|

PART 3

Less has been said of Antonioni’s influence on Whitehead and vice versa. Watching The Fall at the ICA late last year - 50 years to the day, almost to the minute, since it had first screened there – stretched and twisted time. My mind turned to photographer John Cowan’s early one-man shows ‘Through the Light Barrier’ and ‘The Interpretation of Impact Through Energy’ - which might’ve lent their titles to The Fall. Cowan’s studio appears in Blow Up! It was Cowan, therefore, not David Bailey or the Terries Donovan or O’Neill, who was the model for Antonioni’s boy-about-town photographer. It was therefore Cowan as much as Antonioni and David Hemmings who Whitehead tips his cap to in The Fall when he reprises the Verushka photo-shoot from Blow Up! This scene, with Tiburzi cast as Verushka, occurs before Whitehead impersonates Hemmings talking into a phone. Whitehead visited Antonioni on set as he shot the antique shop sequence for Blow Up! Antonioni repaid the courtesy with a visit to Whitehead’s Soho flat. While there, the Italian maestro watched an interview with David Hemmings that Whitehead had filmed but elected not to use in Tonite.

In 1970, a couple of years after Whitehead had abandoned the revolution and gone off to breed falcons for autocratic Sauds, film history turned full circle in the opening scenes of Zabriskie Point. Antonioni’s scenes of radical student debate replicate the campus scenes from the final third of The Fall. There’s Kathleen Cleaver, again, discussing tactics and strategy as she did at Columbia and in Whitehead’s film. White radical: ‘I think we understand. A lot of us have understood what makes Black people revolutionary. But, what's going to make white people revolutionaries? Cleaver: ‘The same God damn thing that makes Black people revolutionaries’. White radical: ‘But, it's not happening the same way’. Cleaver: ‘You just wait. It’ll happen. You don't have to do anything to instigate it’. And there, too, are Pink Floyd. They appear on the soundtrack of the final explosive scenes of Zabriskie Point - Antonioni’s ode to the counterculture and the revolutionary violence that erupted when democratic protests proved futile in the face of increasingly brutal repression.

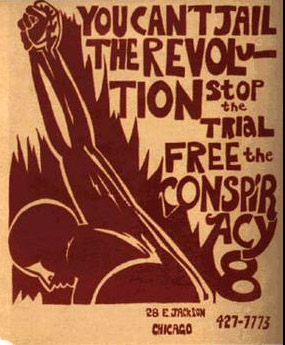

Whitehead was enraged by police brutality at Columbia in May 1968. Antonioni was enraged by his encounter with it in Chicago later that year. He and Haskell Wexler witnessed the police riots at the Chicago Democratic Convention and their anger fed into Zabriskie Point and Medium Cool respectively. Antonioni was tear-gassed in Chicago. Tom Hayden, whom Whitehead had filmed during the Columbia occupations, was in Chicago too and was one of the Chicago Eight charged with conspiracy and incitement to riot. Long before he set out on his own ‘long march through the institutions’, Hayden said the Left’s main problems were that it never thought of winning and was too content to ‘existentially enjoy and suffer’. Perhaps, but he also said that if radicals seem to seek the unattainable it is only to avoid the unimaginable. Hayden said of himself, ‘I’m Jefferson in terms of democracy, Thoreau in terms of the environment, and Crazy Horse in terms of social movements’. It’s hard to imagine how he’d have reacted to the sight of protesters tearing Jefferson’s statue down, much as their forebears had torn down the statue of King George 111 during the War of Independence. State violence begets violent opposition.

Film begets film too: Godard influenced Whitehead, Whitehead influenced Antonioni, Antonioni and Godard influenced Whitehead and, well, everyone. The BFI’s Geoff Andrew proposed an A-Z of film-makers that owe a debt to Antonioni. Andrew says: ‘How about starting with Theo Angelopoulos and ending with Andrey Zvyagintsev? – but then I realised I’d have to make some impossible choices: Davies, Denis or De Palma? Jancsó, Jarmusch or Jia Zhangke? Klimov, Kieslowski or Kubrick? Malick, Mann or Martel?’ One day, I’ll compile a list of those influenced by Godard.

Whitehead’s time filming the The Fall was bookended by the assassinations of Dr. King and Bobby Kennedy. The film itself is bookend by two exhilarating scenes fully a match for Antonioni’s explosive Zabriskie Point finale. A lift plummets from and soars back to the roof of the uncompleted General Motors Building in Manhattan, in each instance accompanied by the intense, insistent Hammond-driven jazz-pop instrumental ‘Here It Is’ by The Nice. That track lifts the images to greater heights. Like Hendrix’s ‘Star Spangled Banner’ it is an explicit act of détournement. The Nice turned Leonard Bernstein’s original ‘America’, a schmaltzy standard of the American songbook, into a furious protest song. ‘When the mode of the music changes, the walls of the city shake’, said Allen Ginsberg, after Plato. Whitehead is announcing the film’s location, declaring himself an outsider – an Englishman in New York, and setting the film’s questing, rebellious, testy tone.

When I asked Sebastian Keep how he and Whitehead achieved that remarkable footage, he said, ‘I didn’t have a lot to do with it. Peter somehow bunked in there, strapped himself to the roof of the cage, and just filmed’. Looking back from an era in which filming is circumscribed by health and safety concerns, it seems unthinkable that a filmmaker could screw his courage to the sticking point and venture such a brazen act. It’s a scene straight out of Vertov’s Kino-eye playbook, Whitehead as a-man-with-movie-camera. ‘I am an eye. A mechanical eye I, the machine, show you the world as only I can see it. I free myself for today and forever from human mobility ... Thus I explain in a new way a world unknown to you.’ The scene is typical of the brio, bravado and courage with which Whitehead seized his shots.

After the murder of Dr. King and the attempt on Dutschke’s life, Whitehead didn’t go out for over a week, simply watching events unfold on TV. Paralysed, he felt he couldn’t very well film black rioters as a voyeur. ‘I was on their side’, he said, ‘and if I was on their side, I should have been out there looting with them.’ He shook himself down, though, and set about putting himself about. The film’s three parts chart his shift from detachment to engagement. Whitehead placed himself inside history: initially, as observer and witness only, while filming the burnt-out ruins of Newark and Dr. King’s memorial service in Central Park; subsequently, in a desperate search for solutions, while filming Bobby Kennedy on the campaign trail; and, finally, as a fully politicised participant, by joining the student occupation of Columbia University.

The students and faculty at Columbia acted against local expressions of racism and militarism; specifically, against the construction of a gym that effectively stole a public park from the black community and was to feature a separate ‘back door’ entrance to Harlem (‘Gym Crow Must Go!’), more generally, against the university’s ties to the military-industrial complex though the Institute for Defence Analyses. The Columbia students, ‘the children of Marx and Coca Cola’, acted against racism and repression at home but they were also opposed to the ‘Vodka-Cola’ dictatorships of the Eastern Bloc and Juntas of Latin America, and, most obviously, the Vietnam War. The campus occupations occurred against the backdrop of the Tet Offensive, the abdication of Lyndon Johnson, the murder of Dr. King and the riots that followed. Those events and the police brutality in communities and on campuses pushed radicals leftwards at precisely the time George Wallace, the Trump of the era, was pushing the mainstream parties to the Right. Having experienced police brutality up close and personal, many of those Whitehead filmed immediately joined the Black Panthers. Others, such as David Gilbert and Kathy Boudin, Ted Gold and Mark Rudd helped form the Weather Underground – to fight fire with fire or in the forlorn hope of providing the spark that would ignite the prairie fire of revolution.

A few months before the Columbia occupation, in his final speech before his assassination, Dr. King said, ‘Whenever Pharaoh wanted to prolong the period of slavery in Egypt, he had a favourite formula for doing it ... He kept the slaves fighting among themselves ... When the slaves got together, that’s the beginning of getting out of slavery’. Unfortunately, the Columbia occupations didn’t unite black and white students: the European-American Students for a Democratic Society and African-American Student Afro Society factions largely kept their distance from one another during the occupation and subsequent strike, and, as H. Rap Brown said, ‘Harlem wasn’t going to rise up because some white cops were beating up some white kids’. Nor did the violence that occurred during the mop-up operation at Hamilton Hall bring the SDS and SAS together. Several SDS students did, however, meet with local Black Panthers in the aftermath and agree a modicum of mutual aid.

In his account of the police brutality that ended the occupation at Columbia, Whitehead claims he was forced to run a gauntlet of NYPD thugs and beaten black and blue. When I asked Sebastian Keep, Whitehead’s assistant from those days, how the hell they got out alive, he told me they hung back by the front door when the riot police burst in, waved their press passes, and strolled off uninjured. Whitehead would also claim that the Columbia students had watched Godard’s La Chinoise before they seized the day. It certainly makes another nice story. In an interview for Films and Filming in January 1969, he says, ‘I could no longer distinguish between fiction and reality and both were intolerable. I collapsed. I fell to pieces. I’ve put myself back together by giving form to the film, by making it “make sense”. Some will say the film is mad; I am mad. I say the world is hardly in a position to judge’. Which sounds a lot like something R.D. Laing may have said.

Prone to hyperbole and little white lies, Whitehead cultivated and nurtured his own mythology. In 1998, mythomaniacs Chris Petit and Iain Sinclair added grist to the mill of the Whitehead myth. In their Channel 4 film The Falconer, they created an aptly esoteric ‘fictionalised biography’, ‘in which nothing is true and everything is permitted’, blending fact and fiction themselves while sifting through the facts and fictions of Whitehead’s extraordinary, and extraordinarily elusive life. The two cinephiles and Godard aficionados were more interested in Whitehead’s fascination with falcons than his relationship with Godard, and they weren’t at all interested in his flirtation with radical politics. Consequently, they merely muddy the waters of Whitehead’s already mysterious, murky personal and political past.

I once hosted an event with Sinclair, in which a member of the audience asked him if he took ley lines and the occult seriously or merely used them as metaphors. The poet laureate of subterranean London and bard of the marginal and maligned, replied, amusingly, if glibly that he took them seriously as metaphors. Whitehead’s interest in the occult is writ large in his late films and novels, which he disowned and which I’m happy to pass over without comment. I can’t bid Petit and Whitehead a fond farewell, however, without saluting their 70x70 film season – curated to coincide with the latter’s 70th birthday in 2014 and composed of films mentioned in his books. In Sinclair’s words the season featured 70 films with ‘energy, attack, context – but which stood outside the usual registers of excellence’. It was an ‘anti-pantheon – films that were well worth holding in memory and for discussion but which had no place in the established pantheons of cinema’.

The films screened at various, appropriately selected venues across London. Godard was heavily represented in the season, Peter Brooks was in there, and Whitehead too, in The Falconer. It felt like a cinematic ley line, if such a thing exists. For one triple-bill featuring the delights of Buñuel, Cassavetes, and Terence Young, four people turned up. So, the projectionist presented almost one film for every member of the audience. Introducing those forlorn screenings, compere Gareth Evans said cinema was ‘not as a passing interest, but a passing on of interests, a baton relay in the long race of collective sight’. That ley line or baton relay is not a matter for die-hard cinephiles only. It also implies a vital passing on, and sharing of information and ideas of hug social and political importance. Peter Whitehead may have disparaged the ‘filming of facts’ but if we lose sight of facts we’re left not with little white lies but the colossal lies of governments, the ‘big lie’ chillingly described by Herr Hitler in Mein Kampf.

The 70x70 season also contained a Goethe Institute double-bill of Jean-Marie Straub’s 1968 film The Bridegroom, the Actress, and the Pimp and the 1978 anthology film Germany in Autumn (with contributions from Rainer Werner Fassbinder, Alexander Kluge, Edgar Reitz, Volker Schlöndorff, et al). Between 1968 and 1978, as Richard Vinen points out in his book The Long ’68: Radical Protest and Its Enemies, the unexhausted but fragmented energies and ideas of May 1968 rolled on, only to shudder to a halt with the grim emergence of the Reagan-Thatcher conservative-counter-revolution that ushered in market Stalinism and the billionaire class. While Whitehead licked his wounds back in London and put himself back together by putting his film together, the storm of ’68 continued to rage. The anger on campuses and on the streets intensified in response to the increasing brutality of the Vietnam War and the violence of the state. In 1971, W.H. Auden said, ‘What a country calls its vital economic interests are not the things which enable its citizens to live, but the things which enable it to make war’. The Vietnam War would rumble on until the fall of Saigon in 1975.

While many on the radical left turned inward in a quest for the elusive holy grail of self-realisation, others continued to ‘bring the war home’ and fight on. Whereas before the injunction had been to ‘Kill the cop in your head’, now the emphasis was on ‘the revolution in the head’. The drift from words to deeds was manifest in the shift from the NAACP and the SNCC to the Panthers, from the Berkley Free Speech movement and the SDS to the Weather Underground. The dead end of peaceful protest lead to the dead end of revolutionary violence as new armed groups sprang up to provide the state with ammunition for repression (the Angry Brigades in the UK, the Black Panthers and Weather Underground in the US, Action directe in France, MIR in Chile, the Red Army Faction in Germany, Prima Linea and the Red Brigades in Italy, the Japanese Red Army, Sandero Luminoso in Peru, etc).

©rozpayne/newsreel collective

In his magisterial A People’s History of the United States, Howard Zinn said of the sixties, ‘Never in American history had more movements for change been concentrated in so short a span of years. But the system in the course of two centuries had learned a good deal about the control of people. In the mid-seventies, it went to work’. It went to work much earlier than that. In the late sixties, the dark state responded to the rise in militancy within the Black Power movement and the New Left by increasing the activities of the FBI’s anti-democratic, extrajudicial COINTELPRO programme. J. Edgar Hoover’s pet project, the programme had been founded in the late fifties to destabilise the Left -much as the CIA’s Operation Gladio had destabilised the European Left in the post-war perioed and as its Operations Black Eagle and Mongoose would destabilise the Latin American Left.

Although Bill Ayers, Bernadine Dohrn and others in the Weather Underground evaded the FBI until 1980, the Feds assassinated Marc Clarke, Fred Hampton and other Panthers. Other black revolutionaries died in black-on-black shootings by former comrades, often as a result of the COINTELPRO highly effective, generously endowed destabilisation campaign. Sympathetic celebrities like Jean Seberg and John Lennon were targeted too, as Benedict Andrews glossy biopic Seberg and David Leaf’s The US vs John Lennon show. As I said on this site in a review of Göran Olsan’s film The Black Power Mixtape, it’s impossible to gauge the extent to which the FBI penetrated the Black Panthers, but there's no question that every invented technique of sabotage was used against them: bombings, defamation, disinformation, forged letters, harassment, infiltration, informants, intimidation, 'provision' of drugs, smears, spies, and psychological warfare. Those whom the Feds would destroy, they first make mad. Those whom they fear, they assassinate.

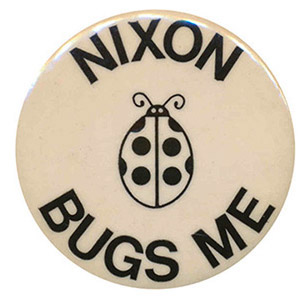

The FBI exploited existing divisions within the Black Panther Party as efficiently as they did divisions within the wider Black Power movement and the New Left. As Kathleen Cleaver says in Sam Green and Bill Siegel’s film The Weather Underground, ‘Once Richard Nixon was elected President and inaugurated in January 1969, we were targeted – bam, bam, bam – by a very sophisticated, advanced counterintelligence programme; at the same time, by very crude and violent police’. Nixon, having run to the left of Kennedy in 1962, ran on a law and order ticket against Wallace and Humphrey in 1969, but he sure wasn’t shy of breaking the law or afraid to set his Rottweiler Metzgerhund, Hoover, loose. Trump is already playing the law and order card with an eye on the November Presidential elections and he’s not afraid of setting either dogs or the Feds loose on Black Lives Matter protestors.

| The Rise And Fall Of A Statue |

|

A final word, in closing, on the matter of statues. On the 4th of May, 1886, thousands gathered in Haymarket Square, Chicago for a peaceful rally in support of workers at the McCormack factory, who were on strike for the right to an eight-hour working day. Police and Pinkertons had attacked a peaceful gathering at the factory the previous day, leaving one worker dead and scores injured, so feelings were running high. At the Haymarket Square rally, an unknown individual threw a bomb at police lines, killing several of them. The police responded by opening fire on the crowd, killing several protesters. Foreign radicals and outside agitators were blamed for the incident and eight innocent men were arrested. One was acquitted, three were executed, one committed suicide, and the surviving three were subsequently pardoned. In 1889, a statue was erected to commemorate the Chicago police whose brutality had precipitated the Haymarket Affair.

The new statue depicted a policeman with his right arm raised in an approximation of a Nazi salute. In 1927, a transport worker drove his tram into the statue, saying he was ‘sick of seeing that policeman with his arm raised’. In May 1968, at an anti-war demo just a week after the Columbia occupation, the statue was splattered with black paint. On the 6th of October 1969, the Weather Underground blew the statue up. On the 4th of May 1970, a replica of the same statue was unveiled. On the 6th of October that same year, the Weather Underground blew the statue sky high again.

In 1972, the Weather Underground warned that the stature would be attacked again so it was moved indoors, to within the Central Police Headquarters. In 1976, it was moved further out of sight, to a compound in the Chicago Police Academy. It might be better housed in a museum, with contextualising information about its chequered history. It might be even better to erect a statue to those workers who fought for the eight-hour working day the lucky ones among us now take for granted.

A 2016 report publishing in the American Journal of Public Health found that black men were three times more likely to be killed by the police than white men. One in three black men are incarcerated at some point in their lifetimes compared to one in 17 white men. Commenting on those findings, the journalist Oliver Wiseman wisely says, ‘Unpicking this knot is so difficult because, as both the police’s fiercest critics and most loyal defenders will agree, police killings of African-Americans are the most violent expressions of a thicket of social, cultural and economic problems surrounding race, poverty and violence in the United States’. Much the same could be said of the equally disunited United Kingdom. I hope I’ve at least hinted, above, what some of those problems are and what previous period of accelerated political and social change might teach us about possible solutions.

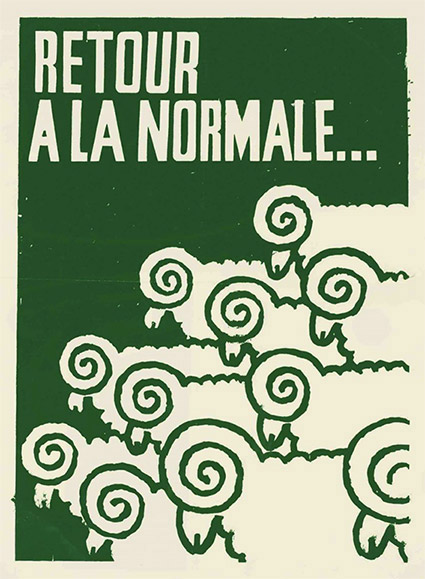

In The Long ’68: Radical Protest and Its Enemies, Richard Vinen suggests that the fragmented but unexhausted energies and ideas of 1968 rolled on long after the return to normal. They certainly made themselves felt long after Peter Whitehead had headed to the Sahara. So, too, did the spirit of ’45 and the popular political projects it forged, which resurfaced during the pandemic, long after Priestley shuffled off his mortal coil. In the eighties, both progressive currents trickled to a halt, drained of life by the conservative counter-revolution that ushered in market Stalinism and the billionaire class. Introducing a reprint of the socialist-feminist classic Beyond the Fragments, Sheila Rowbotham recalls the difficulties activists of the Occupy movement had comprehending the book’s central argument. Its references to the history of the left, she says, belonged to a broadly shared radical culture that has faded from view. The Black Lives Matter protests have energised a new generation of activists who may right now be rediscovering that dormant culture.

The early signs suggest the changes prompted by their protests are more likely to be symbolic than systematic, initially at least. ‘Each generation’, said Franz Fanon, ‘must discover its mission, fulfil or betray it, in relative opacity’. The protesters are predominantly young so strategic mistakes are inevitable, but their protests may merely be the opening exchanges in a struggle from which we’ll all learn. I tend to believe, as John Lennon did, that ‘our society is run by insane people for insane objectives’ and I’d fantasised that the pandemic might precipitate a popular revolution of values, a general awakening and a great reckoning. The early signs suggest we’ll need to be patient while awaiting a re-think or re-set. Plus ça change, plus c’est la même chose. Despite the shock to the system delivered by the pandemic, the ‘new normal’ looks uncannily like the old abnormal. Few, though, expect those who, and that which got us into the mess of the moment to guide us out of it.

J.B. Priestley titled the third section of his above-mentioned memoirs, Margin Released, ‘I Had the Time’. He notes that hundreds told him they could write a novel, play or book of essays – if they only had the time. Some wit once said that most people have a good book in them, and in most cases that’s exactly where it should stay. Priestley had the time to write and wrote some of the most beautiful books of his age. Time alone will tell if the pandemic generated a profusion of literary talent or a revolution of values. One thing’s for certain, many have begun to think, for the first time, about the cultural, economic, environmental, political and social crises we face.

That alone seems grounds for optimism, especially if you take the long view of politics. Millions may already be thinking along the same lines as Phil Ochs, who found time before he died to write: ‘I won’t be laughing at the lies, when I’m gone/And I can’t question how, or when, or why when I’m gone/Can’t live proud enough to die when I’m gone/So I guess I’ll have to do it while I’m here’. The politics of hope is on the move again and there’s a world to win, to rescue and rebuild.

PART 1 | PART 2 | PART 3

|