|

Maybe it's just me, but the very name Mabuse is as emotive of the sinister as that of Dracula, another three-syllable surname that you could never imagine your daughter adopting through marriage. If the name is new to you then I'm guessing you don't hail from Germany, where Norbert Jacques' novel Dr. Mabuse, der Spieler has apparently never been out of print, and since its publication in 1921 has spawned four further novels and 12 films, and there's a new one in production as I write. The first three were directed by visionary filmmaker Fritz Lang – the first was a two-part silent, the second a follow-up to his justly celebrated M, and the third was to prove his final feature as director. All are important and fascinating films in the own right, and while the first two have been released on UK DVD by Eureka as stand-alone discs, this marks the first UK DVD release of the third film in the series, Die 1000 Augens des Mabuse. All three films (four if you more accurately count Dr. Mabuse, der Spieler as the two separate features they were intended to be seen as) have been remastered and are blessed with new commentaries by David Kalat, author of the book The Strange Case of Dr. Mabuse: A Study of the Twelve Films and Five Novels.

With the transfers and special features different for each film, I've decided to cover the three discs in sequence, addressing the picture, sound and extras for each at the end of the review of the film in question.

There's a brief exchange late in the Part One of Fritz Lang's extraordinary silent crime drama Dr. Mabuse, der Spieler [Dr. Mabuse, the Gambler] that at first glance, particularly from a modern perspective, can't help but feel like a bit of an in-joke. At a party at the home of the wealthy Count Told, the film's title character and super-villain Dr. Mabuse is perusing a number of paintings hung on the walls when Told asks him, "How do you stand on expressionism doctor?" to which he replies dismissively, "Expressionism is just playing around." As those who know their film history will be aware, the Expressionist movement was a key influence on German cinema of the period, including the work of a certain Fritz Lang. But this was one film, apparently, that Lang did not want to be read as expressionistic, and the most famous example of expressionism in his oeuvre – the 1927 Metropolis – was still five years off. It's worth noting that the line was also in novel on which the film is based, but it still makes me smile.

If you've not got around to seeing Lang's 1922 Dr. Mabuse, der Spieler, then for once that tired old claim that you've never found the time to fit it in might just wash. In its present, restored version it runs for a whopping 270 minutes, that's four-and-a-half hours in old money. For an audience not enthusiastic for silent cinema, the prospect of sitting in front of a sound-free film for that length of time, one bereft of comedy and whose intra-titles are in German, will doubtless prompt a ream of excuses involving sudden household emergencies and alternative engagements. If that includes you then I've just two words for you: your loss. Although designed from the outset to be viewed as two separate films, I watched both in a single session and got so caught up in Part One that I hastily cancelled an evening out to avoid interrupting the experience midway. Yes, it really is that good.

As indicated by the title, Dr. Mabuse is a gambler, but not under his own name or face. A psychoanalyst of some renown, Mabuse is also a skilled hypnotist, a master of disguise and a ruthless criminal mastermind. And when he gambles he likes to win, to which end he employs mind control tricks to force his opponents to make mistakes and even fold when they have a winning hand.

A flavour of Mabuse's ambition and guile is captured in the opening five minutes, as a bag containing an important international trade contract (nicely revealed to us in through trick photography) is snatched from its courier and tossed from a moving train into the rear seat of a car below, and is then passed to the disguised Mabuse by a man in whose vehicle he has hitched a ride following a carefully stage-managed road accident. As the bag is recovered and delivered to its originally intended destination, its contents seemingly unmolested, another Mabuse operative uses the information contained within to successfully bleed the stock market.

The core element of Mabuse's gang is surprisingly small, but the suggestion is that he has operatives everywhere, sleeper cells to be called up for duty when the time is right, their loyalty ensured by teasingly unspecified methods. It's in this capacity that showgirl Cara Carozza is roped into the Doctor's latest scam, one that involves him working his powers on wealthy young Edgar Hull, whom he uses to gain admission to the exclusive 17 Plus 4 club, where he proceeds to fleece his young companion to such a degree that he has to settle for an IOU. Hull wakes from his trance with no memory of the fateful game or his heavily disguised companion, but soon learns that he owes a sizeable sum to someone named Hugo Balling at the Excelsior Hotel. When he visits the hotel, however, he finds the real Balling suffering from a spectacular hangover and with no knowledge either of Hull or his debt. A little relieved, Hull is on his way out when he's passed by the rather attractive Cara, who makes a point of dropping her glove on the way down to the lobby. Ever the gentleman, Hull chases after her to return it, and step two of Mabuse's plan is set in motion.

In pursuit of Mabuse without even knowing who he's looking for is state prosecutor Norbert von Wenk, a man whose surname will likely provoke a few quick double-takes, at least in its written form. If Mabuse is the film's Fantômas – and the Feuillade serials are an acknowledged influence here – then Wenk is its Inspector Juve. That he is more sympathetic than his predecessor is due less to his sparkle-free personality than the fact that the man he's up against really is a nasty piece of work. A humourless megalomaniac with Bond villain ambitions, Mabuse has none of the dark romantic allure of Fantômas or Irma Vep, and is so callous and self-interested that you end up siding with Wenk by default.

But as played with evil-eyed menace by Rudolf Klein-Rogge, Mabuse is a genuinely compelling creation and one of the all-time great movie bad guys. Indeed, it's his significant role in the unfolding drama that gives this first Mabuse film a real edge over its cinematic successors, where the good doctor is represented only by those looking to walk in his shoes. His immediate cronies are also a noteworthy bunch, consisting of effete and cocaine-addicted valet Spoerri, no-nonsense chauffeur and hard man Georg, perpetually nervous butler Fine, and a human bullfrog of a thug named Hawasch, a man of genuinely extraordinary facial features who is played by an actor whose various stage names include the frankly glorious Karl Huszar-Puffy.

There's certainly enough plot here to justify the running time and it bristles with memorable set-pieces, including a superb first encounter between Mabuse and Wenk – both in disguise and unaware of the other's true identity – in which Mabuse plants the Chinese words "Tsi-nan-fu" in Wenk's mind and prompts him to see them everywhere he looks. It's a nifty bit of trick photography that is developed to striking effect in a climactic car chase, as Wenk is drawn to his possible death by the name of the quarry he has been hypnotised by Mabuse to drive into, which appears on screen as animated text, seemingly beckoning the speeding car to its doom.

If the characters and storytelling provide the film with its primary pleasure then there are secondary thrills aplenty in the handling, particularly Lang's way with match edits, mid-scene location shifts, sequence cross-cutting and the above-mentioned effects work, which may look primitive by today's standards but must have startled audiences of the time. Scene after memorable scene makes its mark, including the above-mentioned encounter at the 17 Plus 4 club, Wenk's first meeting with the coolly observant Countess Dusy Todd, the vibrantly staged trip to The Petit Casino, the seemingly telepathic control Mabuse exercises over Count Todd, and an attempt to kill Wenk by planting a bomb in his office. It all builds to a superb final act involving a preposterous but impressively staged demonstration of mass hypnosis, a breathless car chase, a brilliantly handled police assault on Mabuse's hideout and a genuinely haunting finale.

Dr. Mabuse, der Spieler is one of those classic films about which much has been written, often with the emphasis on its technical and subtextual elements, the background to its production and its position in the oeuvre of such a celebrated auteur – indeed, you'll find just such an analysis in the commentary on this very disc. It's easy to be put off by this and the prospect of watching a film whose rewards appear to be intellectual rather than emotional, but it's worth remembering that the film was designed primarily as an entertainment, and this is something it delivers in noir-tinted spades. Ultimately, it's the combination of all of these elements – it's compelling characters and storytelling, the boldness of its technique, the layering of its social subtext – that give the film its extraordinary longevity and make it play so well even 87 years after it was first shown, and which qualify it as – and there's absolutely no pun intended here – the true godfather of movie crime thrillers.

The transfer here has been sourced from a reconstruction from two negatives and is the result of a cooperative effort between Berlin's Bundesarchiv-Filmarchiv, the Filmmuseum München and Friedrich-Wilhelm-Murnau-Stiftung. Full details are in the booklet accompanying the DVD, but safe to say this has been quite a task and the results do the work proud. Although some minor flicker remains, the contrast is consistently excellent and the level of sharpness, though variable, is at its best very impressive – the detail on faces and beards and the crisp sheen of the top hats in the stock market sequence are a fine example, as is the detail in Cara Carozza's object-packed dressing room. The quality drops a little in the effects shots, though this is understandable given that we're looking at multiple exposures. Grain is evident and some damage and dust remain, but this is the sort of transfer we could only have dreamed of seeing of a film of this age just a few years back.

The Dolby 2.0 stereo music track is very clear and with distinct separation of instruments. Whatever the percussion instrument is – I'm guessing a xylophone but I'm not musically experienced enough to be sure – it gets really loud at times.

Commentary

Film historian and author David Kalat has so much to say that he's able to talk about the film and its makers for the full four-and-a-half hours with barely a pause for breath. A huge amount of ground is covered, including the cuts made by censors for the UK and US releases, the differences between the film and Norbert Jacques' novel, Lang's influences and the impact this film had on later works, and the social background to the production and story development. Scenes and film techniques are examined, underlying meanings explored, characters analysed and the work of contributors discussed. The events that led to the film's production and the career of author Norbert Jacques are covered in some detail, and other writing on the film is referenced. Kalat takes issue with the idea that the film is in any way expressionistic and at one point commands that we do not call Lang an expressionist, an argument he cuts short before we can get to the director's later Metropolis, one of the true giants of German expressionist cinema. Obviously the commentary is spread over both discs with the film itself and is consistently fascinating stuff – even if you know the film well you're likely to find plenty to interest you here.

The rest of the extras are on disc 2.

The Music of Dr. Mabuse (12:57)

Composer Aljoscha Zimmermann provides a revealing and – particularly for us non-musicians – fascinating insight into his approach to the composition of the score for this release of the film, with emphasis on specific themes and sequences.

Norbert Jacques: The Literary Inventor of Dr. Mabuse (9:35)

Michael Farin, author of the second series of Mabuse radio plays, provides a brief but useful introduction to author Norbert Jacques, key elements of the first Dr. Mabuse novel, Lang's film version, and the subsequent spin-offs.

Mabuse's Motives (29:55)

An informative and analytical documentary, produced by Friedrich-Wilhelm-Murnau-Stiftung in 2004, that examines the film, its production, and its symbolism, motifs and meanings, as well as the social context in which it was made and should be viewed. That Lang was keen for the film not to be seen as expressionistic is reiterated here, and the development of some of film's key elements is traced from and to other film works. Includes some welcome extracts from an archive interview with Lang, which is in startlingly good shape, and brief snippets from Lang's 1919-20 serial The Spiders [Die Spinnen], from which some of the sequences in Mabuse were drawn.

Booklet

A typically fine MoC booklet containing notes on the restoration, a 1924 article entitled Kitsch: Sensation Culture and Film by Fritz Lang, a scrapbook of Fritz Lang comments on Dr. Mabuse, der Spieler, credits for the film, and some excellent quality production stills. What looks like the original cover of Norbert Jacques' novel is also used to front the booklet.

| Das Testament des Dr. Mabuse |

|

|

Das Testament des Dr. Mabuse [The Testament of Dr. Mabuse], Fritz Lang's follow-up to his marathon two-part silent crime drama Dr. Mabuse, der Spieler, kicks off in the manner of a full-blown Noir thriller, as the camera snakes through a boiler room to the sort of rhythmic industrial beat that would make David Lynch green with envy, then comes to rest on the figure of an armed man in hiding. With no introduction or set-up, we're plunged into a story that's been playing out for some time and is now close to its conclusion. The man is spotted by those from whom he is hiding but allowed to make his way out, where he comes under immediate attack and is seemingly killed in an explosion. A short while later, however, he's making an urgent phone call to Inspector Lohmann, his former employer, but before he can reveal the fruits of his dangerous unofficial investigation, the room is plunged into darkness and he is wildly firing at a figure we never see. When Lohmann arrives there's no trace of the man, only the remnants of a word scratched into the window glass...

It's an attention-grabbing opening for a film whose plot does not always unfold in traditional linear manner, with the backstory to the scene revealed in conversational retrospect, while Lohmann's subsequent investigation requires our full attention to follow in the sort of detail demanded by the film's dense plotting. The story that subsequently unfolds is as much a sequel to director Fritz Lang's previous film M as to his earlier Dr. Mabuse, der Spieler, sharing as it does M's chief investigating officer and some of its motifs and imagery – at the time of its release, Testament could almost have seemed like the second in a planned series of Berlin-based crime dramas based around Lohmann's office. But while the references to M are largely for cineastes to spot, the connections to the first Mabuse film are self evident from an early stage. But if you've not seen Dr. Mabuse, der Spieler for a while then don't worry, because respected psychiatric doctor Professor Baum is on hand to provide a brief recap to both us and his students of what happened to Mabuse and what he's been up to since.

With Mabuse seemingly confined to the funny farm, elsewhere in the city a criminal gang discuss a recent job, and there's dissent in the ranks from one Tom Kent, who is unhappy with the idea of taking lives to achieve their goals. This, of course puts him on a higher moral ground than his comrades and makes it safe for an audience to side with him despite his background. He's also involved with nice girl Lilli, who has no idea that he works for a criminal organisation of some size and power, one whose unidentified leader addresses his troops whilst hidden by a curtain, and woe betide and poor fool who tries to look behind it.

Initially, we seem to be in the realms of the supernatural, the suggestion being that the seemingly out-of-his-tree Mabuse is somehow telepathically running the city's most feared crime syndicate from the confines of his psychiatric cell. There's certainly something afoot here, evidenced in the accurate detail of recently committed and even upcoming crimes found in the doctor's intense scribbling, which is discovered by chance by a Dr. Kramm on a visit to Baum's office and is something he feels worthy of police attention. Unfortunately for him his intentions are overheard, and in an immaculately staged set-piece he is killed in his car before he can pass the information on.

But just when you're sold on the idea that Mabuse can indeed reach out beyond his confinement though the sheer power of his mind, he ups and dies. At this point it's anybody's guess where the plot will go next. Is Mabuse really dead or is this all a trick to return him to the criminal fold? Just what's got into Baum that he could excitedly pronounce Mabuse a genius rather than a madman? If the man behind the curtain isn't either of these two – and it's clearly suggested at one point that it can't be – then who is it? The supernatural element is upped a sizeable notch when Baum is visited and physically invaded by what appears to be Mabuse's ghost, his brain exposed and his eyes the size of an autopsy alien's, as disturbing an apparition as you'll find in any film of the period. Nothing is quite what it seems here, however, and by switching between the objective and the subjective, Lang keeps us guessing until he's ready to show his hand.

Lohmann, it has to be said, makes for a far more engaging and likeable investigator than the previous film's rather uptight von Wenk. A lot shrewder and more resourceful than his bulk and early bluff suggest, he also has a somewhat direct approach to criminal apprehension, at one point charging through gunfire that has kept half the police force at bay ("I've had enough of this!") to bring an armed siege to a speedy conclusion. It takes longer to engage with the indecisive Tom, but once he and Lilli are sealed in a room that they are forced to tear apart to locate a hidden bomb – a brilliantly staged and thrillingly cross-cut sequence that is allowed to play out at nail-chewing length – we're with him all the way.

With its shorter running time, The Testament of Dr. Mabuse is inevitably not quite as packed with plot and incident than its four-and-a-half-hour predecessor. But Lang still gives it his best shot, compressing what feels like a good three hours of narrative and character interplay into a fat-free two, the filmmaking economy on display here a model for noir thrillers to come. As with its predecessor, it builds to a memorable climax, one involving a real-life factory destruction and a car chase whose breathless pace and cutting survives the visible back-projection and odd bit of speeded-up motion. Adding to an already rich brew is a subtextual element that is open to multiple interpretations, but the image of a ranting megalomaniac with ambitions for world domination and Mabuse's frantic in-cell book writing make the allusions to the rise of Hitler and the then incumbent Nazi party hard to ignore. This may also have contributed to the film being banned in it's native land until 1951, and even then only released in a shortened 111 minute version. Lang later claimed that he was summoned to the office of propaganda minister Joseph Goebbels, where the reasons for the ban were explained and he was offered the job of production supervisor at UFA studios. He chose instead to flee the country and the role fell instead to Leni Riefenstahl, who two years later made Triumph of the Will, an astonishing technical achievement whose glorification of Hitler and the Nazi party would haunt her for the rest of her life.

With the briefer running time and Mabuse's presence reduced to a few short but memorable scenes, Testament may not be quite as groundbreaking as its predecessor, but it's not far short. It tells a compelling and intricately developed story in a bold and arresting manner, features editing and camera techniques that were ahead of their time, and makes strikingly creative use of sound, particularly impressive when you remember that this was only Lang's second non-silent feature. We tend to think of the Noir thriller as a largely American phenomenon – certainly it's in Hollywood that it really thrived – but if you're searching for evidence of the genre's Germanic cinematic roots, then you need look no further than The Testament of Dr. Mabuse.

If you thought the picture quality on Dr. Mabuse, der Spieler was impressive then prepare to have your eyes widened by the sharpness and level of visible detail on the transfer here. The contrast is bold without sacrificing shadow information and the image boasts a sometimes rich tonal range that adds texture to the sets and backgrounds and really showcases Emil Hasler and Karl Vollbrecht's emotive art direction and Karl Vash and Fritz Arno Wagner's gorgeous lighting camerawork. A slight flicker and the odd small bit of damage remain, but dust spots are very rare. An excellent job for a film of this age.

The mono soundtrack is inevitably restricted to a narrow dynamic and tonal range and some hiss and even crackle can be heard throughout, but dialogue is always clear and the rest is pretty much par for the course – certainly there are no alarming damage-induced pops to contend with.

Commentary

Once again we have film scholar and author David Kalat to take us through the film and the background to its production in enthralling detail. Areas covered, often in some depth, include the film's political commentary and how this has been interpreted, Goebbels' reported objections to it, the changes made to the novel, the boldness of specific film techniques, the truth behind Lang's flight from Germany, and the work of some of his key collaborators on the film. Occasionally Kalat finds meaning in elements that I can't help suspecting were never designed to be read this way (something the films of all proclaimed auteurs eventually fall victim to), though he does credit this film with having expressionist elements, which surprised the hell out of me after his remarks on the previous commentary. The various cuts of the film are explored at some length, particularly in the way they changed how scenes and characters would be read by audiences, and in a rare but welcome divergence from the normal spoken commentary, an alternative main theme score and audio clips of the American dub are played to illustrate points being made. Once again, an essential companion to the film.

Booklet

Another classily produced booklet that includes in its contents the original German programme for the film, a detailed 1982 essay by Michel Chion, a scrapbook of Fritz Lang comments of the film (and the nature of God), film credits and production stills. The original German poster is used for the cover.

Die 1000 Augens des Mabuse |

|

|

Coming to 1000 Augens des Mabuse [The 1000 Eyes of Dr. Mabuse] so quickly after the two previous films can provide a small jolt, with the wider aspect ratio, brighter imagery and jazzier main theme feeling a little out of step from its darker predecessors. There's also no sign of Mabuse himself – he is confirmed dead and his criminal empire outlined in a board room meeting held under a dense smog of cigarette smoke – and thus no question that we're dealing with his legacy rather than the man himself. And however impressive his successors may be, there really is only one Dr. Mabuse.

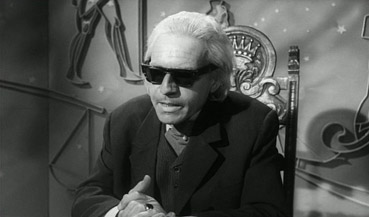

As with its predecessor, the question of just who has stepped into Mabuse's shoes is initially unclear and remains that way for a good part of the film, though there are certainly plenty of potential suspects. There's wealthy American businessman Henry Travers, who's in town to buy out the Taran nuclear works and who talks a woman named Marion out of her suicide bid when she chooses the ledge outside his hotel room to jump from. There's cheery insurance salesman Hieronymus B. Mistelzweig, who seems to be on the level but is prone to sudden serious glances at others when their backs are turned. And what about Marion's psychiatrist, Professor Jordan, whose arrival to deal with Marion's distress feels a little too perfectly timed? (We'd instantly suspect him nowadays because he has a beard.) Then there's hotel detective Berg, who we probably wouldn't be considering at all were he not in a position of power at the Luxor Hotel, which by the time we meet him has already been identified as a potential hub for criminal activity. You might also wonder about the undisclosed idenity of the club-footed individual who's keeping a close watch on the guests with hidden video cameras.

And what of blind, white-haired clairvoyant Peter Cornelius? He's not staying at the hotel but has an uncanny way with crime prediction. We get to meet him when he calls sceptical police commissioner Kras (played by the splendid Gert Frobe and a direct replacement for the previous film's Inspector Lohmann, to whom he bears more than a passing physical resemblance) after one of his visions predicts what looks like a murder. The sceptical Kras is initially dismissive, but when TV reporter Peter Barker is found dead in his car at the predicted location, he starts to take notice. A heart attack is initially diagnosed but we know better, having witnessed his assassination from a nearby car at the start of the film. Further investigation reveals he was killed by a needle fired into his brain from a powerful air gun, the blueprints for which were stolen from the American government and found in the post-mortem search of Barter's flat. A link is made to a number of murdered industrialists – care to guess which hotel they all stayed at when in town? As Travers tries to get to the root of Marion's suicide bid and Mistelzweig alternates between cheery introductions and suspicious glares, Kras begins making his own enquiries at the hotel, unaware that he's not the only one conducting an investigation there.

Despite the opening murder – which with a few small changes is effectively a retread of a similar scene from Testament – 1000 Eyes feels lighter in tone than its predecessor, though this has more to do with its look and feel than its content. It was released in 1960 and looks very much a film of its time, something as visible in its camerawork and lighting as its set design and costumes, though this certainly plays its part – the spectacled assassin who kills Barter is very much a man of his time and would not have looked out of place a few years later in the likes of Bullitt or Point Blank. But there's still enough intrigue and story complexity for the film to sit comfortably alongside its predecessors – in terms of their role in the narrative, almost no-one is quite who they appear to be and there's plenty of effective misdirection to keep you guessing.

The law of diminishing returns leaves 1000 Eyes the least innovative of Lang's three Mabuse films, but it's still an engrossing and complex crime thriller with its share of surprises and memorable scenes. The early in-car assassination may be recycled from Testament (the bombing of Kras's office is also a revamp of a key scene from Dr. Mabuse, der Spieler), but it's still a smartly staged and tone-defining set-piece, while Lang's use of cross-cutting, mid-sentence scene switches and associative sound is as rewarding as ever. The title also hints at a subtext whose potency has actually increased with the passing of time, as the hotel guests are voyeuristically observed on a close-circuit television system by unseen eyes, while a two-way mirror offers one of the watched the opportunity for some role reversal, a suggestion he is initially outraged by but is unable to resist. In the age of Big Brother and in a society that now has the largest number of CCTV cameras per capita in the world, this can't help but feel like Cornelius's most accurate prophecy of things to come.

As mentioned above, it's a bit of a jolt after six-and-a-half hours of academy framed Mabuse to have the picture switch to anamorphic widescreen and have the previous noir imagery transformed into a more recognisably late 50s/early 60s aesthetic. But once again this is a first-class transfer, a sharp, almost blemish-free picture with solid contrast and deep blacks that occasionally swallow up the shadow detail a little.

Both the German and English language tracks are included here. The German track is louder and slightly clearer, but at the expense of some background hiss that's less audible on the English track. As ever, it's interesting to watch the film with the English language track playing and the English subtitle translation of the German enabled to spot the differences, my favourite being the switch of Hieronymus Mistelzweig's middle initial from B ("for Belly") on the German track to P ("for Paunch") on the English. As Kalat points out in the commentary, the international cast means that both tracks are actually dubs, but as a sizeable portion of the cast are German speakers, the German track the most authentic. That said, the English dub is far better matched to mouth movements than most.

Commentary

And once again we have David Kalat to take us through the film and its production and to offer some intriguing readings of its themes and motifs. As ever, there's a wealth of background information provided, but less of it is screen specific than on previous commentaries in the set. Discussions instead focus on the careers of the key actors, the reasons for completion insurance, the multinational cast and the use of dubbing, the proposed but unrealised dual language shoot, and an off-topic story about Goldfinger that leads on to Kalat defending his previously expressed views on actor Gert Frobe and his wartime connections with the Nazi party. A sizeable chunk of the second half of the commentary is taken up by three possible explanations for Lang's return to Mabuse after such a long break, all of them well worth a listen.

Alternate Ending (1:03)

The ending that appeared only on French prints of the film – the change is small in terms of screen time, but enormously significant to the conclusion.

Wolfgang Preiss Interview (15:11)

An interview conducted with Wolfgang Preiss, an actor who became so associated with the later Mabuse films that he was even included in the promotional material for one that he was not actually in. Conducted in November of 2002, just weeks before Preiss passed away, it's both important as a cultural document and a consistently engaging chat, particularly in his memories of his early career, of landing the role (it's best not to know which one until after you've seen the film; if you've not seen it then make an effort of avoid the IMDb cast list), of Lang's directing style and of working outside of Germany – on being offered the role of a Nazi officer in The Train and Von Ryan's Express, he responds that you just can't say no when Burt Lancaster or Frank Sinatra has the lead role.

Booklet

Another first-class booklet featuring a brief piece on Fritz Lang's chimpanzee Peter by David Cairns (yes, you read that right), a scrapbook of Lang's comments on the film, on contemporary cinema and on working with Jean-Luc Godard on Les Mepris, a brief extract from Lotte Eisner's book on Lang on his unrealised projects, credits, production stills and even a Japanese poster. The German poster is used for the cover.

As box sets go, this is a doozy, eight hours of thrilling and painstakingly restored film entertainment, a further eight hours of densely informative commentary, well over an hour of stand-alone DVD extras, and three booklets. Individually I'd be enthusiastically recommending each one, but as a box set they're an absolute treat. Very highly recommended.

|