| |

"The old must make way for the new, especially when the old is suspected of senility." |

| |

Dr Murchison in Hitchcock's Spellbound |

| |

"A love of the cinema desires only cinema, whereas passion is excessive: it wants cinema, but it wants cinema to become something else." |

| |

Serge Daney |

The subject of Emmanuel Laurent's documentary Deux de la vague is the initially tender but, ultimately, catastrophic friendship between Jean-Luc Godard and François Truffaut. It places that friendship in the context of its times by casting a cursory glance over the complex histories of the film journal Cahiers du Cinéma, the movement we now know as La Nouvelle Vague, and Les Evénéments of May 1968. There are also two back-stories in the film that insinuate themselves into our thoughts as we watch: that of cinephilia itself, a passionate love of cinema at its most intense in post-war Paris, and that of actor Jean-Pierre Léaud, the embodiment of the New Wave – torn between the two directors as a child might be by the rancorous divorce of two parents, and indelibly scarred by the experience.

The film, written and narrated by former Cahiers du Cinéma editor Antoine de Baecque, immediately cuts to its punch line: the collapse of that friendship, like that of Sartre and Camus, in the face of irreconcilable political and aesthetic differences. It opens with a shot of de Baecque himself – at home and at work, we are lead to suppose, on the film's script. As the credits roll and de Baecque types, Godard recalls a comment made by his colleague and companion of 30 years, Anne-Marie Miéville, after Truffaut's death in 1984: "After the death of François, Anne-Marie Miéville told me, 'Now that he's dead, nobody will protect you. Since he was the only one of the New Wave who was accepted and tried, in a way, to join the Establishment'." That conversation points to Godard's lingering affection for Truffaut and hints at Godard's disappointment that he had failed to tug Truffaut to the left. It says much about Truffaut's sense of loyalty that, although the friendship fractured in 1973, the perception persisted that he would, nonetheless, spring to Godard's defence in a pitch.

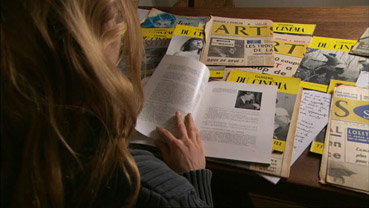

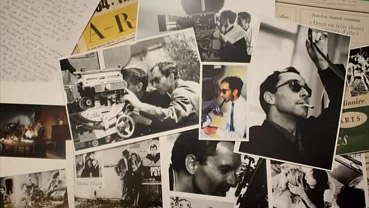

As the film begins in earnest we are introduced to Isild Le Besco, an upcoming actress who appears throughout, generally leafing through the wealth of press clippings, posters, photographs, magazines and memorabilia that inform the film. Laurent uses Le Besco, irritatingly, as a means of displaying that material and a pretty face. She is also present, presumably, to suggest that the film culture under consideration is now ancient history for her generation, a generation more familiar with TV and DVD than cinema. It may be no coincidence, then, that Deux de la vague feels as if it were made with TV or cultural studies classes in mind, and intended to educate Le Bescoe's generation. It is left to us to decide whether the film's reductive, painting-by-numbers approach is justified on those grounds.

Those hoping for a fresh, in-depth assessment of the films of the New Wave will certainly be disappointed. Deux de la vague is aptly as well as neatly titled for, no matter where we wish the film to roam, it remains, stubbornly, a film about two directors and two films: Les Quatre cents coups/The 400 Blows and À bout de soufflé/Breathless. That is all fine and honest in itself. The film works well on its own terms. We might, though, usefully heed Godard's command to remake films in our heads and bemoan a lack of daring and panache on the part of Laurent and de Baecque.

They are too determined to be pithy to offer much beyond generalisations and anecdotage. Similar accusations have, of course, often been levelled at Godard. Here de Baecque may have made more of Godard's two-year stint as a press agent for Fox; there was always a touch of the Sidney Falco in Godard's aphorisms. If Laurent and de Baecque did have an educational agenda, it fell far short of any ambition to describe how those films operate. Aside from fleeting references to lighter cameras, location shoots and jump cuts there is no attempt to analyse the films and little to trace the stylistic debt they owed others – notably Bergman, Hawks, Hitchcock, Renoir, Rouche, Rossellini and Welles.

There is no attempt, either, to assess key films of the New Wave such as Jacques Demy's Lola, Jacques Rivette's Paris nous appartient/Paris Belongs to Us, Claude Chabrols' Le Beau Serge, Agnès Varda's Cléo de 9 à 7, Chris Marker's La Jetée or, even, Alain Resnais' Hiroshima mon amour - a film that premiered beside Les Quatre cents coups in1959 and which, as Colin McCabe says in his excellent Godard biography, "showed that the New Wave had a historical significance and an aesthetic range that made À bout de souffle look like a teen flick."

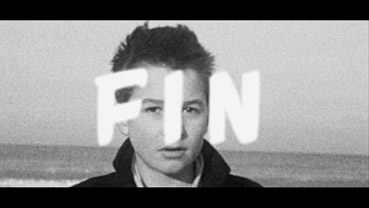

Fortunately, Deux de la vague springs to life whenever it allows the magnificent archive material to speak for itself. It does so immediately by cutting from Le Bescoe, first to Jean-Pierre Léaud as Antoine Doinel in the haunting closing scene of Les Quatre cents coups, then to an audience of stuffed shirts and fur coats applauding the film at the Cannes Festival. Of course, as that audience watched the waves ripple the beach in the closing scene of Truffaut's masterpiece, as they savoured the haunting melody that underscores the film and absorb Antoine Doinel's inscrutable final stare into the camera – FIN – they were also unwittingly witnessing and applauding the end of an era, their era, one being swept aside at that very moment by the inrushing New Wave.

If Laurent's documentary and Antoine de Baecque's script leave much unsaid and much to be desired, the depth of research apparent here is impressive and the footage found does much of their work for them. When the film manifests its redemptive virtues – canny editing combined with a collage of captivating archive imagery – it is superb. As it is when we see 14-year Jean-Pierre Léaud arrive at Cannes station in 1959 to take his place on the Festival podium and in history. In one of the film's many scintillating moments, the waiting camera captures Léaud between two worlds, boyhood innocence and imminent stardom. He walks down the platform, unaccompanied, carrying just a battered suitcase. Then he notices the camera. He smiles impishly at it, before catching himself, returning to his new role and walking on, all studied seriousness. As de Baecque says: "Actor and character are born together."

It is difficult for us, looking back over half a century, to imagine the explosive impact of Les Quatre cents Coups. One means of doing so would be to compare that moment with the arrival of the Sex Pistols and Punk, for there was a similar anti-establishment, punkish energy about the young Turks of the New Wave and their DIY ethic. Be that as it may, we can't as much as sniff the cordite without an understanding of Truffaut's position within French film culture and of developments in French film criticism. Again, to its credit, Deux de la vague deploys rare footage deftly to recapture the frisson of excitement surrounding the arrival of the New Wave and sketches that background neatly.

Crucially, de Baecque reminds us that Truffaut had been banned from the 1958 Cannes Festival following his frontal attacks on the film establishment in Cahiers du Cinéma and in Arts. In a series of combative polemics (most notably his seminal 1954 essay 'A Certain Tendency in the French Cinema' and his 1958 essay 'French cinema' is Collapsing Under False Legends') Truffaut had attacked the 'cinéma de qualité' or 'cinéma du papa' – a studio-bound, sterile form of film reliant on literary adaptation, star names and the ostentatious trappings of big budgets. It was an overfed, self-satisfied, stultifying cinema that corresponds to Andrew Higson's descriptions of British "Heritage" cinema.

When Truffaut attacked the Cannes Festival itself as staid and corrupt, it was the final straw for the old guard and his accreditation for the 1958 Festival was withdrawn. Les Quatre cents coups was only shown at Cannes after the direct intervention of André Malraux – as France's first Minister of Culture. Covering the 1959 Festival for Cahiers, Godard betrayed both his jealously and his delight at Truffaut's success when he wrote: "Les Quatre cents coups would at root be just another normal film, proof of Francois' talent, except that it exploded in the middle of the enemy camp, defeating them from within."

Fortunately for Godard, and for us, Truffaut's success had prepared the ground for Godard's, the following year, with À bout de souffle. Financed by Truffaut's father-in-law Ignace Morgenstern, Les Quatre cents coups recouped its entire budget from U.S sales alone, even before Truffaut's victory at Cannes. French box office sales had been falling alarmingly prior to Truffaut's debut, so the directors of the New Wave were welcomed into the fold, as saviours of French cinema. Producers like George Beauregard were soon falling over themselves to sign up young talent – until, that is, the novelty wore off and figures fell away, then the pack rounded on the New Wave again.

As Deux de la vague short changes us on the detailed analysis we might hope for from a writer with de Baecque's credentials, we should question those credentials. While the archive footage delivers fresh insights into Léaud, Godard and Truffaut throughout the film, those insights often occur in spite, not because of de Baecque's script. One moment early in the film is a case in point. We watch Truffaut and Léaud stroll the Croisette, awaiting the Jury's verdict, pausing to look up at a poster advertising Les Quatre cents coup. It is clearly what we might call a photo call. De Baecque, though, over eggs the pudding and tells us that, "They appear amazed by the film's poster." They don't. Truffaut and Léaud are playing to the camera, just as de Baecque is playing to the gallery. Truffaut even takes a sideways look at the camera and choreographs the scene, as if he himself were directing it. It is disingenuous to imply that the camera is catching a spontaneous, wide-eye reaction to fame and de Baecque has the skills to read the scene correctly. It is a cheap trick on his part. That scene reveals Truffaut's already sure sense of perspective, but it also reveals de Baecque's hack's eye view to a story and occasional tendency to bend or conveniently forget the facts when it suits.

There are several similar misreadings or deliberate distortions – call them what you will – in Deux de la vague. We have De Baecque to thank for the definitive biography of Truffaut (co-written with Serge Toubiana). He has also written a two-volume history of Cahiers du Cinéma and, more recently, published a voluminous, if pedestrian biography of Godard – so he should know better. De Baecque's shorthand style can be engaging but such 'slips' raise questions about his integrity or, at the least, his continued interest in the subject. While writing those and other books, de Baecque was editing Cahiers, then the cultural pages of the left-leaning daily Libération. Perhaps he is not so much bored as burnt out. Deux de la vague doesn't lack bounce but it leaves us with a sense that de Baecque is merely going through the motions for another fat pay cheque.

When de Baecque edited Cahiers, he did so under the dictatorial direction of ex-Maoist Serge Toubiana, who drove the journal toward the mainstream, dumbing it down and drawing its teeth. Cahiers du Cinéma is now a mere shadow of its younger, more daring self. It has none of the engagé political fervour of its 'red years' and is no longer the combative critical force it was in its 'yellow years' when Godard, Truffaut, et al were writing furiously for it. Deux de la vague betrays the same lack of bite as the later, glossier Cahiers but it still does a decent journalistic job of describing the milieu from which the New Wave sprang and in which the Godard/Truffaut friendship was forged.

It is worth emphasising, as film does, the extent of the support Truffaut offered Godard. Having paved the way for Godard's arrival Truffaut signed as co-guarantor, with Chabrol, for À bout de souffle. He also provided Godard with a ready-made scenario for the film, drawn from Truffaut's press cuttings on the real life Michel Poiccard case. Prior to gifting Godard his first feature, he had earlier given him his first significant short, Une histoire d'eau. Although Godard secured work on Cahiers through Jacque Doniol-Valcroze, a family friend, it was Truffaut who introduced him to work on Arts. Godard had a great deal to thank his friend for.

Godard hailed Truffaut as the better critic, while damning him for reading too many books. Truffaut hailed Godard as the better filmmaker: explaining his decision to co-finance Godard's Deux ou trois choses que je sais d'elle, he wrote, "Is it because Jean-Luc has been my friend for 20 years or because Godard is the greatest filmmaker in the world that I'm involved with his film? He is not the only director for whom filming is like breathing, but he is the one who breathes best . . . There is cinema before Godard and cinema after Godard." As to friendship, no contest: Truffaut was the better friend by far.

It seems certain that Godard and Truffaut first met either at one of the many ciné-clubs that proliferated in Paris in the immediate post-war period or in Henri Langlois' Cinématèque – which had first opened in Avenue de Messine in 1948. Antoine De Baecque suggests they became 'friends in cinephilia' at Eric Rohmer's Ciné-Club du Quartier Latin in 1949. What is certain is that they met in, and built their friendship around cinema. They did so at a time when French audiences were seeing, for the first time, the extraordinary Hollywood films they had been denied during the war. It was largely around those films that the Cahiers' young Turks – Chabrol, Godard, Melville, Rivette, Truffaut, et al – would build the set of ideas that formed their politique des auteurs.

German film critic Thomas Elsaesser points out that cinephilia, "the love that never dies," can claim the allegiance of three generations of film-lovers but has nowhere been more passionately defended than in Paris, where ideologically or aesthetically partisan groups divided up the city's cinemas like Chicago gangs during prohibition. It was a time marked by an intense, almost religious devotion to film in Paris. It was there that Sartre, Malraux and the young men later to form the backbone of the New Wave were being persuaded of the merits of cinema – at André Bazin's ciné-club beside the Sorbonne, at Langlois's Cinématèque, and elsewhere. It needs hardly be said that Godard and Truffaut were converted instantly, for life. It is symbolic of their obsession with cinema that Godard stole from his wealthy family to fund his films, while Truffaut stole to pay the debts of the ciné-club he founded when just 16-years-old. Both spent time in prison and the gleefully anarchic air of criminality that flavours both Les Quatre cents coups and À bout de souffle is partly rooted in those experiences.

Deux de la vague, advisedly, pauses to consider the importance of André Bazin. Bazin, who co-founded Cahiers du Cinéma with Jacques Doniol-Valcroze in 1951, was more than just the journal's golden pen and an intellectual mentor for the young Turks he referred to affectionately as the "Hitchcocko-Hawksians." Bazin articulated a coherent aesthetic of realism that they drew on and 'corrected' the wilder excesses of their theories of authorship, but he was also a father figure for them, particularly for the troubled Truffaut of those years. Traffaut needed such a figure more than most: shunned by his mother, he didn't learn that his legal father was not his biological father until he turned twelve. Cinema saved Truffaut, but so did Bazin. After his attempt to rescue Truffaut from a second spell in prison, after he deserted the army, he all but adopted Truffaut, who lived with him for much of the 50s. Bazin died on 11 November 1958, the day filming began on Les Quatre cents coups. In a special issue of Cahiers du Cinéma Truffaut wrote of Bazin: "He helped me make the leap from cinephile to critic, to director . . . He was the Just Man by whom one likes to be judged and, for me, a father whose very reprimands were sweet."

Another father figure and mentor to the young Cahiers' critics was Alexandre Astruc, who, in his essay "La Caméra-Stylo," demanded a new kind of improvisational writing and filmmaking, filmmaking as writing. That essay lead directly to the formation of the film club Objectif 48 by Astruc, Bazin and Langlois – the Holy Trinity for the young Turks. The birth of that club lead in turn to the 1949 Festival du Film Maudit in Biarritz – an alternative to Cannes designed to "measure, with purity and frenzy, the current battle lines on the field of cinematographic intelligence and sensibility." Godard and Traffaut attended. A camera catches them, in what de Baecque calls the "source image of a friendship, the first scene in a novel of initiation, the opening shot on a film about confederate camaraderie." The ground was prepared, then, for the arrival of the New Wave – enmeshed in the phenomenon of cinephilia initiated by Astruc, Bazin and Langlois and inhabited enthusiastically by their young disciples.

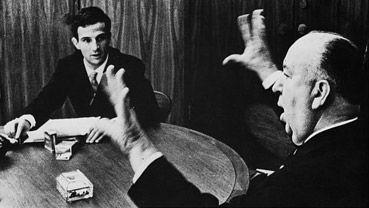

In covering that background and the explosion of the New Wave Deux de la vague occasionally lifts off to a higher plane. For anyone who delights in cinema, the central section of the film is a rare treat. This is where the archive material best works its magic. We see Claude Autant-Lara – Truffaut's bête noir, the voice of reaction – delivering an apologia for avarice. We see a vox pop of filmgoers delivering their verdicts on À bout de soufflé. Langlois talks about his mission to educate the eye and dismisses those who complained about the Cinématèque's habit of screening Buster Keaton with Czech subtitles: "If they don't get Keaton without subtitles, well..." Godard pulls his notebook out to quote Welles: "If we movie people want to be called artists, we must remember and respect this rule: any true moral standards imply a fierce resistance to tyranny." All the film's flaws are forgotten as the pleasures keep on coming. Jacques Doniol-Valcroze extols the virtues of the young Turks, Pierre Kast extols the virtues of Bazin, Godard praises Rossellini, Truffaut praises Renoir. Jean Rouche gives a master class in editing. The interviews with Godard and Truffaut that pepper the film are revealing and warming. Best of all, though, is an interview between Godard and Fritz Lang, in which they share their belief in cinema as a form for the young and the old master chuckles at the fact that Godard knows his films better than he does himself. By this stage we are ready to beg for more.

Unfortunately, what happens in Deux de la vague thereafter is, perhaps inevitably, an anti-climax. The film trots breathlessly through the 60s, pausing only to note, en passant, the tendency of the two busy friends to wink and nod at each other through their films. Then the film runs out of steam as it runs out of a story. More accurately it collapses under the weight of politics as surely as did the friendship it surveys. Having been comfortable while showing Godard and Truffaut unite against censorship, Laurent and de Baecque become uneasy when describing more incendiary struggles. As the two Turks stand shoulder-to-shoulder again – first in February 1968 in defence of Langlois, after he is removed from office by their old ally Andre Malraux, then, in May '68, to close the Cannes Festival down – the film retreats to safer ground. Quickly fleeing the political with their tails between their legs, Laurent and de Baecque nervously shift to the terrain of individual crisis, ending with the collapse of the Godard/Truffaut friendship and a reassuring reminder of more 'innocent' times by reviewing Jean-Pierre Léaud's career.

Perhaps de Baecque winds things down this way out of sheer embarrassment, after having delivered two of the most fatuous lines in modern cinema. "The images of May '68 seemed to be images from the New Wave," he says. We can only scratch our heads and wonder what images de Baecque had in mind. Perhaps he had confused images from the Godard/Marker Ciné-tracts – say those depicting the revolutionary use of cobbles stones – with earlier images of Claude Brasseur, Sami Frey and Anna Karina dancing modishly in Band à part? It is hard to say, and equally hard to know how to respond to the equally asinine comment that follows: "Those who fought in May 1968 did so imagining images from the films of Godard and Truffaut." It would be interesting to know what percentage of those who fought on the barricades, let alone what percentage of the 10 million French workers involved in the General Strike of May '68, that could be said of.

The film draws to a close with the depressing story of the implosion of the long-lasting friendship between Godard and Truffaut. As their letters, first published in 1988, become ever more vitriolic Godard and Truffaut stab at each other's weak spots, much as Burton/George and Taylor/Martha do in Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf? Godard's political position had cost him dear; doors were being slammed in his face. In 1973 – embattled, broke and isolated – he reached out to his old friend again. His stubborn pride and polemical honesty, as ever, get in the way. Godard cannot restrain himself; having branded Truffaut "a businessman in the morning and a poet in the afternoon," he asks for help while simultaneously accusing Truffaut of being 'a liar' and of making a dishonest film, La Nuit américaine. Truffaut replies, in a 20-page letter, accusing Godard of behaving like 'a shit' and of political hypocrisy – particularly over his failure to support Sartre, De Beauvoir and himself in their campaign to defend La Cause du Peuple. Truffaut writes: "I've always had the impression that real militants are like cleaning women, doing a thankless, daily but necessary job. But you, you're the Ursula Andress of militancy."

Deux de la vague rescues itself from its own worst aspects one last time by closing with a sequence of images of Jean-Pierre Léaud and ends with footage of a fresh-faced Leaud auditioning for his part in Les Quatre cents coups. In conversation after the London premiere of Deux de la vague Emmanuel Laurent told me that Léaud is now psychologically unbalanced, which makes that footage all the more poignant and heart-rending. The experience of playing Antoine Doinel throughout his career must have loosened the anchor of his sense of identity. His sense of self must have been equally eroded by the experience of working by turns for Truffaut and Godard, thus being bounced between two 'fathers' as well as between two essential characters: himself as loveable Antoine Doinel and Godard's version of him as a political militant.

Godard, like Léaud was indelibly scarred by those times. He would obviously have been wounded when Truffaut publicly denounced him in Cahiers du Cinema in 1980, saying: "Even at the time of the New Wave, friendship with him was a one-way street . . . one had to help him out all the time, to do him a favour and wait for a low blow in return." Yet Godard still misses Truffaut. He often seems like a man left alone in a darkened cinema, deserted by his times, his mentors, his art form and his friends – nowhere more so than in L'Histoire(s) du cinéma, a poetic film-essay in which he brilliantly brings Astruc's notion of the 'Caméra-Stylo' to fruition. Godard and Truffaut started writing for Cahiers when they were both just 21-years-old in the early 50s, so there is a tone of nostalgia and emotion in his voice as he mourns his lost friend and their cinephile youth in Chapter 3a – Une Vauge Nouvelle:

"One evening we turned up Chez Henri Langlois. And then there was light. Nothing to do with Saturday movies at the Vox, the Palace, the Mirimar, the Varieties . . . those films were for everyone. Not for us. Everyone but us. Because the true cinema was the kind that couldn't be seen . . . That was the only kind of youth . . . The children of the Liberation and the Museum . . . Langlois confirmed it . . . that the image is the domain of redemption and reality. We were amazed . . . We had no past. This man from the Avenue de Messine gave us the gift of this past, metamorphosised into the present . . . Becker, Rossellini, Melville, Franju, Jacques Demy, Truffaut . . . yes, they were my friends . . . (an image of Truffaut) Not to be. Nonetheless, I will never forget him."

It is a moving act of remembrance within a project of enlightening depth and extraordinary intellectual reach, the kind of project that Laurent and De Baecque come nowhere near close to emulating in Deux de la vague. Their film insists less is more but, despite its moments of magic, it needed to be far longer and more inventive in order to do its subject matter justice.

It's always a difficult call to accurately judge the quality of a transfer of a film constructed primarily from film extracts and archive material, as precious few, if any, have the funds to digitally restore the material they buy in and tend to have to live with the supplied condition. That said, the extracts included here are generally in good shape, some of them very good, and although the archive interviews are more prone to damage, even they are in reasonable condition. The litmus test is the new material, which is shot on digital video and is looks fine.

The Dolby 2.0 stereo soundtrack is likewise subject to some variance in quality depending on the source material, but mostly fares well, with no obvious damage and only a slightly tinny rings to some of the older film extracts and interviews. The narration and live sound of the new material is always clear.

The English subtitles are clear but fixed, a rarity on a modern DVD release.

The only 'extra' feature on this DVD is a trailer plugging the film. A small booklet containing images, a collection of short essays and a filmography would have enhanced its appeal. It would also have gone some way to suggesting that the producers of the film valued their project as a work of lasting significance. An interview with Emmanuel Laurent and Antoine de Baecque on the making of the film might have been worth watching too.

Intent of emulating the dynamic brio of the New Wave, Deux de la Vague sacrifices seriousness and the subtleties of psychology for a snappy, sometimes vapid delivery that jars at times. It shies away from the dangers of politics and the challenges of analysis, but redeems itself by dipping deep into the vaults and uncorking some mouthwatering vintage footage. It positively fizzes as an intoxicating collage of rare photographs, cuttings and clips pours from the screen. For all its failings the DVD of Deux de la Vague is an essential purchase for connoisseurs of Godard and Truffaut, cinema and the movement that changed cinema. Recommended, if with serious reservations.

|