|

For a good many years, at least from a potential viewer's viewpoint, the short film had a most curious existence. Filmmakers everywhere made them, but outlets for screening them were few and far between. For a brief period between the demise of the double-bill and the current, ad-loaded, single movie experience, they would play a supporting role to main features at cinemas, and back in Film4's more adventurous early days, they cropped up regularly as space fillers between features. Short film festivals, meanwhile, did and still do provide a ready-made platform for filmmakers to screen to the ticket-holding few, assuming the festival's selection board likes what they see, of course.

YouTube and (especially) Vimeo have since changed everything, of course, but before the advent of these open digital platforms, just what was it that drove budding filmmakers to invest time and effort into works that precious few people were likely to see? There are a number of good reasons, as it happens. The first and most common is to use the film as a calling card for you and your hopefully individualistic talent. If you've never made a film and harbour a yearning ambition to be a feature director, then you tend to need something to convince those with the necessary investment capital that you have what it takes to sit in the director's chair. It's even better if the money men see the short film in question at a festival and come knocking at your door with an offer based on the potential they see in you as a filmmaker. And it has been known to happen. Short films are also a great way to experiment with ideas and techniques with minimum financial outlay and maximum control of the product. Even back when 16mm film was the medium of choice for aspiring directors looking to make a short film, an enterprising soul could usually borrow a Bolex camera, blag some date-expired monochrome stock and sweet-talk their friends into investing a few days of their time on what they were smilingly assured would be a barrel of fun and a career-launcher for all. For others – myself and a small number of like-minded friends included – short films evolved as a seemingly natural extension of other art forms in which we were already experimenting. Sometimes this proved to be an end in itself, resulting in a gallery piece that was screened over a period of a few days and then put into storage. Just occasionally, the artist in question would go on to experiment on larger scale and expand those short film ideas into a fully fledged feature. David Lynch, anyone?

Partly as a result of the restrictive nature of these viewing outlets, we still only tend to discover a filmmaker's early short films after they have achieved a degree of acclaim as a feature director, when the films in question find themselves in demand as DVD or Blu-ray special features. Intermittently this will uncover some real gems – I'll give a personal shout for Paul Thomas Anderson's Cigarettes & Coffee (1993), David Lynch's The Grandmother, Martin Scorsese's The Big Shave (1967), Gasper Noé's Carne (1991), Jean-Pierre Jennet's Foutaises (1989) and Jason Reitman's In God We Trust (2000), small gems all. Occasionally, there is enough interesting material to justify a stand-alone DVD release of a single director's short films alone – Luis Buñuel's early masterpieces Un Chien Andalou and L'Age D'Or certainly justified getting their own DVD and Blu-ray release from the BFI, and the now almost impossible to find collection of short films by François Ozon is a treasure trove of fascinating and revealingly autobiographical work. What particularly intrigues about these early shorts is the window they can open to the development of what would later become signature ideas and techniques of the filmmaker in question. Sometimes that process in the gradual one, while in the case of Songs From the Second Floordirector Roy Andersson, you can pinpoint the exact moment where the style for which he is now known was fully crystalized.

So what of Joshua Oppenheimer, the bold and gifted director of two of the most remarkable and disturbing documentary films in recent years, The Act of Killing and The Look of Silence? I'm guessing I'm not the only one who was unaware of his early work, a fascinating and deliciously unpredictable blend of documentary and full-on experimental cinema. Second Run has brought together 12 films here that vary so greatly in style, content, and length that even randomly picking three to get you started will not really prepare you for most of the others in the collection. And you really should not watch these in a random order; the collection has been arranged chronologically and deserves – indeed needs – to be viewed in that order, ideally in a single, extended sitting. This is something I discovered at an early stage of my own first viewing of the films on this DVD and is even facilitated by the disc itself, which automatically plays the next film as soon as the current one concludes. This also prompted me to abandon my usual approach of covering teach of the films individually and choose instead to examine the work as a collective whole. There are films here about which whole essays could be written, but surely the main (and many would argue only) reason to include the unambiguously titled Camera Test – which runs for just 77 seconds and appears to be exactly what is claimed by the title – is to provide a timeline launching point for the films that follow, as this young would-be cosmologist takes his first tentative steps in a medium about which he previously knew little and even actively disliked. Intriguingly, the 57 second long Light Test – which immediately precedes Camera Test in the disc chronology – shows Oppenheimer already experimenting with imagery, editing and jolting juxtaposition in a manner that would be put to more politically minded use the following year in The Challenge of Manufacturing.

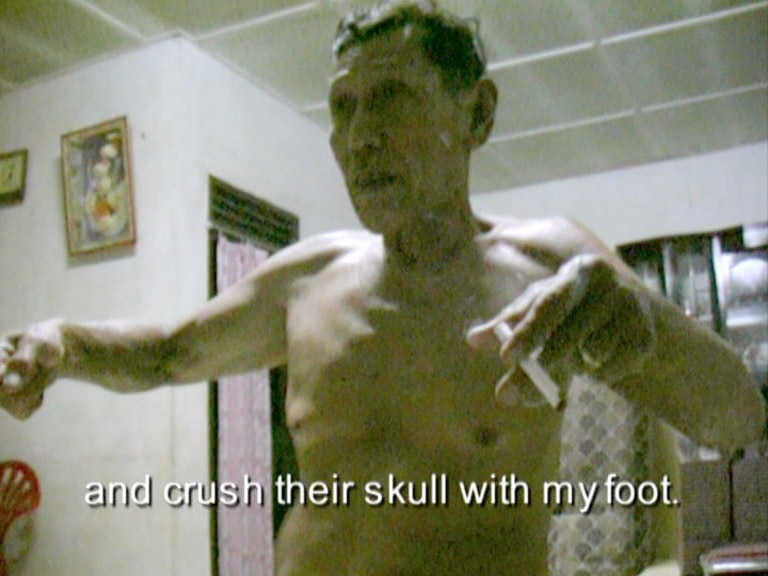

What quickly becomes clear is that Oppenheimer was not interested in telling stories in the traditional narrative manner, but regarded film as a medium of artistic expression where just about anything could and should go, resulting in cinematic blend of pop art, surrealism and Dadaist abstraction. And yet there is clear thought and purpose at work here, with a surprising degree of structural glue provided by the political undertones evident in the often multi-layered soundtracks and the manner in which they are married to or playfully contradict the imagery, and the sometimes provocative manner in which that footage is juxtaposed. Oppenheimer also has a marvellous ear for music and how to use it to underscore or counterpoint his visuals to make a political point, as in the sequence in The Globalisation Tapes in which an underpaid worker who is cheerfully spraying a pesticide that is making her ill and killing her comrades is cut to the melodious tones of The Carpenters singing On Top of the World. It's a technique that reaches a chilling peak in the wonderfully titled Muzak: A Tool of Management that uses an extract from The Globalisation Tapes in which death squad leader Pak Sinaga cheerfully explains how he used to kill communists, his horrifying words delivered in broken subtitles and his voice replaced by the mind-numbingly upbeat musak of the title. Elsewhere Oppenheimer and his collaborators Jacob Silber and Christine Cynn cut imagery to music with the energy and skill of top-of-their-game music video directors, but weaved into the fabric of a larger work as these sequences are, their effect is more thrilling than is would be as a stand-alone piece, like an unexpected orgasm of sound and vision that explodes mid way though abstract love play.

Some of the shorter films play almost as sketches of ideas for possible later development, imparting information without exploring its cause and effect in any detail but handled with a wit that still raises a smile or the occasional eyebrow. A favourite here is the one-minute long 2000 Land of Enchantment, where footage of inmates at an all-female prison is intercut with identically graded shots of a cheery telesales operator, seemingly unrelated imagery that is soon revealed to be directly connected in a surprising way. Elsewhere, Oppenheimer and his team are more gleefully playful, something a title like A Brief History of Paradise as Told by the Cockroaches should clue you into even before you've watched a pair of tethered cockroaches chatter away like they've been possessed by the spirits of Beavis and Butthead. These very same voices also provide the hyperactive narration for the 2002 Market Update, an enjoyable 2002 poke at the weasels who work on Wall Street.

But the real meat in this collection lies in the longer films, where Oppenheimer is able to expand on the one, two and three-minute experimentations to explore a wider variety of techniques and how they can be made to work with and effortlessly dovetail into one another. It also allows him to more distinctly develop his political voice and to takes his first steps in a technique that has since become his signature, as he befriends those whose views and actions he may deplore so that they will express themselves openly for his camera. This is first evident in the 1996 Hugh, a monochrome portrait of an evangelical bigot who spends his spare time in front of a mobile billboard publicly denouncing homosexuality, and engaging in fundamentalist argument with considerably more open-minded passers-by. Even scarier, despite being confined to the soundtrack, are the right-wing militiamen whom Oppenheimer engages in phone conversation by pretending to be one of their number in the 1996 These Places We've Learned to Call Home, a deeply unsettling blend of paranoia, conspiracy theory and portents for the future that is delivered with disturbingly persuasive conviction. He also toys more with format and technique in these films – it was a while before it dawned on me that documentary material, interviews and even the story itself in wonderfully titled and mesmerising The Entire History of the Louisiana Purchase were probably all fabricated.

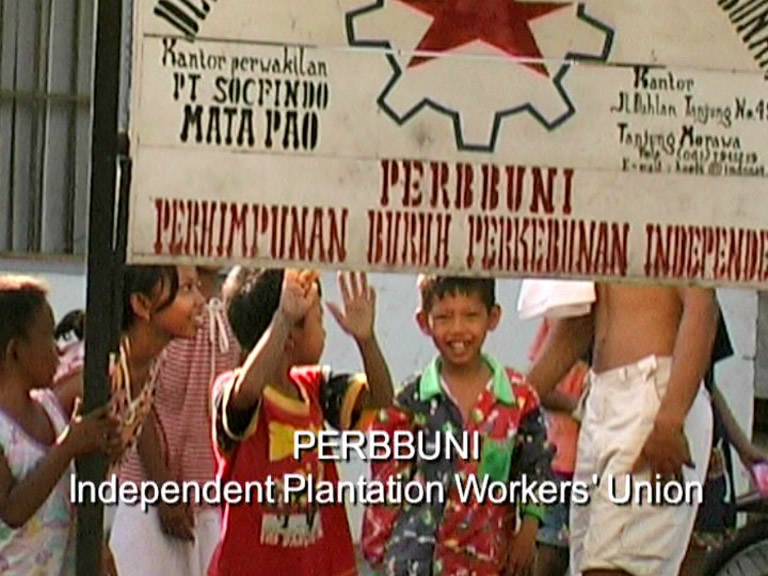

But the crowning achievement here is, a tad ironically, the one film that Oppenheimer neither shot nor directed, acting instead as producer (and, I'm guessing, editor – his signature all over it) with regular collaborator Christine Cynn, neither of whom have a credit on the film. This is actually a work of three parts, each written, directed and filmed over the course of 3 months by rank-and-file members of Perbbuni, the Plantation Workers' Union of Sumatra, and was intended to inspire workers around the world. And it really is superb. I realise I'm speaking as an animal of political protest here, but this really is eye-opening, upsetting and intermittently inspirational stuff, providing a sobering look at the lives and the lot of Sumatran plantation workers, the damaging effects of globalisation on emerging economies, and how the actions of the World Bank are ensuring that some will get rich by forcing others into abject poverty and keeping them there. The mass murder of Indonesian communists by supporters of the 1965 coup is also the subject of heated discussion here, a countrywide atrocity that was later to become the focus of The Act of Killing and The Look of Silence. This is a film that should be made mandatory viewing in every school in the western world.

Not having seen or even been aware of any of the films in this collection before popping the DVD into my player I really wasn't sure what to expect, and was surprised, fired up and genuinely inspired by what I saw. It took me back to a time when I too was thrilled by the possibilities of film and video as a medium for artistic exploration and expression, but seeing what Oppenheimer achieved over the course of seven years made my own efforts and those of many (though not all) of my immediate contemporaries look structurally and thematically a little anaemic by comparison. This is experimental cinema at it's thoughtful, risk-taking and politically committed best, and has added weight to my conviction that Oppenheimer is emerging as one of the most important and committed documentary filmmakers of the modern age.

This proved one of the trickier calls of the years so far, given that the films in this collection were shot on a variety of media and equipment and cut with library footage and film extracts, much of which has been treated with a range of film and video effects. Some of the original material was also likely in less than perfect condition, but all 12 films have been restored for this release, and while some visible flaws remain, the results are generally very pleasing. Earlier, shot-on-film works like Hugh still have more than their share of dusts spots and some very visible splice marks, but the image is stable and the contrast appropriately punchy, and it displays a nice level of high speed film grain. That there is noise on some of the video material is hardly surprising given that many were likely shot on analogue equipment or mini-DV in available light and then subjected to a variety of post-production DV effects. When the image is in its pure and unaltered state, however, it generally looks fine. For the most part, all of the films look as good as you could expect them to, and given their largely SD original format(s) I can't see how a Blu-ray release would have substantially improved on the picture quality here. All are framed in their original aspect ratio of 4:3 except Land of Enchantment, which is 16:9 anamorphic and the only film that looks as if it was shot on HD.

The Dolby 2.0 stereo soundtracks have also been restored for this release and are in very good shape, with clear rendering of the sometimes complex layering of a variety of different audio material, including newly recorded and archive sound, a wide variety of music (this sounds particularly good), telephone conversations, sound effects, and who knows what else. There are some rather loud pops on the soundtrack of Market Update, but given the clear reproduction of the dense mixing of sound elsewhere, these could well be deliberate.

Interview with Joshua Oppenheimer (23:08)

Usually I'd suggest saving any extra feature until after you've watched the film or films that they accompany, but just this once I'm going to recommend that you take a look at this one before settling down for the films themselves, as hearing what the affable Oppenheimer has to say about some of them definitely enhanced my appreciation and understanding of what he had set out to achieve. I was certainly intrigued to learn that his technique of befriending those that others would demonise (with bloody good reason) grew from the experience of suffering a homophobic attack, and a growing desire to understand how it felt to be like those whose views he was repelled and bemused by. I was also fascinated to learn that he initially went to university to study cosmology and theoretical physics, that he grew up with a real dislike of cinema, and that the decision to switch to filmmaking was an almost epiphanic one. The influence of Serbian filmmaker Dušan Makavejev is briefly touched upon, and some fascinating background is provided on the making of specific films, from the friend who played a saw to attract the title creatures for A Brief History of Paradise as Told by the Cockroaches, to the nature of the collaboration with the plantation workers during the making of The Globalisation Tapes. Rather nicely, Oppenheimer describes the short films here as "taking tentative steps into a world I am seeking to understand."

Booklet

Rather than analyse the films themselves on a technical or artistic level, writer, event and film producer, presenter and curator Gareth Evans, who has known Oppenheimer professionally and as a friend for some years, uses the essay that occupies the bulk of this 24-page booklet to explore them in a fractured, almost avant-garde literary manner that plays like a direct reflection of the art and structure of the films themselves. Not a straightforward read, but like the films it ultimately rewards your patience and attention. There's also a short but useful piece by Andrea Luka Zimmerman on the Vision Machine Film Project (2001-2007), which was co-founded by Oppenheimer, Christine Cynn, Michael Uwemedimo and Zimmerman herself. The main credits for all of the included films are also provided.

Personal circumstances (again!) delayed my review of this release, but once I started watching the films I found it impossible to break away, and there were moments when I was bouncing in my chair with glee at what Oppenheimer was doing with film and video. Those with an aversion of experimental cinema may struggle a bit here, but that's their loss, and it's worth knowing that there is very real purpose at work throughout and that it comes through clearly in even the more avant-garde pieces. Impressively presented, as ever, by Second Run, this is an absolute must for anyone already wowed by Oppenheimer's groundbreaking features and especially those of us who believe that film can be every bit as adventurous an artistic medium as painting or sculpture. Highly recommended.

|