"Keep

a clear head and always carry a light bulb." |

Bob

Dylan's 'real' message |

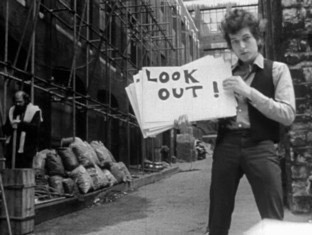

If there's a more exhilarating, iconic and trend-setting opening sequence to a documentary feature than the one that kicks off Dont Look Back, D.A. Pennebaker's remarkable film record of Bob Dylan's 1965 English tour (his last as a solo performer), then I've yet to see it. You may never have even heard of the film, but I can guarantee that if you were presented with this sequence then a very large proportion of you would let out a head-tipping "Ooohhhh" of recognition. It has been imitated, parodied, even adapted to sell Memorex audio cassette tapes, and remains the supreme example of the minimalist music video par excellence, despite being made some years before music videos were a thing, and not intended as a promotional tool to sell a tie-in album. Set to Dylan's Subterranean Homesick Blues, it features the singer standing in an alleyway holding up a stack of A3 sized cards bearing specific words from the song and peeling them off as it progresses, the words on the cards timed to match the lyrics as they are sung. If my description is even halfway on the nose then many of you will be making that "Ooohhhh" noise right now. It's such a simple idea, but proves a great way to kick off what remains to this day one of the very greatest rock documentaries in cinema history.

D.A. Pennebaker started out as a mechanical engineer and was instrumental in helping to create the portable film equipment that became essential to the birth of Direct Cinema and Cinéma Vérité. He began making short, inventive documentary works in 1953 with Daybreak Express, and like fellow directors-to-be Richard Leacock and Albert Maysles, he crewed for Robert Drew, one of the movement's godfathers, on the 1960 Primary and the 1963 Crisis: Behind a Presidential Commitment. But his real break came in 1965 when he was approached by Bob Dylan's manager Albert Grossman with the idea of making a film about the singer's upcoming tour of England. Pennebaker, though knowing little about Dylan, recognised the potential in the project and saw it as an opportunity to make his first made-for-cinema documentary feature.

Movies about musicians can be divisive in a way that few other films are, prejudged on the basis of musical taste that can exclude them even from viewing consideration because of who they are about. Thus a portion of the potential audience here is going to see the words Bob Dylan and engage their automatic bypass mechanism. Which would be a real shame, as although a record of a concert tour, this is no concert movie – Pennebaker includes only as much or as little of a song as each scene needs, letting a couple run almost for their entirety but cutting away from others after only a couple of bars. The focus of the film is not Bob Dylan in concert but how this young musician copes with the pressures and responsibilities of fame. That he does so with almost unwavering good humour is one of the film's most pleasant surprises – there are none of Elton John's colourful tantrums, no sign of the soul searching and ego-battles of Some Kind of Monster, and there's an earthy honesty that the likes of In Bed With Madonna can only dream of.

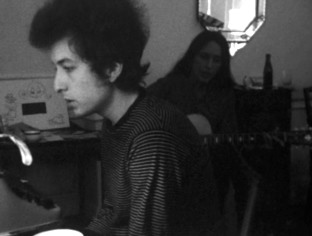

Nonetheless, an appreciation of Dylan the writer and performer will inevitably enhance your enjoyment of the material here. Footage of Dylan rehearsing, warming up for a gig, singing Hank Williams songs with Joan Baez, or (a rare sight) composing on a piano is valuable in itself, but it is his interaction with those around him that provides the film's chief fascination, in particular his dealings with the English press of the time. On a historical and cultural level alone this is extraordinary stuff, especially given the rise of youth-centred musical news reporting over the past thirty years. The reporters here – with their Middle England accents, formal suits and unimaginative questions – have no connection whatever to Dylan or his core youth audience, people a reporter from the Manchester Guardian somewhat sweepingly categorises as "bearded boys and lank-haired girls." The only reporter who seems genuinely interested in what Dylan is saying is the BBC's Africa correspondent, although despite having grown up in Jamaica he too speaks as if born to the gentry. A Time Magazine correspondent gets a particularly hard time and the only young reporter we see, who turns out to be a science student named Terry Ellis who writes for a university magazine (and was later to found Chrysalis Records), catches Dylan shortly before he is due on stage and in playful but unhelpfully argumentative mood.

Moments of conflict are rare – a problem with sound at one of the concerts, Albert Grossman rounding on a hotel manager who is complaining about the noise, Dylan losing his rag when one of his party throws a glass into the street from the window of his suite – and the film develops dramatically on moments of unity and collaboration rather than confrontation. On arrival in the UK, Dylan is initially bemused by the music press coverage of rising folk star Donovan – "I'd like to meet him," he remarks, and sure enough we later see Donovan in Dylan's hotel room playing a tune for an appreciative audience. A small group of fans gathered outside of Dylan's hotel in Manchester find themselves invited in to meet their idol and even Grossman is shown cooperating with tour promoter Tito Burns to up the price for a TV appearance, an interesting signpost to where the music industry was heading.

In common with many Direct Cinema works of the time, the film was shot on high grain 16mm with equipment Pennebaker himself had helped to develop. There is a roughness to the image and at times the camerawork (content was clearly more important to the director than any visual polish) that still looks edgy today, but which gives the film an immediacy and intimacy that gets us so close to Dylan and his crew at times that we can't help but feel part of his troupe, and we thus tend to see those he meets very much through his (and Pennebaker's) eyes. Mind you, given the somewhat stuffy nature of the establishment figures he encounters, his youth, talent, humour and intelligence make him an easily likeable figure and an inspirational reaction to a very conservative establishment. On the commentary track, Dylan's friend and tour manager Bob Neuwirth notes that even during the shoot they became aware that Pennebaker was doing with film what Dylan was achieving with music, bringing something new and energetic to a format that had fallen into mediocrity in the hands of establishment figures. It comes as little surprise to hear that when Pennebaker took the finished film to Warner Seven Arts in search of a distribution deal, they were dismayed at what they felt was the film's technical shabbiness. Boy must they have been kicking themselves when it went on to become one of the most commercially successful documentary features of all time.

But the film remains most precious for its off-guard moments, the scenes where Dylan and his friend Bob Neuwirth lose their awareness of the camera (Neuwirth does admit that the two played up for the film crew at times), and a superb sequence in which Joan Baez sings an achingly beautiful version of Dylan's Percy's Song while Dylan taps away an old typewriter, pausing at one point just to sit and listen and gently bob to the music. It's a captivating scene, and yet it contains no dialogue, little in the way of obvious emotional response and it's all done in a single hand-held shot, and like the final image of Paul in the Maysles brothers' Salesman, it speaks volumes about the subject in the very quietest of voices.

| sound and vision |

Shot on high speed 16mm stock in available light, the print here is high on grain and on contrast and a little fuzzy on fine detail, but black levels are good and tonally this is a solid transfer. Detail is not too hot in darker areas, but this could well be an issue with the original print, given that the conditions of filming were almost never ideal. Dust and dirt are evident throughout, but are not too bad and certainly not excessive given the film's age and low budget 16mm origins. Occasional flickering is caused by fluorescent lighting and even the camera battery running low, and is thus no fault of the transfer. On the whole, a very decent job that it would be hard to improve upon, given the source material. The picture is framed in its original aspect ratio of 1.33:1.

The Dolby 2.0 mono soundtrack is inevitably limited by the filming conditions and the low budget, but restrictions aside it's a reasonably clean job in which dialogue is always clear and the music reproduced as well as can be expected. The condisitions under which Pennbaker was forced to operate ensure that the camera motor is sometime audible, but given the spontaneous, do-it-yourself nature of Direct Cinema, this in no way detracts from the on-screen action.

| extra features |

Chief among the special features has to be the audio commentary by director D.A. Pennebaker and Dylan's friend and tour manager in the film, Bob Neuwirth. Though not quite as rich in detail as the one on Criterion's disk for Salesman, this is nonetheless really valuable stuff, providing background information on how the film and the tour came about, on the equipment used, on Pennebaker's approach to the project, and his relationship with the people he was filming. The two even send up the immediacy of Direct Cinema at one point, joking about how many takes it took to get a scene right and what a pain it was to light, as a very spontaneous and obviously unlit scene plays out on screen. Pennebaker comments on the importance of the lightweight camera and crystal-sync sound to the film, and made me laugh out loud with when he described his tension at the film's second screening for Dylan with the phrase: "I was chewing a hole in the seat with my rectum." There are a few small pauses in the chat here and there, but the two men bounce well off one another, and this is a very engaging and informative companion to the film.

Bonus tracks consists of five complete audio tracks recorded during the making of the film. All have been remastered for this DVD and are very clearly and cleanly reproduced. The tracks are: To Ramona, The Lonesome Death of Hattie Carroll, Love Minus Zero/No Limit, It Ain't Me, Babe, and It's All Over Now, Baby Blue. For Dylan fans, this is something of a treat.

The film trailer (1:47) is very simply the opening Subterranean Homesick Blues sequence with a bit of text at the end.

The "Subterranean Homesick Blues" alternate take (1:51) is exactly that, the opening card-dropping scene shot in an alternative location, but still with Bob Neuwirth and Alan Ginsberg in the background, though this time Ginsberg does a slightly distracting clothing change. A very valuable extra.

Profiles provides brief biographies of Pennebaker, Dylan and photographer Daniel Kramer, abridged filmographies and discographies for Pennebaker and Dylan respectively, and Pennebaker's own brief profiles of some of the cast and crew.

| summary |

Dont Look Back (and yes, in case you're wondering, there is no apostrophe in the tile) is a key work of American Direct Cinema and a prime example of the rock documentary at its finest, and although Neuwirth confesses that he and Dylan stage managed some of the action, there is just as much here that is honest and spontaneous. As a record of the man and the times it remains invaluable, as documentary cinema it is enlightening, compelling and always entertaining. A hugely influential piece – almost all subsequent rock documentaries owe a debt to the film – its shadow extends beyond the documentary genre into advertising, music videos and even fictional features, most notably Tim Robbins' witty and scary political satire Bob Roberts, which borrowed much of Dont Look Back's structure and parodied several of its more memorable scenes.Docurama's DVD features a solid transfer, an informative commentary track and a couple of nice bonus features. A must for documentary fans and Dylan enthusiasts alike