|

– Part 1: The Films –

Fu Manchu is one of those names that even those who’ve never read any of Sax Rohmer’s novels or seen any of the film adaptations seem to be aware of. To some degree that includes me, as despite having seen at least a couple of the films in this very box set as a young teen, all these years later and faced with covering all five of the films made between 1965 and 1969 starring the infamous Chinese supervillain, I couldn’t remember any specifics about them or even which ones I’d seen. In the years that followed, the opportunity to revisit them and catch up with the ones I’d missed never presented itself, and I’ve since become just a little more sensitive to the practice of casting Caucasian actors in ethnic roles.

Ah yes, the casting. I may be wrong on this (I just checked, and apparently I’m not), but as far as I’m aware none of the film adaptations of Rohmer’s stories have cast a Chinese actor as the most famous of all fictional Chinese villains. Boris Karloff played him, Walter Orland played him and Christopher Lee played him, all of whom are about as Chinese as Justin Timberlake. Of course, the casting of Caucasian actors in ethnic roles was once standard practice and would not have raised anything like as many eyebrows as it would today. If you wanted to sell a film you usually needed a name actor, and back in the day there were precious few if any non-Caucasian actors famous enough to headline a movie, which in itself is a glum reflection on the racial attitudes of years past.

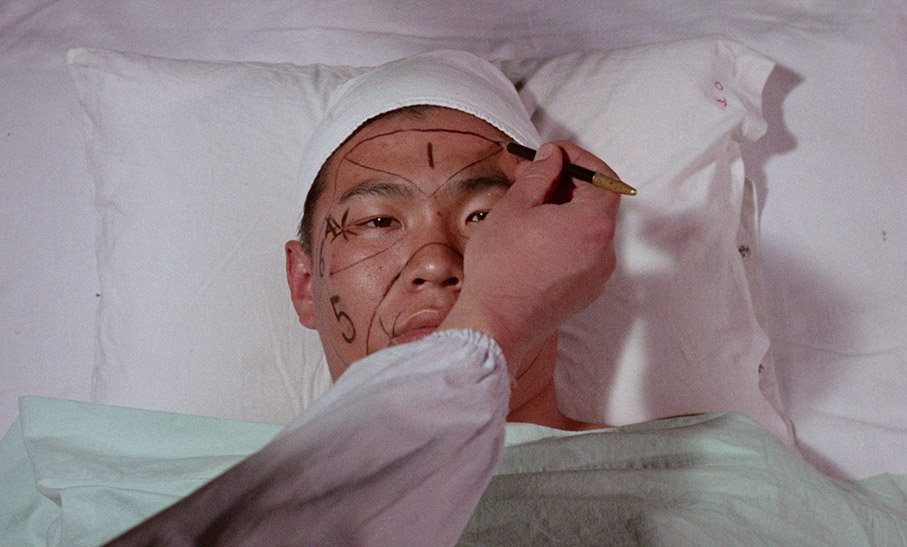

All five films in this set were produced by Harry Alan Towers, who also wrote the screenplays under the pseudonym Peter Welbeck. Fu Manchu is played in each by Christopher Lee, whose towering height and very English voice worked against the notion that he was in any way Chinese, while Lee himself complained that the oriental epicanthic folds he had to wear severely restricted his ability to express himself facially. But Lee was also a commanding and imposing screen presence and brought an authority to the role that made it easy to believe that Fu Manchu really was a master villain capable of marshalling considerable resources, and that he could torture or kill just about anyone without blinking if he thought it would further his cause in even the smallest way. It’s worth noting that he’d laid the groundwork for his performance here four years earlier in Hammer’s The Terror of the Tongs, in which he played master Chinese villain Chung King, a role that absolutely prefigures his portrayal of Fu Manchu, right down to the makeup and narrow drooping moustache. But there’s also a sense that a few things were taken on board in the years that separated that film from the ones here, particularly when it came to the casting of supporting roles. Where Terror of the Tongs was littered with Caucasian actors unconvincingly pretending to be Chinese, here Chinese supporting characters tend to be played by oriental actors. And while a few of Fu Manchu’s henchmen are not remotely Chinese, I don’t see that as a problem when the films in question are set in locations such as London or Istanbul, where it’s easy to believe that some of Fu Manchu’s goons could well have been recruited from the local criminal fraternity.

It’s long been acknowledged that Fu Manchu’s Scotland Yard nemesis Nayland Smith and his close friend Dr. Petrie are modelled in part on Sherlock Holmes and Doctor Watson, while the influence of the hugely successful James Bond franchise is evident not just in Fu Manchu’s “Rule the World” supervillain status and fondness for elaborate and gadget-driven schemes, but in the action, pace and scope of the first film in the series, The Face of Fu Manchu. Not everyone is in agreement on this, but for me and a fair few others, after a cracking start the films became a victim to the law of diminishing returns, though this can be put down partly to the fact that each is effectively a variation on the same theme in a different location. In each film a presumed dead but very much alive Fu Manchu devises a new scheme to threaten world safety or stability and provides a demonstration of his new power, and Nayland Smith and/or his friends and colleagues take on the job of tracking him down and foiling his plans. It always eventually goes tits-up and each film ends with a big explosion and an assurance from the unseen Fu Manchu that “The world shall hear from me again.”

Although Fu Manchu is played by Lee in all five films, Nayland Smith is portrayed by a total of three actors over the course of a series that saw a similar spread of directors. The only other actors apart from Lee to appear in all five were Howard Marion Crawford as Dr. Petrie and Tsai Chin as Fu Manchu’s cooly sadistic daughter Lin Tang – Chin later found more widespread fame as Auntie Lindo in Wayne Wang’s The Joy Luck Club and is currently attracting some serious praise for the title role in Sasie Sealy’s debut feature, Lucky Grandma. The exact year in which the films are set is never specified, but the smart money is on the mid-1920s, which despite a few obvious anachronisms is rather nicely recreated, and does give a slight whiff of Hammer to films that are sometimes incorrectly credited as the work of that studio. It’s not hard to see why.

As I’m already behind on this review due to an absolute slew of work in my day job, I initially pledged to keep the reviews of the films themselves as tight as possible in order to give the absolute mountain of special features due consideration, but as ever I got a little carried away, which I doubt will remotely surprise any site regulars.

And so to the films, starting with what appears to be many people’s (though definitely not everybody’s) favourite. It was certainly mine.

| THE FACE OF FU MANCHU (1965) |

|

The first of Harry Alan Towers’ Fu Manchu films begins how you might expect the last in the series to end. In a regal-looking courtyard in early twentieth century China, British army officer Nayland Smith (Nigel Green) bears witness as a government official oversees the execution of notorious criminal mastermind Fu Manchu, who is led out to the courtyard, where he lays his neck on a chopping block and is decapitated by a burly executioner. Hmm, not much of a plot, was it? But instead of the final credits we get the opening titles. If I were not fully aware that there were another four films in the series, I would likely have suspected that this really was how the film concludes and that the journey to this point was now going to unfold in flashback. But knowing that’s not the case it quickly becomes obvious that Fu Manchu can’t be dead. Yet we saw him executed. His arch-enemy Nayland Smith saw him executed and he knows his face better than almost anyone. And that was Christopher Lee, no question, and that’s who Fu Manchu is played by. So what gives? You’ll have to watch the film to get an answer to that one.

Back in London an unspecified time later, Smith is troubled by the news of a series of kidnappings of renowned scientists, the latest of which has resulted in the disappearance of a celebrated biochemist named Professor Müller (Walter Rilla) and the murder of his manservant in a manner unique to Fu Manchu’s henchmen. Smith becomes convinced that Fu Manchu is alive, and after meeting Müller’s assistant Carl Jannsen (Joachim Fuchsberger) and outlining his suspicions, he teams up with him in an effort to uncover where Fu Manchu is hiding and what his latest dastardly plan is.

Nowhere in the series would the pitch “James Bond meets Sherlock Holmes” be more appropriate than it is in this belting opener, one whose ambition and scope none of the sequels were quite able to emulate. For a start it has the series’ best Nayland Smith in the shape of the ever-excellent Nigel Green, who takes the role as seriously as he doubtless would a lead in a Shakespeare play and from the off makes Smith a convincing force of conviction and determination. When Smith says he’s going to prove Fu Manchu is still alive and track him down you believe he’ll stop at nothing to do it. Mind you, his methods can sometimes be called into question. As an officer of the law I have little doubt he could gain legal access to Professor Müller’s lab and poke around for clues, but instead he breaks in at night and ends up in an almighty brawl with Jannsen, one in which Smith’s identity is kept hidden from the audience until the inevitable light is switched on by Müller’s daughter Maria (Karin Dor). It’s a bloody good fight, though, one whose energy and physicality is up there with the best punch-ups from the early Bond films. Ah, that connection again…

Maria, it turns out, has information that helps to confirm Smith’s suspicions about Fu Manchu, but the film itself intriguingly refuses to do so conclusively until almost a third of the way in, focussing instead on Smith’s investigations and the mystery of what his nemesis might be up to. Indeed, we meet Fu Manchu’s daughter Lin Tang and his German business associate, Hanumon (Peter Mosbacher) before we meet the big man face-to-face. Fu Manchu, meanwhile, is quick to establish how ruthless he can be by executing one of his female guards for attempting to help Müller by throwing her in a tank, filling it with water from the Thames above and forcing his captives to watch her drown. And this is after Lin Tang was almost licking her lips at the prospect of taking a whip to the woman’s naked back, then reacting to her father’s interruption with visible disappointment.

The search for Fu Manchu’s London hideout is peppered with vigorous action, including a couple of decent brawls and what feels like a city-centre car chase, one that is all the more impressive for the level of period background detail in even the briefest of shots (though don’t look too hard at the parked cars in the distance when Smith and Petrie start their chase of Fu Manchu and Lin Tang). A centrepiece scene, in which what seems like half of Scotland Yard is dispatched to The Museum of Oriental Studies to protect papers that are crucial to Fu Manchu’s plans, may be so littered with assurances of its vault’s security that you just know it’ll be somehow breached, but it’s still a fun sequence and has a small roles for the ever-lovely James Robertson Justice as the museum curator and a typically fine Joe Lynch as the vault custodian. It is here, however, that Petrie makes his dumbest move by loudly reading out out an address that absolutely must not fall into Fu Manchu’s hands in a public area of the museum just feet from a woman who has gone to great lengths to hide her face. I think I actually slapped my forehead at this.

Don Sharp’s tight and energetic direction makes great use of his Ireland locations and ensures that the pace rarely drops, and the script by Harry Alan Towers (writing as Peter Welbeck) has its share of neat twists, including a demonstration of Fu Manchu’s newly acquired power that I genuinely did not expect to see carried out. The sequence itself is chillingly handled and in a manner that recalls an earlier British science fiction film of note (I’m trying to avoid giving too much away here), while the scale, speed and implications of what unfolds are disturbing enough for me to question the film’s family-friendly original UK certification. There’s an early use of karate as a fighting style, and while we have to live with the ‘Yellow Peril’ casting of the Chinese as the villains of the piece, it’s nice to see German characters played by German actors rather than English performers wearing fake German accents. That the film was a co-production between the UK and West Germany is, of course, purely coincidental.

| THE BRIDES OF FU MANCHU (1966) |

|

There’s no ambiguity about Fu Manchu’s survival in this 1966 sequel, which opens with a man being led blindfolded down a dark stone corridor into what looks like an Ancient Egyptian throne room, where a number of frightened western women with 1960s hairstyles are chained to stone pillars and Fu Manchu and Lin Tang are holding court. The blindfolded man’s name is Jules Merlin (Rupert Davies) and his daughter Michel (Carole Gray) is one of the female captives, all of whom have been kidnapped to persuade their fathers – all eminent scientific or industrial experts in their home countries – to assist Fu Manchu with his latest devilish plan. The disappearance of these young women is something Nayland Smith (Douglas Wilmer) becomes intrigued by during the course of a bit of expositional chat with the initially dismissive Petrie. It turns out nobody’s been nabbed in England yet, something Smith reflects on by foolhardily saying to Petrie, “I find myself wishing they almost would try it here.” Then you’ll show them, eh, Smith?

It turns out he doesn’t have to, as when a German research chemist named Franz Baumer (Heinz Drache) is attacked on the Thames Embankment and an attempt is made to kidnap his fiancé, Marie Lentz (Marie Versini), Baumer fights his assailants off so effectively that one of them ends up dead. Despite being a victim in this assault, Baumer is arrested, while the discovery of a Tibetan prayer scarf on the body of the dead man alerts Nathan Smith to the fact that Fu Manchu’s men were likely behind it. It turns out that Marie’s father is famed engineer Otto Lentz (Joseph Fürst) and is supposed to be in Germany, while Marie now works as a nurse at a London hospital and is already back at work. She’s also surprisingly chipper for a woman who was recently attacked and knocked unconscious and whose boyfriend is in the clink facing a possible manslaughter charge. Smith and Petrie visit Baumer in prison and on being told where Marie is working they head straight there, but Fu Manchu’s men are ahead of them and attempt a second kidnap, which is foiled by Smith and Petrie’s timely arrival. In an unexpected twist that has a further twist later, Smith’s pursuit of the fleeing men is hampered when he is knocked to the floor by Marie’s friend Nikki Sheldon (Harald Leipnitz) after he mistakes Smith for one of the kidnappers.

Even more so than the first film there is an international flavour to the principal cast, thanks to the presence not just of German actors Heinz Drache and Harald Leipnitz (yep, this is another UK-West Germany co-production), but Austrian Joseph Fürst, Pakistani actor Salmaan Peerzada as a young Arab servant who the imprisoned brides of the title, and French actors Marie Versini and Roger Hanin. Hanin plays Smith’s friend and French counterpart, Inspector Pierre Grimaldi, a man whose interest in the case prompts him to ignore orders from his superiors to drop it and instead hop over to England to lend his assistance, where he proves to be a wily and dedicated investigator. You see how much better it all works when we Europeans pool our resources and work together? The icing on the cake is the always wonderful Burt Kwouk, who as Fu Manchu’s chief engineer, Feng, not only gets almost as much dialogue as his boss but appears to be the one person in whom Fu Manchu has faith and treats more like a comrade rather than an order-following minion.

Once again Don Sharp is in the director’s chair, and while this second film lacks the sense of scale of its forebear, it still moves at a lick and reworks many elements of the previous film to entertaining effect. Here Fu Manchu’s method of demonstrating his ruthlessness involves a snake pit into which victims are dropped and sealed, and the deadly gas of the first film has been traded in for destructive radio waves, and the very public exhibition of their power once again has dire consequences, this time involving a really nicely handled twist that I neither saw coming nor felt remotely cheated by. And while often more enclosed than its predecessor, the film still boasts some good location work and plenty of lively action, including a car chase, an aerial bombing attack, a handful of fights and a briskly staged third attempt to kidnap Marie when she's tricked into dropping her guard and spending an evening at the theatre.

Although not as convincingly driven as Richard Green, Douglas Wilmer still makes for a suitably earnest Nayland Smith and is not above throwing a few punches when required, and Lee is on his usual fine form as Fu Manchu, but my favourite characters here were in the supporting cast. As Inspector Grimaldi, Roger Hanin creates an instantly likeable character who never plays second fiddle to Smith and is allowed to conduct his own fruitful investigations and punch his way out of a fix without assistance from Smith. There’s a nicely judged turn from Kenneth Fortescue as young and convincingly dedicated detective Sergeant Spicer, and I took an instantly liking to Salmaan Peerzada as Abdul, the servant who risks his life to help Fu Manchu’s prisoners, and found myself becoming more concerned for his safety than I was for any of the people he assists.

There is one short sequence that did make me wince, however, when Fu Manchu explains to Lin Tang (and thus the audience) how a lever should be used and the potentially dire consequences of pushing it too far (seriously, why even build that function into it?), a painfully clunky bit of expositional foreshadowing for a moment that, when it arrives, will surely surprise nobody. Elsewhere the film is a little smarter with its telegraphing, providing confirmation of a suspicion I developed about one character just minutes after I’d done so, thus allowing me to momentarily feel I was smarter than the filmmakers before reminding me that they knew just what they were doing all along. And although the film plays to conventions of the time by making attractive and scantily clad women the prisoners of gruff and manipulative men (and one coldly sadistic woman, of course), it scores some points when the women break free by having them fight their captors every bit as vigorously as their male counterparts.

| THE VENGEANCE OF FU MANCHU (1967) |

|

Having cheated death again, Fu Manchu returns to his ancestral home in China, where he is greeted as a ruler and begins plotting vengeance against his nemesis, Nayland Smith, as part of a plan to become the leader of the world’s organised criminal gangs. To this end he blocks the only roadway into the region and sends word out that it was a result of an earthquake (one that nobody else could have felt), and has his minions kidnap surgeon Dr. Lieberson (Wolfgang Kieling) and his daughter Maria (Suzanne Roquette). He then tortures Maria to force Lieberson to transform a hypnotised subject into an exact facsimile of Nayland Smith, whom he uses to replace the real one with the aim of having him commit murder and be publicly disgraced and executed for the crime. The real Smith, meanwhile, he has transported to the castle, where he offers him the choice of joining his organisation as a servant or dying as soon as his doppelganger is executed.

OK, where do I start with a plan that even by Fu Manchu’s standards is batshit preposterous? First up, the very notion that in the 1920s, organised crime syndicates the world over would willingly submit to the rule of a foreign criminal mastermind they’d only be aware of through third-hand tales is about as easy to swallow as an uncut pineapple. The proposal also relies on the fantasy premise that all of the organised crime in each country was being committed by a single unified organisation. I seem to remember that in roaring twenties America, gangs were shooting each other in the streets. Hmm. Then we have Fu Manchu’s claim that once he discredits the leaders of the world’s major crime-fighting organisations, criminals would be able to rise up and take control of the countries in question. Clearly he’s never encountered the notion of appointing someone equally well qualified to a post if it suddenly becomes vacant for any reason, and the idea that without Nathan Smith in charge the rest of Scotland Yard would run around like headless chickens and suddenly be stripped of their ability to fight crime is comically absurd. Then we have the substitute Nathan Smith, and I may not be a plastic surgeon, but if you’re going to replace a tall, slim, middle-aged. angular-faced and large-chinned Caucasian with a convincing imposter, then I’m guessing it would be a good idea to a select a subject who at least shares his physical characteristics, and not a younger, round-faced Chinese gentleman who looks absolutely nothing like him. This guy wouldn’t need his face remodelling, he’d need a new skeleton and skin. I’m not exaggerating here – when we later see the transformed man’s hands in close-up they are clearly not the ones he had before the op. Just how much reconstructive surgery did Leiberson perform in the 48 hours he was given to complete it? And then there’s the business of Smith’s kidnap and replacement. After having his plans for world domination fooled twice by Smith, who was already his greatest foe at the start of the first film, you’re telling me Fu Manchu could just dispatch a handful of his men to kidnap Smith and replace him with his double and it would all go like clockwork? Wouldn’t that suggest he could have found and killed Smith at any time previously? So why didn’t he?

OK, hang on, I’m going off on one here, but I do have my reasons. For me to fully engage with a film that plays fast and loose with reality I need to be able to suspend my disbelief, and so far in the series that’s something I had little problem doing. In the first film the idea of using a lethal airborne poison as a weapon of mass destruction has its roots in the very real world of chemical warfare, while in the second the more fanciful notion of destructive radio waves uncannily predicts current endeavours to develop microwave-based directed-energy weapons. But nothing about the plan in Vengeance feels remotely plausible, and at seemingly every step I found myself blurting out, “yeah, but…” at the screen. This disassociation from reality is further emphasised by Rudy, the representative of American criminal interests who is dispatched to meet with Fu Manchu. Visually, he plays to American bigshot stereotypes of years past by wearing a ten-gallon hat and smoking big cigars, but when he speaks he does so with a distinctly German accent. Given that he is played by German actor Horst Frank (yep, another co-production) this is not that surprising, but it makes little sense in the context of who he is supposed to be and whom he represents.

Early warning signs that things were changing here come during the opening titles, when the writers of two songs are credited. Songs? In a Fu Manchu movie? Are you kidding me? They turn out to be diegetic rather than musical numbers, performed in what one character describes as the hottest bar in Shanghai (there are hints that this otherwise bemusing reputation is down to its trade in what I can only assume are largely invisible sex workers) by Rudy’s girlfriend Ingrid (Maria Rohm), who takes a job singing in the bar for unspecified reasons and ends up falling for Kurt (Peter Carsten), the (German) man who runs it. It’s been suggested that Rohm’s casting and her performance of these songs (which it turns out were dubbed by singer Samantha Jones) came about because she was writer-producer Harry Alan Towers’ girlfriend at the time. That’s the only explanation that makes sense to me.

If it seems like I’m hating on a film that Jonathan Rigby and Kevin Lyons regard as the best of the series (a revelation I’ll admit caused me to choke on my coffee), that’s genuinely not my intention. Yet after enjoying the hell out of the first two movies, I struggled to engage with this one on anything like the same level and found it a bit too easy to spot why, and I haven’t finished griping yet. Scenes that had the potential to be intriguing – the amusingly fanciful notion that Nayland Smith was one of the founders of Interpol is a good example – lack dramatic and cinematic spark, and I lost count of the number of time-advancing flip-transitions used in the fake Smith's trial, which make it look suspiciously like a scene that was considerably longer in the first cut and was hastily shortened for the release print. The action, when it comes, is just not up to that of the film’s immediate predecessors, with one notable exception, though if the commentary is to be believed (and Rigby and Lyons know their stuff), there could have been another. Allow me to clarify. The film was shot in Hong Kong at Shaw Brothers studios just as production there was switching primarily to the newly popular (on home turf at least) martial arts movies, yet for the most part the fights and brawls in this film are on the shabby side, lots of flailing around and pushing and forceless punches. But when Shanghai’s Inspector Ramos (Tony Ferrer) is attacked in the street by some of Fu Manchu’s goons, the resulting unarmed combat battle is an absolute cracker, with Ramos dishing out some furious martial arts hits and kicks, in the process completely convincing me that he could defend himself against any number of violent villains if required. The thing is, apparently there was another full-on martial arts battle shot for inclusion, but this was removed by editor Allan Morrison because he thought all the grunting and yelling that accompanied it was silly and would just provoke laughter. Six years later, Jeong Chang-hwa’s King Boxer (aka Five Fingers of Death) would hit western cinemas and kick off a sensation that this film could so easily have been a precursor of.

And yet the film is still enjoyable and has a number of very real pleasures. The violence has been upped here (even if we cut away from it at some climactic moments) and the overall tone has shifted away from the adventure sweep of its predecessors and more towards more Hammer-style horror. The medical silliness of the remodelling and body-swap aside, the notion of someone you know being replaced with an inexpressive pre-programmed killer has echoes of both Invasion of the Body Snatchers and The Manchurian Candidate, and Douglas Wilmer’s lack of emotion as the doppelganger Smith is actually quite creepy. Christopher Lee and Tsai Chin had their characters nailed by this point, and with the real Smith sidelined for much of the film, it’s down to Howard Marion-Crawford as Petrie and Noel Trevarthen as FBI agent Mark Weston to move their side of the story forward, and while not exactly a dynamic duo they do a sound enough job. There’s no question that director Jeremy Summers makes attractive use of some excellent locations, but I did miss Don Sharp’s eye for camera placement and smooth editing continuity, though it is worth noting this film’s immediate predecessor was also edited by Allan Morrison – you can only work with the material you’ve got, I guess.

I was never bored by The Vengeance of Fu Manchu but never as gripped by it as I was by the first two films, and the daffiness of some elements made it hard for me to take it that seriously, not that this probably matters in a series about the exploits of a Chinese supervillain intent on world domination. This does result in an odd contradiction, however, as the move towards a more horror-inflected tone coupled with implausible plot elements make it simultaneously the darkest and daftest film in the series so far. That said, it at least still feels like a Fu Manchu film and very much part of the series. Whereas…

| THE BLOOD OF FU MANCHU (1968) |

|

For all The Blood of Fu Manchu’s peculiarities – and I’ll be getting to them – it certainly gets off to an intriguing start, albeit thanks in part to real-world events that were not even on the horizon when it was made. It opens with a line of women being led through a jungle, chained together with white cloth hoods over their heads, an image that today has disturbing associations, that of Taliban kidnap victims being led to a secret hideout or even their execution. The women are finally led into cave that has become Fu Manchu’s latest lair, and for me this tells an unspoken story about Fu Manchu’s fate and his delusions of grandeur. Where once he commanded an army in a sizeable underground headquarters or a grand castle, now he is hiding away in the sort of hovel that a desperate hermit might inhabit, still dressed like an emperor and still making plans to conquer the world, but looking ever more like an egomaniacal failure who just won’t face up to the fact that his time is up. Remind you of anyone?

He still holds the mother of all grudges against Nayland Smith, and once again has managed to find a way of intermingling personal vengeance with the business of world domination. His plan this time requires killing a whole slew of prominent people, but just having his men run up and stab them would be way too straightforward for someone with a taste the exotic and supremely unlikely methods of murder. That said, the plan is not without its merits, even if its biology is, shall we say, a little suspect. The reason Fu Manchu has had these attractive young women kidnapped and imprisoned is to infect them with a poison that they can then pass on to another by kissing them on the lips, which causes the victim to immediately go blind and a few weeks later to die. What’s smart about this is the notion that few men of any station – and particularly those who have been corrupted by power – would be able to resist the charms of an attractive woman, and as a result the man targeted would likely let down his guard for long enough for the woman in question to plant her lips on his. It doesn’t matter if he is shocked by her behaviour and pushes her off, as by then the deed will have been done and he'll die in a few days. Neat. There’s just one thing – the poison is passed into the bloodstream of these unwilling female assassins by holding a lethally venomous snake against their skin until it bites them, and they are apparently immune to its venom simply because they are women. Excuse me? There is a hint that they are somehow immunised against the poison, but this process seems to consist of nothing more than a few ritualistic words spoken by Lin Tang before the snake passes the world’s most potent toxin into their bodies. Sorry, no sale.

Unsurprisingly, Nayland Smith is first on Fu Manchu’s worldwide list of targets. What did catch me out is that instead of sussing that something is up when a hypnotised woman shows up at his door, he is quickly kissed by her and stricken immediately blind. This effectively takes him out of the running as a foe for Fu Manchu for most of the film, at least until his predictable but still “Oh come on!” reappearance in the final few minutes. Indeed, apart from a few sequences in which he sits staring ahead and looking distressed and helpless, Smith is consigned to a small supporting role here, which gives Douglas Wilmer’s replacement Richard Greene precious little to do in his first stab at the part. More baffling is that it’s a similar story for Fu Manchu himself, who despite driving the plot and having his name in the title, only makes occasional appearances in a film that seems to be less about Fu Manchu than Carl Jansen – Dr. Müller’s assistant from the first film, who is now working as an operative for Smith and is played here by Götz George – and notorious local bandit, Sancho Lopez (Ricardo Palacios).

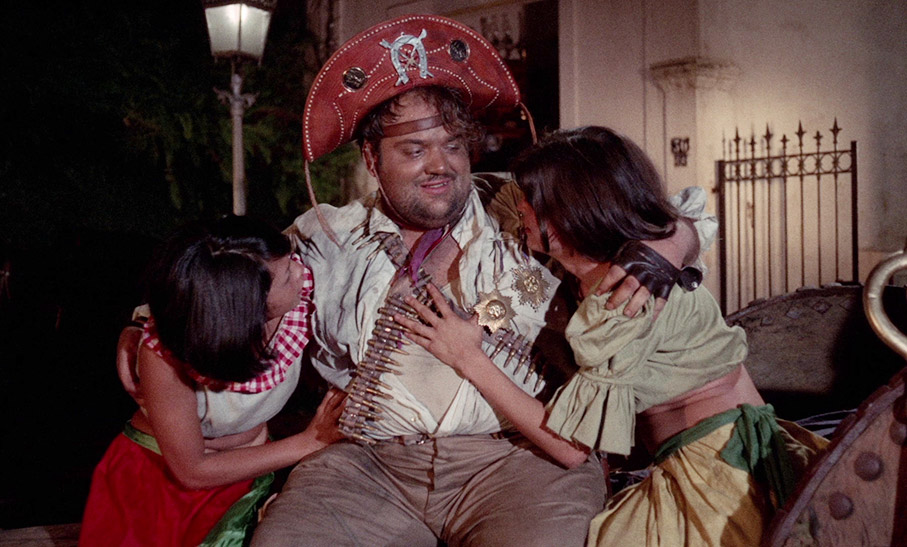

Ah yes, Sancho Lopez. Cast your mind back to the days when a Mexican bandit leader was portrayed in films as an overweight slob who rarely shaved or washed his clothes, dribbled wine down his chin, killed at will with an evil cackle and ogled at women who either screamed when he grabbed them or clambered all over him and laughed at the pleasure of being pawed by such a gargoyle. This should give you a fairly accurate picture of Señor Lopez. Combine this with cinematography that’s littered with odd angles and zoom shots, plus some awkward post-dubbing of actors who clearly weren’t delivering their lines in English, and it starts to feel like a low-budget spaghetti western in which Fu Manchu makes a guest appearance.

By this time, director Jess (aka Jesús) Franco already had a bit of a rep for lacing exploitation films with stylistic touches, and here seems to be experimenting with ideas that don’t always come off. A prime example of this involves a fight to the death between Karl and one of Fu Manchu’s men, which is captured in a single long lens shot looking through foliage, which has the effect of obscuring much of what’s happening and making it look less like a fight than two lovers rolling around on the jungle floor. The use to which Daniel White’s score is put is also inconsistent, being absent from scenes that seem to be crying out for music but blasting out when silence or something more subtle is called for. For the first two thirds it’s certainly easy enough to follow, in part because some scenes play out at an unhurried pace, while Franco’s sleazier leanings result in more nudity here than in the first three films, some of which was originally cut for the film’s UK release. There’s also occasionally an odd sense that the film pretending its immediate predecessor didn’t exist, with Smith having lost the grey hair he sported in Vengeance and his original Chinese maid, Lotus (again played by Francesca Tu), back in his service after the loss of her replacement Jasmin (Mona Chong) in the previous film.

Later, things get increasingly confusing, with disorientating narrative jumps and some anachonistic deleted material from Franco’s 1968 The Girl From Rio featuring Shirley Eaton (who apparently knew nothing about this) cropping up, which requires some mental gymnastics on the part of the audience to link to the footage that surrounds it. Having said that, this sequence does turn the film’s notion of a woman being transformed into a tool of destruction by a powerful man momentarily on its head, as for a short while they come across more as righteous punishers of the sins of lascivious men. I also can’t help thinking that the notion of a lethal kiss could form the basis of a whole essay on toxic relationships and Freudian theories regarding the link between sex and death.

By the finale I was struggling with a whole slew of questions (the way Lopez escapes from his cell had me pointing at the screen with my lower jaw hanging open in disbelief) and wondering seriously if the production ran out of time and money and had to wrap things up with what they had in a hurry to get the film into cinemas. It’s a genuinely peculiar work that’s not without its charms and effective moments, and were it not part of a franchise whose title character here plays second fiddle to altogether less interesting beings, I have a feeling it could have been developed into something more quirkily entertaining than it is. I didn’t dislike it, but there’s a real sense here that, like Fu Manchu’s ambitions for world domination, the series is starting to really lose its way.

| THE CASTLE OF FU MANCHU (1969) |

|

What the f...?

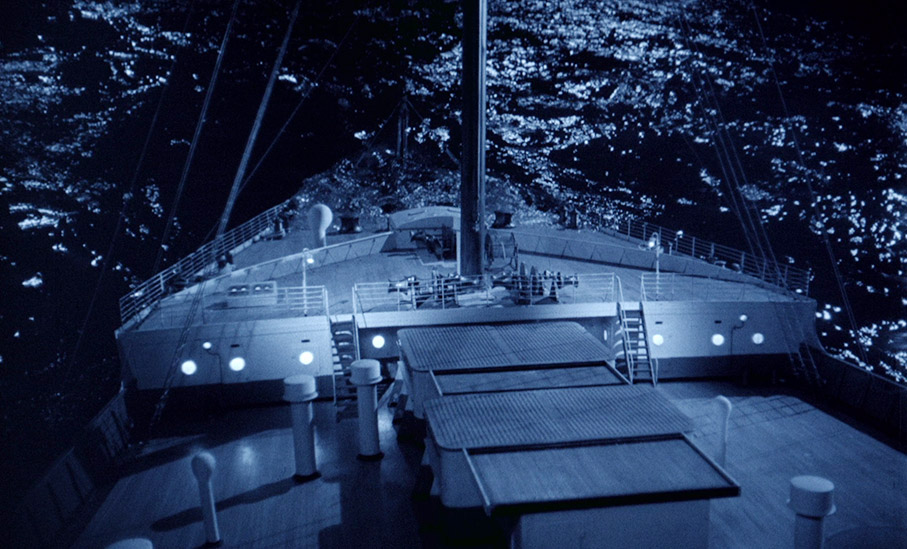

OK, had you seen this fifth and final film in the series back when it finally made its way into UK cinemas in 1972, particularly if you’d not seen its predecessors and were not bothered by peculiar visual quirks, then maybe, just maybe, you’d have no problem with the opening scene that is dished up here. If you’ve just watched the other films in this box set, however, and know your British movies, that’s unlikely to be the case. I’d like to say you’ve not seen anything like it before, but that genuinely couldn’t be further from the truth. In it, Fu Manchu commands his men as they energetically twiddle knobs and dials on a wall and desk full of electronic equipment. The purpose of their activity is revealed when the distantly located cruise liner that is their target runs into an iceberg and sinks. As the ship sinks, things go horribly wrong in Fu Manchu’s laboratory, but he and Lin Tang are able to flee before it explodes. If this sounds more like the climax of a movie than an opening scene, well, that’s because it is. Actually, it’s the climax of two movies. The laboratory stuff has been lifted from the finale of The Brides of Fu Manchu, complete with a panicking Burt Kwouk and that terrible “that lever should only be moved to this point” bit of foreshadowing. Making matters worse is the footage of the ship running into an iceberg has been poached from the finest of all Titanic movies, A Night to Remember. But wait, wasn’t that shot in black-and-white? Indeed it was, which director Jess Franco – for it is he again – attempts to disguise by giving the whole thing a light blue tint. See, it’s in colour now! The opening scene thus consists of repurposed colour footage from the climax of an earlier Fu Manchu film intercut with tinted monochrome footage from the climax of a celebrated British based-on-fact drama. Seamless!

Go back to this scene a second time with the knowledge of what follows and it also makes no contextual sense. Fu Manchu has kidnapped a scientist named Professor Heracles (Gustavo Re), who has developed a formula to make water do something-or-other. Freeze large swathes of it, I think, but the only other demonstration of it we see knocks a hole in a hydroelectric dam through which regular water then flows, so it’s hard to be sure. I’m not sure the filmmakers were that certain themselves, and the footage of the dam’s destruction was nicked from a movie titled Campbell’s Kingdom – the colour and film grain are different here and if you look carefully you’ll be able to spot Dirk Bogarde and Stanley Baker running away. Either way, as far as I can see this formula has to be dropped into the water for it to be affected, yet in this opening scene it appears to be directed by radio waves – hardly surprising given the film the colour footage was lifted from – which produce a single iceberg that the ship was unfortunate enough to be heading straight towards. Precision-directed, iceberg-creating radio waves then. It then becomes clear that Heracles is in failing health due to a heart condition and has yet to reveal the formula that Fu Manchu sent by radio waves in the opening sequence. Eh? What? My head hurts.

The Castle of Fu Manchu has a bit of a reputation, one reflected in its 2.9 IMDb user score and its 10% rating on Rotten Tomatoes at the time of writing, and it is a bit of a mess. The one thing you can say in favour of that opening is that it at least gives you a flavour of what’s to come, at least in regards to storytelling logic. Take the alliance Fu Manchu and Lin Tang form with Istanbul opium dealer Omar Pasha (José Manuel Martín). They team up with this guy so that he can have his goons clear a way into the Governor’s castle and allow Fu Manchu’s black-clad soldiers to slide in and take control of the huge supply of opium being stored there. Yet all Pasha’s people are required to do is get the guards to open the main gate and then kill them, after which Fu Manchu’s men run in and slaughter everyone else. Given that the Fu Manchu boys are so agile and kill silently with swords, it seems likely they could have murdered the guards themselves and hopped over the walls that sit either site of the gate. They’re not that high, especially for would-be ninjas. And this invasion succeds because the guards and the governor himself are caught completely by surprise. Seriously? Are they deaf? Pasha’s people killed the main gate guards with a machine gun. I would think this could be heard all across the city. And Pasha's hard-as-nails female chief operative Lisa (Rosalba Neri) fired a flare into the sky immediately afterwards to alert Fu Manchu's men. I guess they're a little short-sighted too. Then, having taken control of the castle, Fu Manchu orders his soldiers to kill their new partners, which results in a slew of his own people being shot and Lisa's apprehension, which makes an instant enemy of the most powerful drug lord in the city. Mind you, as dumb decisions go, the one to kidnap the ailing Heracles’s heart specialist Dr. Curt Kessler (Günther Stoll) and his girlfriend Ingrid (Maria Perschy), seal them in coffins for transport and then place these coffins in Heracles’s cell really does take some beating. Fu Manchu has brought Kessler here to save Heracles’s life so he can get that damned formula, but when Kessler slowly wakes, raises the coffin lid and reaches out like a freshly revived vampire, the sight of this nearly gives the watching Heracles a massive coronary. There’s a real sense that years before he wheedled his way into No. 10, Dominic Cummings was doing all of Fu Manchu’s planning.

Almost nothing works as it should here, which seems particularly unfair on Richard Greene, who after being consigned to a supporting role in the previous film certainly has more to do this time around, but has little of value to work with. Although the dialogue has once again been post-dubbed, the script gives the English speakers naff all to work with and is intermittently either clumsily expositional or downright dumb. Smith suspects that Fu Manchu may well be in Istanbul, for instance, because it is one of the few places on the planet in close proximity to a huge body of water. You reckon? Last time I checked, 71% of the earth’s surface is covered with water and I can’t imagine how many hundreds of thousands of coastal towns, cities and settlements there must be across the globe. And despite being told clearly by Smith even before they depart that Anatolia is the centre for Opium production, when they arrive in Istanbul the now comically bumbling Petrie responds to the news that Omar Pasha is an opium dealer by blurting out an astonished, “Opium?!” as if the very notion is completely new to him. Pay attention, man!

It seems clear that the production ran out of money at an early stage and Franco had to make some spectacular compromises, hence the borrowing of clips from others movies and a couple of sequences that go on way longer than required and to little effect. The most 'get on with it' of these has Fu Manchu urging one of his nervous minions to ‘accelerate the process’ while he hovers excitedly over test tubes and beakers that bubble away in close-up for what seems like forever. Apparently this is a test of what he thinks is Heracles' crystalisation process (the prof hasn't given it up at this point) but it leads absolutely nowhere, despite Fu Manchu's urgent looks and the worried expression of the operative. Basically, Fu Manchu walks into the room and just watches some chemicals and dry ice bubble in beakers for a while. That’s it. There’s almost the sense that Franco asked Towers what should happen here and was told, “Oh, something scientific-looking will do.” There’s also an oddly timid approach to violence, most of which happens just off-screen, and those budget cuts seem to have rationed the production’s supply of blanks for the guns, some of which make an audible ‘bang’ but don’t seem to actually fire.

Franco’s colourful use of gelled lights may give the film a sometimes comic-book flavour, but given the subject matter I have no problem with that and it certainly gives some scenes a bit of extra visual flair. I was also initially impressed with Lisa, an agreeably tough cookie who kicks against the series’ habit of casting women as tools to be manipulated, exploited or used as leverage against their fathers by commanding the respect of the men she confidently leads into battle and being as tough and ruthless as any of them. A bit of a shame, then, that she later ends up flailing about in water like the sort of helplessly doomed damsel that earlier evidence has confirmed she most definitely is not. By this point, however, the film had lost the plot and I had ceased even trying to jot down notes for later recall. Cue the requisite exploding lair and a half-hearted claim that “The world shall here from me again.” It never did, at least not from the pen of Harry Alan Towers, and on this evidence it’s probably just as well. The story goes that when Franco screened the finished film for him, Towers turned to his director and said, “Congratulations, you’ve done what so many people have failed to do in the past. You’ve finally killed Fu Manchu.” Enough said.

Part 2: Tech Specs, Special Features and Summary >>

|