"Slow films in which everyone is galloping and gesticulating; swift

films in which people hardly stir . . . not beautiful photography,

not beautiful images, but necessary images and photography." |

Robert Bresson, from Notes on the Cinematographer, 1975 |

"In the case under scrutiny, the pedagogical approach of the blind woman at the far

end of the ward seems to have had a decisive influence, that woman married to

the ophthalmologist, who never tired of telling us, If we cannot live like human

beings, at least let us do everything in our power not to live entirely like animals." |

José Saramago, from Blindness, 1997 |

In the July issue of Sight & Sound, Nick James wonders why such an unprecedented number of films competing for the Palm d'or at Cannes this year were about death and grieving. It may, he says, be mere coincidence, it may be that a high proportion of industry movers and shakers have "reached the age when grief weighs heaviest," or it may reflect a subconscious collective mourning for cinema. After noting that the New York Times has ceased to guarantee distributors it will review every film screened in its city each week ("because of the increasing volume of films released each year"), James concludes that "cinema's special status among the moving image arts" may be atrophying. He is quick to point out, though, that the seventh art has proved far more durable than Susan Sontag suggested in her famous New York Times essay of 1996, 'The Decay of Cinema'. In that essay, Sontag lambasts the flood of formulaic, "astonishingly witless" films "made purely for entertainment (that is, commercial) purposes." "The sheer ubiquity of moving images," she says, "has steadily undermined the standards people once had both for cinema as art at its most serious and for cinema as popular entertainment." Then as now, more is less.

Joshua Oppenheimer's companion films The Act of Killing (2013) and The Look of Silence (a film about death and grieving if ever there was one) prove that cinema is alive, kicking, and as capable as ever of responding with artful seriousness to the deepest, darkest, most difficult questions facing humankind. Perhaps the glut of Cannes competition films about death and grieving reflect the plethora of horrors the 20th Century left behind for us to process. Nobody has done more than Oppenheimer to highlight one of those horrors, by breaking the deathly silence surrounding the Indonesian genocide of 1965-66. In the collaborative campaign film The Globalisation Tapes (2003), in The Act of Killing, in The Look of Silence, in countless interviews, at every opportunity he has raised awareness of historic atrocities that had been swept under the carpet both in Indonesia and the West. In doing so, he has generated an essential examination of the massacres and the part Western governments played in them. It is a significant achievement that testifies to the power of cinema and, particularly, documentary. Kafka said: "We need books that affect us like a disaster, that grieve us deeply, like the death of someone we loved more than ourselves . . . A book must be the axe for the frozen sea within us." We need films that affect us that way too. For all its spectacular theatrical excesses, The Act of Killing was such a film. Although less flashy, indeed admirably and elegantly restrained, The Look of Silence is one too.

For both the Act of Killing and The Look of Silence, Oppenheimer persuaded some of the death squad paramilitaries responsible for the Indonesian mass killing of 1965-66 to reenact their crimes for the camera. If he received too little credit for his crafty knack of insinuating himself into the good graces of those murderers, the 40-year old Harvard-educated American otherwise deserves all the acclaim and awards that have been heaped upon him. The much-merited rewards The Act of Killing reaped, though, came at a cost. More than any film of recent years, it graphically demonstrates a few problems bedevilling modern film journalism: copycat reviewing, PR and marketing spin, and the tendencies of reviewers to uncritically regurgitate directors' comments. The perennial problem of copycat reviewing was compounded by the slight of hand of the film's marketeers, who made free use of gushing quotes from Werner Herzog and Errol Morris (executive producers of the film) to promote it. The film was also ill-served by the thunderous applause of the herd of independent minds, which effectively drowned out dissenting views and operated to the detriment of rigorous criticism of the film.

Oppenheimer is, in a sense, a victim of his own success, his keen intelligence, and his fertile imagination. It isn't, of course, his fault that the film was presented that way or that the hyperbolic reaction to the film circumscribed considered criticism of it, but his eloquence is such that he dictated the terms on which the film was received. Put more bluntly, his consummate skill at foreseeing and forestalling criticisms of his work delimited the reach and range of the debate surrounding it. Similarly, his artful invention got in the way of his subject. Discussing The Act of Killing in the Guardian,* Nick Fraser, editor of the BBC's Storyville series, says: "Documentaries can be undone by too much ambition. Too much ingenious construction and they cease to represent the world, becoming reflected images of their own excessively stated pretentions." To put it another way, reality, as Philip K. Dick noted, doesn't go away when you stop believing in it. In taking the bold but rash decision to emphasize the imaginative and performative at the expense of the factual and political, Oppenheimer set dangerous precedents that beg urgent questions.

He says he aimed to create "a documentary of the imagination" that worked "not as a window on Indonesia, but as a mirror for us all." Might this nominal emphasis on the universal over the local, and that blurring of narrative and non-fiction strategies, not have left Western audiences with a blurred, vague sense that 'evil things' once happened 'over there' to unfortunate brown others, rather than improved, precise insight into the specific circumstances of a particular atrocity and actual country? And might Oppenheimer's decision to bleach his subject of politics not play into the very hands of those he says he set out to expose? Those two questions echo in the two overriding concerns expressed by those few critics who broke ranks to actually criticise The Act of Killing: that it foregrounds the génocidairesat the expense of their victims and that it failed to provide adequate context for the genocide. The Look of Silence, focusing as it does on a single victim of the massacres and one grieving family, might have been made to answer the first of those criticisms but, sadly, it duplicates the contextual lacunae of the earlier companion film. Partly to counterbalance that shortfall, partly in response to the extraordinary amount of attention accorded these films, I will earth this review of The Look of Silence in a few thoughts on the complex contexts of the film's reception and that of the massacres themselves. I'll begin with few pertinent words about Susan Sontag.

In the 'Decay of Cinema' (first published, as 'A Century of Cinema,' in Frankfurter Runschau a year earlier), Susan Sontag linked what she saw as cinema's "ignominious, irreversible decline" to the decline of the intense, almost religious rituals of cinema-going and love of cinema as all-consuming passion: "Cinephilia has no role in the era of hyperindustrial films . . . If cinephilia is dead, then movies are dead." She was wrong and would, surely, have been bucked by the new forms of cinephilia facilitated by new technologies, expressed in online analysis and discussion of film, and glowing on computers and television screens in homes around the world. The hope expressed by Bryant Frazer in Senses of Cinema that "the internet may deliver a second century of cinephiles from video-bound solitude" has come to pass. Sontag may, though it pains me to say so, have been right about the expiry of the era of the magical darkened room and the shared social experience. Digitization, social fragmentation, increased suspicion of others, and changes in film exhibition have certainly hastened the fragmentation of the audience for films, with serious consequences for documentary film culture and films like Oppenheimer's.

As Nick James says in his July Sight & Sound editorial, arthouse exhibitors have responded to a flood of films that mean smaller profits for all involved by raising ticket prices. James returns to that same theme his August editorial. Discussing the recent boom in new and renovated cinemas in London, he say: "Such a display of confidence in cinema as a collective 'night out' experience, such an investment of belief and bricks in its continuance as a competitive attraction, is heartening to an industry experiencing its own fragmentation – of platforms, of distribution methods, of experimental models . . . these cinemas have mostly gone for the high-tech, high-comfort, high-price experience." At a time many are struggling financially due to the fallout from the latest crisis of capitalism and from government austerity measures, this drives the final nail in the coffin of cinema as the most popular of the arts.

I recalled Sontag's pessimistic diagnosis about cinema's decline with a shudder recently after watching Nancy Kates' wonderful documentary Regarding Susan Sontag at Greenwich Picturehouse, with only half a dozen others, and again, a few days later as I watched Thomas Cailley's delightful debut feature Les combattants at the new Curzon Bloomsbury with just three others. Most recently, I thought of it when I returned to Greenwich to jog my memory about The Look of Silence (acting on Jonathan Rosenbaum's injunction that critics should always, where possible, see films twice; the first viewing being merely a means of erasing initial preconceptions). My preconceptions about Joshua Oppenheimer took a hammering, but that was the least of the surprises that awaited me in Greenwich. Having bought my ticket, I found my entrance to the cinema barred by a rope suspended between two chrome poles. Assuming a mistake had been made, I returned to the reception desk and was told I was the only one to have bought a ticket for the film. After consulting the projectionist, the manager 'kindly' agreed to screen The Look of Silence anyway, for me and me alone.

The idea that exorbitant ticket prices make cinema-going a luxury many can't afford is just one depressing aspect of those disconcerting experiences. In Regarding Susan Sontag, Kates details Sontag's pained response to the publication of her celebrated essay 'On Photography': distraught at the idea she wasn't good enough by her own exacting standards she complains to her friend Don Levine, "It's not as good as Benjamin, is it?" Sontag once said, "death is the opposite of everything"; for her, death was the opposite of getting better, in more ways than one. Richard Brody says: "Her writing was the synecdoche of her very self." Her literary legacy, her pitch for immortality, was almost as important to her as life itself. This may be what her son, David Rieff, is driving at when he says, "She was afraid of extinction."

Before her cinephile ardour cooled, Sontag wrote, in 'Against Interpretation' (1966), that, "cinema is the most alive, the most exciting, the most important of all art forms right now." Any decline in the audience for cinema is, ironically, a decline in interest in her and her writings on cinema. Discussing questions of taste and reception, Jorge Luis Borges observes: "The taste of the apple is neither in the apple, which cannot taste itself, nor in the mouth of the eater. It requires a contact between them." Which is to say, books and films scarcely exist without reader and viewer, without an alert and responsive readership or audience. If a film has no audience, it is dead. If a film about Susan Sontag has no audience, it is dead and she is doubly dead.

Much the same might be said about the victims of the Indonesian massacres who are a present absence in The Act of Killing and, finally, thankfully, present in The Look of Silence. Fortunately, Sontag lives on in her novels, her films, but most particularly in essays like 'Regarding the Pain of Others'. She also lives on, doubly so, in her son, David Rieff. who made a significant contribution to immortalizing her by editing a three-volume collection of her Journals & Notebooks. In the second volume, As Consciousness Is Harnessed to Flesh (1964-1980), he includes a list, compiled in 1977, of her Top 50 films** – to which he adds an intensely frustrating footnote: "The list continues up to number 228, where SS abandons it." We see enough to know that she favoured narrative over documentary cinema. Or do we? She made documentaries herself, after all, and although they don't loom large in her long lists, there are clues she was thinking about the form when she stopped writing on cinema. In 'Goodye Susan, Goodbye: Sontag and Movies' (an essay first published online Synoptique and republished in Goodbye Cinema, Hello Cinephilia), Jonathan Rosenbaum recalls attempting to commission Sontag to update her essay on Bresson by now considering Au hazard Balthazar and Mouchette. Sadly, Sontag declined the offer. Her cinephilia had faded. As Rosenbaum says, " . . . she wasn't too keen to write more about film anyway. And if she were, I asked, who would she want to write about? Vertov, she said, without a moment's hesitation."

Sontag's coolness about documentary is as disappointing at the cooling of her cinephilia. She was a public intellectual who never shied from unpleasant facts. If she didn't appreciate the importance of documentaries, it bodes ill for others. It bodes ill, too, that I sat in an empty cinema to watch The Look of Silence. That anecdotal evidence might reveal nothing more significant than that cinemas occasionally have one-off quiet screenings. Even if that's so, and I hope it is, the problem of increased admission prices and smaller, more affluent audiences for films remains. That alone has serious implications for documentary film culture, public conversation, and for democracy itself. People can and do, of course, watch films by many other means, but there is something unique and uniquely charged about the way we react to films and what they show us in cinemas. At one with an audience we feel more deeply, alone together in the dark of the cinema we focus more clearly, in a setting largely devoid of distractions we concentrate more intensely. And when we go to the cinemas with others, the sharing of reactions, reflections and knowledge after screenings can be as important as the films themselves in unblocking congealed thinking and chipping away at the frozen sea within us.

People can and do, too, read books on subjects such as the Indonesian genocide and, say, that perpetrated by the Khymer Rouge. Sadly, they did not, generally, respond to Peter Weir's The Year of Living Dangerously (1983) by rushing to buy books by Christopher Koch or John Pilger any more than they reacted to Roland Joffé's The Killing Fields (1984) by immediately reaching for Philip Strong or John Pilger. There is no pattern to the way we move from films to books and vice versa. The way we respond to urgent new information, and the reasons we elect to build on that information, are subject to even more mysterious combinations of circumstances and character; to the vagaries of accessibility, convenience, energy levels, marketing, mood, timing, free time, and so on. We can say, though, that we are more likely to watch films if they are readily available and widely discussed. Audiences might be more inclined to search out Robert Lemelson's 40 Years of Silence: An Indonesian Tragedy (2009) and Maj Wechselman's The Women and The Generals (2010) after seeing Oppenheimer's films or Thet Sambath's Enemies of the People (2010) and Rithy Panh's S-21: The Khymer Rouge Killing Machine (2003) after seeing Weir's – if those films come to their attention, at curated seasons in independent cinemas, for example.

I mention the contexts of the film's reception partly to unburden myself of my fear that almost empty cinemas – or, perish the thought, a future without cinemas – would mean a colder, less sociable world and a further diminution both of our concentration spans and of our capacity to feel intensely. In 'Necessary Conversations', the concluding chapter of her book Alone Together: Why We Expect More from Technology and Less from Each Other, Sherry Turkle uses Ridley Scott's Blade Runner to make a point about the way new technologies are affecting us. Three months before his death in 1982, Philip K. Dick watched footage of Scott's adaptation of his novel Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?. He described it as "The greatest 20 minutes I've ever experienced . . . a tremendously information-rich experience . . . like being transported to the ultimate city of the future."

In Alone Together, Turkle suggests that the dystopian future envisaged by Philip K. Dick and Ridley Scott may be closer then we'd care to believe. She says: "I have argued that knowledge of mortality and an experience of the life cycle are what makes us uniquely human. [Blade Runner] asks whether the simulation of these things will suffice . . . Decades after the film's release, we are still nowhere near developing its androids. But to me, the message of Blade Runner speaks to our current circumstances . . . We have entered a realm in which conventional wisdom, always inadequate, is dangerously inadequate. That it has become so commonplace reveals our willingness to take the performance of emotion as emotion enough."

Fiction films like Blade Runner and riveting documentaries like Oppenheimer's (and the experience of watching and discussing them with others) generate necessary conversations and challenge conventional wisdom. Like the BBC's Nick Fraser, though, I'm not convinced that by persuading mass murderers to reenact their crimes and reminding us that performance is a ubiquitous factor in our interactions, Oppenheimer tells us anything new about the human condition. After making The Act of Killing, he must be more aware than most of the problem of feigned emotion and phoney performance. He should also be acutely aware of the crying need for rigorously inquisitive, fearlessly inquisitorial documentaries that cross-examine power more robustly than the mainstream media does.

In an interview with Nick Bradshaw in this month's Sight & Sound, he says: "Campaign films say, 'This is a lie' but they won't show its workings, and that's bound to have less impact than deconstructing the lie itself'. Not so. Case in point: I recently reviewed Amir Amirani's We Are Many; it is a slightly artless campaign film that shows the big lie used to justify war in Iraq, and unravels its workings. In Amirani's documentary, former New York Times staffer Patrick Tyler (a journalist who learned his craft working for none other than Bob Woodward on the Washington Post), says of the 'dodgy dossier' on weapons of mass destruction: "There was a grand deception in which we all share various amounts of responsibility. Everybody didn't do their job . . . The military-industrial complex has its analogue in the press, the media-industrial complex." Thanks the stars he was able to set the record straight in a documentary.

In an interview for New Statesman magazine, though, Oppenheimer says: "I think one of the problems is that genuine investigative journalism has been so eviscerated, so underfunded, that non-fiction filmmakers volunteer to fill in that space. And that's one of the biggest threats to non-fiction cinema as an art. Some of our greatest talents are making great works that are fundamentally what journalism should be doing." I see that not as a 'threat' to documentary film culture but, rather, as the fulfillment of its duty. In The Four Quartets, arch-conservative genius T.S. Eliot said, "human kind/Cannot bear very much reality." It can, does, and has no choice but to do so. In an age of disinformation, when the mainstream media increasingly operates as a propaganda machine for power, we need documentaries to furnish us with facts and information that are not, and have not been, provided elsewhere. Tarkovsky believed that, "In cinema it is not necessary to explain but to act upon the viewer's feelings, and the emotion which is awoken is what provokes thought." In documentary, explanation provokes thought which then awakens feeling.

It is a depressingly familiar story, particularly to the peoples of Africa, South East Asia, and Latin America. A military junta seizes power with the covert support of Western powers. All effective opposition is brutally crushed. An opportunist army commander establishes autocratic rule. Anti-communist rhetoric is deployed to cow and control the population. Freedom of association and assembly, of speech and of the press are curtailed. Corruption, nepotism, and state-sponsored violence soar. Civil society eventually regroups and responds. The despot's son is jailed, his brother is jailed, but he himself is declared unfit for trial and evades justice.

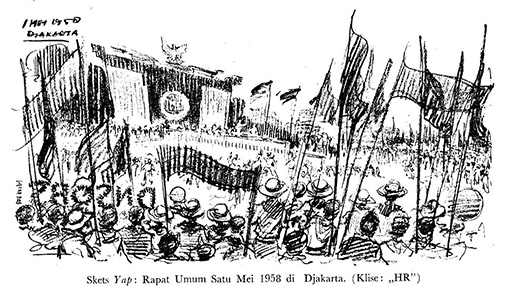

The thirty-three year rule of Indonesian dictator General Suharto follows that pattern precisely; it is a case study in developmental authoritarianism and brute Cold War power politics. When Suharto seized power in 1965, the Indonesian Communist Party (the PKI) had over three million members and could count on the support of millions more in grass-roots peasant organisations, trade unions, youth and women's groups. Unlike the Indonesian military and the CIA (which provided them with 'logistical support' and 'shooting lists' of left-wing, often non-communist activists), the PKI was committed to peaceful democratic change and due process.

About a million people were murdered during the 'anti-communist' massacres and anti-Chinese pogroms that accompanied Suharto's coup d'état. The CIA called the events of 1965-1966, "one of the worst mass murders of the 20th Century." William Colby, the CIA's director for the Far East at the time, compared the agencies' operations in Indonesia to the infamous Phoenix programme to 'neutralise' the Vietcong. Former State Department intelligence expert Howard Federspiel said: "Nobody cared as long as it was Communists that were being butchered." Far from caring, cold warriors in the overdeveloped nations celebrated the slaughter.

In June 1966, the New York Times called it "A Gleam of Light in Asia." In July 1966, Time magazine called it "The West's best news for years in Asia." Australian Prime Minister Harold Holt told the New York Times: "With 500,000 to one million Communist sympathizers knocked off, I think it is safe to assume a reorientation has taken place." After that 'reorientation', corruption, collusion and nepotism (korupsi, kolusi dan nepotisme) became so endemic in Indonesia that they were commonly referred to by the chilling acronym 'KKN'. Suharto's brutal 'New Order' finally collapsed in 1998 but, as Joshua Oppenheimer's elegantly restrained new documentary The Look of Silence shows, its toxic legacy still haunts Indonesia.

The film begins with a TV news report shot in the aftermath of the coup. We see NBC footage of once-organised survivors of the genocide at work for a Goodyear factory in Sumatra. The commentary informs us they "still work the rubber, but this time as prisoners and at gunpoint." It is a telling metaphor for the shift in the balance of power in Indonesian society, the fear and oppression that continue to disfigure it half a century later, and the amoral rapacity of unfettered capitalism. As Oppenheimer says in an interview for Cineaste (Vol. XL, No. 3): "The biggest tire company in the world was using slaves to harvest the rubber, getting the slaves from political prisons where prisoners were either starved to death or dispatched to local death squads to be killed. Essentially, American corporations, a mere twenty years after the end of World War Two, were doing what German corporations did in Auschwitz. He adds: "I had the feeling that I'd wandered into Germany forty years after the Holocaust only to find the Nazis in power. It was at that point that I knew I would take as many years as necessary to address this situation."

When I interviewed Oppenheimer a couple of years ago, at the Open City Docs Festival, I asked him how his Jewish origins affected his view of the genocide and his feelings toward the survivors of the genocide. He said: "I grew up with the notion that the aim of all culture, morality and politics is to prevent that kind of thing ever happening again. Unfortunately the phrase 'Never Again' has been tragically taken to mean this should never happen again to us. I heard perpetrators in Indonesia saying: 'If you want this to happen, then keep digging'. I understood that it was my moral responsibility to intervene, because here was a risk of history repeating itself." To repeat myself, I asked him, in the summer of 2013, why he hadn't filmed victims as well as killers. He said he hadn't felt able to, for fear of endangering his crew and his subjects. At a Q&A half an hour before we spoke, he'd gone further. He'd said: "The moment you bring survivors into the film, the viewer disengages." Er . . .

It transpires that Oppenheimer had already filmed the footage for The Look of Silence when he said that. When we met, I found him articulate and occasionally asinine, intelligent and insecure, sincere and disingenuous. It matters not a jot what I thought of him; it's the work, his talent and how he applies it, and the change his films help achieve, that counts. Besides, the best of us are a mass of contradictions. Contradiction betrays doubt. It is the uncritical and deadly certain who torture under orders. Documentary itself is riddled with paradox and perhaps the ultimate, most apt paradox of Oppenheimer is that he makes documentaries but says: I don't see myself as a documentary-maker because I hope to be documenting the human imagination and the way we see ourselves."

| What Do You Want? Information! |

|

Sadly, that NBC clip is the only archive footage Oppenheimer used in his intervention into history. Both his recent documentaries seem to me to let the perpetrators of mass murder and Western governments off lightly. Had he used more archive material he might better have made the case about Western complicity in the genocide that he's reiterated in interviews. That may be unfair; it may be that very little footage is stored in the vaults. Searching the internet for images of the massacres to accompany this piece, I was staggered by how few are available. It suggests a failure of journalism and/or a news embargo. The censorship and self-censorship surrounding Indonesia certainly didn't begin and end in Indonesia in the mid-sixties: when Oppenheimer raised the question of Britain's role in the genocide while accepting a BAFTA award for The Act of Killing, the BBC deleted his comments from the subsequent broadcast.

All of which makes it more, not less important that audiences get hard facts from documentaries. Given that the massacres of 1965-66 were partly perpetrated by Jihadists who felt threatened by land reform and the diminution of their influence due to democratic left-wing politics, and given that Indonesia is the most populist Muslim country in the world, that alone, for example, might have been useful information to deliver with a view to informing current debates about the origins and modus operandi of Islamic fascism.

The Look of Silence revolves around the singular figure of Adi Rukun, an unassuming optician whose elder brother, Ramli, was among those butchered during the genocide and who courageously confronts those guilty of his murder. The circumstances of his brother's death are detailed in a lower third commentary audiences are unlikely to forget. In early 1966, as the slaughter continued unabated, Ramli was cornered in a field by a death squad and stabbed until his insides spilled into his hands. Despite his horrific injuries, he somehow managed to escape and crawled back to his village. No sooner had he reached the family home, than he was picked up again by two local paramilitaries, Amir Hasan and Inong. They promised Ramli's mother they would escort her son to hospital for treatment but, instead, they bound his hands, threw him into a van with other 'subversives', and drove him to a now-infamous site of carnage at nearby Snake River. There, they stripped Ramli naked and hacked at him with machetes. Mocking his cries for mercy, they then sliced off his genitals and rolled his mutilated corpse into the river.

Ramli's Rukun's murder, symbolic of hundreds of thousands more, took place near the city of Medan in Northern Sumatra. I foregrounded my review of Oppenheimer's feted companion piece, The Act of Killing, with a 1965 report from Time magazine that brings the grim reality of those events into sharp focus. It seems to me to bear repeating: "The killings have been on such a scale that the disposal of the corpses has created a serious sanitation problem in East Java and Northern Sumatra, where the humid air bears a reek of decaying flesh. Travellers from those areas tell of small rivers and streams that have been literally clogged with bodies; river transportation has at places been seriously impeded"

Imagine, if you will, the Danube or the Rhine, the Thames or the Seine, the Hudson or the Mississipi awash with corpses. When catastrophes on the scale that befell Indonesia have happened in the overdeveloped world, they have not been swept under the carpet, as the Indonesian mass killings have been, and literally. As Stefan Simanowitz says in New Internationalist magazine***: "Mass graves and mass tourism are not happy bedfellows . . . With its heavy reliance on the tourist industry it is understandable that many Balinese are reluctant to discuss the events of 1965." Simanowitz quotes an anonymous campaigner, who says: "I have spoken to developers who frequently come across bodies when digging foundations for tourist hotels in Kuta and Sanur . . . They instruct the builders to ignore the skeletons and to keep on building." Building on corpses, voila, another metaphor for capitalism.

As the closing credits of The Look of Silence chillingly reveal, anonymity is a prerequisite of survival in Indonesia. Dozens of those involved in the making of the film could not be named due to the intimidating atmosphere of enforced silence that pervades Indonesia. We see Adi's son being indoctrinated with the anti-communist state line, as successive generations have been since 1965. We sense the fear in society. This makes Adi Rukun's courage, determination, and dignified humanity all the more admirable. A softly spoken, gentle man, he may now be the world's most famous optometrist. It is cause for concern that he will also, therefore, be well known to an infamous authoritarian state with a disgraceful track record of murdering its critics. We are, fortunately, assured that he is in safe hands. Adi is the star of the film, which couldn't have been made without him. His profession enables him to tentatively question those who killed the brother he never knew about their role in the darkest period in his country's and his family's history. That he interrogates men who boast about drinking the ("salty and sweet") blood of their victims with a quiet, patient dignity disarms them (and us). Time and time again, his interviewees reach a point of embarrassed discomfort, before falling back on threats of violence.

As he tests their eyesight and adjusts various lenses, Adi has time to press and probe and then, as is often necessary, beat a diplomatic retreat. These were killers then and remain dangerous now. Time and again the final, brutish message he receives is: 'Shut the fuck up, or else!' M.Y. Basrun, a long-standing, if not upstanding member of the regional legistlature, typifies the tone of many of Adi's encounters when he says: "Do the victims' families want the killings to happen again? Then change! If you keep making an issue of the past – it will definitely happen again." Otherwise, the interviewees, like the 'actors' in The Act of Killing, evoke the epigram from Henry James's preface to Lady Barbarina (with which James Baldwin opens Another Country): "They strike one, above all, as giving no account of themselves in any terms already consecrated by human use; to this inarticulate state they probably form, collectively, the most unprecedented of monuments; abysmal the mystery of what they think, what they feel, what they want, and what they suppose themselves to be saying."

If Adi's parents' frail minds and bodies act as symbols of the atrittional damage done by a brutal dictarorship, the lenses through which Adi's monumentally short-sighted interlocutors stare back at him (and us) serve a symbolic as well as practical function. The political metaphor immediately calls to mind the late Nobel Laureate José Saramago's great companion novels Blindness (adapted for the screen by Fernando Meirelles) and Seeing. In the former a whole society loses it sight and descends into barbarism, in the later a whole society decides not to vote and the government declares a state of emergency. It also reminds me of Saramago's Borgesian-Kafkasque novel All the Names, with its cast of anonymous characters coming to be and passing away and its blurring of the demarcation lines between the living and the dead. Asked to name five films Saramago picked Herbert Biberman's Salt of the Earth, Fellini's Amarcord, a Pat and Patachon silent short, Renoir's La Règle du jeu and Ridley Scott's Blade Runner. Oppenheimer, for his part, unsurprisingly, cites Jean Rouche and, suprisingly, Bresson and Ozu as guiding spirits.

Susan Sontag said: "Transparence is the highest, most liberating value in art – and in criticism – today. Transparence means experiencing the luminousness of the thing in itself, of things being what they are. This is the greatness of, for example, the films of Bresson and Ozu." Oppenheimer may not replicate the 'transcendental style' Paul Schrader located in the work of Bresson, Ozu, and Dreyer, but he certainly seems to have followed Bresson's injuction to "empty the pond to get to the fish," absorbed his less-is-more, stripped-back, transparent economy of style, and learned from him all he sought about the dialectics of images and the grammar of silence. It's a shame neither Oppenheimer nor Sontag mention Dreyer who, even more than Bresson and Ozu, was a master of the revealing close-up. The Look of Silence is as full of riveting close-ups as it is of hovering, fluttering silences.

The great Spanish director Victor Erice, whose Quince Tree Sun (1992) transcends documentary and fiction, as films as various as Haskel Wesler's Medium Cool (1969) and Jem Cohen's Museum Hours (2012) do, said: "The music that I like best is the sound produced by the editing of all the images. The rhythm of the images has a music of its own and that's much more difficult than just placing music on top of a film." In The Look of Silence, Oppenheimer achieves a similar sense of musical visual rhythm through perfect, patient pacing while simultaneously creating a sound of silence that infuses the film with a quiet, steady melancholia. With the able assistance of sound editor Henrik Garnov, and the luxury of three-and-a-half months to edit and mix, he does so by a brilliant use of non-diegetic sound: the steady thrum of chirruping crickets stands in for metallic roar of traffic and we enter an enveloping pseudo-silence that somehow hints at justice and reconciliation.

The Look of Silence is a more contemplative, less ostentatious film than The Act of Killing, and all the better and more moving for that. It honours the victims of genocide and the classic conventions of ethical documentary to a far greater extent than its predecessor. Non-fiction filmmaking has always, from Flaherty forward, been in a state of flux, but, for good and ill, Joshua Oppenheimer has accelerated the contemporary trend towards new kinds of mixed, hybrid documentaries. This formal flexibility is a double-edged sword that both increases the reach of documentary and does damage to its duty to inform. If The Act of Killing represented the apotheosis of blurred boundaries between narrative and non-fiction there remains, nonetheless, considerable confusion about the difference between spurious notions of objectivity and documentary 'truth' on the one hand, and actually existing, verifiable fact on the other.

Oppenheimer himself says: "Journalism is there to tell us what we need to know. Art is there to tell us what we know, but don't discuss." It's a characteristically neat formulation, but, at its best, art actually forces us to question what we thought we knew, and if 'journalism' fails to tell us what we need to know, as it surely has, doesn't that place a greater burden on documentary film culture and leave 'art' looking comparatively slightly self-indulgent, even a tad shabby and decadent? Oppenheimer's films suggest two ready answers to that question: firstly, I wouldn't be raising it if it weren't for his artful films; secondly, and more importantly, they have spectacularly succeeded in changing Indonesian society. As an outsider, he has helped a divided people begin to look itself in the face and address its relationship to the past. It is to be hoped that Indonesians can build from that base, to amend their circumstances in the present and create a brighter, more honest future. As for thee and me, who knows what affect Oppenheimer's impressive films will have or have had on Western audiences. Perhaps the best we can hope is that the debates he has generated will continue and grow, and that we still have cinemas in which to watch his career develop. He has given himself a damn hard act to follow.

* Nick Fraser's thoughts on The Act of Killing:

http://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2014/feb/23/act-of-killing-dont-give-oscar-snuff-movie-indonesia

** Susan Sontag's Top 50 Films (1977):

1. Bresson – Pickpocket

2. Kubrick – 2001

3. Vidor – The Big Parade

4. Visconti – Ossessione

5. Kurosawa – High and Low

6. Syberberg – Hitler

7. Godard – 2 ou 3 Choses …

8. Rossellini – Louis XIV

9. Renoir – La Règle du Jeu

10. Ozu – Tokyo Story

11. Dreyer – Gertrud

12. Eisenstein – Potemkin

13. Von Sternberg – The Blue Angel

14. Lang – Dr. Mabuse

15. Antonioni – L'Eclisse

16. Bresson – Un Condamné à Mort …

17. Gance – Napoléon

18. Vertov – The Man with the [Movie] Camera

19. Feuillade – Judex

20. Anger – Inauguration of the Pleasure Dome

21. Godard – Vivre Sa Vie

22. Bellocchio – Pugni in Tasca

23. Carné – Les Enfants du Paradis

24. Kurosawa – The Seven Samurai

25. Tati – Playtime |

26. Truffaut – L'Enfant Sauvage

27. Rivette – L'Amour Fou

28. Eisenstein – Strike

29. Von Stroheim – Greed

30. Straub – … Anna Magdalena Bach

31. Taviani Brothers – Padre Padrone

32. Resnais – Muriel

33. Becker – Le Trou

34. Cocteau – La Belle et la Bête

35. Bergman – Persona

36. Fassbinder – … Petra von Kant

37. Griffith – Intolerance

38. Godard – Contempt

39. Marker – La Jetée

40. Conner – Crossroads

41. Fassbinder – Chinese Roulette

42. Renoir – La Grande Illusion

43. Ophüls – The Earrings of Madame de …

44. Kheifits – The Lady with the Little Dog

45. Godard – Les Carabiniers

46. Bresson – Lancelot du Lac

47. Ford – The Searchers

48. Bertolucci – Prima della Rivoluzione

49. Pasolini – Teorema

50. Sagan – Mädchen in Uniform |

*** Stefan Simanowitch's New Internationalist article "Suharto's Bloodiest Secrets:

http://newint.org/features/web-exclusive/2010/12/15/suhartos-bloodiest-secrets/

|