| "Whatever

you do, see Seven Samurai." |

| Life changing advice from a father to a son |

The year was 1979 and I was halfway through my three-year course at film school, and the passion for cinema that had pushed me down this route was about to be launched in a whole new direction. In the college holidays, I’d landed a job at Waterloo in South London, a mere ten minutes’ walk from the National Film Theatre (which has since been rebranded as the BFI Southbank). It seemed too good an opportunity for a film devotee such as myself to ignore, so I joined the NFT and began attending as many screenings as I could afford. I began on what was back then safe ground for someone raised on American and British movies, the result of being restricted to whatever was playing at local cinemas or on the comically small black-and-white TV that I had in my college digs. I thus initially gravitated to watching personal favourites like The Private Life of Sherlock Holmes and acknowledged classics like Citizen Kane on the big screen, while the first curated season I attended to was devoted to the films of American director Anthony Mann. Then, during one of these holiday breaks when I was staying with my parents, the latest NFT programme arrived, brimming with details of the following month’s films. As ever, it was chock full of titles both familiar and exotic-sounding, movies I’d never even heard of, let alone seen. My father, from whom I inherited my love of film, was interested in what they were showing. He glanced through the brochure and, on handing it back to me, said just six words that were to forever change my viewing habits and my perception of just what constituted great cinema:

"Whatever you do, see Seven Samurai."

This was, as it turns out, a great time to experience Seven Samurai [Shichinin no samurai] for the first time. Having been heavily cut to 158 minutes for its international release and further trimmed to 141 minutes in some European territories, it had then only recently been restored to approximately three-and-a-quarter hours, 15 minutes shy of its complete original version (I wish I could be more exact about the running time, but it wasn’t included on the handout given at the screening, which I still have it). Unbeknown to me, for reasons I cannot explain or excuse now, this restored print was first screened in the UK by the BBC as part of a World Cinema season. Having somehow missed that (my father clearly hadn’t), I was thus excited to discover that this same print was the one that the NFT would be screening. I thus bought my ticket for what I seem to remember was a Saturday or Sunday afternoon screening, then trotted up to London and took my seat in the auditorium of NFT1. I emerged into the foyer after convinced that the fabric of time had somehow been distorted. My watch assured me that I'd been sitting in the cinema for three-and-a-quarter hours, but I knew in my heart of hearts that it had really only been about forty minutes. I've seen the film many times since and the same thing always happens – time just disappears. I don't know another film that achieves this so invisibly. But then, there isn't another film on Earth quite like Seven Samurai.

I'm not going to pussyfoot around here – as far as I'm concerned, Seven Samurai is nothing short of perfect cinema, and I'm making that judgement on the basis of 20-something viewings over a period of 45 years, and the most recent viewing really was as thrilling as the first, especially given the quality of this new 4K restoration (I’ll get into the specifics of that below). I'm assuming that the vast majority of you reading this have at the very least heard of the film and that a sizeable proportion of you have seen it at least once. If you haven't, then put it at the top of your upcoming new year resolutions, and I mean the very top. Stuff the diet, forget about decorating the house or flat, and remember my father's wise words. For the very few of you who do not know the film I have no words of admonishment, just a genuine envy for the magical first viewing that lies ahead.

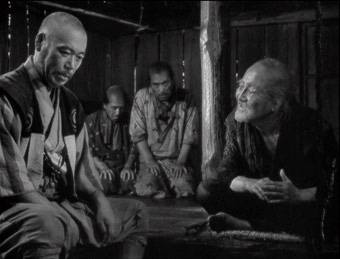

The plot has been reworked and recycled many times since and is deceptively straightforward in concept. In 16th century feudal Japan, the residents of a farming village being threatened by bandits decide to hire a group of samurai to protect them and their annual harvest. The problem is that they have no money with which to pay the samurai and can only offer food and lodging, hardly an attractive prospect for members of a proud warrior class. It takes just a couple of minutes of film time to set this up, something internationally celebrated director Kurosawa Akira does with blinding economy, and in seemingly no time four of the farmers, led by the anxious Rikichi (Tsuchiya Yoshio), set off to a nearby town in search of potential protectors. The recruitment of the samurai occupies a substantial proportion of the film's first third and is a constant delight, with each of the samurai introduced in a manner that is both memorable and reflective of their distinct personalities. Rarely have I seen such a range of characters so beautifully defined with such economy and speed, and every one of these scenes is packed with a wealth of inventive and entertaining detail.

The casting is sublime and crucial to the creation of such a range of vivid and memorable characters. Kurosawa favourites Shimura Takashi and Mifune Toshirō are perfect fits as the calmly knowledgeable and authoritative Kambei and the brash, excitable, wannabe samurai Kikuchiyo. But they are matched all the way by a supporting cast of talented actors who inhabit their roles so completely that it's genuinely hard to imagine them dressed in modern clothing. The youthful novice Katsushirō (Kimura Isao), the good natured Gorōbei (Inaba Yoshio), the ever-optimistic Shichirōji (Katō Daisuke), the cheerful Heihachi (Chiaki Minoru), and the introspective master swordsman Kyūzō (Miyaguchi Seiji) are all played to perfection, and I haven't even touched on the farmers and distinctively drawn bit-part players. It's also fair to say that this was the film that convinced me once and for all that if you're going to watch a film shot in a language in which you are not fluent then you should always seek out a subtitled rather than a dubbed version. So much of what makes the characters in Seven Samurai live so vividly on screen is down to how the dialogue is delivered, whether it be Katsushirō's overenthusiasm, Kyūzō's matter-of-fact minimalism ("Killed two," he states simply after returning from a one-man raid on the enemy camp before immediately settling down for a nap), or Kikuchiyo's boastful arrogance and, in two of the most justifiably famous scenes, tearful fury.

We are an hour into the film before the samurai reach the village that they have agreed to defend, and it still feels as if we're in the opening stages. Here, the blend of action, drama and humour is precisely balanced, and the cast of characters expands considerably to include a love interest for Katsushirō in the shape of pretty village girl Shino (Tsushima Keiko), a band of giggling children to form an audience for Kikuchiyo's clowning, and an ageing grandmother who only leaves her home after a bandit is captured, but you'll remember her long after the film concludes. The character interaction, of which there is great deal, also increases our understanding of, and attachment to, the individual samurai, but also to the farmers and their families, a frightened community forced to recruit men that they would normally fear, and, as we later discover, mercilessly prey on.

To reveal further plot details would take up time that would be better spent watching the film itself. Its length allows a depth of development that gives rise to narrative arcs within narrative arcs, and a level of character depth and interaction that no other action film has ever achieved. Indeed, so well developed are the dramatic and character elements that I have trouble, despite its breathless action sequences, actually categorising Seven Samurai as an action film at all, primarily because the is so much more to it than that. No argument here, Die Hard is a top-notch action movie, but its characters, as has become the norm for the genre, are little more than creatively and engagingly drawn cartoons. In Seven Samurai they are all recognisably human, drawn from history and legend but with the strengths, failings and everyday concerns of the common individual. And while the action scenes, when they come, are blisteringly handled, they comprise only a small portion of the film’s 207-minute run time. The rest of the film is devoted to telling the story, drawing the characters and charting their evolution, and exploring both the kinship and the conflicts that definite the complex and sometimes fractious relationship between the frightened farmers and the samurai who are willing to put their lives on the line to defend them.

The narrative surprises and rewards are timed to perfection, often layered to produce multiple hits from a single scene or story strand. A personal favourite occurs during the recruitment expedition (I'm avoiding specifics here so newcomers can experience the impact for themselves) when the farmer's rice supply is stolen and they are left with nothing with which to feed the samurai that they are trying to recruit. This leads to a moment of desperate, pathetic sadness, which is then shattered by a gloriously unexpected gesture of solidarity, all of which links directly back to an earlier scene of deep humiliation for the farmers that is transformed by the words, "I accept your sacrifice." Oh man, I get goosebumps just thinking about it. And there are so many such moments, running the full gamut from the intimate to the epic: Kikuchiyo's overenthusiastic participation in the village harvest; Katsushirō lying down in a bed of glowing white flowers; the battle flag that has Kikuchiyo represented by a triangle instead of a circle because, "You're so special"; Heihachi pausing his enthusiastic wood cutting to cautiously move his sword out of reach of the watching Gorobei; Kyūzō's Zen-like fascination with a single flower before suddenly leaping into action; farmer Yohei's despairing response to just about everything; the kidnapped (and we presume raped) farmer's wife who would rather die than face her husband again; the way Kambei's eyes rest on Kyūzō when all others are on his duel opponent; Kikuchiyo furiously lambasting his fellow samurai for their destructive behaviour and in the process revealing a crucial truth about his background, then later holding the baby of a slaughtered family and weeping, "This baby...it's me!" ...and there are at least a hundred more. To top it all, there's the final battle, an astonishing sequence that is steadily and excitingly built up to and fought in Kurosawa's beloved rainfall. It’s an action scene that has rightly earned its place as one of the finest in film history, a conflict staged on a grand scale that is as tragic as it is breathtaking, as sad as it is thrilling.

To be honest, I could write about Seven Samurai until there are enough words to fill a book so large that it would shatter all of the bones in your foot if you dropped it, but there are other reviews to write and I’m coming late to a party that began over half-a-century ago. This is a film that has been so widely analysed and written about that anything I might add (and, I'd venture, everything I've already written) has very likely already been said many by others before me, and probably in more detail and with greater eloquence (you’ll find plenty in the rich supplementary material that accompanies this release). The danger for newcomers approaching such a weight of critical analysis is that they can be frightened off by the expectations that it builds, which may seem to suggest a film they will admire for its craftsmanship rather than one they will enjoy, but such apprehension really is unfounded here. Seven Samurai is indeed magnificent cinema, but it is also stupendous entertainment – it tells a riveting story, is crammed with wonderful character interplay, plays successfully with just about every emotion you care to experience, and is consistent cinematic dynamite. The script is superb, the performances divine, the cinematography and editing both dynamic and purposeful, and the music score one of the most memorable in cinema history. Dramatically compelling throughout, the film is also rich in metaphor and subtext, commenting on Japanese society both past and (then) present and carrying worthwhile lessons for humanity as a whole. The action, when it comes, is still breathtaking today, with the swordplay breaking from the kabuki-inspired theatricality of earlier chanbara works in favour of a gritty realism that changed its portrayal in film forever.§

Most

will know that the film was remade in Hollywood as The

Magnificent Seven, whose status as one of the greatest

westerns has always bemused me. It's a well made and enigmatically

cast film, but I've yet to sit through it without being

constantly reminded how much richer and more entertaining

each of the scenes and characters are in Kurosawa's original.

And then there's Roger Corman's 1980 Battle Beyond

the Stars, a tacky, low budget science fiction

remake that nonetheless wears its cheese on its sleeve in

a way that is actually quite endearing.

I've

always had trouble narrowing my favourite films down to

anything below about three hundred titles, but know for

a fact that if I was forced to choose just five to spend

the rest of my viewing days with, then Seven Samurai

would definitely be in there. It

is, as I said, cinematic perfection, and more deserving

of the term masterpiece than almost any other so-classified film that comes readily to mind.

Seven

Samurai was only the second DVD title released

by Criterion when they made the switch from laserdisc and

one of the first DVDs I ever owned (a gift from Camus when

he was on an editing assignment in Amsterdam, if I remember

right). This early release included a restoration demonstration

that I gather was later removed after at the request of

Toho studios, as it reflected badly on their own less-than stellar preservation

efforts. Shown side-by-side with the original print, Criterion's

efforts were impressive, with large numbers of blemishes

removed, but the resulting restoration still showed

considerable wear and tear in the shape of vertical scratches,

dust spots and frame flicker. The improved sharpness and

strong contrast were a revelation to those of us new to DVD

at the time, and still hold up well today. However...

There

have been considerable improvements in digital repair and

enhancement technology in the intervening years (the first

Criterion version was released back in 1998) and anticipation

levels shot up here on the news that Criterion were to have

another go at Seven Samurai. And the result

is nothing short of stunning. Yes, there is still some visible

damage and flicker, but the vast majority of it has been

rendered virtually invisible, with dust spots rare and scratches

even rarer. The contrast range is glorious, more subtle

than on the original release with more shadow detail, but

still with solid black levels. The degree of detail in

some shots is astonishing for a once damaged film of this

vintage. Even if you have the original release, the improvements

to the picture alone make this an essential purchase. The

1.33:1 framing is slightly windowboxed to combat the overscan

on CRT TVs. The film is spread over two discs to keep the

bitrate as high as possible.

The

original Japanese mono soundtrack has also been cleaned

up further, removing the (albeit subtle) hiss and crackle

that was audible on the earlier release. The limited dynamic

range still betrays the film's age, but this never feels

like a compromise and is as good as the film is likely to

sound. The Dolby 1.0 mono is joined by a new Dolby 2.0 surround

mix that although pushes some of the ambient sound around

the room, but has the detrimental effect of breaking up and

distorting the dialogue, rendering it considerably inferior

to the mono track.

A

new English subtitle track has been included that for my

money loses some of the poetry of the earlier and more widely

recognised translation included on the first release. Thus

Heihachi's amusing explanation his approach to killing enemies

– "Well, it's impossible to kill them all...so I usually

run away" becomes "There's no cutting me off when

I start cutting...so I make it a point to run away first."

Not only is the language changed here, but the inference

of the dialogue is different. Indeed, Joan Mellen at one

point quotes Kyuzo's minimalist response to defeating two

bandits on his one-man raid as "killed two," which

is exactly as it was subtitled on previous prints (and which

I also quoted above), rather than the newly expanded "Two

more down" on this version. (For the record, Kyuzo

actually says "Futari," meaning just "Two

(people).") More anachronistic is the inclusion

of modern slang, with the newly confident farmers describing

the bandits as "wimps" and the film's only swear

word – chikkusho – given the translation "Hot damn!"

(For the record the word is variously translated as "dammit,"

"slut" (when referring to a woman) and "shit"

– the previous subtitle translation went with "sheeyit!")

I'm always a bit nervous about so-named 'expert' commentaries,

especially those on US DVD releases, which although often

fact filled are sometimes delivered in the manner of a dreary

university lecture, without the passion, memories, and anecdotal

asides that make the best filmmaker commentaries so appealing.

Good writers do not always make engaging talkers, especially

when they are reading from a pre-prepared script, and even

when they have interesting things to say, their delivery

can still send you into a snooze.

Criterion's

3-disc release of Seven Samurai boasts

two such commentaries, both new to this release. The

first, a so-called Scolar's Roundtable,

presents an interesting solution to the potential problem

of listening to a single academic talk for three-and-a-half

hours. Structured in the manner of a relay race, it has

one scholar talk for 40 minutes or so and then hand over

to another for the next section. The writers in question

– Stephen Prince, David Desser, Tony Rayns, Donald Richie

and Joan Mellen – are all recognised experts in their field

and there is plenty of interesting information served up,

although there's also a great deal of pointing out the obvious,

from camera shots ("Kurosawa cuts to close-up here..."

– I know, I can see it on screen!) to what the characters

are doing or feeling. It's actually worth putting up with

this to get to the good stuff, and film students should

have a ball with this. In terms of delivery, Stephen Prince

is the liveliest and the emminent Joan Mellen the sleepiest-sounding.

Richie recalls an engaging anecdote that even he at first thought

was a dumb answer to a dumb question, but has since realised

its truth – when he asked Kurosawa what his films were about,

he got the response, "Why people aren't nicer to each

other?"

The

second commentary is by Michael Jeck,

who also has some interesting things to say about the film,

Kurosawa's life and career, the performances and especially

the film's only swear word (see above), but not enough to

fill the film's running time, resulting in plenty of pointing

out the obvious and a few silent moments – they do not last

too long, but are broken with occasionally frivolous comments

on the action or characters.

The

other extras are spread across the three discs.

Disc

1

There

are 3 trailers and one teaser, all Japanese originals. Trailer

1 (4:10) is for the restored print and carries

a prologue gives away part of the ending. Trailer

2 (2:57) is presented without sound, which

has been lost, and is of particular interest, combining

film extracts with costume design paintings, behind-the

scenes footage, and shots of the cast performing in costume

against a blank studio background. Trailer 3

(2:43) is the most conventionallly structured of the three. The Teaser (0:40) for a "final theatrical run" and is heavily

windowboxed for reasons unspecified.

The

Production Gallery consists of

a number of behind-the-scenes stills and film posters from

around the world. It has to be said that the Japanese posters

are far and away the best.

Disc

2

Akira

Kurosawa: It is Wonderful to Create! (49:08)

is part of a Toho Masterworks series, and includes interviews

with a number of Kurosawa's key collaborators and archive

footage of the man himself, including brief interview snippets.

This is a very enjoyable and scholastically invaluable piece that covers

a lot of ground from the viewpoint of those who were there,

and it's also great fun in places. Obviously this is in

Japanese with optional English subtitles – only the detailed

captions that accompany some interviews are not translated.

Disc

3

My

Life in Cinema: Akira Kurosawa (115:52) was

shot for the Director's Guild of Japan in 1993 and comprises

a video interview with Kurosawa conducted by fellow filmmaker

Oshima Nagisa. Kurosawa talks in great detail about his

early life and his film career and I do mean great detail

– this is a near two-hour interview shot with just two cameras

with only the occasional slow zoom or cut to close-up or

out two two-shot to provide visual variety. Playing as a

more relaxed take on the BBC's Face-to-Face format, this is nonetheless an invaluable piece, probably

the most comprehensive interview with Kurosawa committed

to either tape or film and crammed with interesting information

about his life, work and opinions. His notebook entry, made

when he was still an assistant director, that Japanese films

needed to be "more dynamic," is a particularly

telling comment in light of the work he later became famous for.

Seven

Samurai: Origins and Influences (55:09) is

a documentary created specifically for this DVD release

that looks at the history of the samurai in Japanese life

and art, samurai films and literature and its specific realisation

in Kurosawa's masterpiece. Built around interviews with

the Scholars' Roundtable participants and Satō Tadao, probably

Japan's most respected film critic and author of several

authoritative books on Japanese cinema,* there is some overlap

with the commentary, but this is a well edited and enjoyable

piece that would serve as a fine introduction to those new

to Japanese history and culture and the Jidaigeki genre.

Finally

there is a Booklet of the sort

you'll find in Masters of Cinema releases, containing eight

short essays on the film and Kurosawa, including contributions

from filmmakers Arthur Penn and Sidney Lumet and Toshiro

Mifune's own recollections of the shoot.

What

more is there to say? One of cinema's most glorious works

is given superlative DVD treatment, once again establishing

Criterion as the leaders of the pack. Despite the cost of

importing the disc, I can't recommend it highly enough.

Just marvellous.

The Japanese naming convention of surname first has been used for all Japanese names.

|