"A thought which forms. A thinking form." |

Godard |

"When you look back at the history of cinema; first it

was silent, then it started to speak, then, in the Sixties,

it started to think about the nature of itself." |

Bertolucci |

Earlier this year the Cannes Film Festival celebrated an important aspect of its illustrious past by commemorating the 50th anniversary of Critics' Week. The Festival also demonstrated its vivacity by establishing a precedent: at its red carpet opening ceremony Bernardo Bertolucci was awarded the Festival's inaugural honorary Palme d'Or. Bertolucci was presented with that lifetime's achievement award by the President of the Festival Jury, Robert De Niro – who starred in Bertolucci's anti-fascist epic Novecento/1900 (1976) alongside Laura Betti, Gerard Depardieu, Burt Lancaster and Donald Sutherland. There can have been no more apt or appreciative a recipient than Bertolucci, who added it to the honorary Golden Lion awarded to him by the Venice Film Festival in 2007. Bertolucci describes himself as a "pure cinephile" turned "practising cinephile." His requited love for French cinema, in particular, is evident throughout his highly autobiographical second feature, Prima della rivoluzione/Before the Revolution, which won the Critics Award at Cannes upon its release in 1964.

Before the Revolution, like Bertolucci's most recent film The Dreamers (2003), combines love of cinema, radical politics and transgressive sexuality. Set in Bertolucci's native Parma in 1962, the film is an exploration of political doubt and the illusive freedoms of illicit love. Bertolucci's alter ego, Fabrizio (Fransesco Barilli), is a gauche upper-middle class dreamer cloistered in affluence, thrashing around in a youthful struggle to define himself against his family and society. As the film begins, he scours the city for his intended bride, Clelia (Christina Pariset), for one last look at her, as he prepares to break decisively with his bourgeois past and defy his predestined future. He finds Clelia in a church, where the hammer and sickle, and the clash of ideologies, are symbolically picked out on liturgical statues. Fabrizio's incipient rebellion coalesces around his hostility to organised religion and he seems set to choose Communism over Catholicism, which, for him, signifies "every privilege, every surrender, every subjugation." His search for meaning, identity and experience is played out through a flirtation with political commitment and an affair with his alluring, if neurotic aunt Gina (Adriana Asti). When his best friend, Agostino (Allen Midgette), appears to commit suicide, Fabrizio's emotional and political immaturity is exposed. Unable to commit either to romance or revolution, he spends the rest of the film in a delirium of indecision. Fabrizio merely dabbles in politics and love.

Gina is as aimlessly louche and adrift as Fabrizio. Her life in Milan, she tells him, is empty: she takes three baths a day, cries, laughs, plays at thought transmission, otherwise – "nothing." As bored with Milan as Fabrizio is with Parma, prone to panic attacks and midnight calls to her psychoanalyst, she seeks distraction in her nephew, and he in her. Both know that the relationship cannot last, but it provides solace while it lasts. It offers relief from introspection and boredom and solidifies into a detached sort of love. They share moments of real tenderness and erotic charge, but both are too self-absorbed to transform their transient affair into anything more binding. Gina's sexual liaison with a stranger spices the dying relationship up but its revivification is temporary. As the affair unravels, Fabrizio and his Marxist mentor, Cesare (Morando Morandini), track Gina down to her friend Puck's estate on the banks of the River Po. When Fabrizio quarrels with Puck, Gina slaps her jealous nephew and the relationship is over. Ultimately, neither Gina nor Cesare can rescue Fabrizio from himself. To his family's delight, he conforms, and returns, relieved, to Clelia and his class.

Bertolucci was just 23-years-old when he made Before the Revolution. With its jump-cuts and close-ups, its shifts of focus, its variegated editing patterns, its modish deployment of pop music, its fascination with city streets, and, above all, its discursive, declamatory style, it feels like a film of the nouvelle vague translated into Italian. It is nothing if not an encomium to the French New Wave. The film's skippy inventiveness speaks of Godard, its elegant black & white cinematography and political seriousness of Resnais and the Rive Gauche. At a press conference in Rome for his first feature, La Commare secca/The Grim Reaper (1961), Bertolucci told Italian critics that they should speak in French " . . . because French is the true language of cinema." The resultant wounded pride partly explains why Before the Revolution received a hostile reception in Italy upon its release. Bertolucci's respect for French cinema, repaid in kind by the critics of Cahiers du cinéma, also explains why the film was so well received in France and why Bertolucci was so enthusiastically applauded at Cannes when he collected his honorary Palm D'Or.

Languid and thoughtful though it is, this film about a man in his early twenties, by a man in his early twenties, displays all the febrile energy, improvisational daring and excited cinephilia characteristic of Bertolucci's French contemporaries – Chabrol, Demy, Marker, Godard, Resnais, Rivette, Truffaut and Varda. From Parma and Roma, Bertolucci looked respectfully, even enviously to Paris, where young critics-turned-cineastes were using young actors to make films for young audiences. The respect was mutual. Bertolucci was warmly welcomed into the Parisian cinephile fraternity. Most of the directors most admired by the Cahiers critics – Bergman, Bresson, Hitchcock, Lang, Mizoguchi, Ray, Renoir, Rossellini, Welles – grew fond, in their turn, of the Young Turks. Again, the respect was mutual. It amounted to a series of successful father-son relationships within the family of cinema. More precisely, it was a series of surrogate father-son relationships, as the experienced masters often replaced actual fathers for the young directors. François Truffaut epitomises that tendency. As German film critic Thomas Elsaesser notes in his essay Cinephilia or the Uses of Disenchantment, Truffaut was "fatherless but oedipally fearless." His insolent oedipal revolt against the 'cinéma de papa' represented a rejection of papa as much as a declaration of war on the New Wave's cinematic enemies.

An episode in the career of Truffaut's friend Godard highlights a search for surrogate fathers that was particularly intense for the postwar generation. In 1963, Fritz Lang appeared in Godard's adaptation of Alberto Moravias's novel Le Mépris/Contempt. A year later, Cahiers critic André Labarthe – who played Paul in Godard's Vivre sa vie/My Life to Live (1962) – filmed a riveting conversation between Godard and Lang. The resultant film was released under the title The Dinosaur and the Baby. Godard looks fresh-faced but he was already in his early thirties, so hardly a "baby." And Lang was no dinosaur, even if his career was ending as Godard's was beginning. Ever aware of the camera, deploying the skills he picked up in his PR days, Godard smiles demurely as he asks Lang what it feels like to be an older director – "a dinosaur," Lang interjects, "a dinosaur." Unflustered, Godard says that what strikes him about Lang's work is his sense of youth; he is always interested in the new and in new problems. Lang replies that their art, the art of cinema, is not just the art of the century but also that of young people. Godard, clearly delighted, says: "You think it's the art of youth. Me, I think that too."

An extract from that conversation appears in Emmanuel Laurent's documentary on the friendship between Godard and Truffaut, Deux de la vague/Two in the Wave (2011). That film also includes a revealing interview with Truffaut, in which he discussed the ardent cinephilia of the New Wave. He says: "I think this intense contact with film is an apprenticeship. People say the New Wave is inexperienced. It's made up of people coming from all walks of life. You find in its rank assistants and scriptwriters . . . and people like me who had no experience aside from having watched thousands of films." My italics emphasis an aspect of the New Wave that equally applies to Bertolucci, that process by which they learned how to make film by watching each others' films and those of the masters. These, then, were young filmmakers learning their craft, so the autobiographical and aesthetic were, inevitably, enmeshed. They frequently expressed their cinephile enthusiasms in quotation marks.

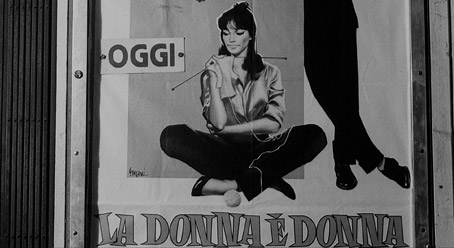

Before the Revolution is as packed with cultural citations as a film by Godard. In many ways it is a film by Godard, just as The Grim Reaper is, essentially, a Pasolini film. The 25 April, Italy's contentious "Day of Liberation," is cited, as are the anti-Fascist uprisings of July 1960. Bertolt Brecht appears on a poster too, but the references are primarily cultural not political. Early in the film Bertolucci tips his cap to Fellini's famous aerial sequence from La Dolce Vita (1960), circling Parma and the Po without Christ. He later reworks Anna Maganani's telephone conversation from Rossellini's L'Amore (1948) and winks at Antonioni by combining alienation, architecture and haute couture. The spirit of Pasolini is also present throughout the film, particularly in the scene after Agostino's drowning that features Enore (Guido Fanti) and his brother. But, although, the film acknowledges its roots in Italian cinema and its indebtedness to neo-realism, it owes more to the French cinema and the New Wave. Again, it shows that debt partly through quotation. Before the Revolution is a Russian doll of references, containing circular references, references hidden within references. When, for example, Gina evokes Jeanne Moreau in Truffaut's Jules et Jim (1962) by playing with glasses, she simultaneously reminds us of the moment in Godard's Une femme est une femme/A Woman Is a Woman (1961) when Jean-Paul Belmondo meets Moreau in a café and asks her how Jules et Jim is going. Perhaps Bertolucci was paying homage to Jean-Pierre Melville when he has Cesare read to schoolchildren from Moby Dick. After Fabrizio attends a screening of Godard's Une Femme est une femme (1961), he discusses the film with a cinephile friend – played by Bertolucci's cinephile friend Gianni Amico, who scripted that scene. The friend famously declares, "One cannot live with Rossellini" and admits to having seen his Viaggio in Italia/Voyage to Italy (1954) fifteen times. He also paraphrases Godard's aphorism that "Tracking shots are question morality," itself an inversion of the original comment by fellow Cahiers critic Luc Moullett that, "Morality is a question of tracking shots."

The use of quotation reveals the tension between the competing influences of Pasolini and neo-realism on the one hand, Godard and the New Wave on the other. The tug of those different influences pulls the film out of shape at times but, happily, even that jagged unevenness generates excitement. The film regularly slips its neo-realist anchor to sail the uncharted, choppy seas of cinematic invention. It has to be said, though, that the influences of Pasolini and Godard do damage to the film as well as complement it. In particular, Bertolucci's decision to use non-actors, a decision based on his admiration for Pasolini and respect for his ideological position, doesn't always pay off. Francesco Barilli as Fabrizio, is humourless and immutable, his movements as starched stiff as his shirts. During the scene in which he feigns pain as he recites from The Communist Manifesto, our pain, unlike his, is all too real. His performance reminds me of a comment Pauline Kael made about Charlton Heston: 'He can't open up; his muscles have his personality in an iron grip." Which, in Barilli's case, begs the question, what personality? To give Barilli the benefit of the doubt, let's assume that Bertolucci demanded a dour performance befitting an earnest, thoughtful young man. In which case, Bertolucci is to blame for an ill-advised casting decision and shoddy direction. Cecrope Barilli's acting is equally mediocre. Barilli Senior almost ruins a wonderfully lyrical ode to the River Po by flapping his arms with all the grace of a windblown straw scarecrow swivelling on its pole. Godard described Á Bout de Souffle/Breathless (1959) as a documentary on Jean Seberg and Jean-Paul Belmondo in a film by Jean Luc-Godard. In the case of the Barillis, the camera simply documents bad acting and poor direction. From here on, I intend to deploy the phrase "a case of the Barillis" to describe second-rate performances. Fortunately, Adriana Asti, the one professional actor in the cast, is superb when she isn't overacting, Morando Morandini's understated acting is as wonderful as his name, and the rest of the cast are excellent.

Of course, the quotations in Before the Revolution are literary as well as cinematic. The film takes its title from a remark by French Republican diplomat Talleyrand, who Marx bracketed with Bismark and Metternich as one of the three "Gods" of 19th Century Europe, and who broke with Catholicism to embrace the cause of revolutionary France. His comment is presented here as: "He who has not lived in the years before the revolution cannot know what the sweetness of living is." The suggestion is that life is never so intensely felt and lived as during times when hope prevails and everything seems possible. The epigram also hints that Fabrizio will never again feel as fully alive as he was while in love with Gina and wide-awake within his own emotional revolution. Times when vibrant Utopian possibilities quiver on the verge of fulfilment can, after all, be likened to the moment of falling in love, with its pure promise of complete happiness. Talleyrand's actual comment was recorded by erstwhile Prime Minister François Guizot in his memoirs as, "He who did not live during the years around 1789 cannot know what is meant by the pleasure of life." The times before the revolution are implied here too, but the emphasis is equally on the revolutionary moment itself and on the years after the Bastille fell. In the context of Before the Revolution, the difference is significant.

That referential slippage above is typical of the process of Chinese whispers that can distort quotation. Another example, one that sends shivers down the spine occurs when Fabrizio berates Puck for his insincerity. The landowner shrugs his accusations off by saying: "one inherits attitudes." Fabrizio, his Leftie loins stirred for once, says sarcastically (according to this translation): "Yes, habit can justify anything – even Fascism, Franco, Socialism." What?! The script, and Fabrizio actually say: " . . . even Fascism, Franco and Racism." It is hard to believe that a translator can have so completely misunderstood Fabrizio, Bertolucci and the film, and have misheard so spectactulary. Bearing in mind that critics take quotes from the translations presented on trust, this is no small matter. For the record, Bertolucci's heart was always on the Left. He didn't join the Italian Communist Party (Partito Communista Italiano/PCI) until 1968, but I'm sure he'd have been delighted had the Italian people risen as one to create Socialism, and equally delighted if it proved habit-forming!

When he made this film, Bertolucci was a critical outsider. He caricatures the Bolinger Bolsheviki by placing Cesare, presumably with a group of comrades, in a box at the opera. He also takes a dig at Stalinist myopia when Cesare says: "I've decided that there's only one sort of person to talk to: someone who shares one's ideas." It's a telling criticism of vanguardism. Elsewhere, Fabrizio expresses despair at a lack of popular revolutionary consciousness, revealing an attitude common among theory-and-book-bound bourgeois Marxists. It was that same mindset that Bertolt Brecht detected among East German advocates of what Ernst Fischer called Panzerkommunismus, and which he skewered by suggesting that if the people had betrayed the government, perhaps the government should abolish the people and elect a new one. It is, for all that, worth reminding knee-jerk anti-Communists that the PCI, the wartime party of the Italian partisans and scourge of Fascism, was a formidable force in Italian politics at the time Before the Revolution was made. It was even more popular then than the French Communist Party (Parti communiste français, PCF), which also commanded widespread support as the 'party of 75,000 martyrs' and bedrock of the Resistance. It is worth remembering, too, that, even or especially after the Bay of Pigs invasion of 1961, the Cuban Revolution continued to represent a real reminder of Utopian possibilities to those, like Bertolucci, who espoused the politics of hope.

Bertolucci lifted the names Clelia, Fabrizio and Gina from Stendhal's novel The Charterhouse of Parma (1839) but Before the Revolution is no mere adaptation. Bertolucci did, however, feed elements of the novel's convoluted plot into his script. In Stendhal's sprawling epic, Fabrizio is an impetuous, narcissistic youth in flight from his stiflingly conventional family; Gina is his flirtatious but vulnerable aunt, in thrall to a forbidden love for her handsome nephew; Clelia is the vapid but beautiful girl with whom he falls in love. Despite the fact that Stendhal was 56-years-old when he wrote it, there is a breathless, infectious energy about the book. It is easy to see why the novel appealed to Bertolucci and easy to track its traces in Before the Revolution. Stendhal, who loved Parma and Italy as much as Bertolucci loved Paris and France, wrote it at a lick, in just two months. Bertolucci's film is infused with a similar sense of urgency and displays the same freewheeling verve and panache of Stendhal's novel.

Despite the similarities between Stendhal's novel and the film, Before the Revolution owes much more to Bertolucci's own life than to any work of fiction, cinematic or literary. If all Bertolucci's films, even The Last Emperor (1987), are uncommonly personal, his early films were intensely so. They were made, after all, when the European trend towards personalised cinema was at its most pronounced. This was a period when that trend fed, and was fed by the theories of authorship formulated by the critics of Cahiers du cinéma, a magazine that Bertolucci read from boyhood on. In addition, as Bertolucci absorbed and re-presented those cinephile influences his fraught inner life was, as I hope to show, shaping his cultural allegiances. It seems to me, then, that, wary though we should be of reductive readings that equate artists with their art, scrutiny of biographical detail is particularly useful in Bertolucci's case and can shed considerable light on Before the Revolution. Bertolucci's early films can usefully be read in Freudian terms but they are also bound up in politics. So, while focusing on the personal, we should keep a close eye on the political.

In the film's scintillating closing set pieces, the Communist Festival of Unity is contrasted with a Gala evening at an Opera House to emphasise inequality and Fabrizio's defeatist withdrawal from the cause. His politics are always merely theoretical and he must "speak like a book in order to sound convincing." He admits to Cesare that ideology is just a holiday for him. Fabrizio's political immaturity and indecision are Bertolucci's; neither character nor director has made politics his own and neither has quite found his own voice. When Bertolucci made Before the Revolution, under the intoxicated influence of Pasolini and Godard, he was still unsteady on his directorial and political feet. Fabrizio speaks for Bertolucci when he says, just before his capitulation: "I thought I was living the revolution, instead I lived the years before the revolution, because for my sort it's always before the revolution." Bertolucci has spoken eloquently about the difficulties faced by bourgeois Marxists; aghast at injustice, romantically attracted to the idea of emancipatory struggle, but firmly rooted in the wrong camp. Of course many millions would welcome the chance to choose between inherited wealth and rebellion. Bertolucci's circumscribed framing of revolutionary possibilities calls to mind the Arab proverb, "If the turbans complain of a slight wind, what must be the condition of the nether garments."

Before the Tunisian and Egyptian Days of Rage in January this year, few would have predicted the revolution that was to sweep the Arab world, a revolution against what the Algerians call hogra, "contempt." The Arab proverb above, often quoted when the citizens of Cairo rise against oppression to remind us that the peasants always have greater cause for complaint, has another relevance to Bertolucci. His politics and his poetry were both heavily influenced by peasant Communists during his boyhood in the Emilia Romagna countryside, where Antonioni was also raised. Whether or not Antonioni's documentary Gento del Po/People of the Po Valley (1947) influenced Bertolucci, he certainly drew on his childhood experiences of peasant life for his anti-Fascist epic 1900. His first-hand knowledge of the political struggles of Italian peasants shaped his politics. I believe it gave Bertolucci the kind of patience John Berger discerned in Antonio Gramsci, onetime leader of the PCI. Berger says of Gramsci: "He never forgot the background of an unfolding drama whose span covers incalculable ages. It was perhaps this which prevented Gramsci becoming, like many other revolutionaries, a millennialist. He believed in hope rather than promises and hope is a long affair." Much the same can be said of Bertolucci. Here, for once, he parts company with Fabrizio, who petulantly disavows politics, disgusted by embourgoisement and unwilling to wait for the 'great day' of revolution. Bertolucci, meanwhile, still insists that ALL films are political and he remains an articulate critic of Berlusconi. At Cannes he dedicated his honorary Palm D'Or to Woody Allen and Bobby De Niro, both of whom were present at the opening ceremony, but also to "all those Italians who have had the strength and energy to struggle, criticise and remain indignant."

At the time the film was made, Bertolucci was married to Adriana Asti, whom he met while working as Assistant Director for Pier Paolo Pasolini on Accattone (1961). Fabrizio's relationship with Gina reflects Bertolucci's with Asti, his first wife, and predicts its collapse. Asti, with her dark eyes, elegant features and black bob, was to Bertolucci what Anna Karina was to Godard. This is just one among many ways in which Bertolucci's art imitates his life. Another such moment occurs towards the end of the film when we are introduced to Gina's friend Puck, played by Franseco Barilli's father Cecrope Barilli. Puck is a landowner, as was Bertolucci's grandfather, and when Fabrizio takes Puck to task we can hear a grandson's rebuke. We can certainly add his grandfather to the list of men Bertolucci admired but struggled to define himself against. Three famous father figures left their mark on him, on Before the Revolution and, to varying degrees, all his early films: his own father, Attillio Bertolucci, obviously, but also Pasolini and Godard, his "two spiritual fathers."

Attilio Bertolucci, who died in 2001, was one of Italy's foremost contemporary poets and a gifted art historian, novelist and film critic. It was through him that Bertolucci discovered film. While the legendary 'young Turks' of the nouvelle vaugue were broadening their cinephile knowledge in the cinemas of Paris, the boy Bertolucci was watching much the same films with his father in Parma. While Godard, Truffaut, et al were honing their critical faculties at Cahiers du cinéma, Bertolucci was absorbing their ideas in the copies of the magazine that graced the Bertolucci family home. Bertolucci has said: "My father taught me to see, grasp, and love the cinema. To a great extent, my passion for cinema derives from his passion for it." Of course, father also introduced son to literature. Bertolucci has also said that he started writing poems to imitate his father, then switched to cinema in order to distance himself from him. Bertolucci, like Pasolini, was as precocious a poet as he was a filmmaker, winning prestigious literary prizes for his first collection, In Search of Mystery, while still in his teens. He commonly consulted Pasolini, rather than his father, for feedback on his completed work. This is the first incidence of Bertolucci replacing one father with another.

Bertolucci's father helped Pasolini get Accattone off the ground and Pasolini may have hired his son to work on that film by way of a favour returned. In fact, it may not have been as cynical a you-scratch-my-back-I'll-scratch-yours his relationship with Pasolini, a family friend, was already well established by that time. In Peter Cowie's wonderful book Revolution! The Explosion of World Cinema in 60s, Bertolucci recalls how he became involved with the film: "Pasolini was a very good friend of my father . . . For me he was a kind of mythical figure. My father was reading his poems and I was very impressed. He was one of the various 'father figures' I've had in my life. He was living in our building for a few years, and one day, when I was twenty, I met him in the lobby and he said: 'You want to make movies, right?' So I, who had done nothing at all, replied, 'Of course. That's my life!' So he said, 'Ok, you will be Assistant Director on my first film, Accattone'. I protested that I'd never done anything like that and he said simply: 'I've never been a Director either, so let's both start together'." Elsewhere Bertolucci has said: "He was just as much a virgin to cinema as I was. So I didn't watch a director at work. I watched a director being born." Godard was another director who Bertolucci watched being born. Interestingly, if unsurprisingly, Bertolucci also has clear memories of meeting Godard for the first time. He was introduced to him by Richard Roud at the London Film Festival of 1961, in the lobby of the hotel where the directors were billeted. Such was his reverence for Godard that he vomited. The great film critic Serge Daney, former Editor of Cahiers du cinéma and Cultural Editor of Libération, had an identical reaction to the shock and awe of first meeting Godard.

Bertolucci's fears of being cemented in his class are evident in Before the Revolution, which he has described an "exorcism" of those fears. It is revealing that he should utilise a term synonymous with the worst suspicious excesses of the Roman Church to describe a political problem, for he had to rebel against his Catholic upbringing as much as his class background. The Grim Reaper was set in the same lumpenproletarian milieu explored by Pasolini in Accattone, Mamma Roma (1962), and, to a lesser extent, Uccellacci e uccellini/The Hawks and the Sparrows (1966). His politics in this period resemble nothing as much as Pasolini's brand of poetic Marxism. Like Pasolini, his compassionate love of the urban poor arose partly from his nostalgia for the rural idyll of his childhood. Like Pasolini, he contrasted an idealistic, romantic Communism with a reactionary, stultifying Catholicism. The opening scenes of Before the Revolution, in which Fabrizio jogs toward the retreating camera while denouncing Catholicism as a political soporific and the Church as "the pitiless heart of the State," are Pasolini writ large. The marked homoerotic elements in the film, both between Fabrizio and Agostino and Farbrizio and Cesare, are also straight out of Pasolini.

If there is much food for Freudian thought in the idea of Bertolucci coming to Godard and Pasolini by way of his father, there is also psychological interest in the form of his break with Pasolini. As Mira Liehm has pointed out, Bertolucci regularly attended soirées hosted by Pasolini after he moved to Rome. Among those who attended were Sergio Citti, an illiterate builder who wrote most of the dialogue for Accattone, and who worked with Pasolini throughout the 60s; his brother, Franco, who played the title role in that film; novelists Elsa Morante, who had first championed Attillio Bertolucci's poetry, and Alberto Moravia, whose novels The Conformist and Contempt were adapted by Bertolucci and Godard respectively; and actresses Adriana Asti and Laura Betti, who fought and fell out over Bertolucci. We can only guess at the circumstances that lead to Bertolucci and Asti's removal from the group, but the fact that Betti didn't speak to the couple for years does suggest an emotional and sexual entanglement. It seems likely that the split was also connected to Bertolucci's need to break with Pasolini.

A tart tone of residual rancour is evident in Pasolini's essay of 1965, The Cinema of Poetry. Pasolini praises Before the Revolution for its "elegant, elegiac spirit" and compares Bertolucci with Antonioni and Godard, who figure alongside Pasolini as significant influences on the film. There is a sense of the settling of scores when Pasolini discusses Adriana Asti, Bertolucci and Before the Revolution in relation to Monica Vitti, Antonioni and Red Desert (1964). He says: "While in Antonioni we find the wholesale substitution of the filmmaker's vision of feverish formalism for the view of the neurotic woman, in Bertolucci such a wholesale substitution has not taken place. Rather, we have a mutual contamination of the worldviews of the neurotic woman and of the author. These views, being inevitably similar, are not readily distinguishable." Pasolini returns to the attack later in the essay: " . . . beneath the technique produced by the protagonist's state of mind – which is disorientated, incapable of coordination . . . the world as it is seen by the no less neurotic filmmaker continually surfaces."

It is hard not to a read an equally barbed, if less personal response to Bertolucci in one extended scene in Pasolini's The Hawks and the Sparrows. To some extent, Bertolucci lacked the courage of his convictions as surely as Fabrizio does. This lack of courage reveals itself in Bertolucci's decision to show only the preparations for the Festival of Unity, just the before. In The Hawks and the Sparrows, on the other hand, Pasolini devotes considerable screen time to documentary footage of the funeral of Palmiro Togliatti – leader of the PCI from after Gramsci's imprisonment, by Mussolini, in 1927, until his death in 1964. That incredible footage is remarkable not only for the vastness of the crowds present but also for the sight of mourners filing past Togliatti's funeral: some giving the clenched-fist Communist salute, others crossing themselves with Catholic piety, others, remarkably, doing both.

In his excellent essay in the booklet accompanying this release, Pasquale Iannone reminds us that that much can be made of the way the Oedipus complex operates in Bertolucci's films. Meanwhile, Yosefa Loshitzky, in his book The Radical Faces of Godard and Bertolucci, brilliantly describes Before the Revolution as a film "before the analysis." As Bertolucci prepared to chair the first European Psychoanalytical Film Festival at London's Barbican Centre in 2001, he told the Observer: "There is all this killing of fathers in my movies. That's why my father told me a few years ago: 'You were smart; you've killed me many times without going to jail'." Sublimated patricide is certainly discernible in Before the Revolution. There are, for instance, clear traces both of Attillio Bertolucci and of Pasolini in the character of Farbrizio's teacher, Cesare. Oedipal elements are even more marked in Strategia del ragno/The Spider's Strategem (1970), begun after Bertolucci entered psychoanalysis. By the time he came to make Il Conformista/The Conformist (1970) though, he had, with the help of psychoanalysis and his preceding films, put his three fathers behind him. His first feature, La Commare secca, is so "Pasoliniano" that many critics have regarded Before the Revolution as his real debut. It certainly adheres to the autobiographical tendency of first works. Following that line of reasoning, we can equally argue that, because Before the Revolution and Partner (1968) were so Godardian, The Conformist was effectively Bertolucci's real debut, representing as it does a cathartic rebellion against both Pasolini and Godard.

Given the Oedipal twists and turns we have observed, it is no surprise that Bertolucci has been in psychoanalysis off and on since 1969. It is worth noting that Bertolucci's psychoanalyst appears on the credits for Ultimo tango a Parigi/Last Tango in Paris (1972). Equally noteworthy is Bertolucci's admission, in a frank interview about his childhood in 1973, that the thing he most remembered about his father was butter. History, sadly, does not record what, if anything, Bertolucci's psychoanalyst made of that astonishing comment. Whatever it suggests when placed beside the butter and buggery in Last Tango in Paris, it warns us to be sceptical with regard to Bertolucci's descriptions of himself. Bertolucci has always been ready to talk openly about himself and his films but he should not always be taken at his word. As Chris Marker says in Sans Soleil/Sunless (1983): "remembering . . . is not the opposite of forgetting, but rather its lining. We do not remember; we rewrite memory as history is rewritten."

Bertolucci has claimed that, when he and Dario Argento worked on the screenplay of Sergio Leone's Once Upon a Time in the West (1968), they smuggled quotations from Nicholas Ray's Johnny Guitar (1954) and other classic Westerns into the film, without Leone being aware of it. Leonne, for his part, claims that he knew full well and spotted each and every cinephile reference. Be that as it may, there is no doubting the passionate ardent cinephilia in which that story is rooted. Ray, after all, stood alongside Hawks, Hitchcock, Fuller and Welles as favoured Hollywood directors of the Cahiers critics (nicknamed the Hitchocko-Hawksians by André Bazin). In my recent review of Jean Epstein's Cœur fidèle/True Heart (1923) I noted a delightfully neat French cinematic tradition stretching through Jean Epstein, Jean Cocteau, Jean Renoir and Jean Vigo to Jean-Luc Godard and Jean-Pierre Melville. Bertolucci was nurtured by that tradition and that of Parisian cinephilia, then took them elsewhere. When he cites Vigo's L'Atalante (1934) and Hawks's Red River (1948) he was paying homage to those entwined traditions as well as those directors. Before the Revolution and Bertolucci's other early films effectively exported those traditions to Hollywood, where they were gratefully acknowledged and taken forward by Martin Scorsese, Jim Jarmusch and Frances Ford Coppola. Bertolucci, of course, was suckled on and disseminated the tradition of great Italian cinema.

One of the most moving passages in Godard's monumental L'Histoire(s) du Cinema (1988-1998) occurs in Chapter 3a – his paean on Italian neo-realism. To the haunting accompaniment of Riccardo Cocciante's exquisite song Nostra Lingua Italiana, we see clips from, for instance, Rossellini's Citta aperta/Rome, Open City (1945), De Sica's Ladri di biciclette/The Bicycle Thieves (1948) and Umberto D (1952), Fellini's La Strada/The Road and Notti di Cabiria/Nights of Cabiria (1957), and Visconti's Il Gattopardo/The Leopard (1963), before an iris close on the raven from Pasolini's The Hawks and the Sparrows. In the middle of one of the most brilliant pieces of film criticism ever written, Godard also says: "With Rome, Open City, Italy regained the right of a nation to look itself in the eye again. Then came the crop of great Italian cinema. But there is something strange here. How did Italian cinema become so great if no one – Rossellini, Visconti, Antonioni, Fellini – recorded sound with image? Only one answer: the language of Ovid and Virgil, of Dante and Leopardi, made its way into the image." Bertolucci had the courage, the hutzpah to continue that tradition, which, along with Godard, made its way into his images.

In her brilliant but gloomy essay A Century of Cinema (first published in 1995 in Frankfurter Rundschau, re-published a year later as The Decay of Cinema, in the New York Times), the late, great Susan Sontag, announced, after Godard, the death of cinema. Admirable films would continue to made, she said, but they would be exceptions to "an ignominious, irreversible decline," "heroic violations of the norms and practices that now govern moviemaking everywhere in the capitalist and would-be capitalist world – which is to say everywhere." Here she also implies that the politics of hope were dead too, but that's another argument for another time. Sontag, an ardent cinephile, felt that the imperial, religious, all-consuming love of cinema and cinema-going that inspired Bertolucci, Godard, Pasolini and countless millions was dead too. She concluded her essay by saying: "If cinephilia is dead, then movies are dead . . . If cinema can be resurrected, it will only be through the birth of a new kind of cine-love."

Those were the days before the digital revolution, before the internet revolution. Susan Sontag might have been more sanguine had she lived to see the new kind of cine-love that surrounds new festivals and films clubs, the explosion of internationalist online cinephile communities, and the cinephilia generated by home viewing platforms, video on demand, downloads and DVD/Blu-ray releases. In harnessing new technologies to revive the joys of watching films, contemporary cinephiles are simultaneously reviving that cine-love that reached its zenith in Paris in the '50s and '60s and enthusiastically practicing the aesthetics of improvisation so beloved of their Parisian cinephile predecessors. In New Grub Street, George Gissing's magisterial Victorian novel about the revolution in the publishing industry, a character, Marian Yule, says: "I love books, but I could wish people were content for a while with those we have already got." I couldn't agree more. I would agree even more strongly if the word "cinema" were inserted into that sentence in place of "books." Those who missed the screenings of this superb British Film Institute restoration of Before the Revolution early this year can settle down for a home viewing, ideally with cinephile friends, certain that they are in for a treat.

Before the Revolution has been released as a dual format package, featuring the film on both DVD and Blu-ray. Both have been transferred from the same master, but inevitably (and rightly) it's the Blu-ray that shines the brightest. This really is a lovely transfer, one whose tonal richness sings a hymn to pleasures of the monochrome image and whose level of detail, particularly on the opening aerial shots and just about anything involving buildings, textures or close-ups of faces, is sometimes breathtaking. The greyscale is particularly well judged, preventing any burn-out of highlights or loss of detail to shadows, and the black levels are for the most part spot on. The DVD is also impressive, but the level of detail is visibly inferior and the tonal range not as rich.

The Linear PCM 2.0 mono track on the Blu-ray does display the expected range restrictions, but is otherwise clear, and there is no evidence of distortion on music, no background hiss, and little of the expected treble bias. A very solid job.

Before the Revolution: Working Copy (Variations by the Author) (2003 – 31 mins)

Bertolucci's younger brother, Giuseppe, directed this riveting half-hour-long comparison of the working copy and final release version of Before the Revolution. This beautifully presented film demonstrates just how sharp Bertolucci's eye was, even at this early stage of his career, and how unerringly accurate his judgement of the perfect shot was. The rejected material is either too light or too dark, the final material all the more beautiful for being separated out from the body of the film. The working copy includes deleted scenes and improvised dialogue.

Original Trailer (1964 – 3 mins)

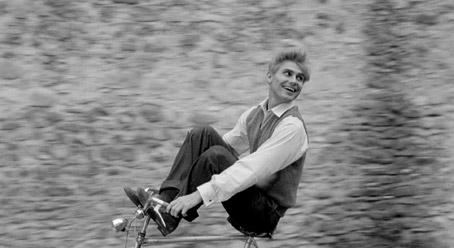

Whole essays could, and should be written about trailers. This one is standard, skilfully edited fare. It opens with the joyous, disturbing scene in which Agostino skilfully plays tricks on his bicycle for Fabrizio's amusement, in a kind of courtship dance that turns sour. Needless to say, the trailer emphasises, strictly heterosexual, sex. This, it announces, is an erotic love story set against the 'glamour' of opera. Politics and thought is sidelined, but, look, isn't the girl a beauty.

On the Set of Before the Revolution: extract from Cinema d'oggi (1963 – 4 mins)

This bite-sized extract from the TV series Cinema d'oggi/Cinema Today features an on-set interview with Bertolucci in which he deftly palms off loaded questions implying that he is contemptuous of the public. It is fascinating to see Bertolucci as a young man, full of swagger. He oozes the self-confidence that comes from inherited cultural capital and a sense of his own talents. The film was part of a series on 'uncompromising' young directors that also featured an interview with 'Prandino' Visconti, Luchino Visconti's nephew. Adriana Asti and Francesco Barilli shuffle around in the background, awaiting orders and, presumably, awaiting their turn.

Interview with Bernardo Bertolucci (Self Portrait) (2003 – 46 mins)

This candid, revealing interview was directed and conducted by Bertolucci's younger brother, Giuseppe. Bertolucci confesses to having "a very strange relationship" with Before the Revolution, so much so that he couldn't bring himself to watch it. He offers a clue as to why when he admits that Fabrizio was "like looking in a mirror . . . seeing myself representing a forced destiny which from the beginning of the film was written and decided." He quotes Glauber Rocha dictum that, "A director is somebody who finds the money to make a film." Then he produces some wonderful anecdotes relating to the production of the film, including his scrapes with the mafia in Palermo and his relationship with Gianni Amico. He reveals how important Godard, and Fellini's La Dolce Vita were to him: "It was the film that said to me, 'Get up and walk, become a director'." With his brother behind the camera, Bertolucci discusses Fabrizio's brother and reveals, shock-horror that "There really was a younger brother." Towards the end, Giuseppe allows himself into the film, to reveal that he'd hoped the incest had been able to continue!

The Workshop of the Young Masters (2003 – 26 mins)

This superb short contains revealing interviews with three of the most important contributors to Before the Revolution: its Editor Roberto Perpignani, legendary composer Ennio Morricone and Director of Photography Aldo Scavarda – who had earlier worked on Antonioni's L'avventura (1960). It is fascinating to hear this trio of talented artisans describe their craft and reminisce. None of these excellent men look ancient, which reminds us, as the title suggests, what a young, exciting team Bertolucci assembled back in 1964.

Bernardo Bertolucci in Conversation with David Thompson (2011 – 12 mins)

The most striking thing about the 12 minutes of this 'in conversation' piece, filmed in NFT1 in April, is the lack of conversation. David Thompson barely gets a word in. Some interviewees need coaxing, Bertolucci launches off on his own, unaided and uninterrupted. He describes himself as "a strong cinephile militant," who would fight for Godard and die on the barricades of Renoir. He reprises a few anecdotes that appear in Self-Portrait, talks about Godard again, and delivers a nice story about Christopher Isherwood in L.A.: apparently he responded to an enthusiastic Francophile with the witticism, "The word 'style' makes me hostile."

Booklet

This exquisite biblio opens with an excellent essay by critic, academic and broadcaster Dr Pasquale Iannone, who skilfully summarises the film while offering insightful background information. The 22-page booklet also includes an extract from Jean-André Fieschi's 1968 interview with Bertolucci, originally published Les Lettres Françaises under the title Bernardo Bertolucci: Before the Revolution – Parma, Poetry and Ideology. The icing on the cake is provided by Richard Roud's reaction piece on the film (from his Report from the Third Critics' Week at Cannes, 1964 for Sight and Sound) and Philip Strick's 1969 Monthly Film Bulletin review of it. Credits, stills and notes on the Special Features complete this collectable wee parcel of delights.

Before the Revolution is much, much more than an interesting, elegantly shot film by a precocious director. It is a passionate love story, a moving reference resource, a lament on the fragility of young ideals, an ode to lost innocence, a hymn to cinephile enthusiasm, and an accomplished work of psychological subtlety and political immaturity. As fascinating for its flaws as it is exciting for its successes, the film deserves to be seen and seen again. Bertolucci has made better films, but none more vivacious or stylish. The British Film Institute has, once again, delivered cinematic treasure at a price within reach of all. Highly recommended.

|