"Every new development added to the cinema must, paradoxically,

take it nearer and nearer to its origins. Cinema has not been invented!" |

André Bazin, from The Myth of Total Cinema, 1947 |

"I am Kino-eye. I am a mechanical eye. I, a machine, show you the world

as only I can see it. I free myself from today on and forever from human

immobility, I am in constant motion, I draw near, then withdraw from objects,

I crawl under them, I climb onto them . . . I turn on my back . . . I swoop and

soar with rising and falling bodies. This is I, apparatus, manoeuvring in the

chaos of movements, recording one movement after another in the most

complex combinations . . . My road is toward a fresh perception of the world.

Thus, I decipher in a new way the world unknown to you."

|

Dziga Vertov, from Resolution of The Council of Three, 1923 |

In his round-up review of 2013*, published online by Sight & Sound beneath the strapline "Highlights of a triumphant year for the art of documentary," cineaste-cum-critic Robert Greene implied that we have entered a "Golden Age of Nonfiction." It certainly feels that way. The prodigious quantity and dazzling quality of the documentaries produced last year suggests directors are being drawn, in increasing numbers, to a medium less fettered by script and storyboard than narrative cinema, a medium perhaps, therefore, more capable of coherent response to the complexities of history and the modern world. Narrative cinema, at its best, offers profound insight into the human condition; when it renders the past, it can help us understand and feel history (as my colleague's recent review of Steve McQueen's 12 Years a Slave reminds us); sadly, it so seldom attempts to do either that documentary has its work cut out to make up the shortfall.

In an age and a world that daily reminds us of the ancient Chinese adage, "You will be cursed to live in interesting times," we need documentary to make sense of life. The more 'interesting' our times become, the saner seems Einstein's advice: "Learn from yesterday. Live for today. Hope for tomorrow. The important thing is not to stop questioning." Documentary asks questions on our behalf and takes us closer to the delightful, devilish details of life; in a cynical age of disinformation and homogenization we need it, now more than ever. The signs are auspicious. Documentary is flexing new muscles and striding toward fresh possibilities.

In 1995, the Dogme Manifesto declared: "Today a technological storm is raging, the result of which will be the ultimate democratisation of the cinema." While many of us were mourning the inexorable shift away from photographic cinema, the sudden appearance of affordable new digital technologies was liberating film production and distribution. Documentarians can now reach new audiences more easily than ever. They can consider contemporary realities with unprecedented immediacy and previously unimaginable techniques. Never before has the camera been so flexible and free. Never before have so many been so well equipped to fulfil cinema's early promise and the medium's mission, not only to tell illuminating stories but also to record actually existing life as it is, or was lived.

Robert Greene concluded his Sight & Sound piece by calling on mainstream critics to treat non-fiction with respect and expressing the capitalized hope that 2013 "might be the year we look back on as the Year the Documentary Couldn't be Denied." Below, I'll offer some thoughts prompted by that comment and list a few of my own non-fiction favourites from 2013, before reviewing Greene's "top film of last year": Lucien Castaing-Taylor and Véréne Paravel's magisterial documentary Leviathan – a film that epitomises all that is unique about documentary, points to the future of cinema, and inadvertently focuses our attention on cinema's past.

Engaging though Greene's comments were, I baulked at his insinuation that cinematic epochs are defined less by "theoretical constructs" than by audience enthusiasms. The relationship between film practise and theory may have broken down, maybe irreparably, since the ideas of Alexander Astruc and André Bazin informed the films of the French New Wave, but Greene himself is, paradoxically, living proof that filmmaking and criticism still co-exist comfortably. Film criticism should relay intelligent thinking about cinema to audiences more often than it does. As Steinbeck said: "Ideas are like rabbits. You get a couple, learn how to handle them, and pretty soon you have a dozen." I'll also, therefore, draw on the ideas of others to consider Leviathan in relation to cinema's origins and, on the grounds that cinema cannot be what it might be unless it remembers what it once was, I'll place the exciting developments Greene highlights in theoretical and historical context.

In the Beginning Was The Image |

|

From the dioramas and panoramas of cinematic pre-history, through the pioneering early experiments with moving photographs, and on into the silent era, cinema was seen primarily as fairground fun, a succession of increasingly sophisticated optical entertainments. When D.W. Griffith announced his departure from the American Mutoscope and Biograph Company on 31st December 1913, he claimed to have "revolutionised motion picture drama" and "founded the modern technique of the art." It might be more accurate to say Griffith steered the infant art form toward the spectacular and founded Hollywood, even if his hyperbolic claims came to seem less ludicrous after he'd changed film forever with Birth of a Nation (1915) and Intolerance (1916). Griffith's grandiose claims, and critic James Agee's characterisation of him as the midwife presiding over "the birth of the art," did equal disservice to documentary and to cinema's first pioneers (Eadweard Muybridge, Étienne-Jules Marey, John Roebuck Rudge, the Lumière brothers, William Friese-Greene, George Méliès, Thomas Edison, et. al.).

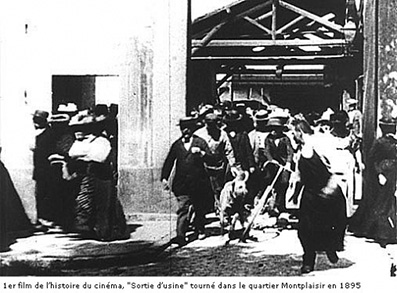

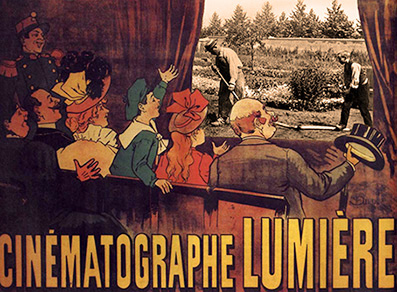

The history of moving images, lest we forget, began with documentary, with films like the Lumière brothers' Workers Leaving the Lumière Factory (1895). Martin Scorsese went some way to setting the record straight in his 3-D homage to silent cinema, Hugo (2011). Scorsese's film includes excerpts from both a documentary and a fantasy: the Lumière brothers' The Arrival of a Train at La Ciotat (1896) and George Méliès's A Trip to the Moon (1902). In so doing, Scorsese reminds us – as he did done in his homage to Italian neorealism, My Voyage to Italy (1999) – that formal cross-pollination is stitched into the fabric of cinema, that hybrid films are as old as cinema, and that audiences have always been as excited by great documentary as by narrative cinema. Messrs. Lumière's L'Arroseur arrosé/The Sprinkler Sprinkled (1885) may have been the first fiction film, but it is significant that, although it was marketed as an entertainment, audiences were actually less astonished by the acting in it than by the movement of leaves in the wind; significant partly because leaves had never been seen to move in the theatre at that point in time.

As Rudolf Arnheim noted in the Winter 1939-40 issue of SIGHT AND SOUND (as the magazine's masthead appeared then): "If we are to deal seriously with the cinema those leaves remain the essential fact." While declaring that he didn't wish to prophesy, merely face facts, Arnheim displayed striking prescience when he said: "It appears that cinema, in its present state of technique, has only two ways to get rid of its hybridism. Either it becomes photographic theatre – and it is well to remember that television, which is probably destined to supersede the cinema, succeeds only with the most artificial efforts to introduce some simple cinematographic devices into its theatrical technique. Or it becomes reproduction of reality." Fast forward several decades and we find Robert Greene saying in Sight & Sound: "The chatter about hybrid films (or chimeras, depending on your preference) – movies that play with boundaries between fiction and nonfiction – already seemed irrelevant when the year's most highly praised . . . trinity [Greene cites Leviathan, Joshua Oppenheimer's The Act of Killing, and Sarah Polley's Stories We Tell] were exhilarating audiences across the world." It might equally be argued that "chatter about hybrid films" will remain relevant for as long as a critics continue to mangle film history and downplay the achievements of documentary.

Introducing his 1967 translations of Bazin's Qu'est-ce que le cinéma?, Hugh Gray says: "Too many, for too long, notably in the United States, have preferred to think of (cinema) simply as an avenue of escape par excellence from a high-pressure life, for which we are ever seeking a new world, as it were, to live in. But such so-called paths of escape, pleasant as they are to wander in, are in reality each but a cul-de-sac. The more we see the screen as a mirror rather than an escape hatch, the more we will be prepared for what is to come." It is rare to hear such a succinct statement of the case for documentary; more often, it is argued or implied that we need more stories, that documentaries are dull and documentarians lack imagination.

Reviewing Hugo for The Guardian upon its release, the recently retired veteran critic Philip French offered an illustration of that critical imbalance; the tendency of critics, even ones as gifted as Agee and French, to malign and marginalize non-fiction. French wrote of Hugo: "The film is a great defence of the cinema as a dream world, a complementary, countervailing, transformative force to the brutalizing reality we see all around us. It rejects the sneers of those intellectuals and moralisers who see in film a debilitating escapism of the sort the social anthropologist Hortense Powdermaker impugned by calling her study of the movie industry Hollywood: The Dream Factory." Such talk of sneers amounts to a familiar smear, a conventional taking of sides masquerading as a neutral (and unnecessary) defence of fiction film against its (few) critics. Narrative cinema has been neither poor nor defenceless, while non-fiction film has tended to be both underfunded and undervalued. In particular, it is the Griersonian concept of film as "an instrument of public thinking," and the idea of an investigative, inquisitorial cinema fearless in its determination to talk truth to power, that has been most in need of champions and defenders. At minimum, those who love documentary and are discomforted by the increasing intrusion of entertainment values into non-fiction forms should demand a counterbalance to ubiquitous dream worlds, parity of esteem between fabricated fables and documentaries, and an informed criticism which recognises that hybridity began long before Clio Barnard and Joshua Oppenheimer were born.

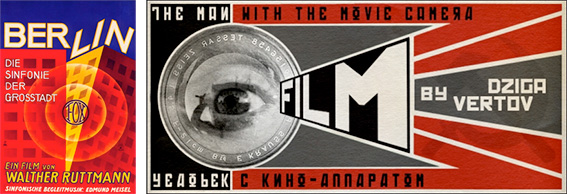

Even as the talkies became established, early non-fiction landmarks like Walter Ruttman's Berlin: Symphony of a Metropolis (1927) and Dziga Vertov's Man With a Movie Camera (1929) were showing what cameras could do with real life. Even before that, the classics of the late-silent era were blending fiction with documentary verisimilitude: in 1923, for instance, Jean Epstein filmed on the dockside streets of Marseilles for Cœur fidèle; in 1925 Sergei Eisenstein immortalized the steps of Odessa for Strike; and, in 1928, Anthony 'Puffin' Asquith took his cameras down the escalators of the Tube for Underground. Ever since cinema broke out of the studios, then, even fiction features have been documentary, even fiction films record the attitudes, faces, fashions, and streets of their times. If ever there was cinéma pur, it lay in the ideal Griffith described in a pep talk to his unit during the shooting of Intolerance: "We have gone beyond Babel, beyond words. We've found a universal language, a power that can make men brothers and end wars forever." Which begs the old questions Can cinema be useful? Can documentary be cinematic? Is it art? – questions which films like Leviathan answer in the affirmative.

Jacques Rancière argues, in Film Fables, that cinema's true potential was nipped in the bud by Hollywood and the talkies, which prevented it becoming what it might have been. Echoing André Bazin's idea that silent cinema reached it's artistic peak in 1928 (I'd argue it did so with Dreyer's La Passion de Jeanne d'Arc), and Bazin's description of that moment of rupture as the dismantling of an ideal city, Rancière argues that the ideal of an Esperanto of images was quickly compromised by its enemies: money, the talkies (la coupure du parlant), and narrative. Godard once said, "A film should have a beginning, middle, and an end, but not necessarily in that order." Werner Herzog once described Godard as "intellectual counterfeit money when compared to a good kung-fu film." Billionaire movie mogul Sir Run Run Shaw, who died on 7 January and who made a fortune from kung-fu movies, once said, when asked about his tastes in cinema: "I particularly like films that make money." In Kill Bill (2003), Quintin Tarantino pays homage both to Godard and Shaw. The conversation between films is ongoing, as is the struggle for the soul of cinema – between those who cherish its capacity to enlighten and inform, and those who cynically exploit its possibilities in order to pick the public's pockets.

Long before the midpoint of cinema and the arrival of neorealism, it was already clear there would never be such a thing either as pure fiction or non-fiction in cinema. That didn't stop Roberto Rossellini saying, maybe mischievously, certainly disingenuously: "Things are there, why manipulate them?" Nor did it stop his neorealist soulmate Cesare Zavattini calling for a new Italian cinema, a cinema that dispensed with both professional actors ("to want one person to play another implies the calculated plot") and narrative, in order to unearth "the reality buried beneath the myths of Fascism." It cannot be coincidence that there are echoes of Danton's battle cry, "De l'audace, encore de l'audace, toujours de l'audace" ("Audacity, more audacity, always audacity!"), in Zavattini's neorealist call to arms: "The cinema . . . should never turn back. It should accept, unconditionally, what is contemporary. Today, today, today."

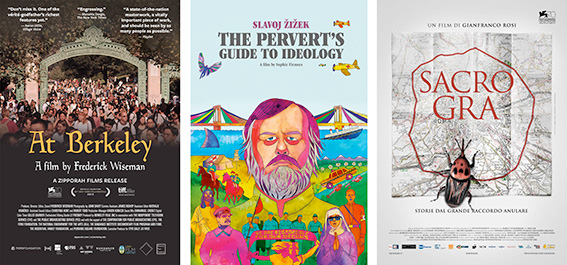

Many of the best documentaries of 2013 responded to the present, as Zavattini would have wished, with intelligence, invention, and seemingly limitless audacity. The vast range of mix-and-match styles they deployed demonstrated that there is no single way to make a documentary. The centre of Bill Nichols' classical categorization of documentary modes no longer holds. Whether the best documentaries were nominally didactic and 'expository' (Gary Fraser's Everybody's Child, Jacob Kornbluth's Inequality for All) or personal and 'performative' (Sarah Polley's The Stories We Tell, Andy Heathcote's Moo Man); 'poetic' (Gianfranco Rosi's Golden Lion Winner Sacro GRA, Cristian Soto's The Last Station) or 'observational' (Wang Bing's 'Til Madness Do Us Part, Frederick Wiseman's At Berkley), no single category or style held fast. And, while Bill Nichols' description of documentary as a "discourse of sobriety" especially suits politically urgent films like Jehane Noujaim's The Square and Xu Huijan's Mothers, even that definition fell apart in the face of profoundly funny gems like Alex Fegan's The Irish Pub and Sophie Fiennes' The Pervert's Guide to Ideology – in which Slavoj Žižek lays claim to W.S. Gilbert's epitaph: "His Foe was Folly, His Weapon was Wit." Meanwhile, two of the great fiction features of 2013, Jem Cohen's Museum Hours and Pat Collins' Silence sat so close to documentary as to drive home the point about hybridity.

| The Past Is A Different Cinema |

|

While such films scrutinizing contemporary realities or responding immediately to concrete political situations, ten of the best films of 2013 were simultaneously tackling recent history and some of the more traumatic catastrophes of the 20th Century. One of the more interesting developments of modern cinema has been the growth of compilation, collagist documentaries that mine the archives. John Akomfrah's The Stuart Hall Project, David France's How to Survive a Plague, Penny Lane's Our Nixon, Ken Loach's The Spirit of '45, Jason Order's Let the Fire Burn, Martha Shane & Lana Wilson's After Tiller, and Andrzej Wajda's Walesa: Man of Hope – all make extensive use of archival material. Moving confidently back and forth between today and yesterday, these films built from films echo Emile de Antonio's pioneering technique of "democratic didactism" or "radical scavenging." All fit within the cinematic sub genre Shola Lynch, director of Free Angela and All Political Prisoners (2012), calls "historical verité" – a genre actually best described by the more matter-of-fact term "archive-based documentary," which avoids confusion with the specific practises of cinema verité.

While those documentarians were delving into the archives to represent the past, Claude Lanzmann, Joshua Oppenheimer, and Rithy Panh all eschewed archive images in their latest films. Lanzmann's The Last of the Unjust, Oppenheimer's The Act of Killing, and Panh's The Missing Picture offer moving meditations on three of the most horrific holocausts of a corpse-strewn century (the industrial slaughter of the Nazis, the Indonesian military, and the Khymer Rouge) – using primarily probing interviews, theatrical re-enactments, and hand-carved figurines respectively. One of the most impatiently anticipated films of last year, Lanzmann's latest project serves as a correcting, consolidating companion piece to his monumental documentary, Shoah (1985). That earlier film, like Godard's equally monumental L'Histoire(s) du cinema (1988-1998), proves there is no subject so dauntingly vast and ethically charged that great documentary cannot broach it. Godard uses archive images extensively in L'Histoire(s) du cinéma; Lanzmann uses interviews instead. Despite holding radically different views on the truth claims of documentary, both directors have expressed deep unease about the destabilising effects of digitisation on cinema's capacity to provide trustworthy visual evidence. Godard imagines images of the camps being digitally manipulated by Jean-Marie Le Pen, after which "the image will no longer be a proof." Lanzmann refuses "the logic of proof" that grants images privileged status as documents of witness.

Lanzmann's position is close to the one elaborated by Slavoj Žižek when he says, "images of utter catastrophe, far from giving access to the Real, can function as a protective shield against the Real." Lanzmann insists - despite the documentary images of the holocaust in Alain Resnais' Nuit et broillard/Night and Fog (1955) and elsewhere, that the holocaust should not, indeed cannot, be shown. He says: "I made Shoah against all archives." Godard, for his part, insists – partly because of the recreations of it contained in Spielberg's Schindler's List (1993) and elsewhere – that cinema represents the redemption of reality but failed in its mission to record the holocaust, thus "totally neglecting its duty." For Godard, film is "invariably an operation of mourning and of reclaiming life." The essential power of cinema or the image-icon, he says, lies in its role as archive of history, in its documentary capacity to embalm the dead and witness historical events. It is the site where memory is enshrined, the 'museum of the real'. While archive-based documentaries were taking Godard's ideas forward, Leviathan points to cinema's capacity to record not only the moment but its own future.

As filmmakers confronted both the past and the challenges of accelerated change, film critics have struggled to absorb the implications of digitisation and the disappearance of cinema's ontological base. One of the few critics to keep pace has been J. Hoberman (presumably he has more time now for intense thought after being dismissed from his position as Senior Film Critic of Village Voice, for whom he wrote, he estimates, about two million words). In his latest brilliant book Film After Film (2012), Hoberman reformulates Bazin's question "What is Cinema?" for the digital age. Taking Bazin's idea of Total Cinema (the photograph as a form of evidence, cinema as the objective "recreation of the world") as his starting point, Hoberman assesses what a post-photographic, twenty-first-century cinema might look like. He asks what has changed between Bazin's description, in The Ontology of the Photographic Image (1945) of the photograph, still or moving, as "a hallucination that is also a fact" and art historian Julian Stallabrass's description, in Gargantua: Manufactured Mass Culture (1996), of digital image manipulation as "a technique that lends itself to the production of useful lies." Like Stallabrass, he suggests that photography has been superseded, if not the desire to make images.

Hoberman's chilling conclusions are that "with the advent of CGI, the history of motion pictures was now, in effect, the history of animation," that "in the universe of The Matrix (1999) Bazin's dream arrived as a nightmare, in the form of cyber existence: Total Cinema as a total dissociating from reality," and that "With Avatar (2009), the tantalizing promise of Total Cinema – now decisively post-photographic – was viscerally experienced: unbearably distant, yet overwhelmingly near." Much as we may loath The Matrix and love Avatar, we should look to neither for portents of film's future. We might more productively look to documentary for indications of what cinema might look like, and in particular, to Leviathan – one of the most artful, awe-inspiring, hypnotic, and unsettling digital films of recent years.

In What is Cinema? Bazin describes Thor Heyerdahl's Oscar-winning documentary Kon-Tiki (1951) as a film "snatched from the tempest." Bazin points out that the Scandinavian scientists aboard Heyerdahl's celebrated raft didn't intend to make a film when they set sail in 1947: their primary purpose was to recreate the conditions of Pre-Columbian sea exploration in order to prove that South American peoples might have discovered the South Pacific islands of Polynesia many millennia earlier. That they returned with a rough and ready record of that amazing ethnographic expedition incidentally proved, Bazin says, that "it was evident already by 1952 that there could be no witness to the stature of the enterprise comparable to the movie camera." The 16mm footage the Kon-Tiki crew shot provided Bazin with celluloid evidence for his argument that cinema arose, not from scientific endeavour, but from an idealistic mission to recreate the world in its own image and to provide increasingly accurate representations of reality. With Leviathan, Lucien Castaing-Taylor and Véréne Paravel offer us another film snatched from the tempest, a film that takes representations of reality into the realm of feeling as much as fact.

Lucien Castaing-Taylor is already familiar to adventurous audiences as co-director, with Ilisa Barbash, of the critically acclaimed Sweetgrass (2009). That elegiac, exquisitely beautiful film followed a group of shepherds as they drove their sheep to summer pasture across the mountains of Montana for the final time. For Leviathan, the Scouser teams up with France's Véréne Paravel to create a darker film that charts a more dangerous, often deadly, but equally ancient way of life. Here, the camera focuses on rain-lashed mariners not sun-kissed shepherds, on violent seas not placid peaks, on entrenched industrial practices not passing rural customs.

Leviathan rolls and pitches with the crew of the FV Athena as that hulking vessel trawls the deep Atlantic and the coastal waters off New Bedford, Massachusetts – the port from which Melville set sail on the whaling expeditions that inspired Moby Dick. Like Melville's literary leviathan, Castaing-Taylor and Paravel's magisterial tour de force drops us onto heaving decks amid the red-raw realities of slaughter at sea and whips our land legs from beneath us; like Melville's legendary novel, their always exhilarating, often disturbing film possesses an almost biblical, mythic quality; but this is a distinctly, viscerally, literally immersive cinematic experience. Leviathan takes the breath away. It is a kaleidoscopic, kinetic optic-sonic film poem that takes us where words cannot: the camera plunges us beneath the spumy waves with marine matter, places us above the rising and falling prow of the ship, propels us skyward to rotate among circling seagulls, drags us about among twitching fish carcasses, noses up against tattooed muscular masculinity, and strains, in extreme close-up, at salt-stained, brine-battered, wrinkled human flesh.

In 87 astonishing minutes, Leviathan deciphers, in a new way, a world unknown to us. It confirms André Bazin's belief in a cinema's mission to record reality, Dziga Vertov's belief in its capacity to conquer time and space, and Jean Epstein's belief in cinema as a unique medium combining art and science, thought and feeling, motion and light. It proves Vertov's argument that the perfected camera can, where the imperfect human eye cannot. "We cannot improve the making of our eyes," said Vertov, "but we can endlessly perfect the camera." By placing a dozen light, waterproof GoPro cameras in the hands of the Athena's crew, by lashing their cameras to wooden poles and affixing them to helmets, Castaing-Taylor and Paravel make the dreams of avant-grade innovators like Epstein and Vertov real. Melville's mighty fable insists that narrative, though all too often shallow, can plumb profound depths; Leviathan plunges us beneath the ocean waves and takes the early experiments of Epstein and Vertov to new heights. In one vertiginous scene, the soaring camera is inverted so that seagulls seem to float upon the sea; it's an image Dziga Vertov would have loved. It's also a magnificent demonstration of what digital cinema – affordable, mobile, flexible, fluid – can achieve.

The disorientating opening scenes of Leviathan present a convincing repost to those of us who prefer the photochemical imperfection of photographic film to the frosty precision of pixel grids, the warm luminosity of contingent celluloid to the blankness of numeric digital data files; who cry out, still, for the purring pulse of projected filmstrip, for the flickering temporality, texture, and grain of cinema's traditional material base. There are times the film is not only exquisitely cinematic, but even, yes, painterly; as it is in the sequence a crew member showers away the salt, sweat, and slime of a day's hard graft, his body distorted by steam on the lens in ways that recall the work of Francis Bacon.

As the film begins, perspectives shift, shadow and light slides in and out of focus, abstract images dance across the screen no less beautifully than in Len Lye's Free Radicals or Stan Brakhage's The Act of Seeing with One's Own Eyes. As the film progresses, clues multiply, the ink-black ocean rears into view beneath dark dawn sky, colours appear, sailors and their ship are revealed, a bulging net is winched aboard, disgorges its slithering haul into slimy hold. Right off the bat, the film establishes a charged atmosphere of menace. Lurching back and forth between opaque illusion and blurred actuality, between radical subjectivity and digital hyperreality, Leviathan is both inscrutably supernatural and recognisably documentary throughout. A film about the sea and those who fish it must be so; it must combine the mysterious and the mundane.

Great cinema calls forth considered criticism and Leviathan has been as widely and intelligently reviewed as any film I can remember, but, in the general rush to praise the film's formal innovation, an important aspect of the film has slipped through the net: the attention it pays to the lives of the men of the Athena. For all its poetry, sensuality, and shifting perspectives, this, is a film about work too. The film's recognition of the nitty-gritty of daily labour is as welcome as it is rare. The inquisitive inventiveness of Castaing-Taylor and Paravel's kinetic camerawork recalls Charles Burnett's neorealist independent classic Killer of Sheep (1977). Burnett's portrait of a black slaughterhouse worker's life in the L.A. ghetto of Watts showed African-Americans themselves on the screen and provided rare, raw footage of the dirty work done by those who prepare the food we eat. Leviathan, too, takes us into the abattoir, albeit onto a factory floor that moves beneath the feet. Like Burnett's film and Nikolaus Geyrhalter's great documentary Our Daily Bread (2005), it lifts the lid on the labour and industrial processes behind the tins on the supermarket shelves and the food on our plates. Geyrhalter's film points the camera at an abattoir worker as she receives squealing piglets off the conveyor belt, clamps them in iron vices, and snips off their sexual organs with steel secateurs. In Leviathan we watch with similar fascinated horror as two fishermen impale a stingray on their hooks, one holding the fish steady while the other slices off its fins. This is a film as bracing and, occasionally, revolting as it is ravishingly cinematic.

The sea, repository of our deepest fears and source of sustenance down the centuries, breeds a race of men apart. "No man will be a sailor," said Dr. Johnson, "who has contrivance enough to get himself into jail; for being in a ship is being in a jail with the chance of being drowned." Neither discomfort nor danger ever deterred either the men of New Bedford or of Castaing-Taylor's native Liverpool from pushing off into the icy Atlantic from their opposite shores. Leviathan doesn't shirk from showing the backbreaking labour of a bloody, often brutish vocation. The fishermen Castaing-Taylor and Paravel film (and who film themselves) slash skate with cleavers, shuck scallops, crack open clams, and hack cod to pieces. They do so while buffeted by gale force winds and battered by driving rain. Visitors only when ashore, homeless when afloat, these are hard men descended from hard men. They are also dextrous, proud, and bound by the comradeship of those who do dangerous work (as the roll call of ships lost at sea in the film's closing credits suggests). That dexterity is evident in a scene in which one mariner skilfully prizes oysters from their shells, with impressively lightning speed; that proud camaraderie is clear in a tender moment a man lights cigarettes for himself and his colleague. Castaing-Taylor and Paravel worked the same gruelling 20-hour shifts as the crew of the Athena and they must have finished their daily shoot as exhausted as the crew member who films himself, dead on his feet, nodding off to sleep while watching TV.

In their unforgettable documentary The Forgotten Space (2010) – which bears the subtitle: A Film Essay Seeking To Understand the Contemporary World In Relation to the Legacy of the Sea – the late Allan Sekula and Noël Burch consider the sea as the lacuna of modernity and crucial space of globalisation. They ask if containerization hasn't turned the sea of exploit and adventure into a lake of invisible drudgery and thrown the world out of balance. In their Notes for a Film** they say: "Nowhere else is the disorientation, violence, and alienation of contemporary capitalism more manifest, but this truth is not self-evident, and must be approached as a puzzle, or mystery, a problem to be solved." Leviathan helps us solve that puzzling, mysterious problem by taking us behind the scenes of globalisation. It peeks behind the curtains of an economic order in which, as Sekula and Burch say in their film: "Ships now resemble floating warehouses, plying fixed routes between producing countries and consuming countries, while factories become ship-like, stealing away in the dead of night in search of cheaper labour." Leviathan depicts, in exquisite detail, aspects of a world in which some ships are also becoming factory-like.

Leviathan will not, however, be remembered for the attention it pays to the nitty-gritty of working lives or for the glimpse it offers into the destructive fishing practices that have depleted fish stocks globally. It will be remembered, for years to come, as the film that announced the arrival of digital documentary as a refined art form. In the introductory Extracts section of Moby Dick, Melville's Sub-Sub-Librarian quotes from The Book of Job: "Leviathan maketh a path to shine after him." This cinematic leviathan paves a path others will surely follow. Leviathan reminds us of the forgotten space that is the sea and shows what extraordinary things can be achieved with digital cameras, a limited budget, and a surfeit of imagination. The cinema that Bazin and Vertov hoped for has arrived.

*Robert Greene's round-up review of 2013:

http://www.bfi.org.uk/news-opinion/sight-sound-magazine/comment/unfiction/best-2013-cinematic-nonfiction

**Allan Sekula and Noël Burch's Notes for a Film:

http://www.theforgottenspace.net/static/notes.html

|