"The single most important figure in the history of the American film and

one of the most influential in the development of world cinema as an art." |

The start of the six-page entry on D. W. Griffith in

Ephraim Katz's International Film Encyclopedia |

Wow. That is one hell of a statement from one of the world's most respected film reference tomes. He may not be way off the mark but there is the small matter of some appalling racial stereotyping and rampant racism in this astonishing work – so how do we judge the viability, shape and beauty of an original, exciting and newly designed bottle knowing what ugly poison sits inside? Bear with me while I briefly question the relationship between a time period and sin. The ex-BBC presenter Stuart Hall was sentenced to fifteen months in prison for child abuse offences throughout the 70s. The judgment was regarded as too lenient. The justification for such leniency was that he had been given the sentence as if he had been tried at the time of the offences. The casual and terrible inference in that statement is that raping and abusing children wasn't that big a deal in the 70s. It certainly seems now that a great many people were doing it. But complaints led to a doubling of the original sentence and so justice, of a sort, was done, 2013 style. Marcus Brigstock, a regular on BBC Radio 4, made a comical but spirited defence of the American right to bear arms. He wanted to add one small caveat; that the arms to be borne should be those that were available at the time of the writing of the amendment. I can't see the Columbine massacre being quite as horrific with Eric Harris and Dylan Klebold pausing to re-stuff their muskets with a ball and powder while teachers and students overpowered them. There is an eerie logic to Brigstock's idea, one that was applauded by his no doubt liberal-leaning audience. So, the sins of the past as judged by the culture of the future – is there a definitive answer to this nasty conundrum? My only response is to try and review the film as presented and then take some time to ruminate on how a filmmaker could almost scupper his own masterpiece with such an ill judged but personally held (dare I say) 'honest' point of view. That's his honesty, not mine. He admits in one of the Extra Features that he deeply believed in what he was portraying despite the inter-titles (the title cards that appear every time non visual information is required). They occasionally add their own 'get out of jail' card proclaiming that "This is an historical Presentation of the Civil War and Reconstruction Period and is not meant to reflect on any race or people of today." Oh, really? There would be no need for that inter-title if Griffith was innocent of the most appalling racial stereotyping of its time and ours and perhaps any time. He knew exactly what he was saying with his movie and he said it loud and proud with absolutely no equivocation. Good God, I almost admire the bastard.

Before we see a frame of the actual movie, we are treated to a series of inter-titles. Aside from an introduction to the story, they are proof – if any were needed – that Griffith had an ego the size of Kansas. Each inter-title bears his name and two sets of his initials and his name, initials or signature appear (count them) fourteen times on the first two cards alone. It makes the already absurd modern credit of 'A so-and-so film' look like rank under-achievement. So all that flummery aside, what's this revered (with reservations) classic actually about?

It's just before the start of the American Civil War. Slavery is the burning issue of the day and the northern white Stoneman family represents the abolitionist stance. The white Camerons epitomize the slave-owning families of the south, those living in an area that came close to removing itself from the governance of the United States politically speaking (seceding) over the slavery issue. The inter-titles seem to hark back wistfully to a time in the South when the status quo was actually one worth defending (this is the first sign that the filmmaker's sympathies may not be in line with current more enlightened thinking). Sons and daughters of both families fall in love and the war begins dividing friends and exacerbating racial and geographic conflict. There is the famous scene of Lincoln being shot by John Wilkes Booth whilst at the theatre (still damn effective after a century) with Joseph Henabery giving Daniel Day Lewis a run for his anti-confederate coin. After this event, both sides in the war seem rudderless. Lincoln was to oversee the enormous practical difficulties in abolishing slavery in as peaceful a way as possible but he didn't live long enough to practically apply his ideas.

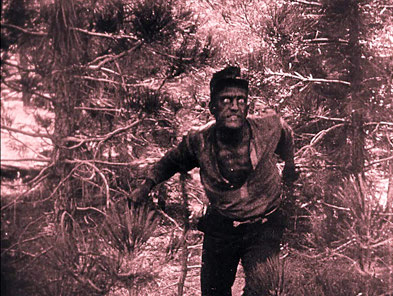

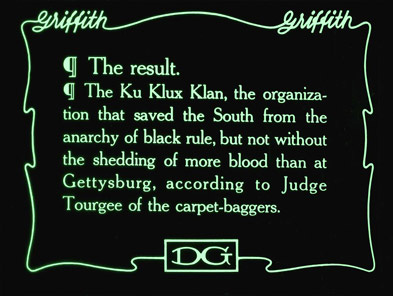

Then follows the 'Reconstruction' that, according to the movie (I claim to be a mere Wikistorian) meant a black majority rule and the passing of some knee-jerk, feckless, anti-white legislation. On this one topic, the Wikipedia entry is over 21,000 words long and its complexities are too much for me to go into here. Suffice to say, Birth Of A Nation doesn't deal in complexities. The movie presents the black rulers as ill educated, uncultured oafs (uh... Okaaaay) and sets up a white southern army leader and the rising star of the Cameron family as the man entrusted with the mission of routing the black majority from his beloved homeland. He was known as 'The Little General' or if you are a practicing psychoanalyst, D. W. Griffith's dad. While idly watching children play, the Little General observes white youngsters place sheets over their heads (your classic 'ghost' image). Black children approach but then run away, wide-eyed in fear (another sub-textural judgement of the black child as a credulous, superstitious idiot?) It's an 'Aha!' moment and the Ku Klux Clan is born. Hurrah! The irony's a little too heavy for this poor paragraph. Here is where things get ideologically stickier than asphalt in Death Valley. Gus, a black Freedman and ex-soldier approaches the younger Cameron daughter, Flora. He says he wants to marry her. She runs away, terrified. In some shots as he chases her, he is literally foaming at the mouth (demonize much, Mr. Griffith?) She reaches a cliff edge and rather than face her stalker, she plunges to her near death and eventual doom.

The 'heroic' clan arrives, dispenses justice (some justice) and leave Gus's corpse on the doorstep of Silas Lynch (Lynch? You have to be kidding). Lynch is the half-caste (or to use the nasty term, 'mulatto') friend of abolitionist, Mr. Stoneman. Well, from here on in it's the Ku Klux Clan riding to the rescue like demented horse-riding, bed sheets. Whenever they are on screen I cannot help thinking of Tarantino's Django Unchained's comic take on their masks (it's rumoured that famous director John Ford is one of the riders actually having trouble with his own mask in Nation) or what a student rag week version of the Grand National might look like. Remember, I have been raised and educated to see the Ku Klux Clan as nothing but frightened white men desperate to subjugate the black population to maintain their power base. Beyond that I can't process any other reading. From Mr. Griffith's point of view (he was a lot closer to the American Civil War than I will ever be) the Clan may have been heroic but... wait. I'll go into this a little further down under the sub-title Controversy. Suffice to say the movie ends happily ever after and anyone with any conscience will sit there mouth agape at the politics but with a definite and perhaps inevitable grudging respect for the enormous accomplishment of the movie itself. Technically on a scale of achievement, this was 1915's Apocalypse Now.

Talk about a reputation preceding the main event... Birth Of A Nation has been on my radar for a long time but for the usual and regrettable reasons, I never gave it time. I thought that it must be a product of its past and therefore fettered by its technology and impeded by its era's zeitgeist. Let's not even mention its hugely contentious political point of view. Of course, this is an absurd assumption for a film aficionado to make (however true it may turn out to be) but reviewing for this site always demands a more than surface level engagement and I've not been disappointed with the experience of delving a little deeper into a movie since I started writing for Outsider a decade ago. The punch line should be "That was until I saw Birth Of A Nation", but it simply isn't true. Seeing a film this steeped in film culture and history and taking a twenty-first century stab at appreciation is hugely rewarding. First of all, here are a few aspects that a curmudgeon or even a fan of modern film may put in the negative column of Nation appreciation... (let's leave the big issue until later).

Speed:

According to more than a few reports, director David Wark Griffith insisted his massive movie be under-cranked. I'm mystified as to why. Cameras used to be manually operated, 'cranked' in the silent era so there was never a uniform speed at which the film was exposed. If the film were under-cranked, projectors screening it at a 'normal' speed would make the action look speeded up. Maybe Griffith was aware how long his masterpiece was going to be and chose to tell more story in a shorter amount of time. Doctor Who's Steven Moffat should try it. It's the curse of a lot of silent cinema, seeing old movies at a 'normal speed' and feeling that it's aesthetically 'wrong'. But at well over three hours, Birth Of A Nation must have been a hearty shock to a turn of the century audience. Fed on silent shorts, viewers must have felt the cinematic equivalent of going from Puccini's La Bohème to Wagner's Ring Cycle in running-length terms. But it was a massive hit with a profit of over 450 times its budget. This is the equivalent of The Avengers (budgeted at 220 million dollars) making almost 100 billion back. It's fair to say that people went to the movies a lot in 1915. Those were the days.

Theatrical Roots:

So Birth Of A Nation nestles in a world in which everyone moves just that tad quicker than normal. It's also a very theatrical world in which if you die, you have to throw up both arms wildly to the sky as if releasing your dove-soul to heaven as quickly as possible. Unless you are Lillian Gish (swoon), you should emote as if on stage making sure those at the back can figure out if you're angry, upset, happy, nonplussed, shocked etc. Remember most movies in this era were filmed stage plays and it took someone like Griffith to re-imagine cinema as a separate art form free from the constraints of the proscenium arch, the frame surrounding a theatrical stage. This was a huge leap. Also there's a great deal of 'eye' acting going on and some of it out of historical context appears hysterically funny.

The unsettling casting of featured black parts with white actors blacked up (aka 'black-face') adds to the movie's racial controversy. Could this be compared to Greek theatre in which women's parts were played by men? Is there still that superiority bullshit going on? On the IMDB trivia page for the movie is this gem (jaw-droppage on 9.9)... "Some of the black characters are played by white actors with make-up, particularly those characters who were required to come in contact with a white actress." Jesus H. Christ on a tandem. It beggars belief. If it's true of course... And who the hell knows?

Film Craft:

On many occasions, mattes are employed to isolate a part of the screen, a sort of in-frame editing, masking a part of the frame in black to draw your eye to one specific part of the screen. It's fascinating that this technique predated the close up for emphasis. That said there are hardly any close ups in Nation. It's not as if the cameras, lenses and stock couldn't handle it. At 3 hours, 3 minutes and 59 seconds is a mid-shot of Gish and that is as close as it gets. But where Nation really gets it right is in its birth of the continuous action edit. Most cuts in the film are jump cuts, cuts that pay no heed to continuity and simply present the next shot as a matter of course but once in a while there is a cut that could have been made today and this still knocks my socks off. Remember that film was a nascent language and in 1915 we'd hardly passed the "Ga ga" and "Goo goo" stage. Out of seemingly nowhere, Griffith suddenly started to form real words. Russian director Sergei Eisenstein still takes a lot of credit for the evolution of film editing but his masterpiece, Battleship Potemkin, was still a decade away.

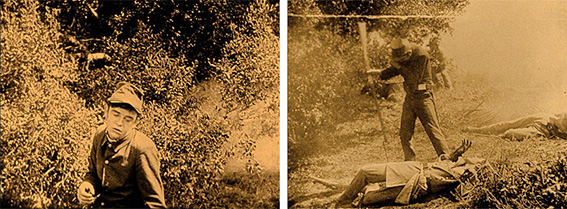

Here is what we would consider today a 'bad cut', the continuity completely disregarded because in 1915 there was no such thing as editorial continuity. The frame on the left is the last frame of the first shot and the frame on the right is the first frame of the following shot...

What's peculiar is that within the shots are points of action where a much smoother cut could have been made. The concept of editorial continuity must have been a passing thought. It astonishes me that the very next cut in the film would not be out of place in Quantum Of Solace. Not only is it an action cut that works, it also compresses the action to speed up the scene (see below).

This simply is sock knockage to the nth degree! What surprises me further is that Griffith himself was credited as the sole editor while busily executing two distinct creative methods. If there were another editor credited, I'd have understood the schizoid nature of the technique throughout the film. Given the director's monumental authorial ego it doesn't surprise me he was the only one credited but it was almost as if he was timidly testing the continuity waters and then falling back on the less demanding jump cut. Jump cutting then was de rigueur, the standard option like the western standard of writing left to right. Smooth, action oriented, continuity minded editing was the black sheep of the editorial family. Griffith hadn't given birth to a nation as much as he had created a cinematic language that we still speak very loudly today. This cannot be underestimated no matter how awful the racial politics are in the movie and how much they have besmirched his extraordinary achievement.

And then there's the accompanying music. The Mont Alto Motion Picture Orchestra gives no composition credit but despite the score being continuous (that's a lot of music) and a great deal is repeated, I found the score reassuring and 'right' for the film. It doesn't spot the events as closely or as effectively as later composers would be expected to do (spotting is the process of deciding which parts of the film need specific music) but then is this a score very much like one you may have heard performed live in 1915? In which case, it's ten out of ten for temporal cultural sensitivity.

The colour coding of the scenes is notable; each scene has a tint and sometimes the tint is changed shot for shot inside the same scene. I'm sure there is an emotional resonance intended (red for warfare etc.) but as I wasn't that motivated to find out the 'code' I just accepted it as part of Griffith's plan (though can I be sure the colour coding was in place at the time of exhibition?)

There's not a great deal I can add on the film without diving into the controversy issue, so let's get stuck in.

There is a trap I'm trying very hard not to fall into. It is the 'that was then, this is now' trap. It is almost child's play to rip gore-gout gashes out of Birth Of A Nation from today's perspective. And it may even be fun to write and diverting to read but... Respect is due however much this extraordinary work has been slighted by its own portrayal of American history, hoist by its own petard, if you will. I've pointed out what may be alien to a modern audience and referenced a checklist of silent cinema tropes which seem horribly quaint to us today but I want to stay on the side of reverence and if that means this review 'feels' like its condoning the Ku Klux Clan as a force for moral rectitude, then that's a reading way off the mark and nowhere near my intention. I will deal with this contentious side of the story but will try hard not to erode the filmmaker's achievement after what seems like an unforgiveable lapse in political judgment.

OK. If you love cinema, it's polite, at the very least, to acknowledge its birth, its infancy and perhaps even its hormonal rant. There is such an abyss-wide chasm between what cinema was a century ago and what it now is, it's almost surreal. If today's cinema is an iPod (let's keep this mainstream despite the welcome bias of this site), yesterday's is a tramp with a harmonica, a tramp who moves jerkily not only in black and white but a shade too swiftly for our comfort. The extraordinary thing is that yesterday's cinema is also a supremely talented tramp with a finely tuned harmonica whose skill and virtuosity moves you if not to tears then to an appreciation that the human animal is a constant in the creation of art regardless of the tech.

David Wark Griffith had a hand cranked movie camera and the participation of thousands of people. Joss Whedon had cutting edge CG (and a Hulk) as well as thousands of people behind the scenes. Both are artists. Both expressed their take on the world. One of them is a geek god and the other was a man who looked at the world and said "What?!!!" after the world complained about his political views. He made a film in which the heroes are the brave (ha!) anonymous, bed-sheeted horsemen who quelled the black uprising at the end of the American Civil War. Yes, it's the Ku Klux Clan, the mask-wearing schmucks led by Don Johnson in Tarantino's Django Unchained. I'm not sure how I feel about a whole movie-going generation being introduced to one of the most heinous groups in world history by essentially a blood spattered comedy but no one reads books now, is that right? The masks may have been comically referenced in Tarantino's movie but there is nothing funny about a large and frighteningly well-represented group of terrified men who feel the need to anonymously dispense vigilante justice against a different colour of human beings. I have to admit my introduction to the KKC was via another classic comedy western. I have Mel Brook's wonderful Blazing Saddles to thank for that. "Daddy love Froggy. Froggy love Daddy?"

Griffith may have been unrepentant at the time but he made his next movie (Intolerance) mostly inspired by the reaction to Nation. To him, the Civil War was recent history. To us, the idea of the Ku Klux Clan is abhorrent and wildly out of whack with where human culture now resides. So do we think less of this extraordinary film because of that reading, that harsh but essentially correct judgement from history? Like most questions in life, the truth is a blurring shuffle of "Yes!" and "No!" and twenty thousand acres of 'in between'.

Cast your own vote.

Presented in the original 1.37:1 aspect ratio, this is a 1080p version mastered from the surviving and surprisingly spry archival 35mm elements. The title cards seem to be cleaner than the actual movie or perhaps tweaked so that the words are very much clearer. They have an almost neon feel about them, very photochemical. Some cards are not on screen for very long at all which suggests any surviving negative and prints are less than fully intact. The actual film is (how to say this without giving offence to the restorers?) justifiably dirty with negative scratches and dust spots aplenty. Misaligned cement joins are often apparent. It has not scrubbed up as well as other silent classics probably due to the age of the film stock. Grain is very apparent in the 1080p format, much more so than any other silent film I've reviewed. The colouring of the different scenes either dials down or up the extent of the damage but as far as robbing the story of any power goes, the damage is inconsequential. Some of the 'special effects' are decidedly primitive (double exposures and 'freeze frame-cut-resume action' effects) but you have to take into account what audiences were used to a hundred years ago. Eighteen years later in 1933, people believed a giant ape was terrorizing New York. Context is all. Summing up, the picture quality is no more or less than I expected it to be but it's still a treat to have it in the best quality it can be. I can't imagine a 4K disc (coming soon in 2015) prising any more from the original material.

The only sound, the music by the Mont Alto Motion Picture Orchestra, is presented in 2.0 stereo and DTS–HD Master Audio 5.1. Given a choice, I'd go for the 5.1 but after numerous comparisons, I can't say the subtle presence of the score in the rear speakers and not too much generated by the sub-woofer makes a huge amount of difference from the straight stereo. Do I have to say there are no sub-titles for a silent movie with inter-titles? No, didn't think so.

There seems to be a few odd discrepancies between what's listed on the disc in the press release and what's actually on the physical disc. I'll comment on these omissions and additions as I come to them.

Short archival introductions to the 1930 re-release of the film by D. W. Griffith and Walter Huston (7' 45")

With some of the most appalling acting I've ever seen in a good long while, three young children eavesdrop on actor Walter Houston interviewing D. W. Griffith as an introduction to the re-release of the movie in 1930. And it's a doozy. Huston's first statement is "Is it generally known that you're a southerner?" Nice! We establish that Griffith's father was a fighter on the southern side. "The Clan at that time was needed and served a purpose." Says Griffith. Oh boy, but then I wasn't there. He gets Huston to read President Woodrow Wilson's account of the Reconstruction and the need for the Clan to claim order. Griffith concedes that this is a very unusual thing but it still leaves a sour taste of 'truth' as seen from one particular point of view. Griffith comes over a little pompously and Huston doesn't give him an easy ride but there is a feeling that this introduction was needed because of the outrage generated by the movie when it was first released.

Newly re-discovered original Intermission Sequence and 1930 re-release title sequence (1' 10")

Despite the wording on the press release, I could find only the latter of the two listed above. It's simply the freshly minted title cards for the re-release of the movie in 1930. No surprise that Griffith finds room on the cards to loudly blow his own confederate trumpet. Again.

The Making of Birth Of A Nation – 1993 (24' 00")

And this Extra is not listed at all in the Press Release. Curious. It's probably due to a duplication of the American release press materials. No matter. It's a terrific Extra Feature. The author of the original novel 'The Clansman', upon which the movie was based, is described as a white supremacist (should we be surprised? Why is that term 'supremacist' never good news?). The use of the Clan in the movie spurred other filmmakers to do the same; one film was produced by a white Mormon company and another, a satire, financed and acted by blacks (real ones this time). I was starting to think Griffith's detractors were a little too silent for comfort. State wide officialdom recognized that movies were a business capable of representing so called real events but were wary of the power they held to sway public opinion. Nice to see that argument was raging even then. World War II now seems to be a memory enhanced by Steven Spielberg. Not sure how I feel about that either. I'm not even sure that a cold book of facts is any less injurious to the 'truth'. I guess you just have to have been there. This is a solid Extra if only for the context it reveals at the time the movie was made and the revelation of the tricks of Griffith's trade.

Seven Civil War shorts directed by Griffith (1 hour 49' 07")

In the Border States (1910); The House with Closed Shutters (1910); The Fugitive (1910); His Trust (1910); His Trust Fulfilled (1910); Swords and Hearts (1911); and The Battle (1911)

These are all, in some senses, Birth Of A Nation's first baby steps. You can see Griffith growing in ambition as a director via these shorts but they are not easy to watch by any means. And I'm not talking about the various levels of physical damage each short displays (the last one, The Battle, looks like it's come off several generations down the line) or the overuse of the familiar marching tunes of the Civil War endlessly played on an old upright piano. If we ignore the same archaic techniques that impair the main feature (from a modern perspective), we are still left with lots of 'black-face' acting and that's just too painful to watch. Even the children are white kids in 'black-face'. Jesus.

Each short has a very strong moral grounding but watching them en masse gives you a curious and uncomfortable feeling. The presentation of each film presupposes an unspoken assumption about the world the shorts collectively depict. That world is one in which whites rule by default, blacks are secondary and prone to panic in any dangerous situation. It is reductionism at its most tasteless level, something conceivably 'normal' in 1910. I can't imagine what viewers thought as they left the theatres. Let's just say that Griffith was not raising awareness of racial equality. I can't recommend viewing the shorts unless you have been obliged to review them. I shudder at the world they sprang from.

A Booklet with writing about the film, rare archival imagery, and more.

As I've said many times before, these booklets are often a physical highlight of the release. I also find the disclaiming language hilarious. How's this:

"In the articles which open this booklet, D. W. Griffith and Thomas

Dixon express attitudes towards race, and use descriptions of African-Americans, which sit outside of the prevailing attitudes of today, and which may well offend the contemporary reader."

Classic! "sit outside..." They are borderline Rodney Kingisms.

Here's the content of the Booklet and a brief summation of the individual articles:

On THE BIRTH OF A NATION by D. W. Griffith / 1916

Jeez. This is not comfortable reading. Griffith's story of how a former slave is threatened as a joke by his father is utterly and unforgivably abhorrent. Read it and celebrate the progress we have made.

A Nation Is Born

by Thomas Dixon / 1915

As soon as you read the phrase "the problem of the negro..." you're not exactly on Dixon's side, are you?

Brotherly Love

by Francis Hackett / 1915

This is a rebuke of Dixon's worldview (thank God) and the arguments are sound and in the best sense of the word (if it can ever have a best sense) 'righteous'.

Capitalising Race Hatred

New York Globe editorial and D. W. Griffith response / 1915

Griffith defends himself against accusations of racism by pushing the art and craft of the motion picture. It's nowhere near enough to absolve him.

The Birth of Film as Art by Seymour Stern / 1945

A few short paragraphs on what Griffith may have wrought in the service of cinematic art.

A Guilty Pleasure

by Michael Powell / 1981

Ah, Michael Powell. One of the greats so no wonder he uses the phrase 'guilty pleasure'. He is rightly in awe of its greatness while side-stepping over all the race ruckus.

Facts About THE BIRTH OF A NATION 1915

This lists some interesting snippets of utterly irrelevant information (each artillery shell cost $80!) but fun for a passing cineaste's eye.

The Booklet ends with the notes on viewing the film correctly and the Blu-ray credits.

Birth Of A Nation, as the press release says, is "...a great and terrible masterpiece." You won't get much argument from me. I cannot recommend the film as a stand-alone 'must see' movie because it really is too dated and too objectionable in many aspects but as a record of the birth of cinema, it's a must-have. Any die-hard cinema aficionado needs this one on their shelves (the cinematic equivalent of baby pictures on a family's mantelpiece) and so another bravo to Masters Of Cinema for making this birth available to all.

|