|

| |

'If historical experience taught anything, it was that a serious national crisis - a crisis of poverty, drugs, violence, crime, alienation from politics, uncertainty about the future – would not be solved without some great social movement of the citizenry. Such a movement would need to join together the inspiration and commitment of the anti-slavery movement, the civil rights movement, the labour movement, the anti-war movement, the gay and lesbian movement, the environmental movement, to turn the nation in a new direction.' |

| |

Howard Zinn, A People’s History of the United States, 1995 |

| |

"I am convinced that if we are to get on the right side of the world revolution, we as a nation must undergo a radical revolution of values. We must rapidly begin the shift from a thing-oriented society to a person-oriented society. When machines and computers, profit motives and property rights, are considered more important than people, the giant triplets of racism, extreme materialism, and militarism are incapable of being conquered." |

| |

Dr. King, 1967 |

PART 2

Throughout the pandemic loud appeals to cheap patriotism, at their loudest in the USA, drowned out more muted calls for coordinated worldwide cooperation. The World Health Organisation, which might have steered a planned global response to the crisis, was contemptuously marginalised – even as the rusty machinery of nation states proved inadequate to the challenges of the day. Just recently, the U.S. finally withdrew from the WHO. Although the worldwide lockdowns allowed our planet temporary breathing space, the urgent problem of climate change also awaits the concerted global response required. Where cooperation was called for, we got ‘virus competition’. Where internationalism was needed, we got only nativist rhetoric and protectionist nationalisms. Enforced and extant isolationism has combined with nationalism to especially deadly effect in Brazil, the UK and the US.

The UK has a per capita virus death toll second only to tiny Belgium. The US has the highest death toll in the world. The home of the free has paid a high price for its for-profit healthcare system, its bought-and-paid-for politicians, and a President in denial. Donald Trump blamed the pandemic on China. He blames most things on China. He blamed the Black Lives Matter protests on ‘outside agitators’ and the radical left, specifically anti-fascist activists. Such lunacy is only to be expected from a serial pandemic-denier who consistently tells it like it isn’t and infamously recommended the drinking of bleach as a way of containing and countering Covid-19. We eagerly await the imminent release of Anthony Baxter’s You’ve Been Trumped Too, which promises a reminder of how venal and dim the 45th President of the USA is.

Cornell West has pointed out that ‘black faces in high places’ haven’t discernably improved black lives. The Obama presidency was a disappointing failure in that and most other respects. Democrats seldom deliver. As Christopher Hitchens said of the Clinton administration, ‘the left gets words, the right gets deeds’. It nevertheless feels like an injustice that Obama isn’t in the White House now. His words alone might have made a difference. Hitchens felt Obama might have rescued at least one word from posterity. In a 2009 essay in The Atlantic, he says, ‘Exploited perhaps to greatest effect by James Baldwin, the word I have in mind is, “cat”'. Some of you will be old enough to remember it in real time, before the lugubrious and nerve-wracking days when people never knew from one moment to the next what expression would put them in the wrong: the days of “Negro” and “coloured” and “black” and “African American” and “people of colour”. Myself, I’m not sure Hitchins’ description of Obama as a cool ‘cat’ wasn’t an example of racial stereotyping but I’d be happy to tiptoe around questions of linguistic racism forever if only Obama could replace Trump tonight. Obama is bright and uses words well: Trump isn’t and doesn’t. Trump calls to mind an Elmore Leonard quip from Freaky Deaky: ’If the man was any dumber you’d have to water him twice a week’.

Jair Bolsonaro is none too bright himself. He’s played follower-the-leader, as ever, so it seems only a matter of time before Brazil catches the USA up and sets its own world-records. It’s to be hoped it’s surely only a matter of time, too, before Bolsonaro, Johnson and Trump are held to account for their callous, calamitous mismanagement of affairs. The erratic behaviour and belligerent rhetoric of these deranged dick-swingers has been in stark contrast to the composure and measured language of women like Jacinda Arden, Nicola Sturgeon, Mette Frederickson and ‘Mutti’ Merkel. The contrast between machismo and bombast on the one hand, competence and co–operation on the other presents an open-and-shut case for feminism. It is to be hoped, finally, that it’s only a matter of time before the world draws useful inference and wakes up, too, to the efficacy of the electoral systems that enabled such leaders to rise and shine.

From the moment the pandemic struck, 2020 has felt like a hinge year in history and a year to study history. In Remember This House, the unfinished work on which Raoul Peck’s I Am Not Your Negro was based, James Baldwin said: ‘History is not the past. It is the present. We carry our history with us. We are our history. If we pretend otherwise, we are literally criminals. I attest to this: the world is not white; it never was white, cannot be white. White is a metaphor for power, and that is simply a way of describing Chase Manhattan Bank’. It felt that history was shifting even before growing anger at the murders of Ahmaud Abery, Breonna Taylor and George Floyd sparked the protests against systemic racism and police brutality.

The USA has been here before. Many times. As H. Rap Brown famously said in 1967, ‘Violence is a part of America’s culture. It is as American as apple pie’. In 1852, the civic leaders of Rochester, New York, invited one of their most celebrated citizens, the former slave turned orator and abolitionist Frederick Douglas, to assist them with their Independence Day celebrations. They got more than they bargained for in Douglas’s thunderously eloquent peroration.

What to the American slave is your Fourth of July? ... a day that reveals to him more than all other days, the gross injustice and cruelty to which he is a constant victim ... your celebration is a sham; your bloated liberty, an unholy license; your national greatness, swelling vanity; ... your denunciation of tyrants, brass-fronted impudence; your shouts of liberty and equality, hollow mockery; your prayers and hymns, your sermons and thanksgivings, your religious parade ... bombast, fraud, deception, impiety and hypocrisy.

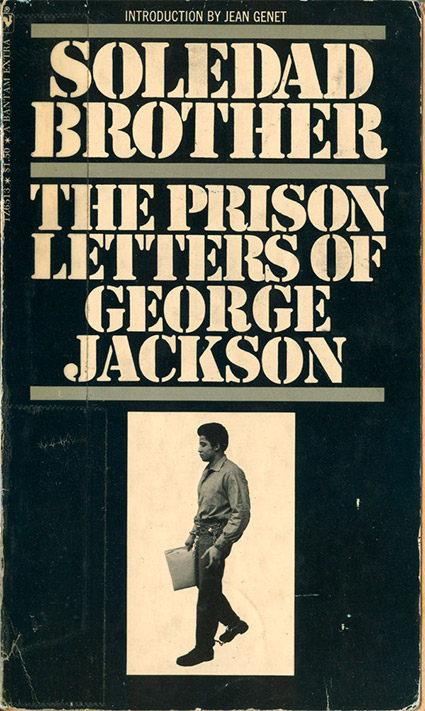

In his bestselling prison memoir Soledad Brother, George Jackson considered the condition of African-Americans in a nominally more enlightened era. ‘Born to a premature death, a menial, subsistence-wage worker, odd-job man, the cleaner, the caught, the man under hatches without bail – that’s me, the colonial victim. Anyone who can pass the civil service examination today can kill me tomorrow, with impunity’. In 1971, soon after completing Soledad Brother, George Jackson was killed during an escape attempt. He had earlier amended his will to bequeath his estate to the Black Panther Party. At the time of Jackson’s death both the party he founded, The Black Guerilla Family, and the Panthers had been in existence for five years. Second wave feminism was in full swing and the Gay Liberation movement was two years old, if we date it from the Stonewall riots. The USA had been involved in Vietnam for 16 years and in the murder of black people for two centuries.

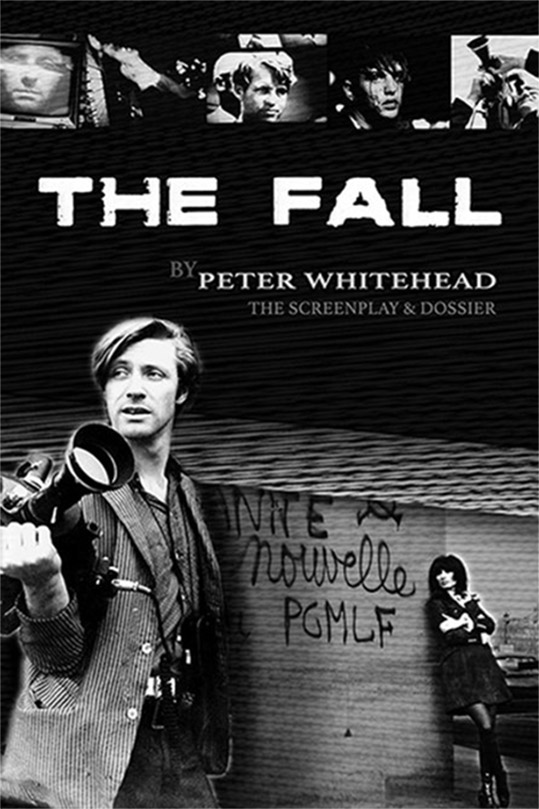

Peter Whitehead’s The Fall captures the optimistic energy and incandescent anger of those times, the hope and despair of America’s darkest hour to date. As an Englishman abroad, a Londoner in New York, he was acutely aware that he’d face flak for presuming to present the US to itself. In a TV interview he defended himself against accusations of effrontery by saying ‘Sometimes outsiders see us with a much clearer light that we see ourselves’. Sometimes outsiders see more clearly, full stop.

Whitehead – the conflicted maverick, accidental anarchist, enigmatic eccentric, polyglot, polymath, publisher, archivist of the sixties counterculture and witness to history – died last June. As last year ended so, too, did the British Film Institute’s Maurice Pialet retrospective. Although, the BFI had belatedly thrown its institutional weight behind the collective effort to fix Pialet firmly among cinema’s great directors, their screening of his magnificent TV series La maison des bois was the first in the UK since its debut in 1971. Back then, that seemed shameful. It seemed important. It felt as if Pialet and Whitehead had gone down to silence with their achievements unfairly overlooked. It felt unjust. It it still does. Now, it feels more urgent to say that black filmmakers don’t get a fair shake and that audiovisual culture is still experiencing a drawn-out white-out.

In 2016, I interviewed Barry Jenkins just before his debut feature Moonlight received its European Premiere at the London Film Festival. The interview took place at an LFF meet-the-directors ‘Afternoon Tea’ event. It was packed – with white film journalists and filmmakers. I’d gone along to interview Claire Simon about her film The Graduation, which documents the recruitment process at La Fémis – the elite film school in Paris that produced the likes of Claire Denis and Alain Resnais. I’d intended to press her about the lack of diversity in the French film industry, but then I saw Barry Jenkins – alone at his table, as journalists clustered and queued at all the others. Infuriated, I asked the event co-ordinator if I could book a standard ten-minute slot with Jenkins. She checked her clipboard list and immediately ushered to me to Jenkins and his lonely table. We chatted amiably – cinephile-to-cinephile – about John Cassavetes, Jacques Demy, Claire Dennis, Lynne Ramsey, and the under-representation of women in Hollywood. The co-ordinator kept circling her finger and nodding furiously to indicate we might continue. Jenkins and I talked for over half an hour. Nobody else approached the table. Was that because he was then an unknown director launching his debut feature or because he is black?

Moonlight was the first film with an all-black cast, and the first LGBT-related film to win the Best Picture Oscar. Mahershala Ali became the first Muslim-American to win an Oscar for his performance in the film. He also became the first black actor to win two Oscars in the same category when his performance in the travelling-while-black film Green Book earned him a second Best Supporting Actor award. That’s what systematic racism looks like. That’s how it divides in order to rule. Black and female filmmakers, though, aren’t alone in being poorly served by the film industry.

When he began publishing film scripts in 1966, Peter Whitehead said that the French ‘have accepted that the cinema is not just a factory for churning out films like motor cars; they have always recognised films as a part of their general social, ethical and political life, as a serious art form, and they’ve always written about them accordingly’. But even in Maurice Pialet’s native France, with its rigorous coverage of the moving image, non-conformists have been traditionally been marginalised and maligned. Here, too, outspoken outsiders like, say, Peters Watkins and Whitehead have historically been ostracised or forced into exile, with barely a murmur raised in their defence, by what Watkins calls the dominant ‘monoculture’.

The more challenging their work, the more infrequent the commissions, the smaller the budgets; the more pronounced their resistance, the louder the denunciations; the more provocative their dissent, the more deafening the silence. The ‘monoculture’ is global. It valorises the comfortable, comforting and conventional at the expense of the dangerous, discomforting and difficult. The exclusion of Jenkins, Pialet, Watkins, Whitehead, and their ilk from the cannon used to make me angry. Now, the spotlight falls on racist films and the lack of diversity in the film industry. Now, the cannon itself makes me angry. If the pandemic had anything to teach, it’s that we’re all connected and everything’s connected. The culture that excludes black and female filmmakers, mavericks and outsiders, strides forward still – with its batons raised and guns at the ready, tear gas and pepper spray to hand.

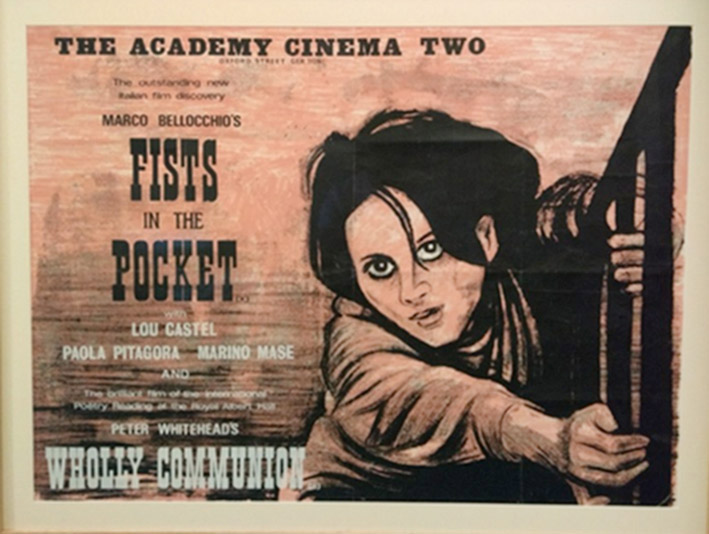

Happily, interest in Whitehead’s work has been growing steadily for a number of years and, inevitably, it has increased further since his death last year, aged 82. The BFI made another valuable contribution to a wider drive to rescue a supremely talented filmmaker from obscurity, back in 2007, when it hosted a long overdue Whitehead retrospective. It also followed through, that year, by releasing the DVD Peter Whitehead and the Sixties containing three of Whitehead’s films: Wholly Communion (1965), Jeanetta Cochrane (1967), and Benefit of the Doubt (1967). Fast forward a decade, and the Albert Hall screened three of Whitehead’s films within its ‘Summer of Love Revisited’ season: Tonite Let’s All Make Love in London (1967), Pink Floyd: London 66-67 (1968), and Led Zeppelin Live (1970). Most recently, the ICA hosted screenings of The Fall and Tonite last November with the assistance of Whitehead aficionado Steve Chibnall of De Montfort University Leicester, home to the Peter Whitehead Archive.

In his early films, Whitehead documented the sixties counterculture – with a sceptical detachment born of his working-class roots in Liverpool, his preference for classical music, and his grounding in science. He studied Physics at Cambridge and his first film, Perceptions of Life (1964), detailed the development of microbiology and DNA. Wholly Communion documented the International Poetry Incarnation at the Albert Hall in 1965, the legendary event that brought together disparate bohemian-radicals and fused them into one body, which transmitted the anti-authoritarian power of poetry to the wider world, and which Whitehead called ‘the first great hippie happening in London’. It was certainly a formative moment for the counterculture and for Whitehead, who used the light, handheld Éclair camera that would become his stock in trade for the first time. The event, dreamed up as a wild throw of the dice by stoned regulars at Better Books, was packed. Thousands gathered to hear the likes of William Burroughs, Allen Ginsberg, Laurence Ferlinghetti, and Adrian Mitchell – who stole the show with his precocious anti-Vietnam War poem ‘To Whom It May Concern’.

The success of the film helped Whitehead establish Lorrimer Publishing with the novelist and filmmaker Andrew Sinclair (of Under Milkwood fame). Feeling that Wholly Communion hadn’t done justice to the poems he’d filmed, he secured permissions and set them down in a book of the same name. Published in 1965, Wholly Communion was the first of over 70 Lorrimer publications. The Lorrimer backlist included Whitehead’s own novels and memoirs, and film scripts – from Godard’s early films, (which he painstakingly transcribed and translated on a Moviela) to canonical classics (published with L’Avant-Scene of Paris, who’d been publishing film scripts since 1961). Whitehead’s painstaking work on those early Godard scripts (Alphaville, Made in the USA, Le Petit Soldat, Pierrot le Fou, Weekend) intensified a lifelong fascination-cum-obsession with the Franco-Swiss maestro which, as we shall see, informed all Whitehead’s work.

Whitehead’s pioneering promo-videos for Top of the Pops include a superb promo of The Rolling Stones’ We Love They (1965) and his legendary film for The Dubliners’ Seven Drunken Nights (1967). His pop films prefigured the MTV videos of the 1980’s, much as his documentary of the Stones’ 1965 Ireland tour, Charlie is My Darling, prefigured rock documentaries’ like D.A. Pennebaker’s Dont Look Back, and as Wholly Communion prefigured music documentaries such as Michael Wadleigh’s Woodstock. Those Whitehead filmed comprise a veritable roll of honour of the pop aristocracy: The Animals, The Beach Boys, Chris Farlowe & and the Thunderbirds, Jimi Hendrix, John and Yoko, Nico, The Shadows, The Small Faces, Jimmy James and the Vagabonds, and Led Zeppelin.

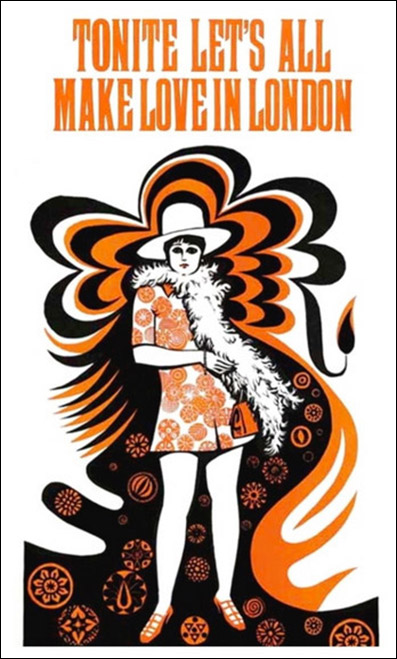

Tonite caught the moment, in the ‘Summer of Love’ of 1967, when the post-mod generation began to take a political turn. The film both contributed to the construction of the myth of the ‘swinging sixties’ and implicitly criticised it by focusing on class and collapse of empire. In the film, Julie Christie speaks for the in-crowd when she says, ‘a good time is much easier had by all than ever before’. A working-class Glaswegian, interviewed about the ‘swinging sixties’ on TV, spoke for others when she said, yes, she’d heard a lot about it but it must have swung right past her without stopping. Shortly after being appointed as Scotland’s new Makar, Liz Lochhead said of the era of free love: ‘The sixties swung for me as much my friends but I was a serial monogamist and then was married for 25 years’.

Although Whitehead had forced his Scouse accent down as he moved on up, he remained class conscious and fully aware that the myth outbid the reality. In the film, Whitehead intercuts interviews with pop luminaries such as Christie, Michael Caine, and Mike Jagger with filmed live performances by The Animals, The Small Faces and Pink Floyd. But he gives pride of place to a pragmatic working-class lad from Bradford. David Hockney says London’s too expensive to swing and adds: ‘If next week the country collapsed but on the same day you met your absolute true love, you wouldn’t give two hoots about the place collapsing, you’d think all’s right with the world, let’s have a sandwich and a glass of beer. It wouldn’t matter’.

Whitehead peeled away from pop and dipped his toe in radical theatre for Benefit of the Doubt, filming a performance of Peter Brooks’ absurdist anti-Vietnam War play US/Us. The play furthered the project of experimental, self-reflexive, Brechtian drama that Brooks and the Royal Shakepeare Company had earlier developed in Peter Weiss’s The Persecution and Assassination of Jean Marat as Performed by the Inmates of the Asylum of Charenton under the Direction of the Marquis de Sade. Brooks was at pains to play down kneejerk anti-Americanism but the plays nonetheless asked how, ‘the Americans are able to blow the legs off children and then, with true, deep conviction, sew them back again’. It was far from straight-up agit-prop, though. Brooks and his cast interrogated what it meant to observe the war from afar and highlighted British complacency and complicity. Just as Godard, Marker, Varda et al. did, that same year, in the portmanteau film Far From Vietnam, Benefit of the Doubt film brought that war home to audiences. As one contemporary critic said, while reviewing it, both the play and the film aimed ‘to denounce the easy conscience, to destabilize the audience, and also require them to question themselves, even to the point of taking action’. Whitehead filmed in colour but used black & white for sequences in which the actors discussed the work and their own performances. He took that interrogatory, self-reflexive style forward into The Fall along with the kinetic cinematic techniques that make Tonite a joy to watch.

Whitehead’s cinematic journey would next draw him into politics and to the USA. In the autumn of 1967, he flew to New York to make The Fall – a film that, perhaps more than any other, captured the mood of the moment as the US teetered on the brink of another civil war. In 1967, the Kerner Commission was set up in the wake of the riots of ‘Long hot summer of 1967’ that feature in Kathryn Bigelow’s Detroit. It concluded that the country was moving “toward two societies one black, one white – separate and unequal.” A nation built on violence, slavery, the slaughter of indigenous Americans, and the systematic looting of the resources of the whole wide world, was finally forced to look at itself in the mirror. And Peter Whitehead was there to witness the fallout and the fall.

In the five-year-long burst of intense energy and invention during which he forged his lasting legacy, he documented and deconstructed the myth of ‘swinging London’ (which he came to regard as a CIA plot to sanitize and depoliticise rebellion); filmed the US during its testing time (what he called its ‘successful power failure’), witnessed the moment the Civil Rights Movement and New Left moved beyond the limits of legal protest, first to resistance and then to armed revolution (about which he fantasised); and worked through the collapse of his own divided self.

He certainly drove himself hard, too hard, and by the time he made The Fall he was a worn out insomniac beset by anxiety and self-doubt. His Godard fixation can’t have helped his self-confidence. He was also plagued by a debilitating, undiagnosed arthritic condition. He was falling apart at the seams as the USA was and that conjunction adds enormously to the film’s force. Writing in the New Yorker about the damaged, recalcitrant, orphan at the centre of Maurice Pialat’s masterpiece L’enfance nue, Richard Brody says: ‘His violence and deceit are a sort of existential affirmation, a mark on the world, the wrenching of a space – even a dreadful and self-punishing one – within which he makes his identity and recognizes himself.’ Peter Whitehead’s tragedy was that while making his mark on the world with The Fall, he was driven half-mad by violence, deceit, and self-deceit. Riven by hope and hate, he buckled under the contradictions of an era torn between the promise of change and the pandemonium of its curtailment.

The Fall (Peter Whitehead, 1969)

Part hired gun, part renegade, Whitehead collapsed under the weight of his own contradictions too. Primed for experiment by his time at the Slade School of Art, prepared for documentary by a spell as a news cameraman (for Greek and Italian TV companies, for instance), he thrashed around in that familiar no man’s land between art and commerce, budget hustling and aesthetic integrity, hack work and political engagement. Like avant-garde fellow travellers Alan Burns and B.S. Johnson, Whitehead was an inside-outsider or insider-outsider, as one film critic put it, ‘an outsider with inside access’. All three derived income from conventional commercial sources but bit the hand that fed. Burns worked with Johnson on Unfair (a 1971 protest film against Industrial Relations Bill) and with Whitehead on Jeanetta Cochrane (a 1967 short again featuring footage of Pink Floyd). The London scene of the sixties was a close-knit cliquey affair that initially fused the underground and pop aristocracy. Whitehead had a foot in both camps. He was a regular at Better Books (a radical hub of the counterculture) and helped launch the London Filmmakers Co-op (a focal point of the avant-garde) from there. But he also bankrolled Pink Floyd’s first recording (Syd Barrett was a pal from Whitehead’s Cambridge days) and generally, profited from his reputation as the go-to filmmaker of the in-crowd – back when things were loose-limbed and a phone call could go far.

He was also an insider-outsider in on the political scene. Albeit politicised, to a degree, by the British class system and his immersion in the counterculture, he remained muddled-headed and was well off the political pace when ’68 erupted. After finishing The Fall, he said, ‘The Promethean Fire of Revolution is in our blood whether we are conscious of it or not’ but his view of the perfect revolutionary was one who floated somewhere between the Right and the Left. He recognised Rudi Dutschke and Daniel Cohn-Bendit as kindred spirits, though, and would doubtless have warmed to the cherubic Danton’s reprise of the old battle cry, ‘Laudace, l’audace, encore l’audace’. Whitehead’s speed-fuelled, mescaline-infused, Godard-influenced, pop-art-poem-cum-essay-film-cum-documentary The Fall is nothing if not audacious. Audacious partly because he was unravelling.

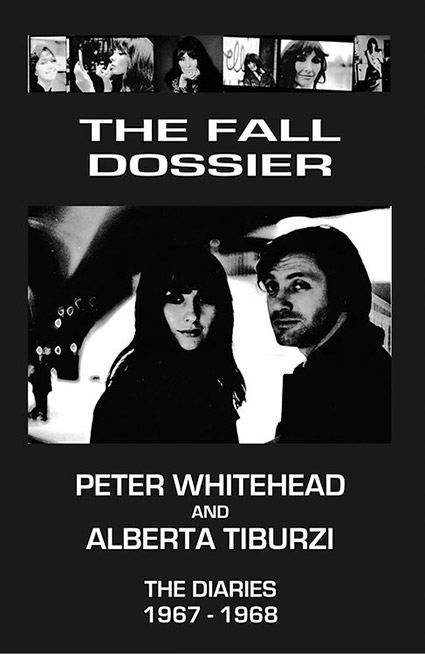

Whitehead may also have been riven by his personal relationships. He was a man of prodigious sexual appetites, with a marked propensity toward misogyny. As Steve Chibnall says, he was drawn to ‘the dangerous power of pop’s Esperanto to break down barriers between performers and audiences, transcend the fixities of class and social station, and liberate female libidos’. Might he have belatedly developed a guilty conscience? It would be instructive to ask the four wives and seven children he left behind. The evidence he offers in his self-published memoir The Fall Dossier, suggests he had. I raised the matter with his occasional collaborator Jenny Spires at an ICA screening of Tonite. She thought it unlikely: ‘Yes, he was a womaniser but he was no misogynist. He loved women’. We can’t know. We do know that he was 31 when he made the film and that, in an era that fetishized youth even more than ours, a kind of cultural mid-life crisis would’ve pause for thought. Setting aside pop psychology and speculation, the work is all and if we look closely within it we’ll find the clues to what made Whitehead tick and cease to tick.

Whitehead disparagingly referred to his work in documentary as ‘prostitution’ and ‘filming facts’ but he was delighted when Tonite Let’s All Make Love in London received the endorsements of Richard Roud and Susan Sontag and he was invited to screen it at the New York Film Festival. Better still, he was invited to repeat his scattergun rapid-fire documentation of the London scene for the New York scene. Off he set, with his cameraman and assistant Sebastian Keep, to film The Fall between October 1967 and May 1968. Whitehead says, ‘I set out to make a film about protest and violence. That was all I had to guide me – the compulsion to film a city, a people, a culture, a society that was falling apart’. Little did he know he himself would fall apart in the process. At the height of the fighting in 1968, as the American dream ruptured, Whitehead’s camera was rolling and his inner struggle for sanity was coming to a head. Not helped by the speed and mescaline he consumed or by his insomnia, it was heading in the wrong direction. Like Huxley before him, he sought the ‘glassy essence’ of humanity in drugs. He considered the discovery of mescaline ‘the most import event’ of his life at that time and he may be right; certainly, consumption of significant quantities of it affected his relationship to reality. As he says in Nothing to Do with Me, a short film portrait made by his erstwhile assistant Anthony Stern soon after The Fall was finished: ‘(Mescaline) simply cuts out the reasoning mechanism . . . this reflective thought process which I see as a kind of aggression and act of violence against our own experience’.

Soon after he arrived in New York to start filming, Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated. Whitehead’s mind was already so scrambled he felt he was somehow to blame. ‘I felt responsible for the act’, he later said, ‘I imagined I had done it myself!’ He may have heard Dr. King’s final speech of the 3rd of April 1968, in which King said, ‘I don't know what will happen now. We've got some difficult days ahead. But it really doesn't matter with me now, because I've been to the mountaintop’. Whitehead had been on literal mountaintops himself, with his friend Ted Hughes, as a twitcher in search of hawks. Now he’d spread his wings as a director and as a twitchy would-be-revolutionary, only to be burnt by the sun.

It is clear from The Fall Dossier and The Fall itself that Whitehead was suffering. In the first third of the film, he shoots himself and his partner, the Italian model Alberta Tiburzi, half-dressed or undressed in a single flat – as if he’s too ill to go out and face the world so must make a film indoors. The film and Whitehead’s collapse testify to what happens when the revolutionary impulse careers into the solid brick walls of power structures that had been built to last. Like W.H. Auden’s W.B. Yeats, he sang ‘of human distress/in a rapture of distress’. Fused with a strong sense of personal and social instability, the fall of the film’s title refers both to the fall from grace of the USA and Whitehead’s own collapse. The film’s critique and auto-critique meshed perfectly; Whitehead’s move to the left matched that of the milieu he filmed.

Early in The Fall Whitehead flashes up a Godardian intertitle: ‘Film as a Series of Historical Moments Seeking a Synthesis’. That synthesis eluded him but he created a messy, magnificent kaleidoscopic cinematic assault on the senses. The film’s form does full justice to the mayhem sweeping the US in the spring of ’68. Whitehead shoots from the hip, deploying all the tricks and techniques he’d honed shooting pop: the overlayering of images and oversaturation of colour, the whip pans, freeze frames, dutch angles, close-ups, fade-outs, jump cuts, stills, stroboscopy and all.

Tonite Let's All Make Love in London (Peter Whitehead, 1967)

Reviewing Tonite, Raymond Durgnat, Whitehead’s old mucker from Better Books and the London Filmmakers’ Co-op, notes that Whitehead’s kaleidoscopic style was ‘no mere gimmick, but absolutely right for suggesting the alienation, the unreality, the edgy beauty, the instability, of our bright, ephemeral, syncopated world’. Whitehead’s anarchic cinematic style was also perfect for probing the febrile chaos of the US and New York in 1968. Enthralled by Schoenberg’s notions of the emancipation of dissonance and in thrall to Godard’s coalescing theories on the rupture of sound and image, Whitehead emancipated himself, finally, from the constraints of commercial cinema and restrictions of documentary.

Whitehead was much taken with Pablo Neruda’s concept of ’concrete surrealism’ and he wasn’t afraid to throw the paint around and mix things up. Richard Roud described The Fall as ‘an attempt to come to grips with today, both in terms of its content as well as of its form’. The operative word there may be ‘attempt’ but Whitehead came as close as anyone to putting the mess of ’68 on film because he went as close as anyone else to events that year. He didn’t, however, entirely escape the twin problems of exposure to reality elucidated by Robin Wood in the Lorrimer script for Godard’s Weekend. Firstly, ‘the great formal crisis of modern art: the tendency of works that honestly reflect a fragmentary and disintegrated culture to become themselves fragmentary and disintegrated’. Secondly, ‘the danger of total exposure: the artist, sensitively aware beyond others through the very functioning of his creativity, may harden, perhaps destroy his finer sensibilities . . . to evolve a protective covering of partial insentience’. Wood’s formulations seem quaintly old-fashioned now but they fit with the romantic sensibility Godard and Whitehead shared. As Wood says, Godard was aware of these dangers: in Made in the USA, Paula Nelson wonders why she hasn’t wanted to vomit since her involvement in the world of action (‘Toujours le sang, la peur, la politique, l’argent’). Whitehead less so.

Whitehead dubbed Tonite a ‘pop concerto for film’ and The Fall might be described as a tripartite ‘pop concerto for politics’. The film, like Whitehead himself, was marked by the successive assassinations of Dr. King, and Bobby Kennedy, and, sandwiched between them, the assassination attempt on German revolutionary Rudi Dutschke. In the first of a series of hastily revised scripts, he’d intended to tell the story of a freaked-out, politicised filmmaker driven to revolutionary action and political assassination. The real life assassinations jolted him out of the idea he could write history as story. If he’d gone ahead, he might have predicted Travis Bickle. In The Fall Dossier, Whitehead says: ‘The fact of (Dutschke’s) assassination, so soon after Luther King’s is, of course, shattering ... the relationship between my film’s main theme of assassination and the two of King and Dutschke was so monumental that my pose ... became obvious ... It looks so much a fraud, too much an irony, a coincidence ... the plane, in fact, hit a bit of turbulence’. His inner turbulence fed into a film that pulses with a kinetic energy that rips through the screen.

Whitehead had a knack for working himself in close to the centre of events. It’s as if he were so comfortable with his camera, so at one with it, that nobody noticed him and it. He’s in there on the shoulder of things whether he’s filming the likes of Kathleen Cleaver, Bobby Kennedy, Robert Lowell and Arthur Miller at rallies, in the face of corporate right-wing pencil-necks screaming ‘Bomb Hanoi, bomb Hanoi’, documenting the fall-out from the riots in Newark, or with citizens arguing about Vietnam and War. Sometimes one wishes Whitehead weren’t so close to the action, as when he shows Destructivist performance artist Rafael Montañez Ortiz beating a chicken to death against the strings of a smashed piano. When I last watched The Fall, a group left the cinema at that point in the film, thereby making Ortiz’s point about the need for theatrical acts of brutality that operate as a means of destabilizing audiences and delegitimizing violence. As if to calm the horses, Whitehead layers in less sanguinary, if no less absurd forms of street protest theatre too. Inevitably, he also includes some of his trademark pseudo-psychedelic club and party scenes.

The first third of the film is, as I say, dominated by interior shots of Whitehead frolicking with Alberta Tiburzi – who he effectively cast to play Anna Karina to his Godard. In 2009, Whitehead would return to the idea of assassination and his fixation with Karina and Godard. In Terrorism Considered as One of the Fine Arts, which he called a homage ‘to my great hero Jean-Luc Godard’, he casts his female characters as Karina (‘my image of the perfect French girl’) reprising her roles in Alphaville, Pierrot le Fou and Vivre sa Vie. It’s as if he were suggesting, as first D.W. Griffith and later Godard did, that all a film requires is ‘a girl and a gun’. He’d found his girl, his pet Anna, and later, as the revolutionary fire rose in him and around him, he would buy a gun. More importantly, as first Hitchcock and then Godard did, Whitehead was inserting himself and ‘the subjective’ into his work. Sadly, as with Hitchcock and Godard, narcissism and misogyny trump Bressonian detachment and, well, good old-fashioned human decency.

Much has been written about Whitehead’s Godard fixation, more will doubtless follow, but Giandomenico Curi’s exemplary essay ‘Re-creating the Gaze’ cannot be improved upon. Here, suffice it to quote Whitehead, selectively, and reveal that fixation in his own words. In 2006, the Pompidou Centre, Paris hosted a major exhibition on Godard’s work: Voyage(s) in Utopia: Jean-Luc Godard 1946-2006. Whitehead’s contribution to the exhibition catalogue, Documents, was a love poem or ‘anti-poem’ entitled ‘Jean-Luc: I Hate You!’ It is an embarrassingly dire, tender, scatological encomium – but nothing if not honest.

Free, free! Free at last. I escape you, I sleep a whole night without dreaming of you. Your haunting is over ... Your voice, your fault Jean-Luc! You were my mirror and stole my soul. But I walk on ... THE FALL. In the Beginning was the Image ... I film Stokely Carmichael: Was he bought out by the CIA? H Rap Brown: Did they kill him? Your love of American MOVIES can’t have been easy to live with. Nor were you. Nor was she ... My every girl called ANNA. Students drenched in blood are driven off in BLACK MARIAS (I like that name, damn it!). SDS. Students for a Democratic Society... Paris 1968. It didn’t happen. It was a film made by you Jean-Luc. We were your extras. They thought it real, you fooled them all! As you created Alphaville! Everything became VIRTUAL. Free and unfree simultaneously. A girl is a girl is a girl ... Forget the real, it is unbearable. In the beginning was not the Word, in the beginning was not the Image. IN THE BEGINNING WAS THE IMAGINATION. What you imagined, envisioned, I have tried to live. To know and accept the flawed dreaming people you gave birth to, the city and society you challenged. A life I have vicariously lived despite myself. What can I do but hate you? At times...

PART 1 | PART 2 | PART 3

|