"The People is the grand canyon of humanity and many many

miles across / The People is a Pandora's box, Humpty Dumpty, a

clock of doom and an avalanche when it turns loose / The People

rest on land and weather, on time and the changing winds / The People

have come far and can look back and say: We will go farther yet." |

Carl Sandburg, The People, Yes, 97 |

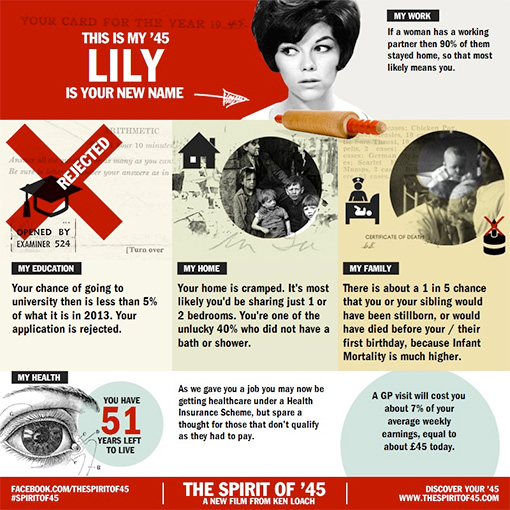

Few films have arrived with such perfect timing as The Spirit of '45; seldom do films so immediately and urgently respond to unfolding events. When it was released in cinemas in March, Loach's film presented a necessary cinematic corrective to Phyllida Lloyd's execrable biopic, The Iron Lady (2011). In the intervening months, it has also offered implicit criticism of iniquitous legislation enacted by the current coalition government: the introduction of the 'bedroom tax' and commissioning in the NHS, the scrapping of disability allowance and the 50p top tax rate for the rich, the capping of welfare benefits, and cuts to legal aid. The Spirit of '45 bristles with a sense of anger that so much is being taken from those least able to afford it and so little asked of the few with most to give.

Since Margaret Thatcher's death on 8 April, The Spirit of '45 has also operated as an unwitting intervention in the cursory debate about her legacy. Loach clearly intended the film as a critique of Thatcherism and an argument in defence of the NHS. He cannot have guessed its importance as a ready response to the establishment's coercive attempts to canonize her, manufacture a new national consensus around her memory, and detoxify her draconian politics. The Spirit of '45 speaks for the silenced majority whose lives and communities were blighted by Thatcherism and for those pained by the searing sight of history being rewritten before their eyes.

Ken Loach's last film, The Angel's Share (2012), was a delicious yarn about four working class Glaswegians who expropriate a quantity of rare malt whisky, with our blessing, and live happily ever after. In The Spirit of '45 he distills half a century of history into a similarly warming tale of wealth redistribution, albeit one that has no happy ending and leaves a bitter aftertaste. Loach's deeply moving and feisty polemic combines black and white archive footage, 'eyewitness' interviews, sound recordings, and song to take us on a partial journey through the ideas that shaped postwar Britain. It reminds us of the abject poverty of the 'hungry thirties', which strengthened the case for democratic socialism and lead to the Beveridge Report; of the spirit of solidarity, mutual respect and collective strength that had solidified under conditions of wartime adversity and which underpinned the prevailing view of common ownership as common sense; and of the enthusiasm for radical change that culminated in the Labour Party's unprecedented landslide victory of 1945.

John Campbell, author of The Iron Lady (the book on which the film was based) and the biography Nye Bevan, accused Phyllida Lloyd of over-simplifying history. Given the ground Loach covers, it is inevitable that he does so too. As Ian Jack said in his piece of the film in The Guardian: "(Loach's) story has three simple acts. Working-class people were unhappy, then they were happy, then they were unhappy again." He dashes through history as if racing Brasseur, Frey, and Karina through the Louvre in Godard's Band à part. It is to be regretted that he didn't pause to mention Empire and Indian independence, a clear commitment of the Attlee government. It is also a shame that Loach didn't mention, if only in passing, the earlier achievements of municipal socialism, which transformed working class life and bequeathed us a network of parks and hygienic sanitary conditions. For those who believe that documentaries should educate and inform, it is particularly unfortunate that Loach sets education aside. The Butler Act, Jenny Lee's Open University, and libraries (the universities of the people) surely deserved substantial space.

Loach doesn't linger long on detail, which he sacrifices to punchy, persuasive argument. After delineating the construction of the welfare state up until the 1951 Festival of Britain, Loach skips three decades to the twist in the film's tail: Margaret Thatcher's election in 1979 and his argument that, in dismantling the post-war settlement and re-establishing pre-war levels of inequality, Thatcher contravened the wishes of the generation that defeated fascism. Despite its title, then, The Spirit of '45 is a tale of two years: 1945 and 1979. It is also a tale of two classes: the working class and the ruling class. Loach has persistently encouraged audiences to take sides; here he is typically partisan and polemical. Beneath the film's calm surface broils indignation at the inhuman conditions endured by the pre-war generation and disgust at the way the ameliorating social support systems established after 1945 have been systematically destroyed, and by the beneficiaries of social progress at that. The last time the best-off took as big a share of all income as they do today was in 1940, two years before the publication of the Beveridge Report, which dovetailed with the push for socialism and became the basis of the welfare state. Brecht famously asked: "In dark times/Will there also be singing?" Loach's film is largely in tune with Brecht's rhetorical reply: "Yes, there will be singing/About the dark times." The Spirit of '45 is simultaneously a hymn in praise of political possibilities, a sing-a-long pop song celebrating what we once were, a bluesy ballad lamenting what we've lost, and an angry riff on what we've become.

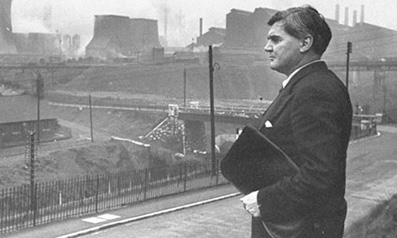

In its opening stages The Spirit of '45 seems to imagine a letter from Clement Attlee to Abraham Lincoln communicating the good news that the idea of 'government of the people, by the people, for the people', far from having vanished from the world, was finally taking shape in Labour's 'New Jerusalem' and being built upon the ruins of Britain's bomb-damaged cities and slums. The film initially feels like a disquisition on the achievements and inadequacies of parliamentary socialism; with particular attention paid to its most momentous electoral triumph (in which it won just under 50 per cent of the popular vote and a majority of 146 seats), its greatest hero (Nye Bevan, who Attlee shrewdly appointed Minster of Health with responsibility for housing), and its crowning glory (the National Health Service, free to all at point of use, on the basis of clinical need not ability to pay).

The NHS was at the heart of Labour's election campaign, and it is at the centre of Loach's film. One of Loach's interviewees reminds us that it wasn't just the Tories who were hostile to the establishment of the NHS; Nye Bevan was only able to overcome the resistance of GPs and their representative body, the British Medical Association, by "stuffing their mouths with gold." Bevan said: The collective principle asserts that . . . no society can legitimately call itself civilized if a sick person is denied medical aid because of lack of means," particularly a society with the resources of Britain, which Bevan called, "an island of coal, surrounded by fish." Loach's politics lie closer to those of Nye Bevan and Tony Benn than to those of Ernie Bevin and Tony Blair, so he is not uncritical of the Labour Party. He certainly emphasizes one of Labour's most significant failings: the paternalism and lack of industrial democracy stitched into its programme of nationalizations. He is, though, sympathetic to Labour's achievements.

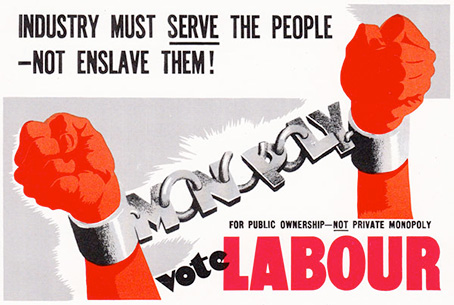

The sharing and shared suffering of the war had increased the appetite for a better-planned, more egalitarian society that would ensure full employment and improved social benefits for all. One of the more startling moments in the film occurs during the 1945 election, when a crowd boos Churchill and begins chanting "We want Labour! We want Labour!" Churchill's warnings to the electorate not to be 'hoodwinked' by the apparent reasonableness of Labour's leadership fell on deaf ears and his attempts to scare them by associating Labour's democratic socialism with the Gestapo blew up in his face like a toy cigar. Labour rose above such negative campaigning. They vigorously rejected Churchill's assertions, arguing that it was only a democratic socialist government that could bolster personal freedom while providing an effective challenge to monopoly power and unregulated capitalism. Out on the campaign trail, Churchill told Clem Attlee: "I've tried them with pep and I've tried them with pap, but I still don't know what they want." A 1945 Gallup poll showed that 'Housing' topped the list of the electorate's preoccupations with 41 per cent, followed by 'Full Employment' at 15 per cent, 'Social Security' at 7 per cent, and 'Nationalization' at 6 per cent.

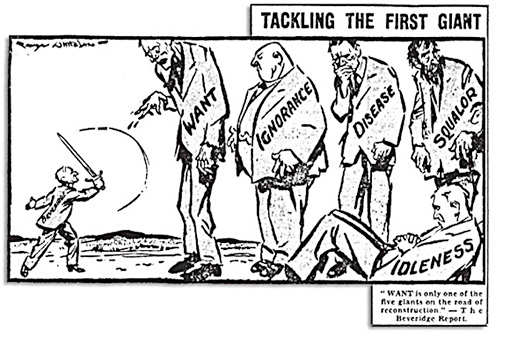

If the electorate may not have been collectively clamouring for Socialism red in tooth and claw, socialist planning was widely accepted as the basis of economic recovery from war. The public certainly wanted Labour to attack Beveridge's 'five giants': Disease, Ignorance, Idleness, Squalor, and Want. J.B. Priestly - whose plays, novels, and wartime radio broadcasts helped pave the way for Labour's landslide victory, wrote of the Northern towns he considered the industrial backbone of Britain: "If Germans had been threatening these towns instead of Want, Disease, Hopelessness, and Misery something would have been done quickly enough." One of those interviewed by Loach, retired GP Julian Tudor-Hart, recalls the determination with which people said 'Never again', to the inequality of the inter-war years, a time when "everything was run by rich people for rich people." Then, as now, a dual crisis of capitalism and liberal democracy demanded an authentic progressive response to the continuing failure of fiscal and monetary orthodoxy to combat acute social deprivation. Loach's reminder of the radicalism of Labour's programme often screams with contemporary relevance, particularly when he quotes from Labour's 1945 election manifesto, Let Us Face the Future:

"In the years that followed (the First World War), the 'hard-faced men' and their political friends kept control of the Government. They controlled the banks, the mines, the big industries, largely the press and the cinema. They controlled the means by which the people got their living. They controlled the ways by which most of the people learned about the world outside . . . The great inter-war slumps were not acts of God or of blind forces. They were the sure and certain result of the concentration of too much economic power in the hands of too few men. These men had only learned how to act in the interest of their own bureaucratically-run private monopolies, which may be likened to totalitarian oligarchies within our democratic State. They had and they felt no responsibility to the nation. Similar forces are at work today." *

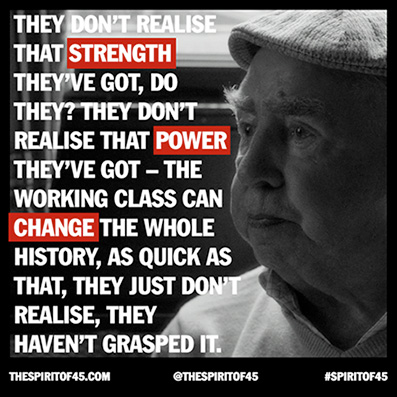

Loach's work is all too often damaged by his tendency to dry didacticism but, in this formally conservative tearjerker, his judicious decision to foreground the experiences of the citizenry rather than the views of the commentariat brings his arguments to life. The Spirit of '45 bears the subtitle 'Memories and Reminiscences', and much of its force derives from the dignity, eloquence and insight of those who discuss the changes the welfare state made on their lives. At the film's very human heart are the testimonies of veteran postal, steel and railway workers; dockers, doctors and nurses; teachers and miners.

Among the most moving is that of former shop steward, Sam Watts, who emphasizes the demand for social justice, specifically the crying need for decent health care and housing, that was met by Nye Bevan and the Labour government. Watts speaks for millions in his pre-war generation when he describes the appalling conditions he grew up with in Liverpool, as the third of eight children – conditions that claimed the lives of several siblings, each buried in a pauper's grave. 87 year-old Watts says: "We were the greatest empire in the world and we were living in the worst slums in Europe . . . We got into bed of a night with a bed full of vermin . . . the bugs, the fleas were in hundreds, in the beds . . . behind the wallpaper, in the skirting boards . . . and when we went to school, we got the cane for having dirty knees."

Another interviewee, retired nurse Eileen Thompson, grew up in the same era, in the same great port city, and in similarly deprived circumstances. She remembers the fine-line struggle for survival without bitterness, even with a hint of wistful regret for the passing of a fragmented sense of social solidarity: "We had to go to bed early, to keep warm, it was the same for everybody . . . people did manage, but it wasn't easy . . . every Monday morning the women would take their bundles up to the pawn shops in the city area . . . and the tram conductor would say . . . 'Daglish's next stop. Brown's are giving a good price today Ladies'. It was fun really . . . when it got to the terminus, he'd say: "All the way! Poverty Park!"

Many living in today's Britain would recognise such pawn-shop, make-ends-meet poverty, but so little mention is made today of such squalid social circumstances, and so rarely do we listen to that generation of which Sam Watts and Eileen Thompson are emblematic, that many viewers may find it hard to believe their ears as they listened to such eyewitness accounts. Working from the principle that 'seeing is believing' Loach provides prodigious visual evidence to support their accounts, drawing extensively on material bequeathed by the documentary movement.

Loach has cited Ewan MacColl, Charles Parker and Peggy Seeger's legendary Radio-Ballads as a significant influence on his film. Made for the BBC between 1957 and 1964, those aural documentaries combined interviews with music and sound recorded in the field to create poetic portraits of working class life. Another evident influence on the film is Terence Davies's Of Time and the City (2008), which was itself influenced by the lyrical wartime documentaries of Humphrey Jennings. Like Davies's film essay, Loach's owes much to archive researcher Jim Anderson's skill at collating images from the documentary tradition: in the former Anderson deployed footage from films of the 60's and 70's [notably extracts from Nick Broomfield's Liverpool documentaries Who Cares? (1971) and Behind the Rent Strike (1979), in the later he draws primarily on the newsreels and documentaries of the 30's and 40's – notably on Arthur Elton and Edgar Anstey's Housing Problems (1935).

Like Davies's film, and like Penny Lane's Our Nixon, Loach's latest is a documentary built from documentaries; a welcome addition to the growing sub-genre of archive-based documentary. Just as archive-based film essays such as the above-mentioned fuse film present and film past while pointing to film's future, so The Spirit of '45, which Loach describes as 'a resource for the future' uses the lessons of history to reflect on contemporary concerns. Unadorned, undiluted fact is as needed now as free, unfettered imagination and fearless experiment, so, if the film suffers from a certain stiffness due to being too tightly bound to convention, no matter; what the film says is more important than how it says it.

Such is Loach's interest in the whys and wherefores, what-ifs and what-might-have-beens of history that it seems apt to end with a few that apply to him. Those who have come to expect a film every year or two from Loach, all too easily take him for granted. It is hard to imagine our film culture or politics without him. Had the BBC not provided him with an auspicious start in television in the 1960's, he might not have gone on to become one the world's most prolific and respected film directors. Loach cut his teeth during a golden age of TV drama, when ABC's Armchair Theatre and the BBC's Wednesday Play nurtured gifted (often fiercely socialist) mavericks like Alan Clarke, Alun Owen, Alan Plater, David Mercer, Tony Parker, Mike Leigh, and Loach himself. Had he not been in the right place at the right time, had he not been fortunate to cross paths with Tony Garnett at the start of his directorial career, and had Jim Allen not politicized him, things may have been different. It is conceivable, particularly given his early thespian experience with the Oxford Revue and Northampton rep, that he might have drifted into theatre instead. It is equally easy to imagine Loach as a teacher; he certainly looks and acts the part. Had he opted for a career in education, history would surely have been his subject.

History has certainly been Loach's subject as a film director, most obviously in the historical dramas that have punctuated his career: in his four-part TV series Days of Hope (1975) he covered the period between the First World War and the General Strike, in Land and Freedom (1995) he reprised the arguments about the Spanish Civil War presented in Orwell's Homage to Catalonia, and, most recently, in his Palme d'Or winner The Wind That Shakes the Barley (2006), he bravely and single-mindedly concentrated on the Irish War of Independence and subsequent Civil War.

Loach has also produced a running commentary on the controversies and conflicts of more recent times. Throughout a career spanning half a century, Loach, alone among his contemporaries, has consistently and assiduously addressed significant moments of political promise and rupture, as and when they occurred, covering industrial disputes otherwise largely or completely ignored. In The Rank and File (1971) he looked at the 1970 St Helens Glass Workers' Strike, in first The Big Flame (1969) and then The Flickering Flame (1996) he covered the respective Liverpool Dockers' Strikes of 1967 and 1996, and in Questions of Leadership (1983) he documented the wave of defensive strikes precipitated by Thatcher in the early 80's. He also, of course, considered the decisive defeat of the 1984 Miners' in Which Side Are You On? (1985), which is included, along with a wealth of recorded interviews, in the extravagant extras on Dogwoof's excellent DVD release of The Spirit of '45.

Whether making films for television or cinema, whether working in documentary or fiction (or, more often, merging all four forms), Loach has recorded his times with dogged persistence and forensic precision, always talking truth to power. No director has so consistenly retrieved those aspects of our history cynically erased by power, no director has so forcibly disputed 'official' versions of the recent past, and few directors have so regularly placed emblematic, under-represented working-class characters on screens large and small. Even Loach's dramas - from Cathy Come Home (1966) and Kes (1969), through Riff-Raff (1991) and Raining Stones (1993), to The Navigators (2001) and Looking for Eric (2009) – add to the sense of Loach's oeuvre as a documentary account of the post-war era that acts as a counterbalance to the organised forgetting, doublespeak, and disinformation of the dominant culture. The Spirit of '45 is an important reminder of a period in our island history of which we hear too little, too rarely. For that we should be grateful.

As I have said elsewhere, Chris Marker ends his political masterpiece Le fond de l'air est rouge/A Grin Without a Cat, (1973) with an unforgettable scene in which he cuts from an international arms fair to found footage of the culling of wolves by snipers in helicopters. It is a moving metaphor, a memorial to those free spirits who fought for liberty, equality and human solidarity. The film's final words are: "A comforting thought ... some wolves still survive." Loach is one of Marker's wolves; a rare, untamed survivor, still roaming the plains of contemporary cinema, still bearing his teeth, still dangerous, still capable of going for the throat.

* http://www.labour-party.org.uk/manifestos/1945/1945-labour-manifesto.shtml

|