|

– Part 1: The Films –

It’s an old story by now, but I must confess to being considerably late with this one. Reviewing a box set of six films is one thing – I recently did that with Eureka’s Karloff at Columbia collection. Reviewing a six-film box set from Indicator is a different prospect, as each film comes on its own disc and is accompanied by a generous collection of special features. Reviewing one of Indicator’s Columbia Noir sets is further complicated by the likelihood that I could write several thousand words on each title and reigning myself in from potentially endless rambling is sometimes a bit of a struggle. Then, shortly after I started work on the review, I finally got the appointment I’ve been waiting for since late 2019 – just before the whole world went tits-up with the pandemic – for a procedure designed to finally alleviate the sometimes searing pain in my foot. Instead it enflamed it, and the resulting pain and associated depression blew sizeable holes my ability to focus on anything much. Two weeks later, the pain is still there, I’m still a little woozy from medication that doesn’t seem to be doing all that much except make me woozy (there are worse things to be), but I was determined to finish a review that I suspected from the start was going to run to epic length, but it’s no more than this typically superb release deserves. As before, I’ve looked at the six features first, then on page 2 have covered the technical specs and special features. It’s a long read, and some of it might be a little woolly, for which I apologise, but if you’re up for it, grab a coffee and a few snacks and settle in for Columbia Noir #3.

I’ll give points to any film that lets me to work out who a character is from what he or she says and does instead of spelling it out through up-front exposition. Take the opening scene of the oddly (but, as it turns out, appropriately) titled 1947 noir, Johnny O’Clock. A man walks into a hotel and asks if the titular Johnny lives there, and the desk clerk politely informs him that he doesn’t. The man then reels off a string of other names by which Johnny might be known and the desk clerk appears to recognise none of them, only acknowledging his existence when the visitor describes him. Already I’m certain of three things – that the man is a cop, that Johnny is involved in criminal activity of some sort and that this policeman has been after him for some time. Good start.

When we first meet Johnny, he’s being woken by his associate, Charlie (John Kellogg), who has the look of a man who would knife you for saying the wrong word, then dig through your pockets looking for anything he might be able to easily sell. We learn something about the hours that Johnny keeps when he remarks that he’d like to get a good day’s sleep, as well as that someone is fond enough of him to send him an expensive-looking watch with an engraved message of affection on its back. From the terse conversation Johnny has with Charlie over the delivery of the gift, he seems to be trying to keep this as-yet unidentified admirer at a distance. Charlie then shows Johnny a story in the paper about a gambler who was shot dead by a police detective named Chuck Blayden (Jim Bannon) whist trying to elude capture. This seems to irritate Johnny further. “Trigger-happy cop, that Blayden,” he remarks. “Always with a gun.” Again, from just that single remark we can presume that the two have a history and this is not the first time Blaydon has overstepped the mark.

When he reaches the foyer, Johnny is approached by Harriet Hobson (Nina Koch), who in the space of just a few words reveals that she has been dating and recently slapped around by Blayden, who is also confirmed to be an associate of Johnny’s. The man who questioned the desk clerk in the opening scene then steps forward and identifies himself as Inspector Koch (Lee J. Cobb), and he has a few questions that Johnny contemptuously sidesteps. Over the course of the next few minutes, we learn quite a bit more about Johnny. Simply by watching him go about his business, we discover that he manages a casino and we learn that he has an unusual approach to employee dishonesty – when he catches a dealer cheating, he doesn’t fire him as expected but instead sends him back to work on the basis that he might be replaced with someone smarter that Johnny wouldn’t be able to so easily rumble. He’s a little curt with Harriet, but when he meets with Blayden in an alley at the back of the casino, he tells him to cut out the rough stuff with her. Blayden’s parting comment comes in the form of a smiling threat. “You get in my way and I'll kill you,” he tells Johnny, who ponders on this for a few seconds before replying, “You took the words right out of my mouth.” Johnny is in his office when Nelle Marchettis (Ellen Drew), the woman who sent the watch and the one he was avoiding earlier, breezes cheerfully in. She clearly has a serious thing for Johnny and is sitting on the edge of his desk and openly flirting with him when her husband and Johnny’s long-time partner Guido Marchettis (S. Thomas Gomez) walks in. Somehow he doesn’t twig that his wife is trying to get into Johnny's pants, and possibly already has in the past. At least he doesn't yet.

All of this paints an intriguing picture of Johnny. He’s involved in criminal activity but obviously has limits and is self-confident enough of his position to be sassy with the cops and know there will be no comeback. He’s somehow attracted the attention of the boss’s wife but is also aware of the potential danger this puts him in and thus seems to be trying his best to dissuade her. He’s not particularly friendly towards a female acquaintance with whom we can presume he was once closer, but he won’t tolerate her being mistreated by her boyfriend. He runs a tight ship at the casino but has a pragmatic approach to even dishonest employees. And he’s played by Dick Powell, who made such an enigmatic Philip Marlowe in the 1944 Murder My Sweet. It’s hard not to like him, whatever he may have done to have become the prime target of investigation by the equally likable Koch.

Things soon start to complicate for Johnny. Clearly concerned by Nelle’s flirty behaviour and the fact she gave Guido has the exact same timepiece that she bought for him, he asks Harriet – whom we discover is a hat check girl at the casino – to return the watch to Nelle when she sees her, at the same time advising her to have nothing more to do with the abusive Blayden. That evening, a bloodstained coat fished from the river leads Koch to Harriet’s apartment, where the smell of gas prompts him to break down the door and find Harriet dead in what appears to be suicide. When Harriet’s sister Nancy (Evelyn Keyes) arrives to investigate what happened, the watch Johnny asked Harriet to return to Nelle is still in Harriet’s handbag, together with a terse note of rejection that Nancy immediately assumes was written by Blayden and targeted at her sister. When she asks Koch where she can find Blaydon, the detective points her in Johnny’s direction, and over the course of their first meeting and a later chance encounter, Nancy and Johnny become quite close, unaware that a coroner’s report has revealed that Harriet was poisoned before she was gassed.

By the time he made this first move into the director’s chair, Robert Rossen had already made a name for himself as a screenwriter with such key works as The Roaring Twenties (1939), Edge of Darkness (1943) and Rhapsody in Blue (1945), and as a director he would later really make his mark with films like Body and Soul (1947), All the King’s Men (1949) and, most notably, The Hustler (1961). Critical opinion appears to be a little divided on this directorial debut, which he also adapted from a story by Milton Holmes. Some criticised the film’s unhurried pacing and its favouring of talk over action, and there are certainly more exciting and more complexly plotted noir dramas out there. But Johnny O’Clock has a few aces up its sleeve in the shape of its consistently sharp dialogue, its attention to detail, Burnett Guffey's consistently lovely lighting camerawork and a first-rate cast on excellent form.

Having made his name in musicals like the classic Gold Diggers of 1933 and Footlight Parade, Dick Powell had successfully reinvented his screen persona as a tough guy in the aforementioned Murder, My Sweet and here is able to threaten a man of Lee J. Cobb’s imposing stature and somehow convince you from that he really could beat him if the mood should take him. Cobb is more restrained here than in the roles for which he is most well-known, and there are even moments when Koch’s blend of politeness and easy-going determination casts him almost as a younger version of The Exorcist’s Lieutenant Kinderman. Ellen Drew is a bit of a scene-stealer as Nelle Marchettis, notably in the sequence in which Johnny drops in on Guido and his boys and the half-drunk Nelle openly flirts with him in a way that is comical but also threatens to expose him to Guido’s wrath. As Guido, meanwhile, Thomas Gomez has the air of a man you might treasure as a friend but that you wouldn’t want to get on the wrong side of, a hair-trigger of potentially lethal anger that Nelle’s reckless flirting with Johnny comes increasingly close to firing. Equally impressive is the attention paid by Rossen the screenwriter and Rossen the director to the supporting characters. All of them are cast with care and given interesting things to do or say to ensure that they register, from the loyal hotel clerk (Phil Brown) who politely gives Koch the run-around, to Harriet’s bubbly, cola-sipping replacement at the casino (Robin Raymond). Particularly memorable is Harriet’s nosy elderly neighbour (Mabel Paige), who in the film’s most creative bit of exposition wanders into the apartment whilst Koch is working and, ignoring his requests to leave, sits down and starts reading his case notes out loud.

What really brings the characters and the film itself alive is Rossen’s belter of a screenplay, one so littered with smart lines and creative exchanges that I could fill a sizeable and engaging paragraph with quotes alone. Barely a scene goes by without at least one line that I wanted to scribble down for later recall, sometimes not just because they’re smart but because of what they tell you about the characters. As a dissatisfied Harriet walks away from Johnny after he offers the advice, “Blow your nose and wipe your eyes, in the order named,” he calls her back with a simple, “Come here,” to which she responds with an amusing but revealing, “I’ve been there,” a three-word hint at their past relationship. Johnny’s slick responses to just about everything asked of him by Koch are both part of the front he puts up and an expression of his contempt for the very idea that he should be subject to investigation, and are used to deflect any attempt at intimidation. “It says in my book that any confession obtained by so-called third-degree methods is not admissible in court,” Koch says to him at one point as a veiled threat, to which Johnny casually responds, “It’s nice to know you can read.” Perhaps my favourite exchange involves another economically sketched supporting character when Johnny and Nancy nip into a small restaurant to grab a bite to eat after Nina’s plane is delayed. After being prodded to put down his paper and actually serve them, the establishment’s world-weary waiter (John Berkes) brings them two drinks, which prompts a surprised reaction from Johnny and the following exchange:

| Johnny: |

“Who ordered these?” |

| Waiter: |

“Did you ever eat here?” |

| Johnny: |

“No.” |

| Waiter: |

“You’ll need ‘em.” |

A few seconds later he returns, leans over and lights the candle that’s jammed into a bottle on the table. “Atmosphere,” he says by way of explanation in a voice that is dripping with deadpan disinterest.

Although the noir label is appropriate here and becomes more so as the story progresses, Johnny O’Clock does deviate from tradition by not having the downfall of the central character initiated within the timeframe of the film, having instead laid its foundations some time before the story here begins. It may lack the pace and unexpected twists of the best noirs of the period, and there’s probably a case to be made for Rossen’s directorial style not yet being fully formed, but I still enjoyed the hell out of this awkwardly titled but oddly unsung gem. And while the plot may occasionally feel secondary to the characters and dialogue, when dialogue is this good, its delivery so sharp and the characters so well defined, you’ll not hear a whisper of complaint from this quarter.

Those who know their 40s noir will doubtless let out a wry smile the during opening scene of the 1948 The Dark Past, as the voice of police psychiatrist Dr. Andrew Collins (Lee J. Cobb) sets the scene and he walks into the station in which he works, and the camera adopts his viewpoint in the manner employed throughout The Lady in the Lake just two years earlier. We get to meet Andrew in person as a new batch of criminals is wheeled in and paraded before the police in a line-up, where each is asked to step forward and give his name. The narration continues as Koch delivers his assessment of each man in turn, taking particular interest in the cocksure young hoodlum at the end of the line, whom he believes he could help steer onto the straight and narrow. The lead detective is not so easily convinced, so Koch sits him down and tells him a story about notorious murderer Al Walker (William Holden). It’s only at this point that I realised that this intriguing introduction was merely a scene-setter for a different but related story that then unfolds in a film-long flashback.

A few years earlier, Al has just escaped from prison with the help of his girlfriend Betty (Nina Foch) and associates Mike (Berry Kroeger) and Pete (Robert Osterloh) by taking the warden (Selmer Jackson) as a hostage. As they drive, Betty tells him about an empty lakeside shack she has selected as a hideout in which to await the arrival of a boat that will facilitate their safe departure. Al worries that the shack will be a first target for a police search and is more interested in the nearby house, one in which Andrew spends the weekends with his wife Ruth (Lois Maxwell) and his young son Bobby (Bobby Hyatt). It’s then that Al has them stop and let the warden go, sending him on his way and then coldly shooting him in the back as he departs. “You didn’t have to do that,” the concerned Betty remarks as they drive away, but given that they just revealed where they plan to hide out for the next few hours with the warden in clear earshot, he kind of did.

At the house in question, Andrew – who back then was working as a psychiatrist and an academic – is hosting a dinner party with Ruth for their friends Frank Stevens (Wilton Graff), his wife Laura (Adele Jergens) and their petulant young writer friend Owen Talbot (Stephen Dunne), who may or may not be having an affair with Laura. The guests are in a post-dinner fallout from a terse exchange between Frank and Owen when Al and his troop ooze out of the surrounding woodland and invade the house, where they lock the maid and the cook in the cellar and move the rest into the upstairs nursery with Bobby, except for Andrew, whom Al elects to keep a close watch on downstairs. When Betty persuades Al to take a much needed but fitful nap, she reveals to Andrew that he has been tortured by the same dream for years, and when Al wakes Andrew draws on this in an attempt to slyly psychoanalyse him. Al reacts angrily to his probing but gradually becomes intrigued by Andrew’s claim that if they work together to expose the true meaning his recurring dream, he will never be tormented by it again.

Part psychological thriller, part psychoanalytical drama, The Dark Past is one of several films of its era that reflected a rise in interest in psychiatry and Sigmund Freud’s The Interpretation of Dreams, a trend that peaked in 1945 with Alfred Hitchcock’s Spellbound and its Salvador Dali dream sequences. This notion of unlocking psychological trauma by getting to the true meaning of dream imagery doubtless played like a bold wander into previously uncharted territory in its day, but subsequent developments in psychology and psychiatry have helped to date these films and leave the claims made by movie doctors feeling a little simplistic. And so it is here to a certain degree. Yet despite that, it’s disarmingly easy to buy into it as drama thanks to the unwavering commitment of the lead players, and while you might not swallow Andrew’s literal reading of the symbolism of Al’s dream, the process of getting to the root of a trauma and confronting it is still considered valid in the treatment of psychological issues.

Ultimately, it’s the actors that sell it, and when you have an unwaveringly determined Lee J. Cobb going up against a fiery and defensive William Holden, the tension between them, fuelled as it is by the constant threat posed by Al’s dangerous volatility, effectively renders any improbabilities in the treatment irrelevant. Ultimately, this is not about the accurate interpretation of dreams but the idea proposed in the film’s opening scenes, that adult antisocial or criminal behaviour can sometimes be traced back to a repressed childhood trauma. Perhaps the boldest aspect of this (I’m getting into spoiler territory here, so hop ahead to the next paragraph if you want to play safe), at least for a film made back in 1948 when the Production Code was still very much in play, is the suggestion that even a multiple murderer like Al Walker could be turned around by confronting his inner demons and being forced to face a terrible memory from childhood. Given how ruthless he is shown to be when we first meet him, the fact that I felt sympathy for him by the end is an impressive but risk-taking achievement.

Equally surprising for a film of this vintage is the strong and repeated suggestion that Laura and Owen are having an affair and that everyone around them is aware of the fact, something established early on by Laura’s flirting with Owen and a comment from Frank that seems designed to get right up the testy Owen’s hooter (it does). But there’s more. When the gang first enters the house and Frank gives his new captives the once-over, his first assumption is that Laura and Owen are married. Later, when confronted about her morality by the pompously superior Laura, Betty coolly responds, “You feel sorry for me? That’s a laugh. Pete found you out on the terrace, not with your husband, but with… Romeo. It doesn’t take much to see the kind of life you lead.”

Which brings me to the film’s other principal strength, Nina Foch, a Columbia noir regular whose relatively small role in Johnny O’Clock gives no real indication of just how good an actor Foch was when handed the right role, and she’s absolutely at her My Name is Julia Ross best here. Foch creates in Betty a character every bit as resolute as Al and in some ways stronger, one who stands by him, fights for him, fears for his future wellbeing and doesn’t collapse into an emotional mess when the going gets tough. Indeed, when Andrew’s psychoanalysis of Al appears to be making him more emotionally unstable, Betty’s first response is to tell Ruth to get her husband to leave Al alone, her initial hope for the treatment’s long-term gains now secondary to her concerns for his immediate welfare.

Along with John Huston’s Key Largo of the same year, The Dark Past has the distinction of being one of the first Hollywood home invasion thrillers, and while not as widely known as Huston’s movie, for the performances and building intensity of the drama, it deserves to be. It was the second feature from director and former cinematographer, Rudolph Maté (whose third film, D.O.A., is stone-cold noir classic), who here make emotive use of the tightness of the Academy frame as Andrew pushes Al to dig deeper into his past, and really ramps up the tension in a short sequence when the house is visited by Andrew’s friend and neighbour Fred Linder (Steven Geray). It’s also a testament to all of those involved that they could risk making the climax of a crime movie play out as a verbal battle between a psychiatrist and his patient, and somehow make it as tense and dramatically riveting as any car chase or shootout might have been.

Two bantering detectives are called out to an incident at a nightclub where a young man named Joe Hufford (Glenn Ford) has assaulted another patron in the mistaken belief that he was reaching for a weapon after the two got into an argument about a woman. When he’s brought before District Attorney George Knowland (Broderick Crawford), Joe learns that the boy he hit has died and that he’s likely to be facing up to ten years in jail for manslaughter. Knowland is sympathetic to Joe’s plight and even tries to lay out a good defensive strategy to Joe’s company-appointed lawyer, Vernon Bradley (Roland Winters), a man with no real experience in criminal cases and who chooses to ignore Knowland’s advice, with the result that Joe is sentenced to the full term.

In prison, he shares a cell with Mapes (Will Geer) and tough returnee Malloby (Millard Mitchell), who has a particular grudge against head guard Captain Douglas (Carl Benton Reid) and a strong dislike for two-timing fellow convict Ponti (Frank Faylen), with whom Mapes is planning to escape. By this point, Joe has been working the laundry for six months and it’s really getting to him, and with his father sick he asks to be part of the escape plan, but when news comes in that his father has died, he punches an unsympathetic guard and ends up in solitary confinement. It’s at about this time that Knowland is appointed as the new warden and arrives with his adult daughter Kay (Dorothy Malone) and unhappy elderly housekeeper Martha Laurie (Ilka Grüning) in tow, and when he learns that Joe is incarcerated here, he takes a special interest in his case and wellbeing.

Does any of this sound familiar? It certainly should if you’ve been feasting on Indicator’s recent Blu-ray titles, as it’s also the plot of the 1930 Howard Hawks movie, The Criminal Code, which was released as a standalone disc by the label just a couple of months ago. When I reviewed that release, I and just about everyone one the special features noted that it was based on a play by Martin Flavin and was remade twice by Columbia, and that disc even contained a useful featurette comparing the differences between the three films, which is also included here in a slightly modified form. Convicted is the second of those remakes, and how you respond to it will likely depend in part on what your views on Hawks’ original are. I’m a big fan of that film, and when I wrote about it, I did mention a couple of the reasons why I thought it had the edge on this remake, and I guess now’s the time to get into the rest of them. Don’t get me wrong. Convicted is a solidly made, well-acted and more clearly noir-tinted prison movie, but coming to it so soon after several hugely enjoyable viewings of Hawks’ original I’m inevitably going to be just a little biased, though I would argue there’s more to this than some belief in the notion that first is always best.

Let’s start with Glenn Ford’s performance as Joe Hufford, a character who was named Robert Graham in the original and played by Phillips Holmes. I made the point in my review of the earlier film that Ford was the more accomplished and experienced of the two actors at the times the individual films were made, but also that Holmes feels considerably more vulnerable and less equipped to survive the harsh prison environment than Ford. Good though he is in the role, Ford comes across a man who could hold his own if picked upon, whereas Holmes feels from the start like a helpless kid, one ill-equipped for prison life and who you could easily see the new warden being sympathetic to. This difference in the personality and physical stature of the two characters is acknowledged in the scene in which Joe/Robert is sent to solitary for the second time and picked on by head guard Captain Douglas/Gleason, as while the desperate Robert loses his rag and takes an off-screen beating from Gleason, the defiant Joe angrily throws Douglas out of his cell and doesn’t take a single hit. When it comes to district attorney turned warden George Knowland/Mark Brady, the two films are on a more equal footing, with Broderick Crawford proving every bit as authoritative – if not quite as cockily self-confident – as Walter Huston in the earlier film. Here, however, his personal interest in Joe’s case is given a boost, with the speech about how he should be defended delivered not to his assistant but Joe’s twerp of a defence lawyer. He also recalls Joe’s case here before Joe is brought to his office – in the original, it takes Robert’s response to a comment about his name to jog the warden’s memory. And then there’s Joe’s vengeful cellmate Malloby, who is played here by Millard Mitchell, a talented character actor with a nice line in sardonic tough guys. He’s fine in the role and enjoyable to watch, but never feels anything like as dangerous as Boris Karloff does as Galloway in The Criminal Code. When Mapes remarks that Captain Douglas is afraid of Malloby, we have to take it largely on faith here, but in the earlier film, Galloway’s invitation to Captain Gleason to “Come in and get him” is so loaded with threat that this fact is self-evident.

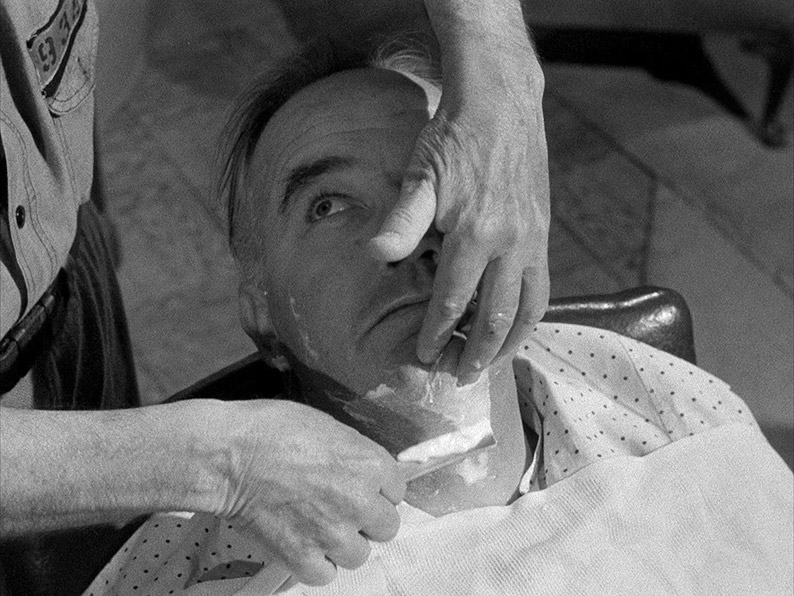

Other changes are more subtle but do sometimes soften the impact of the drama just a little, and while several key scenes from the original play out almost verbatim here in terms of content, Henry Levin’s direction does occasionally reveal why Howard Hawks is still held in such high regard. An example of this can be found in the handling of the scene in which the respective wardens are being shaved by a convict they sent down for cutting a man's throat. It’s a blackly comic sequence that in dialogue terms is almost identical in both films, but it’s how they are filmed the makes the difference. In Convicted, the camera is looking down at Knowland in close-up as the prisoner leans over and starts shaving his throat, which does make Knowland look smaller and more vulnerable than he does while he is standing. But in The Criminal Code this moment is filmed from a low angle and wider and somehow feels more threatening, making the prisoner appear more powerful and intimidating as he leans over and takes a razor to the warden’s exposed throat. The dark humour of the scene is effective in both films, but in the Hawks version this is neatly underscored by a sense of very real danger, one suggested less by what is said and done than the manner in which it is observed.

I guess I’m too fond of The Criminal Code and have watched it too recently to take the sort of unjaundiced view of Convicted that is required of a fair and balanced review, and wondering if a sequence could have been handled a little better is very different to having filmed evidence of how it could be done. Visually, this is also a slightly less appealing film than its predecessor, with the brightly lit, clean and largely featureless prison interior looking more like a film set than a for-real place of long-term incarceration, and elements that were inferred in the original are sometimes over-emphasised here. It’s a good film, no question, but it’s hard to put aside my belief that The Criminal Code was a great one.

| BETWEEN MIDNIGHT AND DAWN (1950) |

|

This is a tricky one. I usually write my reviews before watching any of the accompanying special features, but with my schedule thrown by my medical issues I ended up watching a couple of them just after I’d watched this film and got a bit for surprise. Kim Newman, a man whose views I deeply respect, describes Between Midnight and Dawn as “terrific,” and his praise for Gordon Douglas’s direction is echoed in Adam Scovell’s booklet essay on the film. This left me wondering if I had just been in the wrong mood when I watched it or was distracted by the post-operational pain in my foot. Don’t get me wrong, it has much to recommend it, and one of the things I had a problem with is no fault of the film (I’ll get to that in a minute after a spoiler warning), but I can’t deny that there were a couple of things about Between Midnight and Dawn that kind of bugged me.

It certainly starts in promising fashion, as we join officers Dan Purvis (Edmond O'Brien) and the younger Rocky Barnes (Mark Stevens – who in truth was only a year younger that O’Brien but certainly looks more and his character refers to O'Brien's as "Pappy") as they ride the New York streets at night in a police prowl car and bemoan that night’s run of trivial calls, only to then stumble across an attempted robbery, exchange gunfire with the two perpetrators and arrest them and their girlfriends, who were on watch outside. With the suspects dropped off back at the station, they hit the streets again and are called to a disturbance, one in which a stink bomb has been thrown through the window of an Italian restaurant. The owner, Romano (Tito Vuolo), seems oddly unwilling to identify the culprit, but Dan has a hunch that one of men who work for local big-time hoodlum Ritchie Garris (Donald Buka) is behind the hit. Dan and Rocky pay a visit to Garris’s Starlight nightclub, where they find a car owned by a goon named Joe Quist (Philip Van Zandt) with its engine is still warm and two stink bombs stored beneath the front seat. They arrest Quist and piss off the volatile Garris, but when Romano refuses to identify Quist and Garris’s high-paid lawyer rolls in, station commander Lieutenant Masterson (Anthony Ross) reluctantly admits that they have nothing to hold Quist on and he cockily walks.

By this point, I was getting quite excited for a film that I genuinely never expected to see being made by a Hollywood studio back in 1950, having become convinced by this opening 16 minutes and the timespan title we were going to follow Dan and Rocky over the course of a single night shift for the film’s entire length. How cool would that be? Then, just as I was tipping my hat to the boldness of director Gordon Douglas and screenwriter Eugene Ling, Dan and Rocky’s shift came to an unexpected end. Oh nuts. I put my disappointment aside – one that was completely down to me and not to any promises made by the film or its makers – and waited to see where the film would take us instead. This, it has to be said, is where my problems with it began.

A running gag in these early scenes revolves around Rocky’s fascination with the voice of the female dispatcher and his conviction that she must be really good looking. It’s a seemingly (but unfortunately not) archaic attitude that doesn’t so much prize visual beauty as demand it above all other factors. This woman has a seductive voice that Rocky is attracted to, but if she’s not also pretty then the suggestion is that he’ll no longer be interested. Hmm. What happens next doesn’t exactly help his case. Whilst walking past Masterson’s office, Rocky hears the voice again and concocts some bullcrap excuse to enter the room and get a look at the girl. Her name is Kate Mallory (Gale Storm) and yes, she’s as pretty as he hoped, so pretty that Dan ignores what Masterson is saying and stands uncomfortably close to Kate’s desk and gormlessly ogles her instead. After tolerating this for quite long enough, Kate make her excuses and leaves and Rocky makes up some dumbass question to justify being there in the first place, and by the time he exits into the main office, Dan has charmed the hell out of Kate and the two are getting on famously. The two men then relentlessly badger Kate into going out on a date. With both of them. At the same time. After repeatedly resisting she eventually folds, and for reasons I was unable to fathom, they take her to the Starlight Club and almost inevitably end up in a yelling match with Garris.

My times-have-changed discomfort at the sight of Dan and Rocky browbeating Kate into going out with them (how it is it that in these movies, desirable women are always unattached when the male lead falls for charms that should logically have the power to attract potential partners by the hundreds?) played second fiddle to the growing realisation that the impressively grounded early look at a patrolman’s lot had wandered blindly into romantic comedy territory. This hits a peak after Kate tells the two men that this one date was also the last, and they demonstrate their refusal to take no for an answer by renting the next-door apartment from Kate’s mother (Madge Blake). There’s a “Surprise!” gag moment when Kate opens the door to meet the mysterious new tenants, and later when she storms next door to complain about the singing and banging and ends up sitting down and resolutely accepting that they’re going to stay, I almost expected to hear audience laughter and applause, followed by the closing credits and theme music of the mismatched trio sitcom it seemed to be turning into.

This all changes for the more downbeat and sometimes brutal third act, and the incident that triggers this second directional change was, I would propose, a bold and startling twist for a film of its day. Today, however, its surprise value has been undermined a little by the overuse of similar twists in subsequent years, to the point where one notorious take on it has become one of the biggest clichés in police drama history. Ideally, I’d like to sidestep this completely, but given that this is a considerable strength of a film that has been transformed into a potential weakness through time through no fault of the film or its makers, I really feel the need to discuss it and by doing so will be dropping a mother of a spoiler. So, if you want to go in cold and see if you can guess what’s going to happen as far in advance of its occurrence as I did, then skip ahead two paragraphs or click here to do so automatically. Are we good? Okay then.

Right, for those who know their American cop dramas, see if this prompts any predictions on your part. Young cop and older cop are partnered and hassle a dangerous criminal kingpin. Criminal kingpin gets mad and threatens both men, but they laugh it off. Young cop meets a nice girl. Young cop and nice girl fall in love and decide they’re going to get married. Criminal kingpin is cornered and arrested and vows vengeance. Deliriously happy young cop looks forward to an idyllic future with his bride-to-be but has decided to delay the marriage and the honeymoon until after the criminal kingpin’s trial to avoid interrupting this happiest of times. Criminal kingpin is convicted and once again vows vengeance against both men. At this point the film has almost half-an-hour to run. What do you think could possibly happen next? Yep, it’s a variation on the perennial favourite, “He was just three days from retirement…” Except it’s not. From Midnight to Dawn didn’t adapt a well-worn trope of the police drama, it unknowingly invented one and gave its own twist on what was to become a formulaic plot device by having the younger of the two cops die instead of the one who was so looking forward to a peaceful retirement. The aspect of this inversion of the eventual norm that has carried over into so many later films, of course, is the emphasis on the plans and future happiness of a character that the film then startles the audience by unexpectedly killing off. So overused has this trope become that there can be few today who will not be able to predict that this will happen here long before it does, but back in 1950 at the dawn of the buddy cop subgenre? I’m willing to bet precious few would have seen that coming, and it’s in that context that it should be viewed and judged.

It’s also in this final act that the film really earns its noir credentials, with the angry Dan transformed into a vengeful hoodlum who is not so far removed from the people he is determined to punish. It’s here that the casting of Edmond O’Brien really pays off, with his physicality and ability to suggest a level of barely controlled but potentially murderous violence adding a real sense of danger to his late film encounters. This peaks when he aggressively interrogates Garris’s glamorous girlfriend Terry Romaine (Gale Robbins) and starts slapping her around, and when he doesn’t get the answers he wants there’s a very real fear that he’s going to continue beating it out of her until she expires, something the by-then deeply alarmed Kate puts a timely stop to. As Garris, Donald Buka does tend to overplay the cocky, self-important mobster aspect of his persona, to the point where there are times when this nasally gangster act almost borders on parody. That said, his underlying nastiness comes into its own in the climactic scene, and the sequence in which he attempts to warn off the cops by dangling a small child out of a third storey window (that’s fourth storey for Americans) and threatening to drop her had me genuinely bug-eyed with alarm.

Between Midnight and Dawn is an odd but sometimes seriously impressive crime drama that gets off to an intriguing and nicely observational start, goes off the rails a little when it switches to romantic comedy, then moves into high gear for a compelling and genuinely tense final act. The lead performances – at least those on the side of law and order – are solid, Douglas handles the police business scenes with style, and cinematographer George E. Diskant – who two years later shot Richard Fleischer’s riveting The Narrow Margin – gives the night-time exteriors an ominously moody feel. Eugene Ling’s screenplay may not sparkle in the manner of Robert Rossen’s script for Johnny O’Clock, but it still has the odd memorable exchange. My favourite comes when Dan and Rocky break up a fight between local kids and decide to drive one of them, Petey Conklin (a very good Billy Gray) and his urchin-like brother Thurlow (Tony Taylor) back home. Rocky takes a hard look at Thurlow and says to Petey, “You say he’s your brother?” Petey confirms that he is. “He doesn’t look like you,” Rocky observes to which Petey curtly replies, “I ain’t complainin’.”

The opening sequence of the 1952 The Sniper is without question the most darkly seductive of any of the six films in this set. As the main titles unfold, a young man opens a drawer in his apartment, inside which sits an M1 carbine rifle, which he carefully removes and takes to a nearby open window. As a couple walk down the street below, he switches off the room light and attaches a telescopic sight, then takes careful aim at the head of the woman and, when the moment is right, pulls the trigger. It’s only then that we discover that the gun is not loaded, a practice run perhaps for a crime that has yet to be committed. It’s a foreboding sequence, and while I have no issues at all with George Antheil’s otherwise excellent score, I couldn’t help wondering just how much more unsettling this scene would have been had it been allowed to play out without music or credits.

This potential shooter is Eddie Miller (Arthur Franz), and it quickly becomes evident that he has a few problems. His ire appears to be directed specifically at women, but the roots of his anger are likely more complex than police psychiatrist Dr. James Kent (Richard Kiley) later theorises them to be. In his job as a delivery boy for a dry-cleaning firm, he is regularly berated by his temperamental female boss (Geraldine Carr), yet when he makes a delivery to glamorously attractive pianist Jean Darr (Marie Windsor), he responds shyly but warmly to her friendliness towards him, like a love-struck but unsure-of-himself teenager anxiously waiting for object of his affection to make the first move. When her boyfriend calls to tell her that he’ll be there soon, however, Jean asks Eddie if he’d mind slipping out the back way to avoid making him jealous, and once outside Eddie’s mood considerably darkens. That night he follows Jean to the bar in which she plays and installs himself on a nearby rooftop with his rifle and waits. At the end of the evening, when Jean emerges and pauses to look at and stroke a poster bearing her name and image, she is shot dead, the impact shattering the glass behind her in a move that feels simultaneously realistic and symbolic.

On the surface, this is an act of insane jealousy, an immature but ultimately lethal response to perceived rejection that terminates a relationship that only ever existed in Eddie’s mind. This casts him almost as the paramilitary wing of the modern-day Incels, a loose collective of bitterly insecure young men who define themselves as involuntarily celibate and blame women for their failure to find a partner instead of taking a good look in the mirror to better understand the true reasons. By this point in the film, however, we’ve been given plenty of evidence to suggest that Eddie’s problems run far deeper. There’s that opening dry-run of the shooting, for instance, after which he screws up his face and turns away in the manner of someone not in full control of his emotions and actions, then locking the rifle back in the chest drawer and throwing the key across the room. Walking through town afterwards, he reacts with irritation to two women he overhears gossiping about relationships and in disgust at the sight of couples walking arm-in-arm or kissing. On seeing a mother slap her child around the face, he winces and raises his own hand defensively, an instinctive reaction to a sight that triggers what we can assume is a painful childhood memory. In a drug store, he ignores the flirty looks given to him by the cashier and calls the state prison and asks to speak to a Dr. Gilette. When he learns that the doctor is on a two-week vacation he becomes visibly desperate and begs to be given a contact number that is not forthcoming. On returning to his apartment, he fights the temptation to reopen the chest drawer and instead holds his hand against a hotplate and burns it. He takes the resulting injury to hospital, where a sharp-witted intern (Sidney Miller) suspects he may have psychological issues and asks him if he’s ever been in a mental hospital. “Only when I was in prison,” a surprised Eddie responds, revealing that he was put away for hitting a girl for reasons he still can’t explain and that he was only released from the ‘psycho ward’ because he had served his full sentence. He admits that he doesn’t feel right and seems keen to be kept in, something the intern make initial moves to initiate, only to be mocked by his colleague (Max Palmer) and then distracted by a sudden emergency. Viewed in retrospect, this is the moment where the violence that follows could all have been prevented.

As with the first victim, Eddie’s second target is selected due to a perceived rejection on his part. Immediately after killing Jean he visits a bar, where friendly glances exchanged with a woman named May Nelson (Marlo Dwyer) leads to the two chatting and May writing her name and address on a beermat and slipping it into Eddie’s pocket. They seem to be hitting it off and Eddie is clearly enjoying the attention that May is paying him, but when May realises that Eddie is lying about what he does for a living she irritably cuts him short and returns to her seat, unaware that she has inadvertently become his next target and that she has even given him a location at which she can be found. When she gets home the following evening she’s shot through the window of her apartment, though not before the distraught Eddie has written a scribbled but unsigned note to the police begging them to stop him and warning them that he is going to kill again.

There’s something instantly intriguing about the suggestive simplicity of a title like The Sniper when applied to a film made back in 1952, and of the six films in this set, this is the probably the one that morally takes the most chances. Right from the off we’re as aligned with Eddie and his inner torment as we would be later with the deeply troubled Travis Bickle in Taxi Driver, to the extent that I really felt for him when May cuts their previously friendly conversation short, despite the fact that just minutes earlier I’d watched him take another woman’s life. We’re 24 minutes in before the police enter the story in the shape of the referentially named Lieutenant Frank Kafka (a nicely cast against type Adolphe Menjou) and Sergeant Joe Ferris (Gerald Mohr), who are later joined by aforementioned police psychiatrist Dr. James Kent. Despite their late arrival, Kafka and Kent are sympathetically portrayed, workaday detectives who do their job methodically under pressure from newspaper proprietors and city officials alike, and while Kent’s psychological theorising may seem a little simplistic and dated, it’s he who seems to have the best understanding of the threat they are facing.

Murder, My Sweet (that title keeps coming up) director Edward Dmytryk brings an unsettling matter-of-factness to each scene and handles the narrative development with real aplomb, seeing things exclusively from Eddie’s viewpoint in the early scenes and then widening the focus to include the police investigation of his crimes. This gradual shift is best illustrated by how the first three killings are presented. In the first, we follow Eddie’s every move, in the second only the victim is seen as she arrives home and is killed by a shot through her window, while the third we don’t see at all, learning of it only as Kafka and Kent do and arriving at the crime scene with them almost as part of their team. Intriguingly, at no point do we completely switch sides – despite fearing what Eddie would do next (and at one point having my expectations on this score turned on their head), I found myself wanting him to find the help that he so desperately needs instead than dying in the gun battle that the film at one point appears to be heading for. This willingness to take the unexpected route is carried through to an ending that may not initially seem conclusive but which absolutely right for the film.

Arthur Franz, who was apparently cast almost by chance, really nails it as Eddie, able to switch on a heartbeat from charmingly friendly guy-next-door to tortured serial killer without a hint of melodrama. From the very first scene I believed in Eddie as a character and bought his attempts to control his inner torment as real, and it’s a testament to Franz and Dmytryk that I felt for Eddie even as his mental health really starts to deteriorate. When he loses control at a fairground dunking sideshow and instead of throwing balls at the target hurls them angrily at the cage in which the now terrified female performer is housed, I found myself simultaneously scared for this poor woman and yet also worried that Eddie’s loss of control here would be the thing that finally brought the police to his door. Looking back with the knowledge of the whole sub-genre that was later to follow, it seems doubly extraordinary that the antagonist in what is generally regarded as the first American serial killer film is also one of the most sympathetic.

The supporting cast has also been well chosen, with even minor characters given interesting and pertinent dialogue and playing their parts with an often winning naturalism. It’s also worth placing the film in the content of its time to appreciate the boldness of many scenes, which include a police line-up that seems to exist primarily to educate the viewing audience about the various and sometimes mundane forms that a sex criminal can take whilst simultaneously having a dig at the police for not taking them seriously and instead turning the whole thing into a vaudeville comedy show. It’s one of many remarkable scenes in a genuinely landmark film, one as gripping, thoughtful, well-acted and chance-taking as any of the later works that it unknowingly paved the way for.

The first sign that the 1959 City of Fear is knocking on the door of the 1960s comes early in the shape of the only pre-title sequence in this set, as well as the only one whose picture is not in the Academy ratio. Like a fair few interesting noirs of the period, it starts on the move, as escaped criminals Vince Ryker (Vince Edwards) and William Dabner (I’ve been unable to discover the name of the actor) make their getaway in a stolen ambulance after killing one guard and injuring another. William has taken a bullet to the stomach and wants to turn back, but Vince has stolen a sealed steel flask containing heroin that he plans to cut and sell for what he estimates as million dollars and has no intention of reversing course. When William tries to grab the wheel, Vince pushes him away and he dies. Vince then uses the vehicle’s siren to pull over the car of a cosmetics salesman, whom he kills and puts in the ambulance with his former companion, then takes the salesman’s car, clothes and wallet and picks up a hitchhiking sailor to help him bluff his way through the police roadblocks. He’s heading for Los Angeles to hook up with his girlfriend June (Patricia Blair) and his former associate Eddie Crown (Joseph Mell), but does not realise that the flask does not contain heroin but Cobalt-60, a highly radioactive substance that has the potential to lay waste to the entire city.

City of Fear is director Irving Lerner’s low-budget follow-up to his masterful Murder by Contract, which for my money was the best film in Indicator’s second Columbia Noir box set and were it not for The Sniper I’d very likely be proclaiming this the crowning glory of Columbia Noir #3. And it was so close. As someone who grew up during the tail end of the age of nuclear paranoia, I have a particular fondness – and only as I write this am I realising how arse-about-face this is – for cinematic tales built around the threat of nuclear contamination. It’s that once strongly held belief that atomic annihilation was just around the corner that for me has makes the increasingly rapid clicking of a Geiger counter one of the most frightening sounds you can put in a movie or TV series (and yes, I was crapping myself with fear all the way through Chernobyl). Here, the Geiger counter plays a key role, employed by patrolmen as a tool for detection, a medical instrument for diagnosing radiation sickness and wielded like a weapon by those charged with leading the search for one man somewhere in a city of three million people.

City of Fear is fascinating as much for its feel as for its story and characters. The scale of the story being told does stretch the budget further than the more intimate Murder by Contract and this does occasionally show, notably in the similar-looking shots of police patrol cars (likely the result of only having access to them for a limited time) and the featureless rooms and fenced-off yards dressed to look like police headquarters offices and operation bases. The scale of the operation required to scour a city the size of Los Angeles is also never that convincingly conveyed, a common problem for low-budget films with large scale story ambitions. Does any of this matter? Ultimately, no. City of Fear may bear the Columbia studio banner, but it has all the hallmarks of an independent work, particularly in the almost documentary look and feel of some of its location footage, and it’s worth remembering that this is not a disaster movie but a tightly wound and character-focussed thriller. For almost the entirety of the story, that news that the city is in danger of nuclear contamination is kept tightly under wraps (you can argue about whether you could really trust every Giger counter-carrying patrolman not to urgently advise his family to skip town and inadvertently start a rumour-driven panic), so it feels only right that the general public play little to no part in a story that may never involve them. In its look and tone, City of Fear is closer to Night of the Living Dead than the more recognisably studio produced pictures in this set, which is all the more remarkable when you consider that it was shot by veteran cinematographer Lucien Ballad and was only the second theatrical feature scored by a then 30-year-old Jerry Goldsmith, both of whom give the film’s indie sensibilities a classy sheen.

As Vince, Vince Edwards (yep, same first name) is as cool when required as he was as the initially unflappable hitman Claude in Murder by Contract and on occasion proves to be every bit as cold-hearted. Too fired-up by the prospect of making a mint on the drugs he mistakenly believes he has stolen to listen to the pleas of his injured fellow escapee, he ultimately contributes to his subsequent death is and not remotely bothered by it, while the act of killing a passing motorist and adopting his identity appears to make no dent on his conscience. As he slowly succumbs the effects of the radiation that is leaking from a container that has to be either damaged or curiously unfit for purpose, Edwards believably captures his character’s slow sink into sickness and desperation. This peaks in a sequence in which Vince loses the flask and has to retrace his steps to find it, a narratively redundant scene than nonetheless highlights well how serious his condition has become.

Offering solid support is Joseph Mell as shoe shop manager and backroom drug peddler Eddie Crown, a former crony who is less than happy to see Vince again and a little too keen to get him out of the country, while hovering on the sidelines is Sherwood Price as creepy small-time hoodlum Pete Hallon, a potential thorn in Vince’s side whose keenness to be involved in whatever Vince is up to seals his fate at an early stage. All three are well defined as characters and certainly more memorable than the solidly functional but largely personality-free police representatives, Lieutenant Mark Richards (John Archer) and Detective Sergeant Hank Johnson (Kelly Thordsen), who pop up intermittently to deliver unforced exposition with stern faces and concerned voices, aided by a more emotive Steven Ritch (who, along with Robert Dillon, also authored the screenplay) as resident expert on nuclear matters, Dr. John Wallace.

Lerner’s direction is worthy of particular note here, peppered as it is with techniques that would once have been considered experimental but are now very much part of the filmmaker’s canon. The killing of the motorist and the stealing of his car is a prime example of his way with economic storytelling, fading out as Vince leans into the salesman’s car in wide shot (the salesman himself remain invisible) to allow the main titles to roll and returning to find Vince dressed in the dead man’s clothes and driving his car. Only later are we informed through police conversation of the fate that befell the motorist and fellow escapee William Dabner. Later, when Vince realises that the flask is no longer on the passenger seat of his car, Lerner captures his panic by intercutting mobile shots of the panicking Vince with fidgety handheld footage from his point of view as he frantically searches for the missing object, all of which is cut together with razor-sharp precision by editor Robert Lawrence. At one point, Lerner even cuts between the criminals and the police mid-sentence to connect a detail that Vince missed to its discovery by the police and their irritation at it not leading them anywhere.

City of Fear, like Murder by Contract before it, is the sort of film I so enjoy discovering for the first time that it doesn’t bother me one iota that it’s taken so long to finally see it. Its inclusion in this box set marks it as a Columbia production, but it has the feel of something produced outside of the studio system by enthusiastic and talented newcomers (for the record, Lerner was almost 50 when the film was released). Unlike The Sniper’s Eddie Miller, Vince never becomes a likable character but he remains a consistently interesting one whose slow descent into radiation sickness is still easy to feel for, and the film’s indie sensibility and noir overtones bring a worrying sense of uncertainty over whether that the flask will be recovered before Vince manages to pry it open. It’s a fascinating, forward-looking and gripping work, but one whose most frightening question is left unaddressed – just what possible experiments were the staff at the prison hospital conducting on patients with a substance as deadly as Cobalt-60?

Part 2: Tech Specs, Special Features and Summary >>

|