largely intact, against all odds, but a society that glorifies greed as a cardinal social virtue, one based on selfish competition, inevitably brings out the worst in many. The worst have got worse, and they’re a handful. The ‘bobby on the beat’ of J.B. Priestley’s era is a distant memory because the high standards of collective decency and social justice of his era are a distant memory too.

Priestley was a pioneer of working class representation in public life, a democrat who refused shiny honours, a figure second only to Churchill in uniting people against fascism, a leading voice in the concerted collective push for a fairer post-war world – but he also shared Lord Haw-Haw’s anti-Irish views. And here’s the rub: does that loathing of the Irish, which Priestley shared with millions of his contemporaries and compatriots, invalidate his work? Does it urge us to lasso the statue erected in his honour in the heart of Bradford and tear it down? If one follows the logic of the Black Lives Matter movement, it is difficult to know where to draw the line or, better say, to know whether one would want to draw the line.

There are, thankfully, no statues to William Joyce in Berlin but Treptower Park contains the colossal Soviet War Memorial, the largest monument in Germany. It was constructed to honour the Red Army troops who liberated Berlin in 1945 and doubles as a cemetery to 7,000 of them. Should the Soviet Memorial be dismantled because it contains quotes by Stalin and is adorned by the discredited hammer and sickle? In 1994, a few years after the USSR collapsed, my old tutor Laura Mulvey and Mark Lewis made a film for Channel 4 called Disgraced Monuments. It considers the fate of toppled Soviet statues, repeats the argument that history repeats itself, and contains a stark warning about the dangers of playing fast and loose with granite and marble excretions of the past.

Discraced Monements (Laura Mulvey, Mark Lewis 1994)

In the same charity shop in which I’d found Priestley’s Postcripts, I recently bought an extraordinarily odd book called Lenin On Literature and Art. Snippets of text (in a range of mismatching fonts) and random images (bearing no relation to the text) have been glued into it. In a section on monuments, a revolutionary edict of 1918 is reproduced: ‘The monuments erected in honour of tsars and their minions are to be removed from the squares and streets and stored up or used for utilitarian purposes’. Also reproduced is an approved list of those to whom statues are to be erected. St Petersburg became Petrograd in 1911, Leningrad in 1924, and St Petersburg again in 1991. The imperial city of Tsaritsyn became Stalingrad in 1925 and Volgograd in 1961. In 2017, during the period of ‘decommunization’, the Ukraine removed all but two of the 1322 statues of Lenin in the country. The names of cities, streets and squares change like the seasons. Statues rise and fall like governments, nations and empires. Attitudes and language change too and future generations may look askance at us if we burn books, censor films, and topple statues at will.

Few would argue against removal of the statues of slave traders, colonialists and imperialists that litter the land – not even those, like Simon Schama and I, who urge caution and think museums the best places for them. Similarly, it would’ve been a retrograde step had HBO banned Gone With the Wind but a positive development that they’ve acknowledged pulsating anti-racist passions by pressing pause, with a view to showing it later with a contextualising introduction. Explicitly racist films like D.W. Griffiths’ The Birth of a Nation should only be seen with such contextualizing introductions or in circumstances where debate is encouraged.

But is context all? Is there a case for banning Nate Parker’s Nat Turner film The Birth of a Nation because of the director’s personal behaviour? Take three of the great novels of the 20th Century. Should we burn Francis Stuart’s Black List, Section H because its author broadcast Nazi propaganda? Should Arthur Koestler’s Darkness at Noon be burned because its author was a serial rapist? Should Celine’s Journey to the End of the Night be burned because its author was an anti-Semite? Who judges the judges? The question of statues is as fraught as that of banning films or burning books but challenging their presence need not and should not entail erasure of the past. The complexities of history, and of human behaviour are such that a tolerant, respectful attention to detail and nuance seems sensible. Simon Weil felt that ‘attention is the rarest and purest form of generosity’. Let’s be generous and pop statues of slavers in museums not tip them into harbours – tempting, oh so tempting and satisfying though that may be – and consider slavery in the round.

In 1687, the Irish naturalist Hans Sloane, after whom Sloane Square is named, travelled to Jamaica as physician to the island’s Governor, not long after the English had driven the Spanish from the island. While in the Caribbean, he furthered his work for The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge. In 1770, in the first of two published volumes of his findings, Sloane also reported on the treatment of slaves. He says: ‘The punishments for crimes of slaves are usually for rebellions; burning them, by nailing them down on the ground with crooked sticks on every limb, and then applying the fire by degrees from the feet and hands, burning them gradually up to the head, wherein their pains are extravagant. For crimes of a lesser nature, gelding, or chopping off half of the foot with an axe . . . For negligence, they are usually whipped by their overseers . . . After they are whipped until they are raw, some put on their skins pepper and salt to make them smart; at other times their masters will pour wax on their skins, and use several very exquisite torments’.

When faced with such sickening reminders of racism and the human capacity for cruelty, it’s hard to be generous about history or statues. It’s worth remembering, though, that white slaves, called indentured bondservants, fared little better. In her 1922 book Where the Twain Meet, the Australian travel writer Mary Gaunt quotes Hans Sloane extensively and calls him the ‘first historian of Jamaica’. We must treat her claim that white servants were treated worse than black slaves with the same scepticism we greet Sloane’s claim that slaves were treated worse by their own kind than the English, but the hideous suffering of neither servants nor slaves should be forgotten. Gaunt says the first of the indentured servants were 1,000 Irishmen and 1,000 Irishwomen sent there as political prisoners by Cromwell in 1660, under the lash of the cat o’ nine tails. Such was the value placed on human heads (£40 for an artisan, £20 for an ordinary labourer, £10 for a carpenter) that later arrivals had often been kidnapped, press ganged or stolen from Spanish slavers before being sold at market and worked to early graves. Gaunt mourns their passing:

‘Once they were landed, roystering cavaliers and prim roundheads crowded to the ship and the servants passed before them and were examined, men and women alike, as if they had been so many horses or cattle ... the higher the rank a man had held in England, the lower would be his value in Jamaica ... All authorities agree that these bondservants were cruelly ill-used. It was generally understood that while a man looked after his black slave, who was his for life, it was in his interest to get as much as he could out of his bond-servant, whose services were his only for a limited period . . . They were simply bond-servants on whom no one wasted pity ... All trace of them is lost’.

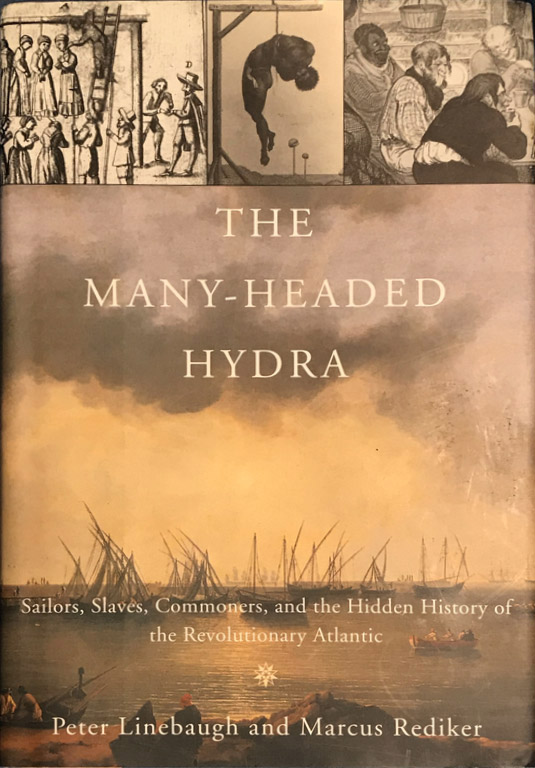

I’m conscious that mention of those forgotten wretched souls might raise eyebrows. I mention them not to reprise the argument, racist in the extreme in this charged moment, that ‘All Lives Matter’ or, worse still, ‘White Lives Matter’. The principles of the Black Lives Matter movement are implicitly inclusive. They insist plainly that black lives ought to matter while reminding us that, to too many whites, they all too often don’t. Nor do I mention the Irish, as I might as easily have mentioned the Chinese or any other subject race, as precursor to an argument that revolutionary movements must always brace themselves against the inevitable reactionary backlash. Nor, even, to remind the reader, as Kevin Bales does in this book Disposable People, that more than 27 million people are enslaved, NOW - more than all the people stolen from Africa during the transatlantic slave trade. I mentioned the forgotten servants to insist on the solidarities that cut across race and national boundaries – as Peter Linebaugh and Marcus Rediker do in their magisterial ‘hidden history of the revolutionary Atlantic’, The Many-Headed Hydra.

Linbaugh and Rediker say: ‘From the beginning of English colonial expansion in the early seventeenth century through the metropolitan industrialization of the early nineteenth, rulers referred to the Hercules-hydra myth to describe the difficulty of imposing order on increasingly global systems of labour. They variously designated dispossessed commoners, transported felons, indentured servants, religious radicals, pirates, urban labourers, soldiers, sailors and African slaves as the numerous, ever-changing heads of the monster ... the heads, though originally brought into productive combination by their Herculean rulers, soon developed among themselves new forms of cooperation against those rulers, from mutinies and strikes, to riots and insurrections and revolution’.

The hydra myth, Linbaugh and Redicker say, ‘expressed the fear and justified the violence of the ruling class, helping them build a new order of conquest and expropriation, of gallows and executioners, of plantations, ships and factories’. In their counter-history of a multi-ethnic class composed of ‘the outcasts of the nations of the world’, they reclaim the hydra myth as a means of ‘exploring multiplicity, movement and connection, the long waves and planetary currents of humanity’. As a means, also of reviving a hidden history in which the radical ideas of the English Revolution (of the Putney debates, the Diggers and Levellers) sailed the high seas, took root on land, and inspired first the multiracial rebellions of indentured servants, later the revolts of black slaves from Africa and ‘Indian’ slaves from Florida; first the French revolution and then the American revolution.

Linebaugh and Rediker point out that that history was hidden by repression – ‘by the violence of the stake, the chopping block, the gallows and the shackles of a ship’s dark hold’. It has also been hidden by an army of reactionary rah-rah historians who peddle the dominant, snake-oil narrative composed of dukes and duchesses, kings and queens, military victors and trading conquistadors, the benevolent nation state and the jolly old days of empire. Such historiographic humbug long ago linked arms with Heritage culture and rushed headlong into the vacuum created by the collapse of empire, Britain’s decline as a global power, and the disintegration of safe white, right-wing notions of national identity further threatened by increased racial diversity. Taken together, the purveyors of such popular history-lite present a picture of the nation and its people’s that underpins systematic racism.

That deranged, sterilised version of our proud and disreputable past expunges all dissent, discord, division and diversity from the record; dresses history in bonnets, bows, cravats and top hats; and presents itself as the only accurate account of the nation’s more complicated and complicit yesterdays. It points to a spectacular failure of imagination on the part of commissioning editors, producers and programmers. It purges the past of the political conflicts that shaped us as a people and a society. In doing so, it also circumscribes our futures. This recidivist culture cancels competing versions of national identity and shapes the systematic racism currently being challenged as never before. As Hugh Trevor-Roper once said: ‘History is not merely what happened; it is what happened in the context of what might have happened’.

Discussing the Black Lives Matter movement in The Critic, one of the worst offenders, the now discredited and disgraced David Starkey caricatured the contest of ideas over statues as a form of class struggle: ‘hoity-toity, woke middle-class miss bossy-boots versus a bunch of nice working-class lads’. Churchill’s statue, the cenotaph and the Union flag, he argued, are the central symbols of the nation. More surprisingly, he described the Black Lives Matter movement as ‘a peculiar perversion of Puritanism’. Delete the malice and there’s some truth in the comparison. The Black Lives Matter movement recalls the iconoclasm of the New Model Army. As historians such as Christopher Hill, E.P. Thompson and C.L.R. James demonstrated, the Putney debates revealed the radical wing of Puritanism and the New Model Army to be abolitionist. The Diggers and the Levellers – men like Colonel Thomas Rainsborough, Lt-Colonel John Lilburne and non-combatant Gerrard Winstanley – fought against slavery as much as against enclosure, impressment, poverty, private property, and the death penalty.

Winstanley viewed the earth as a common treasury for all. Rainsborough said, ‘Either poverty must use democracy to destroy the power of property, or property, in fear of poverty, will destroy democracy’. Nye Bevan often quoted Rainsborough. Soon after he had created the NHS, he wrote his only book, In Place of Fear. In its opening chapter, ‘Poverty, Property and Democracy’, he defined the central question of Tory politics: ‘How can wealth persuade poverty to use its political freedom to keep wealth in power?’ In the same book, Bevan says: ‘Revolution is almost always reform postponed too long. A civilised society is one that can assimilate radical reforms while maintaining its essential stability. The real enemies of society are those who use popular slogans to deflect the attention of the masses from an objective study of the social and political questions of the day’.

Now, as the shibboleths of recent times and statues of earlier epochs are challenged by a new generation of activists, we might think about who we honour instead of the slave traders, colonialists, imperialists and monarchs of yesteryear. The statues of savages and tyrants should come down and be confined to quarters in museums – as the statue of Edward Colston will soon be, red paint and all. Statues have traditionally been imposed upon landscapes, plinths and peoples from above. They’ve seldom been put in place as concrete expressions of the popular will. Perhaps there’d be support for a statue of Nye Bevan on Trafalgar Square or Parliament Square; at its base, two just words: ‘Our Nye’. Perhaps it could sit next to statues honouring black Britons such as, say, Olaudah Equiano, Stuart Hall or Darcus Howe; perhaps, if we were determined to be actively anti-racist, commemorating victims of British racism such as Cherry Groce, Cynthia Jarrett or Stephen Lawrence.

The Stuart Hall Project (John Akomfrah, 2007)

Mark Duggan grew up on the Broadwater Farm Estate. If I’d passed him on the street when I lived nearby, I doubt I’d have given him a second glance as he’d only have been three or four in 1985. As he grew up, he’d have seen incremental improvements to living conditions on the Farm and in Tottenham as a whole. In 2011, he was shot dead by police, a victim of racial profiling. The riots that followed spread from Tottenham, through London and then to cities across the country, just as they’d done in 1985. Lessons clearly had not been learned. It is irrelevant whether Mark Duggan was or was not a criminal; unimportant whether you side with crime, as Jean Genet did, or with ‘the forces of law and order’; accept or reject the argument that society prepares the crime and the criminal merely commits it; agree or disagree with Brecht’s assertion that the crime of robbing a bank is as nothing next to the crime of founding one. It is relevant whether or not Duggan was armed at the time of his death. He wasn’t. It’s also relevant whether or not the police leaked claims that Duggan had fired first or not. They did. The Independent Police Complaints Commission apologised to Mark Duggan’s family for false information fed to the media. No police officer was ever charged for Duggan’s death but Tony Hanley, a Police Firearms Specialist who blamed himself for it and claimed he kept seeing Duggan’s ghost, committed ‘suicide by cop’ – during a police raid.

Justice takes a long time coming and often doesn’t arrive at all. The Scarman Report into the causes of the 1981 Brixton riot blamed police stop and search tactics. The Gifford Inquiry into the causes of the Broadwater Farm riot criticised racist police and police tactics on the night. It wasn’t until 2014 that the Metropolitan Police apologised ‘unreservedly’ for the shooting – during a police raid – that had left Cherry Groce paralysed until her death in 2011. Racial profiling and stop-and-search police practices were in the news again recently. The athlete Bianca Williams and her partner were stopped, dragged out of their car, and questioned. The athlete Lyford Christie asked, ‘Was it the car that was suspicious or the black family in it?’

Last week, a police officer was suspended for kneeling on the neck of an unnamed black man during an arrest in North London. If miscarriages of justice and riots are to be avoided, racist police must be weeded out along with the socialised machismo and warrior cop mind-set they embody. More importantly, the systematic racism that underpins such events has to be rooted out. Society needs to look within. We all need to look within; but nowhere more so than in the USA. By way of a bridge for our crossing of the Atlantic, here’s the opening paragraph of Paul Beatty’s deliberately and delightfully offensive satire on race, The Sellout, highlighting racial profiling and unconscious bias:

‘This may be hard to believe, coming from a black man, but I’ve never stolen anything. Never cheated on my taxes or at cards. Never snuck into the movies or failed to give back the extra change to a drugstore cashier indifferent to the ways of mercantilism and minimum-wage exploitation. I never burgled a house. Held up a liquor store. Never boarded a crowded bus or subway car, sat in a seat reserved for the elderly, pulled out my gigantic penis and masturbated to satisfaction with a perverted, yet somehow crestfallen look on my face. But here I am, in the cavernous chamber of the Supreme Court of the United States of America, my car parked illegally and somewhat ironically parked on Constitution Avenue, my hands cuffed behind my back, my right to remain silent long since waived and said goodbye to as I sit in a thickly padded chair that, much like this country, isn’t quite as comfortable as it looks’.

PART 1 | PART 2 | PART 3

* https://www.theguardian.com/society/2020/jul/18/like-putting-out-a-fire-with-a-colander-of-water-my-life-as-an-antisocial-behaviour-officer

|