|

There are, it has to be said, some surprising disadvantages to making a truly great film, the principal one being that all of your subsequent work tends to be directly compared to it and will often take a critical pounding if it doesn't measure up. Few suffered more from this than Orson Welles, who had the temerity to make Citizen Kane, a widely acknowledged masterpiece of American cinema, at the absurdly young age of 26. A grand filmmaking career clearly lay ahead, but until comparatively recently, every subsequent Welles project languished in the shadow of that astonishing debut. There's almost a sense of critical outrage when a filmmaker fails to deliver a second or third masterpiece, or dares to go off and make a film that puts entertaining a mainstream audience over personal, political or social statements.

Now before I start to sound like one of those writers who try to distance themselves from "the critics" even as they are writing as one, I should admit that I'm as guilty of this as anyone and will happily argue my case, albeit from the soapbox of personal preference. I'm sure, for example, that I'm not the only one who let out a small groan when they discovered that the recent historical idiot comedy Your Highness was directed by none other than David Gordon Green, the man who at the age of 24 gave us the thoughtful and tenderly observed George Washington and who The Guardian's Peter Bradshaw once claimed was "set to become a Terrence Malick for the 21st century."

Of course, when you create more than one masterpiece on the trot then the problem is multiplied. Such was certainly the case with German maestro Fritz Lang, who in the space of just eleven years directed Dr. Mabuse, der Spieler, Metropolis, Spione, M and Das Testament des Dr. Mabuse, acknowledged cinematic giants all. Like a number of his country's prominent filmmakers, he fled to Hollywood during the Nazi years, where he made a number of prominent and greatly admired films, but nothing to quite equal the legendary works for which he is still primarily remembered. Then, in what proved to be the twilight of his career, he was lured back to Germany to embark on a project he had nurtured since his early days, one based on a novel by his ex-wife and once regular collaborator Thea von Harbou. So, a return to the futuristic and expressionist joys of Metropolis, then, or a work as complex and multi-layered as the first Das Testament des Dr. Mabuse or M? Well, not quite. The resulting duo of films – Der Tiger von Eschnapur [The Tiger of Eschnapur] and Das indische Grabmal [The Indian Tomb] – became known as Lang's Indian Epic and were designed from the start to be mainstream crowd pleasers, exotic adventure stories set in a picture-book version of a far-off land. They delighted the public but took a critical hammering, and although television re-runs have kept them popular on home turf, elsewhere they have all but dropped off the critical radar. It's unlikely you'll have seen them and there's even a good chance that Eureka's press release was the first time you'll even have heard of them. It certainly was for me. I'd even venture suggest that if you were sat down in front of them with no prior knowledge, precious few of you would guess that they were directed by Lang at all.

Although it echoes the two-part structure and combined running time of the 1921 silent version of the story directed by Joe May (which Lang wrote with von Harbou and was originally slated to direct), it seems likely that decision to spread the story over two films was made in the belief that, in 1959 at least, the prospect of a three-an-a-half hour adventure story would be off-putting for the very audience at which it was targeted. It's the same thinking that saw the second half of Richard Lester's splendid 1973 Dumas adaptation break off to become The Four Musketeers and has recently seen the latest Harry Potter opus cleaved into two. Of course, a cynical observer might suggest that by releasing one film as two, the studio can potentially double its return on a single production budget, and if the first part is successful then the second is pretty much guaranteed to find an audience of similar size.

The Indian Epic kicks off with The Tiger of Eschnapur, and anyone who grew up watching British or American films in which white adventurers find themselves at odds with the natives on foreign shores will quickly find themselves on familiar turf here. The ostensible hero is German architect Harald Berger, who has come to India to build a new temple for wealthy and powerful Maharaja Chandra. In the process he meets a beautiful dancer named Seetha, whom he saves when a tiger attacks her wagon, an act of bravery that earns him the Maharaja's friendship. Harald and Seetha subsequently fall for each other, which is unfortunate given that Chandra is also in love with Seetha and plans to marry her.

Let's get one thing straight: despite its vivid location footage, this is no documentary portrait of late 50s India but one constructed largely from the filmmakers' colourful imagination. Key Indian roles are played by European actors in dark skin make-up, which although feels a little peculiar now was a common enough practice in days gone by, particularly if you wanted your cast to speak German, not a language common to late 50s India (let's not forget that as recently as 1984, the very English Alec Guinness was similarly transformed for David Lean's A Passage to India). Both films share with their English-speaking contemporaries a very western view of a stranger in a strange land, one in which the ways of the natives are portrayed as quaint, peculiar, or more primitive and barbaric than our own. Cultures in such films invariably clash, and rarely did the visitors and their hosts learn to co-exist in peaceful harmony. Then again, that's probably because, like so many Brits and Americans abroad, the interlopers refused to adapt to the country they were visiting and instead all but demanded that tit adapt to them, and were quick to react if it declined to do so.

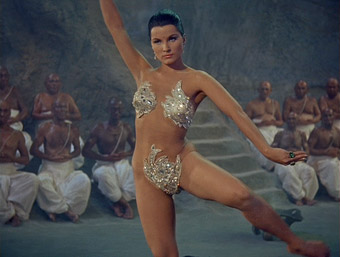

In some ways, Harald's romance with Indian dancer Seetha can be seen as progressive, at least for 1959, when mixed-race relationships were still frowned upon by western society and was certainly not seen as the stuff of mainstream cinema. But as played by Colorado born Debra Paget, the exotic Seetha is no more Indian than her Caucasian male co-star – the result, we are told, of a union between an Indian mother and Irish father. In his splendid commentary track on this very disc, David Kalat intriguingly suggests that this allows the interracial romance to also be read in a more negative light, as the story of a good-looking white man saving this light skinned half-European girl from marriage to – oh, the horror – a dark skinned Indian tyrant.

All of which suggests a level of subtextual complexity that I seriously doubt was ever intended. Auteur status is rarely earned on a filmmaker's ability to spin a good yarn, but go looking for Lang-specific elements here and you could end up on a 202 minute metaphor hunt, and risk setting yourself up for accusations of ascribing false meaning to scenes based purely on the fact that Lang was the director. Indeed, the general opinion is that The Indian Epic is primarily just what it purports to be, a story of love battling difficult odds dressed in the comfortably fitting overcoat of an exotic adventure. And on this score it fares pretty damned well. If you accept that blacking up Caucasian actors and the occasional fake tiger were conventions of the time, and that the almost comically false snake that the dancing Seetha has to hypnotise is no more unreal than the python Kaa in Zoltan Korda's widely respected 1942 adaptation of Kipling's The Jungle Book (whose visual style and colour palette Lang's films vividly recapture), you should have a blast. The story moves at the sort of no-nonsense lick that that was once standard operating procedure for such cinematic fare and the first film even ends on a cliffhanger and a textual invitation to see how the situation will be resolved.

With the setup complete and the characters established, The Indian Tomb kicks off at an exhilarating gallop and rarely lets up, propelling the story along a path littered with incident and confrontation, and allowing two of the minor characters from Part One – Berger's sister Irene and her irritable husband Walter – to move to centre stage as they investigate the circumstances of Harald's disappearance. As played by Swiss actor Paul Hubschmid (who as Paul Christian later played the lead in Eugène Lourié's cult favourite The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms), Herr Berger is an efficient if uncharismatic leading man who shows little respect for the culture he is disrupting and who, in a manner typical of a male westerner abroad, refuses to do what he is told even when common sense dictates that he should. He works well enough with his female co-star, and while a genuine Indian actress would have given their romance more bite, Paget is alluring and even erotic enough to make her a convincing object of Chandra's desire. Chandra himself is enjoyably played by Austrian actor Walter Reyer, who despite his bad guy status (a little unfair when you consider that it's he who is the wronged party here), invests his character with enough humanity for us to take his side when his treacherous brother Prince Ramigani plots to depose him. Claus Holm's animated agitation as Walter is nicely tempered by Sabine Bethmann's calmer Irene, while possibly the most convincingly Indian of the Caucasian cast is Jochen Blume, who as engineer Asagara underplays his role nicely and is far and away the most sympathetic of would-be locals.

But having pricked Lang's auteurist bubble above, I do feel the need to re-inflate it a little, as while it's hard to make a case for The Indian Epic as quintessential or even typical Lang, it still steps outside the adventure story norm often enough to mark it as the work of a filmmaker of particular and occasionally audacious vision. Momorable examples include Seetha praying to a goddess for help and a spider responding by spinning a concealing web at a speed that suggests it has bionic implants, or the extraordinary sequence involving Seetha's erotic snake dance, which despite her strategically placed jewelled attire is effectively performed in the nude. Against early expectations, there is real tension at times, as when Seetha's terrified servant is forced to participate in a potentially lethal sword-through-the-basket trick, or when a James Bond-dressed Harald is chased into the tiger's arena and given only a spear to defend himself with. Elsewhere, it's the quieter moments that register, as in the strangely compelling sequence in which an overheated Irene expresses her irritation at the squeaking and watchful nature of the servant-operated ceiling fan. Perhaps most memorable of all for this modern horror fan is the startling image of an imprisoned leper army that stands creepily motionless before the frightened Irene and then advances on her like a posse of extras from Night of the Living Dead, a genre-changing film that was still nine years away.

But in the end, what makes The Tiger of Eschnapur and (especially) The Indian Tomb really worthwhile are the more traditional skills of good storytelling and lush presentation, and here Lang is admirably served by Helmut Nentwig and Willy Schatz's striking art direction, Günter Brosda and Claudia Hahne-Herberg's eye-catching costumes, and Richard Angst's sumptuous cinematography, which ignores naturalism in favour of the sort of rich colour imagery that you could only achieve by flooding even supposedly dark locations with light. And in spite of its almost archaic quaintness and its fantasy India, The Indian Epic a consistently enjoyable yarn that fully justifies both its two-part structure and its three hour twenty minute length. It's unpretentious old-school romantic escapism, which evidence suggests is exactly what Lang intended it should be.

Now here's a tricky one. In many ways this is a glorious transfer: the colours are rich and vibrant, the contrast gorgeous, and the sharpness level of detail exceptional for a DVD image. For a film first released back in 1959, it's a remarkable restoration, one that really showcases the cinematography and set design, and at times seems to genuinely leap from the screen. There is, however, one small caveat, and that lies with the use of some visible digital enhancement, which although does bring out the fine detail in the sets and costumes, also grabs the film grain and turns it into a dancing pattern that, on a large screen at least, is visible on just about every light-coloured surface, including skies, clothing and undecorated walls [I have since learned that this may be a side effect of the colour process used by the film, one that current high definition masters have made more visible]. The restoration also appears to have sidestepped the cross-dissolves, which often have a slightly different colour palette to the scenes they bookend and are even slightly out of register with them, providing a small visual pop on their completion. This was, I should point out, once quite common on transfers of films made at a time when dissolves were effectively effects shots created by a photochemical process – try to catch an older print of a colour film from the period on TV and chances are you'll witness a similar thing there. Frankly, though, I'd live with it, as the considerable virtues of this otherwise lovely transfer greatly outweigh these irritations.

The German mono 2.0 soundtrack more readily displays its age due to its narrowed dynamic range and some audible background crackle on the quieter scenes, but in other respects it stands up well, with the distortion-free reproduction of the music and no painful pops or other damage.

The English dub is also included, and on the commentary track, David Kalat makes a case for its legitimacy on the basis that both this and the German track were post-dubbed. But the German track does tend to synchronise with the performance, whereas the English track is as disconnected from the actors mouths as a dubbed Hong Kong-made martial arts film, only better performed. Curiously, there's also a slight echo to the English track, suggesting it was recorded in a large room rather than a sound studio.

Commentary

As someone who far prefers filmmaker commentaries to those delivered by scholarly experts, I'm always prepared to make a considerable exception for Masters of Cinema's human Fritz Lang database, David Kalat, who provided such enthralling commentaries on their DVD release of the Dr. Mabuse films and the recent restoration of Metropolis. Once again he delivers the goods, providing an almost pause-free commentary for both films that is crammed with enthralling information, entertaining anecdotes and intriguing readings of scenes and the films themselves. Areas discussed – and there are many – include the background to the production (this is covered in considerable detail), the influences of earlier works including Lang's own films, the changes made to the source novel, the Indian locations, the initial critical reaction, the cultural elements, and lots, lots more. Even if you don't warm to the films themselves (and you really should), for anyone interested in Lang's work and career, this is reason enough alone to buy this set.

French Trailers for both films (3:18 and 3:34)

Despite the presence of dust spots and a couple of jumps, both trailers are in good shape and a little less enhanced than the main feature.

Documentary (21:01)

Produced in Germany in 2005, this straight-laced look at the genesis and production of the films covers some of the same ground as the commentary, but really scores in the first-hand recollections of producer Artur Brauner, actress Sabine Bethmann, prop man Willi Schwandt, and Eva Ebner, who was hired as assistant director but lost the job when she was struck down with appendicitis. All of them personalise the production and have plenty of stories that are unique to this extra.

8mm Footage (3:01)

Shot by Sabine Bethmann in late 1958, the footage here is silent, dusty and brief, but is still an invaluable peek at the cast and crew on location in India. Includes a few shots of Lang at work.

Booklet

One of the things we always look forward to here are the booklets that accompany all Masters of Cinema releases. This one is well up to their usual standard, with a detailed essay on the film and it's production by Tom Gunning, Lang's own reflections on the experience of making the films, testimonials by actor Paul Hubshmid, cinematographer Richard Angst and art director Helmut Nentwig, extracts from critical reviews, a brief production history, and credits, stills and posters for both films.

Two films that are unlikely to change your perception of cinema or be used to demonstrate just why Lang is regarded as one of the most important and visionary filmmakers of the twentieth century, but as a two-part, old school exotic adventure they have plenty going for them, and there are enough stand-out scenes to fully justify their current rediscovery as a Fritz Lang film. Enhancement issues aside, the transfer sparkles, the commentaries are excellent, and the other sundry extras give the set a nicely completist feel. Warmly recommended.

|