|

Penny Lane's Our Nixon was made for a minute fraction of the $44 million spent on Oliver Stone's Nixon (1995) and the $25 million spent on Ron Howard's Frost/Nixon (2008). Despite being made for less than even the more modest $350,000 spent on Robert Altman's Secret Honor, Lane's contribution to Nixoniana more than holds it's own in such exalted company. Her compelling archive-based documentary adds enormously to earlier insights into Nixon and the period between his inauguration in 1969 and forced resignation in 1974. Testimony to how far commitment and imagination can stretch, Our Nixon is beginning to reap its just rewards. It earned rapturous applause when it received its international premiere at Rotterdam in January, then went on to win the Best Documentary award at Seattle earlier this month. Lane's compact but complex portrait of the men behind the president behind the Watergate scandal seems sure to build on its early success after it screens at the Open City Docs Festival in London this weekend.

Lane's revealing peek behind the curtains of power is built around 204 reels of Super 8 home movies shot by three of Nixon's closest aides: Chief of Staff H.R. Haldeman, Assistant for Domestic Affairs John Ehrlichman, and Special Assistant Dwight Chapin – all of whom were ultimately imprisoned for their part in Watergate. This riveting footage of the Nixon administration at work and play was seized by the FBI during the Watergate investigation and subsequently deposited in the vaults of the National Archives. It lay dormant there for four decades until Lane's co-producer and ex-husband Brian Frye learned of its existence, in 2001, from film preservationist Bill Brand – who was working on 16mm blow-ups of the 8mm stock. After seeing the Super 8 footage, Frye peeled off to for a period of study (he is now a Professor of Law), but the films played on his mind and he vowed to return to them.

When Frye and Lane met in 2008, they immediately resolved to work together to make something – they knew not what – of this previously unseen material. It was clearly a labour of love for them both. They lived and breathed the film. Lane says: "It's what we did for fun, it's what we did for work, it's what we talked about at dinner." Their evening conversations must have been tense at times. They knew they had something special on their hands from the start, but they soon exhausted their own limited financial reserves developing the project. The film might never have seen the light of day or dark of a cinema but for a successful Kickstarter fundraising campaign, which lead to additional institutional backing. Their perseverance has finally paid off in a finished film that is as amusing and eye-catching as it is unsettling and thought provoking.

Cine enthusiasts to a man, Haldeman, Ehrlichman and Chapin filmed indiscriminately, for pleasure, and at the behest of vanity. Day in, day out during Nixon's two terms in office, they recorded events large and small, momentous and mundane; at intimate evening screenings they projected their understandable sense of self-importance to themselves, their families, their friends. Chapin was just 27 years old when joined the Nixon encourage, Haldeman just 34, and Ehrlichman not much older. As Ehrlichman says in the film, "It got to be very heady, very fast" The found footage reveals the camaraderie of a tight-knit group of driven men on the make, dedicated young professionals revelling in their good fortune and proximity to power. This is engaging in itself, but these are Washington insiders not 'average Joes' and these are no ordinary home videos.

Sharing Nixon's sense of historical destiny and infected by his ultimately fatal mania for documentation, the trio also filmed compulsively, with one eye on posterity. Haldeman's shots of Chapin, Ehrlichman and Henry Kissinger cavorting on the beach at San Clemente jostle with footage of visiting Heads of State – a rogues gallery that shows Nixon with the likes of Nicolae Ceausescu and Robert Mugabe. Their cameras were light and portable, so they carried them with them to the Kremlin and the Vatican on whistle-stop presidential tours of Europe, and to the Great Wall of China during Nixon's groundbreaking trip to meet Mao. We watch and wonder what the Pope must have made of Nixon, and what Nixon must have made of his visit to a Red Women ballet depicting the overthrow of a landlord by communist partisans. Such celluloid juxtapositions of the personal and the political are what makes Lane's film tick. The footage amounts to a tour of their lives and their unusual world. Small wonder that The New York Times described Haldeman's house as, "the only place in the United States where dinner guests don't come down with instant indigestion when the host enquires: 'Would anybody like to see some home movies?'"

Of course the three men unwittingly filmed innocently and ironically too, with no idea of the precipice over which their ambition and blind loyalty would push them and no notion of how history would maul them. Knowing how things will end, we're pinned to our seats by a Hitchcockian sense of suspense; by morbid curiosity, voyeuristic compulsion and feelings of revulsion. The film introduces us to a happy band of bright-eyed, bushy-tailed conservatives, pulls back to show the cracks appear in the carapace of corruption, before zooming in on the political catastrophe that destroyed the three stooges and the president they served.

Although Our Nixon isn't about Watergate, it does build up a telling picture of that shameful episode and the events that ended, for the three aides at least, in betrayal, defensiveness, denial, and jail. Lane admits that her sympathy for the three men grew as she conducted her extensive research, but it is clear that she had a wider sense of betrayal in mind as she made the film. She says: "Haldeman, Erlichman, and Chapin put their faith in Nixon. They gave their lives to him and he treated them badly. To place one's trust in somebody and have it betrayed. It's just so heartbreaking. But, ultimately, who gives a shit about them? Well, I do, but it doesn't matter to the world. What matters is that it's symbolic. Their lost innocence was America's lost innocence."

Fascinating though the Super 8 footage is, that material alone wouldn't be sufficient to carry the film. An equally vital ingredient in its composition is the Nixon White House tapes, an element of the surveillance culture the paranoid president established and which turned out to be his Achilles' heel. Lane makes telling use of those damning voice-activated recordings, which reveal Nixon's three stooges to have been dedicated, eager to please, and willing to follow orders. Our Nixon is a minor masterpiece of intelligent, understated editing. Lane and Editor Francisco Bello seamlessly interweave the Super 8 material, newsreel clips, televised presidential addresses, additional found footage, and to-camera interviews with Haldeman, Ehrlichman, Chapin. Supervising Sound Editor Tom Paul then layers that lustrous material over excerpts from the White House audiotapes, blends in Hrishikesh Hirway's delicate original score, and surrounds the whole with light, lilting pop from the period.

The music in the film is often as lush as the Super 8 footage it draws on. On a blog devoted to his own self-penned pop, Frye says, "a little twee goes a long way" In Our Nixon it certainly does. The film is beautifully bookended by Tracy Ullman's sugary cover of Kirsty McColl's 'They Don't Care About Us' and Barbara Foster's schmaltzy "San Clemente's Not the Same" – a Nimby protest song about the sequestration of San Clemente (the 'Western White House) by Nixon's entourage which contains the repeated chorus 'Mr Nixon You're To Blame'. Lane says: "We wanted to use The Carpenters but we couldn't afford to license it . . . so we aimed for orchestral covers of The Carpenters."

One of the many extraordinary moments in the film occurs when Nixon introduces light entertainment act The Ray Conniff Singers at a social occasion. After Nixon leaves the stage (having declared, "If the music is square, it's because I like it square") two female Singers stage a pre-arranged anti-war protest. Their speech falls on deaf ears. At any rate, it is delivered to a silent, presumably stunned, perhaps overly polite audience. The group then perform a deliciously syrupy version of 'Ma! He's Making Eyes at Me'. It is a heartening reminder that even squares can dig peace. Lane says: "We were trying to explore square America. I grew up in a world in which Nixon was seen as a monster and Daniel Ellsberg is a hero, period. It's the only narrative I ever had. When you watch most films about that period it's as if everyone was burning their draft cards and listening to Janis Joplin, Jimmy Hendrix and . . . Creedence Clearwater Revival. I'm just trying to remind people that it was a counterculture."

Although the film's mood is occasionally dark, particularly in its final third as its focus shifts to Watergate, the dispiriting gloom is leavened not only by discordantly jaunty music but also by regular flashes of humour. In a conversation as chilling as it is funny, the 37th President of the United States discusses popular TV programme All in the Family, an adaptation of the British sitcom Till Death Do Us Part that revolves around a 'lovable' working class bigot who must have reminded Nixon of his beloved 'hard hats'. Nixon berates the programme for what he deems its promotion of homosexuality. He argues that it was homosexuality that destroyed Greek civilization and concludes by saying: "That's why the communists and left-wingers are pushing it. They're trying to destroy us." That stark reminder of Nixon's paranoia, and of the continuity between the McCarthy and Nixon eras, highlights the divisive nature of Nixon's politics.

Nixon polarized opinion in his time as dramatically as Margaret Thatcher did in hers. There are obvious parallels between the two leaders: both were born to grocers, both resented (while supporting) the idle rich, both cultivated the myth that they needed next to no sleep, both relentlessly beat the hollow drum of patriotism, both ruthlessly attacked their political enemies by any means necessary. Like Thatcher, Nixon inspired intense feelings of love and loyalty: the kind of loyalty which Haldeman, Ehrlichman, Chapin had for Nixon, and which he rewarded with betrayal; the kind of love the terrified U.S. electorate expressed when they returned him to the White House in 1972 with over 60 per cent of the popular vote and by the widest winning margin in the history of U.S. Presidential elections.

Nixon, like Thatcher, inspired equally intense feelings of hatred: the kind of hatred displayed by Sean Penn's Samuel Bicke in Niels Muller's The Assassination of Richard Nixon (2004) or by Kirsten Dunst's Betsy Jobs in Andrew Fleming's irreverent romp Dick (1999) – who shouts at Nixon: "You kicked Checkers, you're prejudiced, and you have a potty mouth." Perhaps nobody expressed visceral hatred of Nixon more eloquently than Hunter S. Thompson, who said, with characteristic pugnacity: "Nixon's entire political career, in fact his whole life, is a gloomy monument to the notion that not even pure schizophrenia or malignant psychosis can prevent a determined loser from rising to the top . . . If there was any justice in this world, his rancid carcass would be somewhere down around Easter Island now, in the belly of a hammerhead shark."

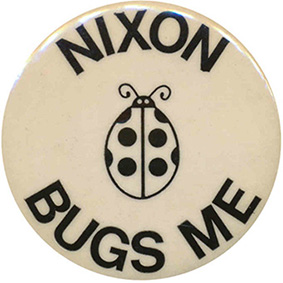

To his admirers Nixon was proud, upstanding 'Dick', to his detractors he was slimy, slippery 'Tricky Dicky', and worse. Lane doesn't take sides in that clash of ideas and invective. She says: "I don't have a bone to pick in this particular battle." I doubt she'd sympathize with Nye Bevan's observation that, "We know what happens to people who stay in the middle of the road. They get run down." But she has good reason to appreciate, as Nixon certainly did, what Henry Adams was driving at when he cynically suggested that, "Politics, as a practice, whatever its professions, has always been the systematic organisation of hatreds." When we discussed her "pro-choice advocacy piece" The Abortion Diaries, Lane said: "It was an attempt to approach a divisive issue and go beyond bumper stickers." Reaction to her film has divided down similarly partisan lines.

While many would position Lane within that current which Ehrlichman calls "fatal liberality," she seems determined to give Nixon a fair hearing. Lane is certainly sympathetic with Noam's Chomsky's view that Nixon – despite the cynical anti-black racism of his 'southern strategy', despite his rabid anti-semitism, homophobia, warmongering, and contempt for women – was among the most liberal of presidents. As Carl Freedman points out in his excellent book The Age of Nixon, Nixon ran to the left of Kennedy in the 1962 U.S. presidential election, federal spending on social programmes exceeded military spending for the first time on Nixon's watch, federal support for the arts quadrupled under his administration, and he presided over the Clean Air Act of 1970 and created the Environmental Protection Agency. Lane is not afraid of challenging "received wisdom" about Nixon or of ruffling left-wing feathers (this reviewer's are still settling down). She says: "All history is revisionist, it's a struggle between competing stories. It's still contested. It's still contestable." (this reviewer couldn't agree more).

Lane says: "As a naïve person who was born after Nixon's presidency, I used to think it was all about people on the left, that people like Daniel Ellsberg were his victims. Then I thought, 'No, that's bullshit. The people whose lives Nixon really ruined were his own supporters, people like Haldeman, Ehrlichman and Chapin'." Many would beg to differ. Many might mention African-Americans and point to the suffering of America's poor. Many might mention Nixon's indiscrimate Red-baiting, Red diaper babies, and McCarthyism. I suggest that her list of Nixon's frontline victims should be broadened to include Cambodians, Chileans, Vietnamese, and so on. Disarmingly, Lane concedes ground and says: "That's true. I admit a certain narrowness of focus on a watershed moment in America's domestic history. You can't please everyone. There were those who wanted Our Nixon to be an angry film. At Q&As people would say, 'Why haven't you included the Kent State Massacre? Why didn't you include Watts? Why didn't you include Pat Nixon? That's not the film we wanted to make. We had a more opaque film in mind. We didn't want to heavily 'editorialize'. We ask audiences to reach their own conclusions." Lane's comments are echoed by co-producer Brian Frye, who says: "We wanted Our Nixon to be the anti-Nixon film . . . or rather, I should say, the anti-Nixon-film film!"

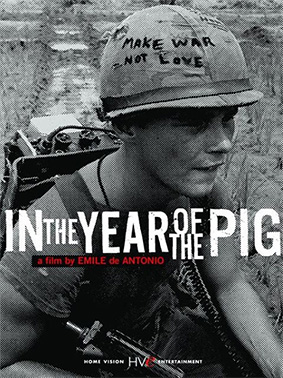

Lane's aesthetics are as open-ended as her politics. After seeing Our Nixon, I was surprised to learn that she and Brian Frye both list Emile de Antonio as a significant influence; surprised partly because Frye has said: "Anything that's about politics or a politically loaded subject, it's like there's something about making films like that that causes people to excise the creative part of their brain . . . propaganda has never been interesting." De Antonio's career suggests otherwise; his films prove that propaganda for peace and social justice can be interesting and inventive. Be that as it may, Lane and Frye have both worked as film programmers and appreciate de Antonio significance as one of the pioneers of archive-based documentary. While de Antonio's political commitment and aesthetic of "democratic didacticism" clearly has little appeal for them, they obviously share his fondness for "radical scavenging." It was only in the research phase of the film that Lane became aware of de Antonio's scathing Nixon film, Milhouse: A White Comedy (1971). She has, however, long admired both his McCarthy film, Point of Order! (1964), built exclusively from television footage of the 1954 Army vs McCarthy hearings, and his militant masterpiece In the Year of the Pig (1968), which combined archive footage, interviews and ironic use of music.

Our Nixon is a welcome addition to the growing current or sub-genre of collagist archive-based film that de Antonio helped to establish and which has so strengthened documentary film culture of late. Some of the finest films of the past decade have mined the archives: some have done so exploring the lives of extraordinary individuals – such as Asif Kapadia's Senna (2010) and Malik Bendjelloul's Searching for Sugar Man (2012), others have done so while exploring cities – like Terence Davies's Of Time and the City (2008) and Guy Maddin's My Winnipeg (2007), others again have used archive material while exploring politics – such as Eugene Jarecki's Why We Fight (2005) and Ken Loach's The Spirit of '45 (2013). Lane herself was determined to use only archive material, to avoid use of still images, and to steer clear of dramatic re-enactment.

Lane's faith in, and enthusiasm for archive-based documentary is infectious. She says: "I'm not interested in inventing things. I feel really strongly about archive work. It's not a trick or a gimmick. When you deal with primary sources, a certain kind of truth emerges that cannot come out any other way. I go into the archives without meaning in mind. The meaning is open-ended. Archival sources force you to think that way. The very first time the story of Watergate was mentioned on the news, it was like (she laughs) 'Here's this thing that happened over the weekend! Now here's the weather'. It's interesting to see how things become a story, how they become historical narrative. It's present tense and in the present tense there are no answers. You're dealing with film as it unfolds There are a couple of films that have come out recently that do that kind of thing: Göran Olsson's The Black Power Mixtape and Jason Osder's Let the Fire Burn. Archive research brings you into contact with the past in a different way. It's a way of understanding history and history is life."

Paul Robeson said: "Each generation makes its own history." Our Nixon reminds us that, while each generation must fight it's own battles, those battles are often those fought by their forebears. At one point in the film we see Daniel Ellsberg defending himself against accusations of treachery after he leaked the Pentagon Papers. The White House tapes of 14 June 1971 record Haldeman's breathtakingly prescient take on the furore surrounding Ellsberg's action: "To the ordinary guy, all this is a bunch of gobbledygook. But out of the gobbledygook comes a very clear thing: you can't trust the government . . . And the implicit infallibility of presidents, which is an accepted thing in America, is badly hurt by this, because it shows that people do things the President wants to do, even though its wrong – and the President can be wrong."

Fast-forward four decades to the age of googledygook and we find Daniel Ellsberg defending whistleblowers Bradley Manning and Edward Snowden against accusations of treachery. Manning is currently undergoing trial for 'aiding the enemy'. Snowden is in hiding after leaking U.S. State Department 'classified' documents detailing an alarmingly Orwellian degree of state surveillance. Lane says: "Here it is again. We want our governments to protect us from 'the bad guys' but we want them to do so without doing anything sneaky. Those issues are live." Knowledge is power, and documentaries like Lane's arm us with the knowledge of yesterday's battles we need to fight those of today. Our Nixon recalls the Turkish proverb that says, "Things never go so well that one should have no fear, and never so ill that one should have no hope."

|