| |

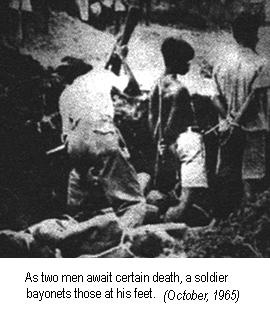

"The murder campaign became so brazen in parts of rural East Java that Moslem bands placed the heads of victims on poles and paraded them through villages. The killings have been on such a scale that the disposal of the corpses has created a serious sanitation problem in East Java and Northern Sumatra, where the humid air bears the reek of decaying flesh. Travellers from these areas tell of small rivers and streams that have been literally clogged with bodies; river transportation has at places been seriously impeded." |

| |

Time magazine, 17 December, 1965 |

After creating a considerable stir on the festival circuit and garnering gushing reviews, Joshua Oppenheimer's darkly beautiful, deeply disturbing docudrama The Act of Killing will be touring selected U.K. cinemas over the coming weeks. Two different versions of this remarkable film will be screening: a two-and-a-half hour-long director's cut, and a shortened print with a running time of 115 minutes. We recommend the director's cut to those of our readers for whom that is an option. It is worth the wait in order to experience the full emotional force of a unique, unmissable and unorthodox film that will linger long in the memory. The Act of Killing brilliantly does what documentary does best: it asks uncomfortable questions about our world. It also does what the best documentaries do: it raises troubling questions about itself.

Besides being one the most daringly original, powerful and frustrating films of recent years, Oppenheimer's troubling tour de force sits among that rare category of film that can be said to have changed the world. It revolves around a few of the mass-murderers behind the Indonesian massacres of 1965-66 – the bloodbath that exterminated the Indonesian Communist Party (the PKI), claimed over a million lives, ended the rule of Indonesia's founding president, Ahmed Sukarno, and ushered in the thirty-year dictatorship of General Suharto. Oppenheimer has helped lift the lid on almost half a century of silence, emboldened Indonesians to speak out about the darkest episode in their country's history, and focused the attention of Western audiences on a pivotal moment in the Cold War.

For reasons that will become clear, Oppenheimer withholds the details of the systematic slaughter that began after a failed military coup provided the pretext for a wave of anti-communist pogroms. It seems useful, therefore, to begin with a few facts. In 1965, Indonesia was the sixth most populous country in the world. It is now the fourth most populous. Before 1965 the PKI was the third largest communist party in the world. It successfully contested elections, had a membership of three million, and the support of 20 million Indonesians – in the co-operative and women's movements, in field and factory, in trade unions and universities, even in the armed forces. The party and its members were eradicated by the massacres, which targeted known communists but intensified, as mass hysteria took hold, to engulf Chinese immigrants as well as politically non-aligned intellectuals, peasants and workers. A CIA study of Indonesia described the anti-PKI massacres as "one of the worst mass murders of the 20th century."

For good and ill, Oppenheimer isn't much interested in such facts. This will delight some and discomfort others. When I declare an interest in information, he says: "If people only have time for two and a half hours for the Indonesian genocide, and if they don't get their primer or précis in my film, there's something wrong with the economy of our attention." He has a point, even if, surely, it's not an either/or matter. The question of whether or not Oppenheimer could have been found space to provide some historical and political context is but one of many matters this fascinating film invites audiences to consider. The director's cut of The Act of Killing challenges contemporary concentration spans as well as pain thresholds and, in so doing, provides an immersive cinematic experience that grants thought and feeling the time and space to flourish.

Oppenheimer's methodology is as unsettling as his subject matter. He calls his film, "a documentary of the imagination," and says; "It is a human story not a film about Indonesia." The Act of Killing probes the imagination and psychology of a group of ageing killers, who he films as they reenact their crimes and reminisce about their "glorious past" – the good old days when they maimed and murdered, with impunity and without conscience. In his film The Gatekeepers (2012) Droh Moreh talks to six forthright former heads of Shin Bet; in their Arab Spring portmanteau film The Good, The Bad and the Politician (2011) Ayten Amin, Tamer Ezzat and Amr Salamar interview a few of the baltagiya – Hosni Mubarak's hired thugs; in The Act of Killing Oppenheimer goes one step further, taking us into the very minds and rotten souls of the mass-murders he moved among for several years. He doesn't so much take us behind the mask of power as rip it off to reveal the heart of darkness beneath. In order to do so, Oppenheimer takes the blurring of the lines between fiction and reality to unprecedented, perhaps dangerous, certainly disturbing levels. As we watch the reenactment of a village being burnt down or a reenacted interrogation scene we sense the actors' tears are real and detect a whiff of the scent of the fear Indonesians have been living with for decades.

More than any film of recent times, The Act of Killing focuses our attention on what critic John Corner called a "crisis of confidence in the conventions of documentary." Speaking of his admiration for Jean Rouche, the founder of cinéma verite, Oppenenheimer says: "Rouche was allowing people to stage themselves, filming people mute then allowing them to dub on their own dialogue, just as I was doing in The Act of Killing. New technology and reality TV makes new things possible" Like Sight & Sound's Tony Ryans, I was left wondering what Rouche would have made of Oppenheimer's decision to leap from cinéma verite reportage to surreal colour-saturated images of robed women and killers gyrating in formation against a rural, waterfall-flecked backdrop or of go-go dancers shimmying beside a lakeside fast food restaurant in the shape of a giant fish.

That visually arresting fish observes the world before it with mournful eyes, seemingly aghast at human folly, saddened and shocked by what it sees. As we watch The Act of Killing we feel we know how it feels. The eerily ethereal, horror-tinged atmosphere evoked by such images call to mind the dreamscapes of Apichatpong Weerasethakul's Uncle Boonmee Who Can Recall His Past Lives (2010), and of his Mysterious Objects at Noon (2000) – which Oppenheimer cites as a key influence on his film. He says: "Apichipong gives people space to make things up." There is much making up of things, and much make-up, in The Act of Killing. It comes as no surprise, therefore, to learn that Oppenheimer is in enthralled by theatre, particularly the work of Brazilian director Augusto Boal.

Boal's groundbreaking 'Theatre of the Oppressed' projects attempted to democratize theatre by breaking down the space between stage and passive audience. He encouraged audiences to interrupt performances by show of hand, take to the stage, then re-imagine and reenact scenes in different ways. Oppenheimer says: "I got a gap-year grant to work with Boal in Brazil. He was running for parliament so that didn't happen, but he put me in touch with people in India who were using his techniques. They were very boring, but it was a formative experience. It got me thinking about how performance could come off the stage and intervene in everyday life. I was interested in how performance theatre provided a re-imagining of everyday life and how, in so many of our social rituals – from marriage to the parliamentary process – the construction of identities is inherently performative. The Act of Killing emerged from that interest."

© Martin Gray

Oppenheimer's emphasis on performance and reenactment, on individual not collective memory, leads inexorably away from fact. Those who attended the film's sold-out, first night screening at The Ritzy on Friday evening, particularly those discomforted by its lack of context, must have been grateful that journalist John Pilger was on hand for the Q&A, to fill in the gaps and flesh out Oppenheimer's ever-ready, always eloquent answers. Not that Joshua Oppenheimer is an ignoramus where Indonesia is concerned. Far from it: he has travelled there, on and off, since 2001, when he began working with local trade unionists for the campaigning video The Globalisation Tapes (2003)*. He learned the local language. He lived there for extended periods throughout the seven years it took to complete The Act of Killing. There's no doubting his commitment and probity. No more that of John Pilger, who has reported on the Suharto dictatorship down decades and written extensively on the 1975 Indonesian invasion of East Timor (which lead to the deaths of up to 300,000 East Timorese, a third of the population). Oppenheimer acknowledges a debt to Pilger's film on Indonesia, New Rulers of the World (2001)**, which, he says, "was very important to me as I tried to understand the situation." Oppenheimer and Pilger must have been the perfect pairing.

It is worrying that we hear so little about such a staggeringly populous country and its history. Although, for obvious reasons, films on Vietnam are plentiful, Peter Weir's The Year of Living Dangerously (1982) is, to my knowledge, the only fiction feature set during the massacres. We need effective investigative journalism and, particularly when that is in such short supply, we need fearless documentaries like Oppenheimer's, and like John Pilger's New Rulers of the World (2001) – which highlights the complicity of the British and U.S. governments in the 1965-66 massacres, and places those events in the context of the Cold War and Washington's 'domino theory'. Not for nothing did Thomas Jefferson say: "I tremble for my country when I remember that god is just." Pilger points out that the CIA supplied the Indonesian military with a 'hit list' of several thousand names, which were ticked off at the U.S. Embassy as 'commies' were killed or captured. He also notes that the massacres cleared the way for Western companies, which swiftly swooped upon what Nixon called the 'greatest prize' in Southeast Asia. 70 million Indonesians currently live in poverty.

The Act of Killing was co-produced by Werner Herzog and Errol Morris. It is easy to see why they were drawn to the film; they both believe that documentary arrives at profound, poetic truth only be means of fabrication, stylisation and imagination. Morris says of Oppenheimer's film: "(It) demands another way of looking at reality. It is like a hall of mirrors – the so-called mise-en-abyme – where real people become characters in a movie, then jump back into reality again." The 'real people' at the centre of The Act of Killing are vicious veterans of the right-wing death squads who murdered for pleasure and pay in 1965. The 'movie' in question is the cod film-within-a-film that Oppenheimer shoots with the boastful perpetrators. "god hates communists," one killer says, "that's why he made this film so beautiful." In that tawdry secondary film the killers make up, dress up, and cross-dress (pretty in pink) for their parts, as if starring in one of the Hollywood films they adore. This jarring juxtaposition of camp and horror, carnage and kitsch makes for disturbing but riveting viewing.

The cinephilia of these génocidaires follows the familiar patterns established by neo-colonialism the world over. They love popular American films, they sing Country & Western songs, they dress in cowboy boots and hats. They could well be Mississippi rednecks. They count Marlon Brando, Elvis Presley, Victor Mature, and John Wayne among their heroes. Disconcertingly, they're most fond of The Godfather and the films of D.W. Griffiths. Astonishingly, much of their unhinged anti-communism arose from the PKI's policy of banning American films. These violent small-time criminals controlled the black market in cinema tickets in the sixities, scapling tickets much as they now extort money from Chinese market traders. After evenings spent in the local fleapit, they would dance merrily across the road to their 'office' and emulate the screen gangsters they admired, while killing to their hearts' content. The dehumanization of their victims was total, a process all too depressingly common in history.

There is a third film-within-a-film in The Act of Killing. We watch excerpts from a three-and-a-half hour long state propaganda film, catchily titled: The Treachery of the September 30th Movement of the Indonesian Communist Party. This garishly violent film was part of the incoming Suharto regime's concerted campaign to stigmatize the PKI and legitimize its own autocratic rule. Like McDonalds and Coca Cola, the military junta understood the importance of capturing minds as they formed. Until recently this piece of political conditioning was compulsory viewing for all Indonesian school children. Its role in distorting the political consciousness of a people has been significant. Like Washington, Jakarta understood the efficacy of nurturing and unleashing anti-communist hatred. The unrepentant braggarts at the heart of Oppenheimer's film had been schooled to believe they acted heroically and righteously as they killed. This is the manipulation of populism by elitism to which the late, lamented Christopher Hitchins referred when he wrote: "The 'Church and King' mobs of Georgian England were outlets for energy that might otherwise have been directed at Church and King."

The film focuses on one of those who believed he acted with god and right on his side: a lithe, narcissistic charmer called Anwar Congo – whose surname chillingly recalls the Belgium genocide in that benighted African country, and one particular phrase from Joseph Conrad's Congo classic The Heart of Darkness: "Exterminate all the brutes." Actually, Anwar is less like a character from Conrad and more like amoral gangster Tony Montana in De Palma's Scarface (1983). "I kill a commie for fun." Anwar, who prides himself on his resemblance to Sydney Poitier, is as eager to appear in front Oppenheimer's camera as the director is to accommodate him. The film was shot, he says, "In accordance with Anwar's wishes." The Act of Killing begins and ends in the rooftop courtyard where Anwar once killed for kicks and where, to our horror, he smilingly demonstrates his murderous method of beheading his victims with wire (a technique he learned from The Godfather. Cleaner and less messy, he explains).

As if that weren't troubling enough, we watch Oppenheimer's evident fondness for his subject increase as the film progresses. He says: "I related to Anwar. I felt for him. It must have been hard for him." He talks about bringing Anwar "back into the human fold." The extent to which we think the film has done so hinges, it seems to me, on our reactions to two scenes late in the film. In the first, Anwar plays a torture victim in a reenacted interrogation scene. Wire is tightened around his neck and tugged. Is Anwar playing to Oppenheimer's camera, again, when he says he can't repeat that scene? Is his dormant conscience reawakening at that moment? Is he suddenly struck, for the first time in almost 50 years, by what he once did? The second, more significant scene occurs at the film's climax, when Anwar returns to the courtyard where he exterminated so many of his compatriots. He seems chastened and repentant, but is he? Might he be playing to the camera again? Is his vomiting fit 'real'? Is his remorse?

Audiences must answer such questions, if they choose to ask them, on the basis of instinct and observation. A couple of recent Al Jaazera documentaries*** on the genocide and the public response to The Act of Killing, however, provide circumstantial, albeit inconclusive evidence at odds with Oppenheimer's view that Anwar Congo has finally reached the promised land of remorse. In one Al Jaazera interview, Anwar seems a frightened man and expresses his fear that the net of justice might be closing in on him. Conrad said: "Fear always remains. A man may destroy everything within himself; love and hate and belief, and even doubt, but as long as he clings to life, he cannot destroy fear." Anwar's fear is palpable, but his capacity for doubt, self-criticism and remorse seem questionable. In one of the Al Jazeera documentaries he falls back on the tried and tested tyrants' defence of anti-communist virtue, infirmity and old age, before stating, without a moment's hesitation: "I don't feel guilty."

Whatever our individual view of Anwar Congo, there remains the live question of his long-dead victims. Emil Fackenheim famously described the massacred Jews of Europe as, "the presence of an absence." In a pointed reference to Fackenheim's comment, and as a reminder of the Palestinians' own Shoah or an-Nakba, poet Mahmoud Darwish named his final book, In the Presence of Absence. The victims of the Indonesian pogroms of 1965-66 are a similar ever-present absence in The Act of Killing . Oppenheimer says: "It is the humanity of the film's perspective that represents the victims. They're haunting every frame." And yet, although we've learned to call Anwar by his first name, as if he were a family friend, next to no explicit mention is made of them in the film.

During an Oppenheimer masterclass at the Open City Docs Festival, a woman in the audience expressed her doubts about the way The Act of Killing grants Anwar centre stage: "I couldn't care less if he were coughing his intestines up." Oppenheimer responded spikily by saying he had made the film for those capable of sympathizing with Anwar (and not, he implies, for her). I felt considerable sympathy for the women in the audience. The film foregrounds the kind of barbarians we see discussing the 'pleasures' of raping fourteen year-old girls, recounting their delight in inventing new ways of killing, singing the jolly songs they once sang as they bounced on tables, beneath the legs of which their victims lay dying agonizing deaths. Many may feel the quality of mercy to be severely strained by such conversations and reenactments. My recent experience suggests audiences will spend more time talking about Anwar and his friends than their victims over the coming weeks.

© Martin Gray

When I interviewed Oppenheimer, our conversation turned to the way his Jewish origins might have shaped the film. Our talk turned to Claude Lanzmann's Shoah (1985), Volker Schlöndorff's The Tin Drum (1979), and Rainer Werner Fassbinder's Veronika Voss (1982). We then filtered out into a discussion of the Holocaust. He says: "The official story didn't talk about the Holocaust. Ageing SS officers were still boasting about it. It keeps everyone in their community afraid." The parallels with Indonesia are obvious. Oppenheimer adds: "I grew up with the notion that the aim of all culture, morality and politics is to prevent that kind of thing ever happening again. Unfortunately the phrase 'Never Again' has been tragically taken to mean this should never happen again to us. I heard perpetrators in Indonesia saying: 'If you want this to happen, then keep digging. I understood that it was my moral responsibility to intervene, because here was a risk of history repeating itself." And yet, at the Open City Docs Festival, Oppenheimer had responded to the intervention of the above-mentioned woman by saying: "The moment you bring survivors into the film, the viewer disengages." I wouldn't. Would you?

Oppenheimer has said elsewhere that he found it impossible to film survivors of the Indonesian massacres, as to do so would endanger himself, his crew, and his subjects. He says he had to film covertly in rural Indonesia and tell the authorities that he was making a film about an irrigation project. Yet The Act of Killing joins a growing number of documentaries that refuse to let silence prevail about the genocide, among which are a number of films that do interview survivors. In her documentary The Women and the Generals (2010), Swedish director Maj Wechselman interviews some of the women falsely accused of involvement in the failed coup attempt of 30 September, which left six generals dead, was falsely blamed on the PKI, and provided the pretext for Suharto's seizure of power. The women were imprisoned without trial, and repeatedly raped and tortured.

In Robert Lemelson's documentary 40 Years of Silence: An Indonesian Tragedy (2009), four families speak out about the loss of loved ones during the massacres. On the film's website Lemelson says: "It is our hope that more people, especially Indonesians, will become aware of this tragic history, from the perspective of the victims." It is regrettable that The Act of Killing sees things primarily from the point of view of the perpetrators. Nonetheless, despite Oppenheimer's occasional errors of judgment and the film's absences, this is a thought-provoking film, the likes of which we have never seen before. Documentaries, whatever form they take, and even if they don't satisfy our need to know, get us talking and thinking. We must join Indonesians in expressing our gratitude to Oppenheimer for having sparked a prairie flame of discussion, one that we hope will leave Indonesia's mass-murderers singed, if not scorched.

* Joshua Oppenheimer’s video The Globalisation Tapes: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cPy5t7BVYCg

** John Pilger’s film New Rulers of the World: http://johnpilger.com/videos/the-new-rulers-of-the-world

*** Al Jazeera 101 East report on the genocide and The Act of Killing: http://www.aljazeera.com/programmes/101east/2012/12/2012121874846805636.html

Trailer for Robert Lemelson's 40 Years of Silence: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=N-07wttSEx4

Trailer for Maj Wechselman’s The Women and The Generals: http://www.wechselmann.se/en/2013/03/26/the-women-and-the-generals/

|