|

– Part 1: The Films –

I’ve yet to meet anyone who is passionate about cinema who is not also a fan of film noir, a tonally and visually distinctive subset of the American crime movie. I’m sure there are film devotees out there who have no time for such movies but I won’t have them in the house. It’s a (sub-) genre that I fell in love with in my teenage years but know full well that there are still so many titles that meet the noir criteria that I have yet to see. Cue this first collection in a series of as-yet undetermined length from Indicator showcasing less widely-seen titles that comfortably wear the noir label. The release contains a whopping six feature films, a tally that looks set to be equalled by the second set, which is due in February.

Fortunately for my free time, the good people at Indicator have crammed fewer special features into this collection than they managed to find for the Fu Manchu Cycle 1965-1969 box set, which took me weeks to watch and review. There’s still plenty to get your teeth into here, including a commentary track for each film and a second one for one of them, plus a generous collection of other supplementary material, including short films, archive interviews, radio plays, galleries, trailers and more.

Perhaps the most unexpected inclusion consists of six short films featuring the comedy trio, The Three Stooges. While these films were made during a golden period for noir and the included titles have at least a thematic connection to the features that they accompany, I have trouble with the idea that anyone compiling a collection of noir thrillers and dramas thought, “You know what this set really needs to finish it off? A handful of Three Stooges comedies.” I thus suspect that Indicator already had access to these films and perhaps many others (two were included on the label’s Blu-ray of The Mad Magician, after all) and saw an opportunity to include some of them here. I have absolutely no problem with this, though I’d imagine Three Stooges fans might balk just a little at having to buy a box set of films they may have little interest in otherwise (who are you people?) in order to get their hands on restored HD copies of some of the boys’ work.

As tends to be my way, I watched and wrote about the films before even getting started on the special features, which inevitably means that some of my observations are also made by more knowledgeable others in the supplemental material, and often in more detail. When the contributors to the extras have clarified a point on which I was uncertain, I’ve amended my own coverage to suit, but if they’ve written the same thing about a film as I have, then I’ve left my take on the points in question as they are. Great minds and all that.

Before I move on I should note that I have no intention of providing a definition of film noir here – its fans will already have a sound grasp of its codes and conventions, and if you’re somehow new to it then there are a slew of articles and books out there about it that will provide the answers you seek. What I will say is that I had a fabulous time watching this superb collection of titles, none of which I’d previously seen. There’s not an even remotely naff film in here, and each has elements specific to that title to recommend it. Ah, hell, that’s enough intro, let’s get to the movies.

A woman stands on the San Francisco Bay Bridge in thick fog at night and glances anxiously at her watch. A policeman approaches her in the manner of Sgt Murphy in The Untouchables to check that she is alright and not thinking of jumping, but she assures him that she is fine. She clearly is not. Shortly after the departure of the policeman a taxi pulls up and two men get out. The first is carrying a gun and is suddenly attacked by the second, who is unarmed, which prompts a third passenger and the driver to jump out and lay in to the second man. When the driver raises a knife to plunge it into the second man’s chest, the woman’s screams, the men freeze and the scream carries over into a room in a countryside hotel, where the woman wakes from what we and she now realise was just a dream. The noise alerts the manager and one of the other guests, who burst into her room to check she is unharmed. She’s terribly grateful for their concern, and the other guest is clearly rather taken with the woman’s good looks. It’s the following morning before the woman seems to realise that this man was the passenger who was nearly murdered in her dream.

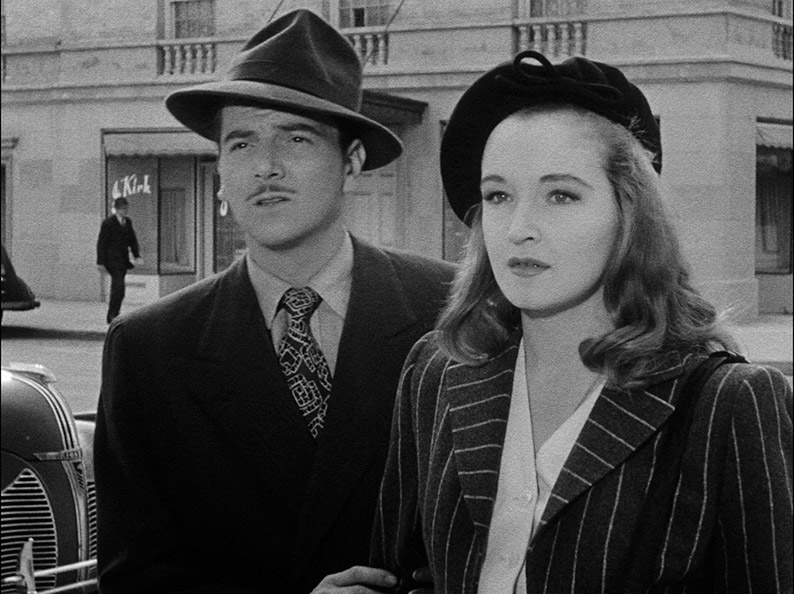

The woman’s name is Eileen Carr (Nina Foch) and the man’s is Barry Malcolm (William Wright), and over breakfast the next morning both reveal that they are staying at the hotel on a break from their wartime service. Eileen admits that she is recovering from a breakdown after the hospital ship she was serving on was sunk by enemy fire, but Barry is more cagey about the precise nature of his work, though does admit that he’s also taking a break following an assignment that rattled his nerves. Barry uses this friendly discussion to start chatting Eileen up and she appears to be similarly attracted to him, but progress is temporarily interrupted by a phone call ordering Barry to return to San Francisco to collect details of his next assignment. On the off-chance he invites Eileen to come with him and enjoy a couple of evenings out in the big city, and at that lightning speed in which relationships once blossomed in films, Eileen thinks it over for about two seconds and accepts. What neither realise is that the hotel clerk has been earwigging their conversation, and when they depart he calls The Golden Gate Watch and Repair Shop in San Francisco and informs the proprietor Schiller (Konstantin Shayne) that Barry has just left. We’re just seven minutes in and the film is already draped in intrigue.

Written by Aubrey Wisberg and directed by later western legend Budd Boetticher (as Oscar Boetticher Jr), Escape in the Fog is a tightly plotted, noir-tinged wartime thriller whose only real oddity is Eileen’s dream, which as the first half unfolds looks increasingly certain to be a premonition. This introduces an element of fantasy into a film that otherwise has its feet in the real world of international wartime espionage, and is all the more peculiar for being an isolated incident whose payoff occurs not at the film’s climax but at roughly the halfway mark. Thus Eileen is not a clairvoyant but a woman who for no explicable reason experienced a premonition that would allow her to play a crucial part in changing the destiny of a man she’d never previously met, then never had another. It almost feels as if two screenplays were melded together and explanatory elements were chopped to fit the running time.

If you’re prepared to buy into this for the sake of a film that otherwise gets so much right, however, it does serve a purpose by drawing Eileen into a plot in which she otherwise had no stake. It also helps to underscores the secret nature of Barry’s work when the worried Eileen approaches his boss Pail Devon (Otto Kruger) for information on Barry’s whereabouts, and he politely denies having ever met Barry, which has the effect of prompting Eileen to take action that will effectively close the premonition circle. And while there are a couple of questionable plot turns (an urgent escape plan devised by Barry may be fun, but it soes take some swallowing), the film nonetheless benefits greatly from having characters on both sides making intelligent decisions and planning their moves with foresight. A typically well thought-through example comes when Schiller phones the police station at which an item that is crucial to both sides is being held, pretending to be a port authority official and asking that it be delivered to him immediately. Although agreeing to his request, the desk sergeant then has the intelligence to immediately phone the port authority office to check that this is where the call was actually made from, a move that Schiller has anticipated, which is why he broke in to the port authority office at night and made the call from there. The film is peppered with moments like this and it cumulatively creates a convincing sense that the men Barry and his colleagues are hunting are as smart as they would have to be in real life to work undercover on what for them is enemy turf. As a result they present a tangible challenge, one that despite the year of the film’s production does feel tinged with the possibility of failure, which helps ramp up the tension as the finale approaches.

I really enjoyed Escape in the Fog, for its tight plotting, its solid performances, its well-defined characters and the thought that goes in to many of their actions. And yes, I even found the off-the-wall clairvoyance element oddly engaging, an aspect that, like the demonic possession in The Exorcist, you’d probably disbelieve in real life but get frustrated when characters in the film do likewise. Listen to the woman, damn you!

| THE UNDERCOVER MAN (1949) |

|

Go into Joseph H. Lewis’s misleadingly titled The Undercover Man knowing little about it, as I did, and it actually gives Escape in the Fog a run for its money in the speed with which the hooks of intrigue are sunk in. Frank Warren (Glenn Ford) and his wife Judith (Nina Foch again) alight from a train and are promptly pushed aside by a throng of photographers following an unidentified and presumably famous figure as he boards. When they reach the station foyer, the fact that their arrival is being closely observed by a seated figure is emphasised by a stylish but purposeful camera move. Judith mentions recognising this man to her husband but he deflects her comment and encourages her to use the time they have until the next train to do some shopping. He then walks over to a kiosk and quietly exchanges words with the man, who provides a simple description of a contact that Frank is due to meet. When an individual matching the given description eventually enters the foyer he walks right past the apprehensive Frank, immediately after which Judith returns with her shopping and Frank suggests they go to the hotel room and wait there instead. Everything about this opening so far suggests that Frank is either involved in dodgy dealing or is working as the undercover agent of the title and that his wife knows nothing of his clandestine activities. When they arrive at the hotel room in question, however, two of Frank’s colleagues – including the one seen at the station – are already waiting, and Judith isn’t remotely phased by their presence and even questions them about how long this latest assignment will last. OK, you’ve got me. But there’s more.

I can’t recall exactly how far I was into The Undercover Man before I had my first ‘hang on a minute!’ moment and it dawned on me that I was watching a 1949 take on the true story that was also the basis for the The Untouchables. There are clues in the opening textual roll and narration, but it’s only when we learn that Frank Warren is a Treasury Department agent who is investigating a notorious gangster whom he hopes to prosecute for tax evasion that my suspicions were confirmed beyond doubt. Further evidence for those who know the details of the case arrive in the similarity of Frank’s name to that of Frank J. Wilson, a former accountant who joined the Treasury Department and led the investigation into Al Capone’s financial dealings, one that eventually led to Capone’s conviction and imprisonment for – you’ve guessed it – tax evasion. The fact that Al Capone is not named was apparently a concession to a tightening of censorship rules when it came to the portrayal of gangsters in American movies, though with the fact that this film fictionalises aspects of a famous true story probably played its part. Yet I can’t help but question the wisdom of not giving the Capone stand-in (whose face we never see) a name and having him known only instead as 'The Big Fellow', a distinctly non-sinister nickname (‘Scarface’ it’s definitely not) that sounds a little daft when used in newsreel reports on the man’s activities.

What The Undercover Man does do particularly well is deglamourize the process of nailing a master criminal like Capone and show – albeit in a manner that compresses almost two years of painstaking investigative work into fewer than 90 minutes of screen time – that working such a case involves a lot of sometimes frustrating searching through documents, chasing of sometimes dead-end leads and talking to witnesses who are too frightened to go on the record with what they know. The film also doesn’t shy away from the notion that there are sometimes tragic consequences to investigating murderous criminals, and that it’s not always the bad guys that suffer the consequences.

If you somehow know nothing of the Capone investigation and want to go in cold, then hop to the next paragraph, but if you do then you might be surprised at some of the things that the film gets right. The focus on getting at least one of Capone’s bookkeepers to testify is a factual element that the film shares with the 1987 David Mamet/Brian De Palma take on the story, but the manner in which the jury at The Big Fellow’s trial is swapped for another after it is discovered that they have all been bribed is closer to the way it actually played out here than it is in the later movie. The film still plays fast and loose with the facts in the name of drama, notably when a key piece of evidence is literally placed in Frank’s hands by the Rosa (Joan Lazer), the young granddaughter of good-hearted Italian immigrant Maria Rocco (Esther Minciotti) just as he is in the process of quitting his job after tangible threats have been made to him and his wife. It’s a fanciful but still really effective scene, with the old woman – who speaks almost exclusively in Italian that is translated by her granddaughter – telling a story of fleeing her homeland after her husband’s murder and seeking a new life in America that would not be out of place in The Godfather, Part II. She also specifically name-checks the Mafia and The Black Hand, surely one of the first times these terms were coined in an American movie and again both later very relevant to the back-story of one Vito Corleone.

The ever-reliable Glenn Ford makes for a likeable Frank Warren and has what it takes to quickly convince us of the man’s honesty and dedication to his job. When The Big Fellow’s self-satisfied but wily attorney Edward J. O'Rourke (very nicely played by Barry Kelley) pays him a visit after he has taken a beating from the gangster’s goons and politely tries to bribe him, you know just from Ford’s past actions and current demeanour that he’s not going to be swayed. Impressively, the film resists turning Warren into a man of vengeful action, and even when pushed he remains a thoughtful and dedicated investigator who outsmarts his foes instead of out-gunning them, only falling back on his sidearm when his life is at stake. Perhaps my favourite Ford moment comes during the above-mentioned encounter with Rosa and Maria (hop ahead once again if you skipped the previous paragraph), when he responds to Maria asking him if he’s going to quit by muttering an almost imperceptible “no.” It’s a gorgeous example of the sort of performance subtlety that only the probing eye of the camera is able to pick up on and make feel as powerful as the loudest shout. There’s strong work throughout a fine supporting cast that includes John F. Hamilton as beaten-down desk sergeant Shannon, Frank Tweddell as his doggedly professional boss Inspector Herzog, and James Whitmore and David Wolfe as Frank’s colleagues George Pappas and Stanley Weinburg.

Joseph H. Lewis directs with style and purpose and the occasional eye for offbeat framing – on several occasions he positions his characters low enough in frame to leave headroom that you could fly a small plane through, and the result is oddly discomforting in a way I can’t quite put my finger on. Given that none of the lead players in this film go undercover, I’m still a little bemused by that title (an explanation of sorts is provided in the special features), and although based on a famous true case, it plays almost as fast and loose with its source material as the later The Untouchables. And while not as grand an entertainment as the later film, The Undercover Man a still a well-acted, very smartly directed and consistently gripping early interpretation of the true story of how one of the most feared gangsters in modern American history was taken down not by a squad of heavily armed police, but by a team of hard-working and determined accountants.

| DRIVE A CROOKED ROAD (1954) |

|

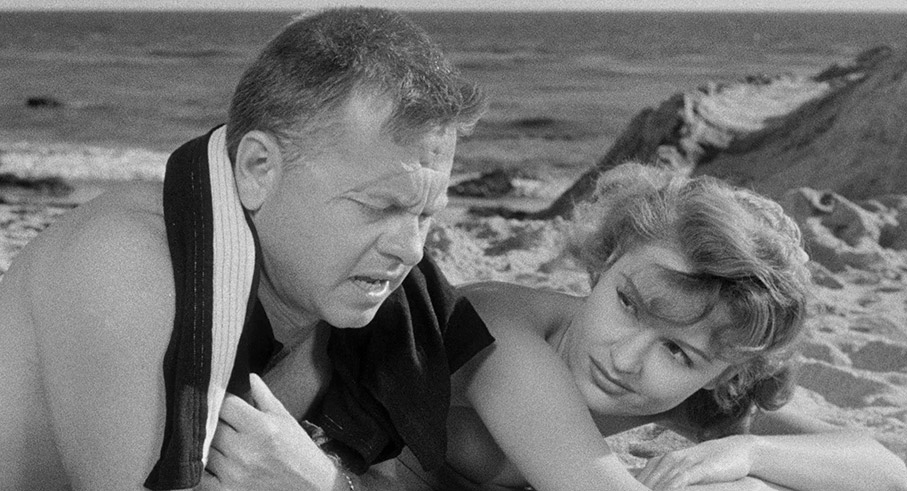

Eddie Shannon is a mechanic with ambitions to be an international racing driving who’s held back by shyness and low self-esteem, the result in part of a large facial scar he picked up in a car accident some years earlier. His colleagues good-naturedly make fun of his short stature and the fact that he doesn’t ogle every female that passes their shop, but one day an attractive woman named Barbara Matthews (Dianne Foster) brings her car in for repair and Eddie is immediately taken with her looks and her friendliness towards him. When he is later asked by his boss to go to her house to get her car going again after it has stalled, she drops enough hints for him to join her at the beach for even Eddie to pick up on. When he does so he briefly meets her friend Steve Norris (Kevin McCarthy), who owns a nearby beach house and who makes his excuses and departs shortly after Eddie’s arrival. Eddie spends a cordial afternoon with Barbara, who later asks him if he’ll take her to a party being thrown by Steve, and Eddie, who by this point is clearly smitten with Barbara, happily agrees. At the party Steve engages him in conversation about the merits of American verses foreign-made cars, a subject on which Eddie is able to wax lyrical. The next day, Steve invites him to his house and makes him a proposal that will give him the money he needs to chase his dream, but that will require him to do something that is just not in his nature...

Drive a Crooked Road is compelling for a couple of unexpected reasons, and while I’ll be getting to them I need to first cover an aspect of how the film unfolds that theoretically requires a spoiler warning, but maybe not. Hop to the next paragraph if you want to take no chances. My caginess comes from the suspicion that if you’d seen this film on its release then there’s a possibility you would not have predicted how the story unfolds, but its inclusion in a box set with ‘noir’ in the title invites a modern viewer – or at least one with even a passing knowledge of the genre – to make some early, and as it turns out, accurate predictions. Having said that, the clues are all there in the opening sequence, as Steve and his jokey knob of a friend Harold (Jack Kelly) converse after watching a race in which Eddie finished in second place. At this point in his career, Kevin McCarthy would not have been as easily recognisable as he later became, and the two could have been mistaken by the audience for race fans having a casual chat. But there’s something about the nature of the details Harold has about Eddie – master mechanic, no family, few friends, lives alone and hates it – that is just a bit too personal to have been gleaned from a casual enquiry or a driver’s reputation. He also describes Eddie as “the ripe type” and the two men only shift their attention to him after dismissing another potential candidate because he is a business-owning family man. Couple this with the genre in which the film has found a home and it seems likely from the off that Steve and Harold are after Eddie as a driver for what is probably a bank robbery, and have convinced Barbara to seduce him in order to help draw him in.

And yet even armed with this certainty regarding how things will unfold, the unhurried build-up to the moment when Steve makes Eddie a proposal that could change his life remains compelling viewing. Why? Mickey Rooney, that’s why. If you only know Rooney for his Andy Hardy movies, his multi-film musical partnership with Judy Garland or, heaven forbid, his excruciating turn as Mr. Yunioshi in Breakfast at Tiffany’s, then you’re in for a serious surprise here. I’m not exaggerating when I say that Drive a Crooked Road is built around what may well be Rooney’s finest film performance, and I’m only hesitant about proclaiming it the best because I’ve yet to see every film he made. Rooney is just terrific here, his low-key naturalism making it easy to sympathise with Eddie at an early stage and really feel for him when he starts to let down his guard and fall for Barbara. Rarely have I seen a more convincing portrayal of adult shyness on film, with Rooney perfectly capturing the opposing emotions of discomfort and attraction that do battle in Eddie’s early encounters with a woman he clearly believes is out of his league. And he never overplays it – every moment of his performance in these scenes feels so genuine and so drawn from experience that it re-awakened some of more awkward memories of my own early teenage bumbling responses to girls I just didn’t know how to confidently talk to yet.

It’s in the second half and particularly the final ten minutes that the film really earns its noir credentials and I found myself wondering how this could possibly work out well for anyone. The willingness of director Richard Quine and screenwriter Blake Edwards (yes, that one) to devote almost the whole first half of the film to what are basically character scenes has led to some commentators describing the film as dull. I couldn’t disagree more, as by the time the plot really gets under way I cared so much about Eddie that I felt I had a personal stake in how subsequent events would play out for him. Some transparently obvious back-projection in the driving scenes aside (damn you, high quality HD transfers), Richard Quine’s direction is solid and appropriately character-focussed, and Foster and McCarthy play their roles with conviction, but for me this is very much Rooney’s film and is worth revisiting just to watch him at work. There’s just one thing that bugged me (and skip this bit to avoid a reference to the spoiler I warned about earlier). Considering how important driving the difficult escape route was to their plan, I understand why Eddie watched the film that Steve shot of the route over and over, but I still have one question. Given his profession, why didn’t he just try driving it a couple of times to get a better a feel of the terrain before doing the job?

| 5 AGAINST THE HOUSE (1955) |

|

Al (Guy Madison), Brick (Brian Keith), Roy (Alvy Moore) and Ronnie (Kerwin Mathews) are four Midwestern College friends who travel across the country for an evening out at Harold’s Club casino in Reno. To avoid getting hooked and losing too much money in the process, they’ve set themselves a time limit, at the end of which they have agreed to quit no matter how much they may be winning or how much progress they may have made with any women they meet. Ronnie is convinced he has devised a system to win, but despite constantly consulting a notebook has no luck at all, while quiff-haired southerner Brick immediately approaches and charms a glamorous female gambler. When Ronnie’s system fails him again and he and Roy walk to the cashier’s booth to buy some more chips, they inadvertently find themselves standing behind a man who is quietly attempting a robbery and end up being nabbed by the police as likely accomplices. When the would-be robber grumpily concedes that he was working alone, the boys are freed and the man’s actions are mocked by the arresting detective, who claims that there is no way to rob Harold’s Club. “It’d be easier to knock off Fort Knox,” he claims before heading off with his prisoner. It’s then that a light goes on in the studious Ronnie’s head...

Even if I’d not read a word about 5 Against the House, that title and that opening scene alone make it clear that the four friends and an as-yet unidentified woman (she’s in the opening title sequence) are going to attempt to fleece the casino of a sizeable amount of cash either by gambling or pulling a con or heist of some kind, and given the detective’s words and Ronnie’s reaction, it’s not hard to predict which one it will be. So this is a heist movie, then? Well, yes and no. A heist is certainly proposed, planned and set in motion, but it’s less the film’s main focus than a framing device in which to explore more character-centric concerns. It’s this, together with some cracking first-half banter between the lead characters – full marks here to screenwriters Stirling Silliphant, William Bowers, and an uncredited Frank Tashlin, plus the precise comic timing of the dialogue delivery – that differentiates it from other heist movies of the period. This deviance from the norm clearly irritates some – there are plenty of negative user reviews on IMDb – but for me the reduced emphasis on the mechanics of the robbery and the greater focus on the lives and psychology of the characters works an absolute treat.

Let’s start with the characters themselves. From the moment we meet them, their bonds of friendship are established by the easy back-and-forth wit that peppers every conversation they have. Brick and Roy in particular are natural wise guys, but all four are able to throw lines at each other that know their friends will catch them and respond to them in kind. Not only is this a delight to watch and listen to – I genuinely laughed out loud several times – but it quickly establishes just how close they are as friends, how relaxed they are in each other’s company and how much they enjoy hanging out together. There are plenty of films that take their whole first act to do this, but 5 Against the House accomplished it in its opening couple of minutes, and during the course of that first casino visit we get to enjoy the company of all four characters. Now we’re ready to learn a little more.

At the moment it became clear that all were college students I let out a wry smile. Whereas nowadays a film featuring students would employ actors of an appropriate age, it was once common practice to cast actors in the late twenties or early thirties as students and audiences just went along with this obvious oddity. Remember Doctor in the House? Dirk Bogarde was 33 when he played medical student Simon Sparrow, and as his fellow students, Donald Sinden was 30 and Kenneth Moore was turning 40. Did we care? Not for a second. Similarly, the four actors here were their late 20s and early 30s, but at least here we’re given a reason why reason why Al and Brick appear to be a little older than the others, and that’s because their higher education was delayed by their service in the Korean war. This itself becomes a crucial plot point, as not only was the friendship between Al and Brick cemented when Brick saved Al’s life during the conflict, but in the course of doing so Brick suffered a head injury whose psychological impact landed him a spell in a veteran’s hospital and in moments of conflict still has the power to enrage him or reduce him to tears.

Despite the friendship that bonds them, all four men seem to want different things from life. Al is keen to marry his attractive nightclub singer girlfriend Kay (Kim Novak) and settle down, but in a reverse of the movie norm it’s she who is in no hurry to get hitched. Ronnie comes from a wealthy family but wants to make his mark by doing something that nobody else has done, while Brick is trying to re-adjust to civilian life by studying law, a subject he later reveals he’s never likely to succeed at. Roy is the only one who seems to have no specific goal and is attending college less for the qualification he may gain than for the opportunities it offers to chase girls and have fun. It’s this dynamic that makes the theoretically unlikely decision to rob the casino feel oddly plausible. Al treats the whole thing like a geometry problem that he has been tasked to solve and only wants to see through to prove it really can be done – at one point he even talks about returning the money after the score. Conversely, it’s the prospect of having enough money to get as far away as possible from the hospital he still sees as the root of his troubles that piques Brick’s interest and gets him on board, and while Roy initially thinks the whole idea is nuts, he’s the nearest the group has to a hanger-on and will ultimately follow the lead of his friends. As for Al’s involvement, well, if there’s a weak point in the story then that’s probably it, but I’ll leave that for the film to reveal and for you to either buy into or not. Either way, this development not only alters the tone of the film but the dynamic of the group, in a way I wasn’t initially sure about but that made more sense when I revisited the earlier scenes of Al and Brick discussing their past.

The performances of the four leads are crucial to why we buy them as friends so quickly and completely, with Brian Keith in particular proving as convincing as an emotionally damaged vet as he is as a laid-back, quick witted womaniser. We could only wish that Kim Novak’s role as Kay was as fleshed-out at those of her male co-stars, though she’s certainly sultry enough to sell the idea that Al would be completely hooked on her. Phil Karlson directs with purpose and drive and largely avoids directorial flourishes, though he clearly enjoyed the visual possibilities offered by the garage and car elevator at Harold’s Club (oh, you should see it), and in the film’s only remotely look-at-me shot suggestively frames Al beneath Kay’s raised leg in an image that is so closely mirrored by a famous image in the later The Graduate that I’d have a hard time believing it wasn’t copied directly from here.

I may have been initially a little thrown by a second-half turn of events that I’ve avoided getting specific about, but the robbery itself proves to be both ingenious and tense, and features a key early role for William Conrad as a casino worker. It also doesn’t conclude quite how I had expected, and ends on a short sequence that the subtlety and honesty of one performance alone makes touchingly effective. We’re left with a few questions to answer about what would happen next, but this still proves a satisfying ending to a very smartly scripted, directed and acted heist-themed social drama. One question I do have about the film is not answered in the special features and may just be a sign of how times have changed. How the hell were the filmmakers able to shoot a movie about robbing the real-life Harold’s Club casino inside the real-life Harold’s Club casino?

| THE GARMENT JUNGLE (1957) |

|

The 1957 noir drama The Garment Jungle opens in dramatic fashion, as business partners in dressmaking company Roxton Fashions, Walter Mitchell (Lee J. Cobb) and Fred Kenner (Robert Ellenstein), have a blazing row about whether the company’s workers should be allowed to join the union. Fred, the company’s chief designer, is all for it, but Walter is always looking for ways to cut costs and swears he’ll never let the union in his shop. As Fred angrily departs, a maintenance crew are just putting the finishing touches to the freight elevator, but when Fred steps inside and presses the button to descend, the cage plunges over 20 stories (from the speed with which it falls it looks more like a 120, but we’ll let that slide because it’s genuinely alarming) and kills him. An investigation rules his death as an accident but Fred’s widow and local union organiser Tulio Renata (Robert Loggia) are convinced that Fred was murdered on the orders of mob boss Artie Ravidge (Richard Boone), to whom Walter has been paying protection money for some time to keep the union out of the firm. When a troubled Walter calls Ravidge to question him on this, the gangster smooth-talks him into believing he had nothing to do with what he maintains was a terrible accident. It all sounds plausible until Ravidge’s ice-cold button pusher Mr. Paul (Wesley Addy) leans into shot to light his cigarette for him, a man that sharp-eyed viewers will recognise as the maintenance crewman who was checking the fateful elevator earlier.

Into this maelstrom – on the day of Fred’s funeral no less – walks Walter’s adult son Alan (Kerwin Mathews), who’s been serving abroad for the past three years and has decided to come home with the intention of joining the business, something his father always wanted but that Alan showed no interest in doing before. He arrives in time to hear one of the industry’s top buyers and Walter’s glamorous lover, Lee Hacket (Valerie French), tell Walter about the suspicions voiced by Fred’s widow, and a short while later he’s being shown around the shop floor by foreman Tony (Harold J. Stone) when Tulio shows up and drops some strong hints about Walter’s mob connections and how they may have led to Fred’s death. Alan is carrying a grudge from the past regarding his father’s reluctance to be straight with him, and thus decides to do his own digging on this score and pays a visit to Tulio and his fiery Italian wife Theresa (Gia Scala), who lay out for him just what has been going on regarding Walter’s dealings with Ravidge.

Right from the off it seems clear that The Garment Jungle is going to kick against the red scare politics of the day by making a case for the unionisation of an industry in which the exploitation of shop floor workers was once rife, and which is still the subject of controversy in countries where such sweatshops remain depressingly common practice. Central to this is Tulio, who in his first verbal conflict with Walter may give the impression that he’s a bit of a rabble-rouser, but when visited by Alan he is humanised as a loving father and devoted husband and shown to be a man of deep conviction. For him, the unionisation of the industry brings no personal gain, it’s all about creating a fair working environment in an industry in which he has a reputation as a top garment cutter. He’s aware of the danger this puts him in and his verbal sparring with Theresa is not the result of her disagreeing with his politics, but her fear of what will likely happen to him if he continues his crusade.

Aside from its sound political viewpoint, the film also scores in its convincing presentation of a criminal foe that really does seem able to exert considerable power, arranging the death of Walter’s partner for his pro-union sentiments and invading a late night union meeting and beating Tulio and the middle-aged regional organiser senseless with clubs and chains. Later, Alan and Theresa become trapped in an apartment when Mr. Paul and his goons park their car outside and just wait for them to leave, having driven them in there in the first place by tossing Theresa’s baby’s shoes at their feet from a passing car with the chilling threat, “Hey, Mitchell, lay off or the kid’s legs will come next.”

The performances are strong across the board, with the ever-excellent Lee J. Cobb in full 12 Angry Men mode when furious and vulnerable alike, and as the energised Tulio, a standout Robert Loggia really does seem to believe in every passionate word that comes out of his mouth, though he is matched at every turn by Gia Scala as a sexy and incendiary Theresa in their scenes together. As mob boss Ravidge, old hand Richard Boone brings a welcome third dimension to a role that could so easily have been a cartoon villain, while Wesley Addy only has to casually amble into a room and smile to suggest what the sinister Mr. Paul is capable of.

The Garment Jungle was directed by Robert Aldrich, who was already a bit of a noir veteran after The Big Knife and Kiss Me Deadly. Well, most of it was. Or maybe just some of it. The story varies from person to person and even Aldrich’s own accounts sometimes differed in their detail. What we do know is that he had completed much of the film before falling out with notorious studio boss Harry Cohn, the exact reason for which once again varies depending on who’s telling the story. Aldrich was fired and Vincent Sherman was brought in to finish the film, and while it seems likely that he did reshoot some of Aldrich’s material, accounts differ considerably over how much. Aldrich claimed that 70 per cent of the final film is his, whilst Sherman has said that he reshot 70 per cent of Aldrich’s footage. Now I may not have a mathematics degree, but those two figures just do not tally. Whatever the truth, the finished work not only looks and plays wonderfully but there are no obvious problems with continuity of style – if I hadn’t been told that there was a director switch towards the end of the shoot, I’d honestly never have suspected.

It’s been argued that The Garment Jungle was partly a riposte to the anti-union slant of the earlier On the Waterfront, which also featured a belting performance from Lee J. Cobb and whose location shooting Aldrich had been keen to emulate. But it also stands on its own feet as a tough and sometimes tense drama that pits ordinary working men against the powerful mobsters and absolutely comes down on the side of the former. I’ve only one real issue with the film, one I can’t discuss without dropping an almighty spoiler that those who’ve not seen it yet might accidentally glimpse. For those who know it, my problem relates to a relationship that develops with a timing and speed that for me throws all decency to the four winds. I shall say no more.

The 1958 The Lineup, a feature film adaptation of a then-popular TV show, certainly starts with a bang. As passengers alight from an ocean liner in San Francisco, a porter grabs a suitcase from the top of a pile of passengers’ luggage, shoves it through the window of a waiting cab and runs off. The cab speeds away and when a patrolman tries to flag it down the cabbie runs him over. Although fatally wounded, the policeman gets off a single shot that hits the cabbie, who crashes his vehicle and dies at the scene. Cue the opening titles. Phew.

Looking into the case are Inspectors Al Quine (Emile Meyer) and Fred Asher (Marshall Reed), who when having the contents of the case examined find a figurine stuffed with smuggled heroin. They initially suspect its rightful owner, Philip Dressler (Raymond Bailey), of being the smuggler, so replace the drugs with a harmless substitute, return the case to Dressler and have him closely watched. When they talk to Customs official Chester McPhee (Francis De Sales), however, he informs them that tourists are being used as unknowing couriers by drug smugglers and that Dressler is likely an innocent party here. The detectives thus turn their attention to the dead cabbie’s apartment, where they find evidence of drug use and indications that a second heroin shipment may be due in the following day. A short while later the body of the porter who grabbed the bag at the port washes up in the bay.

Up until this point the film has played as a police procedural in the manner of the TV series on which it was based, and while it’s interesting enough, Inspectors Quine and Asher do not exactly light up the screen. To be honest, as individuals they’re actually kind of dull, law enforcement drones with little in the way of personality or charisma. After the body of the porter has been discovered, however, that all changes. It’s then that we’re introduced to the film’s principal bad guys in the shape of sociopathic gangster Dancer (Eli Wallach) and his mentor Julian (Robert Keith), who in their first couple of minutes of screen time prove more interesting than Quine and Asher managed to be during the previous twenty. The story goes that director Don Seigel and screenwriter Stirling Silliphant wanted to focus exclusively on Dancer and Julian, but were pressured by the bigwigs at Columbia to include the police procedural elements that the series was famous for. Frankly it shows. Dancer and Julian far are away the most compelling characters in the film, something that is reflected in the fact that it’s actors Wallach and Keith who get star billing here, with Meyer and Reed relegated to supporting player status, despite Reed’s co-starring role in the series. Where Quine and Asher are largely two-dimensional detectives, Dancer and Julian are fully fleshed-out characters whose personality traits suggest intriguing back stories for both. When we first meet them sitting on a plane as it makes its approach to San Francisco, for example, Dancer is studying English grammar under Julian’s guidance in pursuit of personal advancement, and we later discover that Julian is gleefully compiling a collection of the final words spoken by the people that Dancer kills in the course of his endeavours.

Once they’ve landed and set themselves up they are joined by Sandy McLain (Richard Jaeckel), a blonde-haired dipsomaniac driver whom Julian initially distrusts and later has cause to caution for his ill-chosen words and berate for his drinking. In perhaps his most telling exchange, he says to Julian of Dancer, “I knew a guy like him once,” to which Julian coldly replies, “No, you didn’t. There’s never been a guy like Dancer. He’s a wonderful, pure pathological study. A psychopath with no inhibitions.” We get to see that claim backed up when the one of the couriers foolishly tries to blackmail him and when the unfortunate houseboy of second carrier refuses to hand over the item in which the goods are hidden. As a result, by the time he moves on to Dorothy Bradshaw (Mary LaRoche) and her young daughter Cindy (Cheryl Callaway), we’ve been given good reason to fear what he might do to them if things don’t go exactly as planned.

This is Don Siegel warming up for his dynamite 1964 remake of The Killers in the city in which he would later make one of the most iconic of all cinematic police stories, Dirty Harry. He makes fabulous use of city locations in a way that gives the story a real sense of place and scale, and works with cinematographer Hal Mohr and editor Al Green – both industry veterans – to drive the story forward at a relentless pace. Tension is effectively built when required and a climactic vehicle dash across the city, despite a few back projection shots (one of which is actually quite hair-raising), is thrilling precisely because it involves real cars driving at dangerous speeds though actual locations.

The performances of the good guys are functional at best and intermittently a little stilted in the case of Emile Meyer’s line delivery as Quine, but compensation aplenty is provided elsewhere. As Dancer, then relative newcomer Eli Wallach oozes menace with just a look or a line of dialogue, and when later pushed too far his momentary mania is genuinely alarming and its consequences shocking for a film of its day. A claim made in one of the commentary tracks that this performance has a Joe Pesci quality about it is absolutely spot-on. As his older mentor Julian, meanwhile, Robert Keith makes for a compellingly quirky sidekick, and as it was with the killers played by Stephen McHattie and Greg Bryk in David Cronenberg’s A History of Violence, you can’t help wondering how these two first met and what terrible misadventures brought them to this defining point in their careers. Richard Jaeckel also makes an impression as their driver Sandy, who can certainly handle a car when required but fails to see his alcoholism for what it is and really needs to learn when to keep his mouth shut. I’ll also give a shout out to Robert Bailey as the man sent to meet Dancer at the port and identify the couriers as they leave their ship, and in a small but crucial role, Vaughn Taylor’s use of silent stares is as intimidating as anything even Dancer can put into words.

This really is a belting, hard-boiled crime thriller, and despite the lead detectives’ lack of personality and crime-solving smarts (the case only really progresses thanks to a couple of keenly observant patrolmen) and an overlong line-up sequence that only appears to have been included to justify the title, it has so much to recommend it that I wasn’t in the least bothered by what I can’t even fairly categorise as flaws. There are a number of standout scenes, including three increasingly tense confrontations between Dancer and the unwitting drug couriers (one of which is ripe for subtextual analysis), and a superb build-up to the aforementioned car chase set in the vast expanse of the Sutro Museum. It’s possibly the finest film in a cracking collection, one that drags noir out of the shadows and into the glare of daylight without diluting what makes this delicious subset of the crime movie genre so compelling and endurable to this day.

Part 2: Tech Specs, Special Features and Summary >>

|