|

– Part 1: The Films –

Humphrey DeForest Bogart was one of those old-school Hollywood stars that I always found impossible to resist. James Cagney was another, and I’ll watch the likes of Katharine Hepburn, Spencer Tracy, Edward G Robinson, Bette Davis and a fair few others in just about any film they graced. I always had a particular fondness for Bogart, however. He was a movie tough guy who could take a beating as well as dish one out, and like Cagney and Robinson, he wasn’t handsome in the traditional Hollywood glamour mould. Cartoons of him often elongated his face until it was three times taller than it was wide, and they tended to also emphasise his chiselled features, his upturned eyebrows, and his widow’s peak. His scarred top lip was tall enough to house the sort of spectacular cowboy moustache that I couldn’t ever imagine him growing, and it often seemed stay locked in place when he spoke, which he did with a most distinctive nasal lisp. He appeared in his first play at the age of 22 and eventually landed a movie contract with Fox, scoring his first film hit with The Petrified Forest in 1936 in a part with which he had already had considerable success on the stage. But it was to be another five years before High Sierra (Raoul Walsh, 1941) cemented his position as a bona fide star, by which point he had already turned 40.

In no time at all, Bogart was a household name and quickly became one of the most admired of all American screen actors – in 1999, the American Film Institute named him the greatest male star of classic American Cinema. It’s not hard to see why. Bogart had charisma dripping out of every pore, and at his best could be an electrifying screen presence. He also starred many of the finest films of the classic Hollywood era. Try this lot for size – The Maltese Falcon (John Huston, 1941), All Through the Night (1942), Casablanca (1942), To Have and Have Not (1944), The Big Sleep (1946), Dark Passage (1947), The Treasure of the Sierra Madre (1948), Key Largo (1948), The African Queen (1951), Beat the Devil (1953), The Caine Mutiny (1954). He was married four times, lastly to Lauren Bacall, whom he fell in love with during the making of To Have and Have Not, and despite a 22-year age gap and their share of colourful rows, they remained devoted to each other right up until Bogart’s death from oesophageal cancer at the unjustly premature age of 57.

Bogart was known affectionately by his friend and the public at large as Bogie, a nickname given to him by his friend Spencer Tracy back in 1930. When I was a young kid, this used to make me snigger, as in the UK at least, bogie was commonly heard slang for something that you picked out of your nose. Only later did I discover that it was also American slang for a cigarette, the name of the pivoting housing for the wheels of a railway carriage, and if you altered the spelling slightly (but not the pronunciation), it’s also a common golfing term and the name given to an unidentified and potentially hostile aircraft. These days, I also have to take a step back from a name I am so familiar with to contemplate the notion of a movie tough guy icon whose first name was Humphrey.

As is often the way with Indicator releases, the six films in this set are not as widely known and seen as the titles listed above. Four of them were made by Bogart’s own production company, Santana Pictures (named after his boat), and all six were distributed by Columbia. All feature Bogart in the lead except The Family Secret, one of only two pictures made by Santana in which he did not take an acting role. Unsurprisingly, all are of considerable interest, and despite the sometimes uneven quality, there are still a couple of absolute belters here.

As usual, I’ve covered each of the films separately, and in an effort to prevent this review growing to gargantuan size and complete it before the summer fades, I tried hard not to run away with any of them. Well, that was the plan, but… As a result, this is one of my lengthier reviews, with the special features for all six discs detailed on page 2 on a film-by-film basis after coverage of the films and the sound and vision specs.

If you were somehow new to film noir and wanted an overview of its key defining traits, the 1947 Dead Reckoning wouldn’t be a bad place to start. On the other hand, if you’ve already embraced the many pleasures of this dark and delicious subgenre, you’ll quickly find yourself very comfortably at home here.

As the film begins, bruised and battered former paratrooper Rip Murdock (Humphrey Bogart) dodges the police and ducks into a church. From the shadows, he quietly attracts the attention of the priest, Father Logan (James Bell), also a freshly discharged paratrooper, to whom he tells the story of how he came to be on the run from the law for a crime he claims not to have committed.

It all starts when he and his trusted friend and comrade, Sergeant Johnny Drake, return to the US at the end of WWII and find themselves being swiftly driven to catch a train to Washington. In the course of their journey to the capital, they discover that Johnny is to be awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor and that Rip is to receive the Distinguished Service Cross. Rip is bowled over, but Johnny is strangely concerned about the publicity this will attract, and when the train stops and photographers board to get pictures for their papers, Johnny quietly hops off and onto another train. Rip takes it on himself to locate Johnny and find out why he ran, an investigation that begins in Johnny’s home town of Gulf City. When Rip checks into what appears to be the town’s best hotel, it quickly becomes clear that Johnny has anticipated his arrival, having booked a suite in Rip’s name and already called for him under the pseudonym of Mr. Geronimo, a name shouted by paratroopers when they jump from their planes. When Johnny fails to call again later as promised, Rip becomes concerned, and when he learns that a man died in a burning car wreck on the very evening that Johnny said he’d call, Rip tricks his way into the morgue to see the body. It’s burned beyond all recognition, but the melted remains of a sorority pin that Johnny always carried confirms Rip’s worst fears. Having already discovered that Johnny’s real name was John Preston and that he fled to the war after being accused of murder, Rip becomes determined to uncover the truth about a crime he is convinced Johnny couldn’t have committed, and discover who arranged his suspicious death and why.

If this setup isn’t noir enough for you, then fear not, because there’s plenty more where that came from. First up, there’s Coral Chandler (Lizabeth Scott), the girl Johnny was head-over-heels in love with and who teams up with Rip to help him with his investigate the true cause of her former lover’s death. There’s wealthy nightclub owner Martinelli (Morris Carnovsky), for whom Coral used to work and who appears to still have some sort of hold on her. He welcomes Rip by inviting him to gamble in his casino with no limits, then invites him into his office to collect his winnings, serves him a drugged drink and has him deposited back at his hotel. Assisting Martinelli is Krause (Marvin Miller), a psychopathic brute who extracts information from uncooperative people like Rip by beating them viciously about the face and body whilst listening to calming music. And let’s not forget Louis (George Chandler), an old buddy of Johnny’s who works as a waiter at Martinelli’s club and who is holding a letter that Johnny gave him to give to Rip, one he is prevented by circumstance from handing over.

Dead Reckoning delivers on all of its noir credentials. Rip is hard-boiled but not tough enough to avoid taking a serious beating from Krause, and is as distrustful of women as Sherlock Holmes, while Coral is a blonde beauty who seems to genuinely fall for Rip but whose sincerity and motivations we and Rip repeatedly have reason to call into question. Martinelli is a calmly sophisticated and self-assured villain whose way with words lands him some of the best lines in the film, while the brutish Krause gets a real kick out of dishing out violence to others and represents a genuine and imposing threat. The plot bristles with unexpected and sinister twists, the dialogue and Rip’s narration (courtesy of screenwriters Steve Fisher and Oliver H.P. Garrett) both take their cue from Philip Marlowe, and Leo Tover’s cinematography plunges whole areas into deliberately concealing and suggestive shadow. It’s all solidly marshalled by director John Cromwell, whose workmanlike camera placement is intermittently elevated to a different plane, notably in the two shots filmed from the viewpoint of individuals waking from unconsciousness, one to the sight of a priest reading them the last rites.

Bogart is on fine form here, both tough and vulnerable in the manner of all the best noir protagonists and able to communicate so much with a look or the way he pronounces a simple word like “Yeah…” Some have dismissed Lizabeth Scott as a budget Lauren Bacall here, and she while she certainly lacks Bacall’s fiery chemistry with Bogie, she does rather well when it comes to the “is she, isn’t she?” uncertainty about where her true loyalties lie. Perhaps my favourite performance comes from Morris Carnovsky as Martinelli, a high-class gangster and potential supervillain-in-waiting who delivers his sometimes delicious dialogue with just the right air of confidence and self-satisfied superiority. “Brutality has always revolted me as a weapon of the witless,” he tells Rip just before handing him over to Krause for an extended pummelling.

I enjoyed the hell out of Dead Reckoning, for its performances, its snappy screenplay, its dark twists and surprises, Leo Tover’s moody monochrome cinematography, and John Cromwell’s unwaveringly confident direction. Not all of its noir credentials are on immediate display, but stick around and they reveal themselves as the story progresses. There may even be a case to be made for Rip Murdock as the quintessential Bogart noir protagonist, from a name that Raymond Chandler must have wished he’d come up with to the fallibility of his surface tough guy cool. A damned fine opener that had me itching to progress to the next film in the set.

The 1949 Knock on Any Door gets off to an absolute belter of a start. It’s 1930s Chicago and the police chase a dark-dressed and hatted figure into a nightclub and out of the rear exit. A patrolman shoots, but the figure shoots back and takes the cop down, while local residents scream and look on from balconies in alarm. The still unidentified figure then walks over to the fallen cop and empties his gun into his body, and in no time at all the cops are rounding up anyone and everyone with police record, including a young Italian-American named Nick ‘Pretty Boy’ Romano (John Derek). It’s a superbly shot and edited opening scene that crams a good ten minutes of setup storytelling into a thrillingly compact two. Consider my attention soundly grabbed.

The cops charge Romano with the crime, but he vehemently protests his innocence and insists on calling his lawyer, Andrew Morton (Humphrey Bogart). When Morton answers the phone, he somewhat surprisingly tells Romano to take a hike and returns to the chess game he is playing with his wife Adele (Candy Toxton, credited here as Susan Perry). He grumbles that this kid is nothing but a hoodlum, to which Adele responds with stony silence and the iciest of accusatory stares. This eventually prompts Morton to begrudgingly reverse his decision and pay the desperate Romano a visit (quite why she is guilt-tripping him later becomes clear), and after talking to the boy he decides to take the case.

Go into this film cold, and there’s a good chance you’ll be making a few predictions about where the film will go by this point. I certainly was. If you find yourself doing likewise, then get ready to have a few of those expectations knocked down over the course of the next hour or so. The first presumption I made was that that the film would stay with Morton as he investigates Romano’s claims, which it does and then doesn’t. Morton digs around, talks to a few people, and gathers information, but in no time at all we’re at the first day of Romano’s trial. District Attorney Kerman (George Macready) makes a savage and prejudicial opening statement, but when Morton has his chance to address the jury, he elects to tell them the full story of his history with Romano and the societal pressures that shaped him into the young man he has become. This unfolds in flashback, and despite Bogart being the headliner here and Knock on Any Door being the first film from Santana Productions, he effectively becomes a supporting character for its entire midsection. Here it becomes all about Romano, how misfortune, poverty, keeping the wrong company and some bad life decisions steer him towards a life of crime, despite the positive influence of Emma (Allene Roberts), a young shop girl he falls for and eventually marries.

Particularly for an American film made at the tail end of the 1940s, Knock on Any Door has a strongly progressive ring without feeling preachy. Key to maintaining this balance is Romano himself, a brutalised victim of an imbalanced and prejudicial system who is also someone who does himself no favours and is too pig-headed to recognise the escape routes that are occasionally presented. That said, when he slugs his boss after being balled out for pausing his back-breaking work for a few seconds to have a smoke, I was right in his corner, despite the poverty that his resulting unemployment plunges him and Emma back into. As a result, by the time the film returns to the courtroom, it’s easy to find yourself rooting for this clearly frightened young man and for the determined Morton’s efforts to convince the jury of his innocence.

Bogart is again on excellent form here, and when delivering impassioned speeches either to individuals or to the court, he gets to express an emotional range rarely seen in what could be described as more typical Bogie roles. In the pivotal role of Nick Romano, then relative newcomer John Derek (the same John Derek who went on direct his later wife Bo in the multi-Razzie Award winning Bolero in 1984) is more convincing than claimed by some of the more hostile contemporary reviews, ones that were also outraged by the film’s progressive liberal leanings. Director Nicholas Ray – whose riveting directorial debut, They Live by Night (1948), so impressed Bogart he offered him this film – does a robust job throughout, but regularly elevates the film to a higher level with whole sequences that thrill, surprise, or even startle. It can also be seen to be a first step on a thematic path that six years later would lead to another tale of socially disconnected and troubled teenagers, Rebel Without a Cause, which remains Ray’s most widely celebrated film.

Knock on Any Door blends social realism with courtroom drama to surprisingly involving effect, in part because it doesn’t sugar-coat its young protagonist and peppers his story with unexpected twists, including some dark turns of fate that I genuinely didn’t see coming. The point is made on the accompanying commentary track that a sizeable portion of the contemporary audience would likely have read the hugely successful novel (by Willard Motley) on which John Monks Jr and Daniel Taradash’s screenplay is based. A modern audience unfamiliar with this book, however, will likely be guided more by expectations shaped by film tradition, and that’s part of what makes Knock on Any Door feel fresher and more surprising than it theoretically should seem all these years later. These story twists, Ray’s skilful direction, the sincerity of the performances, and some fine work by cinematographer Burnett Guffey and editor Viola Lawrence, make this a consistently arresting and sometimes sobering watch. And I’m sure I won’t be the only newcomer to this film who was surprised to learn that it was also the origin of that famous catchphrase of rebellious youth: “Live fast, die young, and have a good-looking corpse.”

As a side note, how refreshing it is to see a film made in the 1940s featuring a black supporting character who is not a maid, a hotel bellhop (Dead Reckoning has both), or a rich white man’s butler (The Family Secret). He may be saddled with a racially inspired nickname, but Romano’s friend Sunshine Jackson (Davis Roberts) is presented as his equal, the only hint of racial prejudice directed his way being an underhand trick pulled to rattle him in court by the ruthless Kerman.

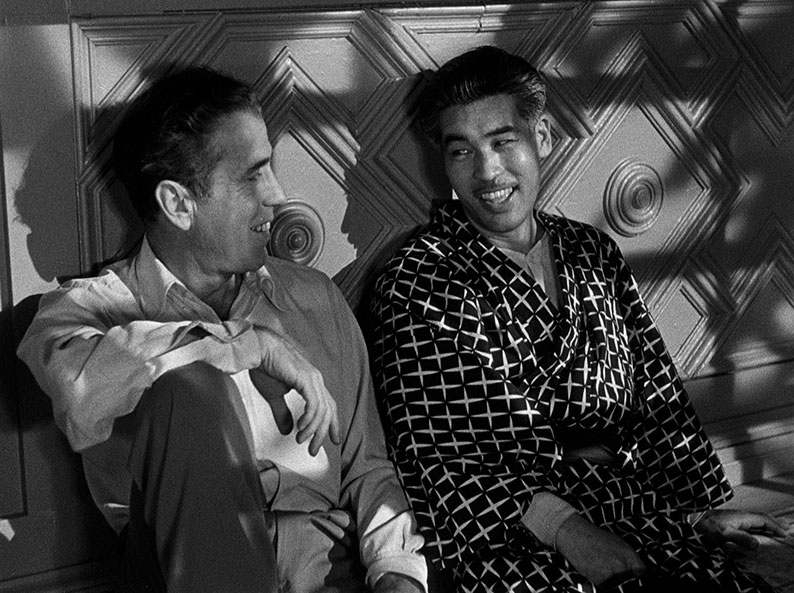

It’s post-war Tōkyō* under American occupation, and former Lieutenant Colonel Joe Barrett (Humphrey Bogart) has just arrived in the city in which he lived and ran a bar before the outbreak of World War 2. The bar is now off-limits to American personnel, but he secures clearance to visit anyway, and is greeted warmly by his good friend and business partner Ito (Teru Shimada). When I say warmly, they hug, exchange pleasantries, then launch into a friendly but highly physical bout of judo, throwing each other across the room until they are too tired to continue. The whole thing is observed with an air of mild disapproval by Kanda (Hideo Mori), Ito’s bulky and suspicious-looking assistant, who uses this distraction to try and steal Joe’s cigarettes and watch. The sound of a woman singing then sends Joe scurrying enthusiastically upstairs, only to discover that the voice belongs not to the Trina Pechinkoff (Florence Marly), the presumed dead wife that Joe left behind, but a record made of her singing before the war split them apart.

A depressed Joe laments the fact that Trina died in the war, only to be assured by Ito that she is still very much alive and still living nearby. All excited at the prospect of seeing her again, Joe scoots round to her house. The maid insists that no-one named Pechinkoff lives there and that the house is owned by a Mr and Mrs Landis, but the spectacularly rude (and ever so slightly dense) Joe pushes his way in anyway and demands to see Trina. I’m guessing that just about everyone watching will be way ahead of Joe by this point and will be just waiting to see him hit with the sobering truth. This occurs seconds later when Trina appears and Joe starts telling her how much he has missed her and how glad he is to have got her back again. “I’m married, Joe,” Trina tells him, revealing that she divorced him in his absence, but after recoiling from the shock, Joe defiantly proclaims his intention to take her back. It’s just after this that Trina’s husband Mark (Alexander Knox) arrives home. It tuns out that he’s fully aware of Trina’s history with Joe, and that he’s here now to try and win her back. He informs Joe calmly that Trina is happy now, which Joe counters with the claim that, “she belongs to me, and she knows it.” Belongs? Steady on, that man. Joe then departs, leaving Trina and Mark to discuss the feelings she once had for her former husband, and us to speculate which of the two likely outcomes this love triangle will lead to. Either Mark will turn out to be a rat and be killed in an incident that will put Trina’s life at risk, allowing Joe to reunite with the love of his life, or Mark will prove to be a decent chap after all and Joe will make a noble emotional or physical sacrifice to allow him and Trina to go on living together happily ever after.

If you are still trying to guess which of these two paths the film will follow by the halfway mark, then there’s a good chance you’ve somehow never had the inestimable pleasure of seeing Casablanca. In that film, Bogart played a jaded nightclub owner in a foreign land whose establishment is visited by his lost love and her new husband, and… oh come on, if you’re reading this you must know how that slice of cinematic perfection plays out. And Joe’s not going anywhere, at least for the 60 days that his visitor’s permit allows him to stay in Japan. To be allowed to stay longer, he needs to set up a small air freight business with Ito (quite why is never explained), and to secure the necessary funding he approaches local gangster Baron Kimura (Sessue Hayakawa – birth name Hayakawa Kintarō), who as a Japanese citizen would be prohibited from launching such a business himself. As having such a firm would allow Kimura to transport goods and even personnel in and out of the country, he eventually agrees, and as token of their partnership he provides Joe with evidence that he could use to blackmail Trina into going away with him. When Joe attempts to put this information to use, however, he meets Trina’s young daughter Anya (Lora Lee Michel) and realises that he is her biological father, but finds himself emotionally corned by Kimura’s assurance that he will use the information he has on Trina to ruin her if Joe attempts to back out of their deal.

At the very start of her commentary track for this film, Nina Foire says, “Tokyo Joe is unlikely to appear on anybody’s list of best Humphrey Bogart movies,” while on his commentary for Dead Reckoning, Alan K Rode dismisses it as “not very good at all.” I’m in full agreement about the first of those statements, and while I sympathise with the feeling behind the second, I can’t help feeling it’s a little harsh. That said, I do have to admit to a degree of cultural bias here, as although it has its American heroes, its Japanese bad guys, and from an underlying western propagandist viewpoint, for an American film made just four years after the end of World War II, Tokyo Joe is surprisingly and unusually respectful in its depiction of Japan and its people. There is no yellowfacing of Caucasian actors, and none of that usual trick of casting anyone of oriental appearance in the Japanese supporting roles. All of the Japanese characters here are played by Japanese-American actors, the Japanese they speak is authentic and appropriate (my own limited skills with the language enabled me to follow almost all of the Japanese conversations, and none seemed out of place), and the American characters – Bogart included – also deliver lines in Japanese correctly. And while the majority of the film was shot on studio sets in Hollywood, much of the exterior footage was filmed on the streets of late 1940s Tōkyō, this being the first American production to be granted permission to film in post-war Japan. I’m aware that as a confirmed Japanophile this is going to be a bigger deal for me than it will be to others, and will admit that the air of authenticity this creates is tempered just a little by the various American servicemen doubling for Bogart in the location wide shots – always filmed from behind with their true identities hidden under the actor’s trademark raincoat and hat – and by the obvious fakery of the back-projection close-ups this footage is intercut with.

There’s certainly an argument for labelling Tokyo Joe as the poor man’s Casablanca. It borrows heavily from that film but lacks so much of what continues to make it such an electrifying and emotionally involving watch. The components certainly fall short here. Although intriguingly played, Trina Pechinkov is no Ilsa Lund, Mark Landis has little of Victor Laszlo’s effortless charisma, and Cyril Hume and Bertram Millhauser’s screenplay (from a story by Steve Fisher, adapted by Walter Doniger) treads familiar and sometimes predictable ground. There’s also a strong suspicion that it was pressured to toe the party line in the presentation of the American military and the Japanese locals, an aspect most evident in the largely formulaic final third. At its best, the film can still catch a willing viewer by surprise, but some of the plot points feel contrived and artificial, from the question of who put the record of Trina singing on when everyone in the bar had been downstairs for some time, to a plan to wheedle information out of an uncooperative member of Kimura’s gang that falls flat on its face so quickly, and in such a suspect manner, that the scene ultimately feels redundant to the plot. But Bogart once again delivers the goods, even if Joe initially behaves like a self-centred prick, and a warm performance from Teru Shimada makes Ito the most easily likeable character in the film. Stuart Heisler’s direction lends a touch of class to even the weaker written scenes, and he’s well served by Charles Lawton Jr’s evocative monochrome cinematography and some nicely understated work by a well-chosen supporting cast. So no, it's not one of Bogart’s best, but I’d argue that there’s a good deal more here to like and even admire than some of its naysayers have claimed.

The second film in this set tarred by Rode as “not very good at all” is perhaps a tad more deserving of the put-down than Tokyo Joe, but it will still be of real interest to Bogart fans and noir devotees alike. Here Bogart’s appearance is delayed for almost ten minutes while the scene is set, and when he does show it’s almost in a supporting role, as one of a small group of local merchants brought in on the orders of the man who seems to be being set up as the central character.

Let’s backtrack a little. We’re in the Syrian capital of Damascus in 1925 during a period of French occupation and civil unrest. The Syrian leader, Emir Hassan (Onslow Stevens), assures two smuggled-in western reporters that he and his people are fighting for their freedom and the right to self-govern, while French military representative General LaSalle (Everett Sloane) tells a larger contingency of press representatives that the French are in Syria on a League of Nations mandate that Hassan and his followers refuse to recognise. Both believe that God is on their side and will guide them to victory. Sound familiar?

A short while later, after another French patrol is slaughtered by Syrian fighters, the angry LaSalle orders that for every Frenchman murdered they will execute five Syrian hostages, a plan that his immediate subordinate Colonel Louis Feroud (Lee J. Cobb) disapproves of. Feroud suggests instead that he try to meet with Hassan and negotiate a truce, a plan that eventually meets with LaSalle’s reluctant approval, although only on the condition that Lieutenant Collet (Harry Guardino) be sent in Feroud’s place. “You’re too valuable a man!” barks LaSalle by way of explanation, convinced that the mission will result in the death of the messenger.

It’s then that we get out first glimpse of Bogart as American ex-pat trader Harry Smith, as he and four of his Syrian contemporaries sit outside Feroud’s office awaiting the Colonel’s arrival. When he appears, however, he walks straight past them to focus instead on preparing Collet for his mission. It’s only once this is done that he turns his attention to his bemused visitors, informing them that he will no longer tolerate their profiteering and suggesting that from now on they sell all of their food to the army, but at substantially reduced prices from the ones they have been charging. The Syrians are aghast, but Harry seems unflustered and immediately agrees, a response that makes Feroud suspicious of his motives. There’s no pleasing some people.

The paths of the two men cross again that evening when Harry is dining with his Syrian business partner, Nasir Aboud (Nick Dennis), and his attention is drawn to an attractive woman named Violette (Märta Torén), who is initially dining alone but is soon joined by none other than Colonel Feroud, with whom she is romantically involved. When the restaurant is hit by a terrorist attack, Feroud is called outside by one of his men and Harry takes the opportunity to lend assistance to the rattled Violette, and as he pursues her in the days that follow, it becomes clear that she has become increasingly unhappy with the officious and passionless Feroud. The course of true love is then disrupted when one of the shipments of arms that Harry has been smuggling into the city for Hassan is intercepted by the French. With the army now looking to arrest him, Harry makes immediate plans to escape the city to Cairo, a potentially perilous journey that the now desperate Violette insists on taking with him.

It may come as no surprise that Sirocco was another Bogart film that was criticised on its release for being a bit of a Casablanca knock-off. There are certainly similarities, with Bogart once playing a jaded American who has relocated to a Middle-Eastern location where he becomes involved in a love triangle with an attractive and foreign-accented woman – that both Märta Torén and Ingrid Bergman had Swedish accents seemed to seal the critical deal. The influence on some of the imagery, and even on Harry himself, of The Third Man has also been noted (including by the filmmakers), and the similarities of elements in Sirocco to those two giants of cinema can’t help but work against a film that is never as stylish, as intriguing, or as captivating as either. Then again, precious few films are.

What really differentiates Sirocco, and one of the things that makes it of interest all these years later (quite apart from the fact that civil unrest in Syria is still a hot political issue), is its downbeat tone and its unusually apolitical stance. Are Hassan’s men terrorists or freedom fighters? Are the French hostile invaders or are they there, as LaSalle claims, to bring stability to a civil war-torn country? And by supplying arms to Hassan with profit his only admitted motive, is Harry making a buck whilst aiding the resistance or enriching himself by supplying weapons to a terrorist group? All this and more is left for us to make our minds up about, or to ignore we if so choose.

The absence of establishing location footage and the casting of white Americans as Syrian and French characters does mean that Sirocco lacks the air of authenticity that a more thoughtful approach to these elements brought to Tokyo Joe, and the sombre mood makes engagement with the characters a slow process. Lee J Cobb, who when let loose could be one of the most expressive actors in Hollywood, is at the most restrained I’ve ever seen him, and Harry is the sort of character that Bogart could play in his sleep by this point in his career. Greek actor Nick Dennis is a ball of enthusiastic energy as Nasir, too much so when dancing and singing in the barber shop in which we first meet him, but his chemistry with Bogart when they sit down for a meal and first catch sight of Violette suggests the two could have made quite a double act if given more screen time. As Violette, Märta Torén is appropriately alluring, her radiant smile at is most beguiling when amused by Harry’s efforts to seduce her, and in one of his earliest film roles, Zero Mostel does a sound job as perpetually worried Syrian trader Balukjiaan.

For a film set in a time of conflict in a location where death really did lurk around each corner – as evidenced here by the almost constant sound of not-too distant gunfire and explosions that underscore almost every scene – it’s surprisingly lacking in tension and a true sense of danger, at least until Harry goes on the run and hides out with Violette in catacombs that the lost and drugged-up have made their home. It’s also a shame that the best scene comes so early in the shape of the terrorist attack on the restaurant, a smartly staged sequence whose build-up and post-explosion confusion foreshadow a similar sequence in Roger Spottiswoode’s 1983 Under Fire. It’s also the only time the surrounding conflict directly impacts the lives of all three main protagonists in a convincingly realistic way, in the process providing a teasing glimpse of the grittier and edgier movie that might have been.

The 1951 The Family Secret is the odd one out here, being the only one of the six films in which Bogart does not appear – his uncredited role was as the film’s executive producer. That said, its links to the other films in this set extend beyond being a Santana production. It stars John Derek from Knock on Any Door and Lee J Cobb from Sirocco, was photographed by Santana regular Burnett Guffey, and was co-written by In a Lonely Place screenwriter Andrew Solt. It’s probably the least well-known of the titles here, and is in some ways the least successful, yet it’s still of real interest, for its performances, the moral quagmire it throws its characters into, and for the way it foreshadows a later and far darker exploration of similar subject matter.

Young David Clark (John Derek) returns to his middle class family home one evening in a state of extreme agitation, uncertain whether to go to the police or to flee. He washes some distinctive red mud from the wheels of his convertible, mud that would confirm he was at the tavern from which he has just fled, then enters the house and tries to behave as if nothing is wrong. His mother Ellen (Erin O'Brien-Moore) is playing cards with her friends Donald Muir (Henry O'Neill) and Sybil Bradley (Peggy Converse), whose son Art is David’s best friend. When Donald has to leave, a still rattled David takes his place at the card table, but a short while later the phone rings bringing the news the Art has been murdered. Sybil is understandably distraught, but David’s father Howard (Lee J Cobb) is dogged by the suspicion that his son was aware Art had died before he gave him the bad news. He thus visits David in his room and quietly encourages him to open up about what’s troubling him. David responds by admitting he killed Art, the accidental result of a struggle that began when his drunken and jealous friend laid into him whilst angrily brandishing a knife. A shocked but supportive Howard suggests that David should immediately take his story to the police or family friend, District Attorney George Redman (Santos Ortega), and a still shaken and uncertain David eventually agrees this would be the best move.

It’s then that the previously unaware Ellen walks in and is told what has happened, and her response is somewhat different. After tearfully hugging her son, she starts questioning whether there is any evidence to tie him to the crime. When she reasons that there isn’t, she proposes that the three of them should keep quiet about the whole thing. “Why should David’s life be ruined because Art got drunk?” she asks Howard rhetorically. As a lawyer with a strong belief in doing what is morally and lawfully right, Howard is not so easily turned, and convinces David to accompany him to see Redman the following morning. When they enter Redman’s office, however, instead of confessing as planned, David asks only if there is anything he could do to help, Art being a close friend of his and all that. Redman responds by revealing that Art’s murderer has already been caught, a notorious bookie named Joe Elsner (Whit Bissell) who was overheard threatening to beat Art’s brains out shortly before he was killed. Neither David nor a morally conflicted Howard choose to reveal the truth to Redman, but things complicate further when the accused Elsner’s wife Marie (Dorothy Tree) approaches Howard and begs him to act as her husband’s defence attorney in the upcoming trial, a request he initially refuses but later feels morally obliged to accept.

It's an intriguing setup that poses a set of moral questions that get little in the way of answers. To get into specifics would mean dropping whopping spoilers, but I will say that that I didn’t buy the way the film ends for a second on either an emotional or intellectual level. Another issue is that while David is established in the opening seconds as the central character by virtue of being a first-person narrator, the more we see of him, the more of a selfish and entitled little shit he seems to be. There’s a marvellous moment in this film’s commentary track where Jason A Ney lists all of the unpleasant things that David has done, and at this point we’re only two-thirds of the way into the film. This is also just before David drunkenly tries to force himself on Howard’s attractive personal assistant Lee Pearson (Jody Lawrance), and when she fights him off, he quickly turns his attention to his friend Morten’s girlfriend Vera (Jean Alexander), whom he snogs in the kitchen behind her boyfriend’s back. By this point David has not only killed his friend, but his refusal to take responsibility for his actions has also resulted in the death of another, but here he is, trying to get his end away with his friend’s girl at his mother’s birthday party. What a trooper.

Having said that, I’d also argue that there is considerable dramatic mileage in inviting us to sympathise with a character whose actions later prompt us to question our earlier loyalties and see them in a different and far less sympathetic light – just look what Breaking Bad did with Walter White as that series progressed. There are also opportunities for social commentary in examining the morality of parents whose devotion to their child is so great that they are willing to keep silent about his involvement in a killing to prevent him going to jail. You won’t have to look far to find real-world examples of that one. The moral division between the parents here is also interesting, with Howard – the lawyer – offering moral support but in favour of David turning himself in, while Ellen is almost shockingly quick to suggest that they should cover up the crime. After being initially guided by his father, David ultimately sides with his mother, which feels less an act of self (-ish) preservation than one of abject cowardice on the part of a morally weak young man. All the ingredients are certainly here for a challenging and hard-hitting drama, but the solid groundwork laid in the first half is ultimately undone by the weak and frankly questionable turns the story takes later. The potential for a more confrontational exploration of these themes is definitely there, and was later more fully realised by Austrian director Michael Haneke in his 1992 Benny’s Video, a dark and punishing tale of what a middle-class husband and wife are willing to do to conceal a brutal killing committed by their sociopathic son. And if the prospect of watching one of Haneke’s toughest films is a little too daunting, check out Damián Szifron’s remarkable 2014 anthology feature, Wild Tales [Relatos salvajes], whose fifth story, The Proposal [La propuesta], goes its own equally class-critical way with the central concept.

Working in this film’s favour is Henry Levin’s tight direction and some impressive work by a talented cast. John Derek does a sound job in an ultimately unsympathetic and even unlikeable role as David, but is quietly outshone by a nicely pitched, low-key turn by Lee J Cobb as Howard, whose inner turmoil is rarely expressed but is still visible in his expressions and his body language. Probably my favourite performance comes from Jody Lawrance as Lee, although her engagingly witty self-assurance in the office and the way she forcefully fends off David’s dunken advances are unfortunately undermined by her character’s behaviour in the later stages. Its ultimately the acting that makes the best elements work, as well as coming close to selling those that just miss the mark. And while credibility may take a hike in the final scenes, when it does deliver on its critique of middle-class family protectionism, it still makes for intermittently arresting viewing.

| THE HARDER THEY FALL (1956) |

|

Nick Benko (Rod Steiger) is a successful but crooked fight promoter in an industry that appears to be rife with corruption. For ten years he’s been trying to get sportswriter Eddie Willis (Humphrey Bogart) to join his team as its PR agent, and finally thinks he has a fighter that will pique Eddie’s interest in the shape of South American newcomer, Toro Moreno (Mike Lane). Initially, Eddie is impressed by the muscular giant that steps into the training ring, but it takes only a couple of minutes with trainer George (Jersey Joe Walcott) to reveal that Toro, in Eddie’s words, has a “powder-puff punch and a glass jaw.” Big he may be, but as a boxer he’s next to useless.

Despite Eddie’s understandable cynicism, Nick is still convinced they can clean up with Toro by making capital of his size and (manufactured) background, and by paying his opponents to take a dive in matches. Eddie’s still not convinced, but he’s currently out of work and this gig promises to pay well, so he agrees to sign on. His first suggestion is intriguing. “You’ll never kick him off in this town,” he tells Nick, “The boys’d never swallow it.” “Alright then, where do we kick him off?” asks Nick, to which Eddie replies, “California. They like freak attractions out there.” We quickly learn how someone like Nick operates when Eddie meets his wife Beth (Jan Sterling) in a bar a short while later, and even before he has the chance to tell her about his new job, two of Nick’s goons show up with a ticket for a flight to California that very evening. Nick protests this short notice and insists that he could fly out tomorrow, but the boys are not interested. “Nick says you go when we go,” they insist, handing Eddie the ticket and a wadge of cash for expenses.

A neatly shot and edited montage informs us that Eddie has succeeded in getting Toro’s name and picture into the press, pushing stories and imagery that trade on the boxer’s height and bulk. He certainly attracts a sizeable crowd for his first bout against heavyweight contender Sailor Rigazzo (Matt Murphy), but when Sailor realises that Toro can’t fight for toffee, he decides against taking the prearranged dive and starts laying into a man he now knows that he could easily beat. His more cooperative trainer responds by rubbing a towel soaked in chloroform into his fighter’s face between rounds, which causes him to quickly fall flat on the canvas. That there has been foul play is obvious to the unhappy crowd and the attending press alike, but the most potentially problematic is popular TV sportscaster Art Leavitt (Harold J. Stone), an old friend of Eddie’s who has been subpoenaed by the commission now investigating the fight. After being offered ten per cent of the money that Toro brings in by a desperate Nick, Eddie pays Art a visit and calls in an owed favour to persuade him to deliver a neutral verdict to the commission on a match that he knows full well was crooked. It’s during this sequence that the film’s dim view of boxing is laid bare, when Art screens for Nick an interview he has conducted with real-life punch-drunk boxer Joe Greb, a deeply sobering melding of drama and documentary that paints a worrying picture of the sport and the innocent Toro’s potential future in the ruthless Nick’s hands.

This is essentially the story of a once successful writer whose career has hit the skids and who is sucked into a criminal enterprise by an amoral manipulator and the corrupting lure of monetary gain. Initially reluctant, Eddie quickly discovers that his experience as a sports writer and the connections he has made make him a natural for a job that he is, on paper, morally ill-suited for. Firing him up at every turn is the ferociously driven Nick, who cares nothing for the welfare of the fighters he exploits and runs his operation almost like a mafia family, surrounding himself with loyal heavies whom he sends out to pay off corruptible fight managers and lay into boxers who fail to cooperate. Caught in the middle is the hapless Toro, an almost childlike innocent who has no idea that the fights he is winning have all been fixed, and who you know sooner or later is going to have to face a boxer of considerable skill who cannot be bought off. It’s his growing realisation of the impact that all this and more is having on Toro that presents Eddie with a path to possible salvation, though by this point he is in so deep that there are no guarantees of a happy conclusion for either man.

The Harder They Fall is perhaps best known for being Bogart’s final film, but what a swansong this is. Despite his illness, Bogart is on absolutely blistering form here, from his early cynicism at Eddie’s proposal to his duplicitous deal-making and image manipulation, and his later outrage at the extent to which Nick is cheating Toro. Counterpointing him at every step, and every bit as compelling, is Rod Steiger’s fiery intensity as Nick Benko, infusing even the simplest lines (I did wonder how much leeway Steiger was given to improvise around them at times) with the sort of energy that makes them all feel so utterly real. This potential clash of the two actors’ acting styles works here precisely because of how they so perfectly represent the characters they play, resulting in conversations that play like sparring matches, with Steiger rapidly firing verbal projectiles that Bogart calmly and confidently catches or bats aside. Mind you, the bristling dialogue of Philip Yordan’s screenplay (adapted from a novel by Budd Schulberg – see the Bertrand Tavernier extra detailed below for more on this) gives them plenty to work with, which director Mark Robson builds on by blocking and pacing whole sequences with an almost Hawksian eye and ear for action and dialogue. At its busiest, this plays almost like a verbal relay race, with one actor handing off his line to another with barely a pause for breath between.

For all its energy and wit, a pall still hangs over The Harder They Fall. Bogart was unwell throughout the production and was dealing with the pain of an as-yet undiagnosed oesophageal cancer, which is occasionally visible in close-ups in which his eyes are watering, and on a couple of occasions when his movements are stiffer than their fluid norm. Knowing this, however, makes his the sheer range of emotions he so convincingly expresses in this final screen performance feel all the more triumphant. He’s bloody superb here, and is perfectly matched against the fiery Steiger. If you’re looking for evidence of Bogart the talented screen actor as opposed to Bogart the iconic movie star, it’s all here, right up on screen. No question about it, The Harder They Fall is a hell of a performance and a movie to go out on. Sayonara, Bogie-san.

Part 2: Tech Specs, Special Features and Summary >>

|