|

– Part 2: Tech Specs, Special Features and Summary –

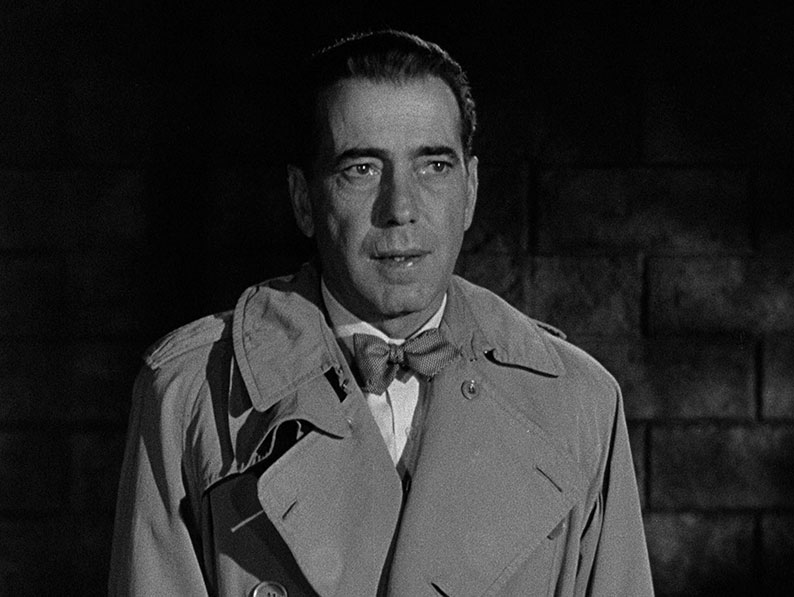

The first five films are presented here in their original aspect ratio of 1.37:1 and were all sourced from Sony High Definition remasters. The Harder They Fall was sourced from a 4K restoration by Sony supervised by Grover Crisp, and is framed 1.85:1. The films are all in impressive shape, and while most are a whisper short of what I’d describe as HD digital sharp, picture detail is almost always well defined (a handful of wide shots are a tad softer), and there’s a nice richness to the image that only 35mm film was able to deliver. As the oldest of the films, Dead Reckoning is just a whisper softer than the norm for the set (it still looks damned good), but leading the pack here on sharpness is Toyko Joe, whose detail is strikingly and consistently crisp. Sirocco is not far behind on this score, and often comes close to matching it, particularly in its close-ups. As you would hope with noir movies, the black levels are dark as an unlit coal mine at night throughout the set, and the contrast is punchy, often with a nicely rendered greyscale between the shadows and the highlights. This does vary a little – you can almost taste the silver halides in the Tokyo Joe transfer, while in The Family Secret the gentler tonal range feels more appropriate to the subject matter, and is attractively rendered. Traces of former dirt and damage are rare, though there are some briefly visible scratches on Dead Reckoning and a few minor dust spots visible on Sirocco. The film grain is clearly evident on the Dead Reckoning transfer, but is considerably finer on the later films.

All six films sport Linear PCM 1.0 mono soundtracks, and while all have the expected restrictions in their dynamic range, the dialogue, music and effects are always clear, and I detected no obvious signs of wear or background hiss. Weakest on this score are Dead Reckoning and (surprisingly) Sirocco, but only by a whisper.

All six films sport optional English subtitles for the deaf and hearing impaired, as do all of the short films detailed below.

DEAD RECKONING

Audio Commentary with Alan K Rode

Film scholar, preservationist, and charter director and treasurer of the Film Noir Foundation Alan K Rode is really in his comfort zone here, and despite a few short pauses and a sprinkling of quips about the on-screen action, he delivers a slew of information on the film and its makers – we even get a considerable amount of detail on the Congressional Medal of Honor, which only figures briefly as a plot point in the film. Other areas covered include the actors (particularly Bogart and Lizabeth Scott), screenwriter Steve Fisher, the Bogart-Lauren Bacall romance and marriage, the dubbing of Scott’s voice for the sequence in which she sings, alterations enforced by the Production Code, and more. He also reads quotes from Scott and co-screenwriter Allen Rivkin, and despite his fondness for Scott, he’s not above criticising a scene in which he diplomatically suggests that she needed a bit more coaching from the director.

Tony Rayns: A Pretty Good Shot (16:37)

The hugely knowledgeable critic and writer Tony Rayns kicks off by suggesting that Dead Reckoning is “a good generic title for a good generic film,” before outlining how it came to be made in its current form and with this cast. He notes that it’s one of a cycle of films featuring servicemen returning from World War II and having to adjust to a changed America, makes a convincing case for the blankness in Lizabeth Scott’s performance being a deliberate choice, and suggests that director John Cromwell was more interested in the actors than the technical aspects of filmmaking, but that he had good collaborators. He also provides details on the lead actors and the issues Cromwell had with the House of Un-American Activities, and provides a useful breakdown of the defining aspects of Film Noir.

Image Gallery

78 screens featuring promotional photos, posed portraits of the lead players, behind-the-scenes images (these are always welcome), trippily coloured lobby cards, and a generous collection of international posters.

Watchtower Over Tomorrow (1945) (15:45)

A short film, directed by Dead Reckoning’s John Cromwell, that documents the formation of the United Nations and the UN Security Council following World War II. Blending staged drama with newsreel footage, it’s driven by one of those trapped-in-time voiceovers that prompt a smile all these years later, especially when delivering lines about “Watching our straight-backed children knocking them out in the ballpark” over shots of kids at play. The arguments are clearly presented without resorting to rah-rah patriotism, and it’s interesting to see Russia presented as an ally considering how quickly the relationship between the two countries soured. Sadly, some of the fine ideals stated here have still not been met all these years later.

KNOCK ON ANY DOOR

Audio Commentary with Pamela Hutchinson

Critic and film historian Pamela Hutchinson takes a lively trip through Knock on Any Door, saluting Bogart’s “beautiful” performance and being familiar enough with the source novel to outline the changes made for the film. She comments regularly on characters and their motivations, and deconstructs various elements of scenes, balancing the ones that may seem obvious with others that are astutely observed. She traces the origins of the film’s most iconic line, makes some interesting observations about the District Attorney’s animosity towards Romano, and confirms a story I read elsewhere about director Nicholas Ray wishing that Luis Buñuel had made Los Olvidados a few years earlier, as had he seen that first then Knock on Any Door would have been a much better film. I think he’s being hard on himself there, but being a diehard fan of Buñuel’s movie, I completely get where he was coming from.

Geoff Andrew: Nobody Knows How Anybody Feels (19:10)

Critic and film programmer Geoff Andrew delivers a thoughtful look at Knock on Any Door, identifying it as a social conscience drama and noting that it is ultimately not about whether Romano is guilty or innocent, but the relationship between individuals and society. He comments on Ray’s use of staircases and claustrophobic imagery, and the vivid, “beautifully paced” opening scene, as well as the small details used to bring new life to familiar elements.

Theatrical Trailer (1:37)

A slickly assembled trailer that obliquely references Oscar Wilde and makes up-front play of the film’s popular source novel.

Image Gallery

59 screen of promotional photos, posed portraits, lobby cards, and a rather splendid collection of international posters of impressively varying design.

Tuesday in November (1945) (17:05)

A short 1945 documentary made as part of the Office of War’s The American Scene series on which Nicholas Ray was assistant director. It looks at how America’s democratic process works, blending staged and documentary footage with the 40s equivalent of animated infographics, which are nicely designed and effectively employed. It’s all very clearly presented and rather wonderfully idealised – Republican and Democrat voters are shown to be smilingly respectful of each other, a very different picture to the one visible in the post-Trump, conspiracy-riddled, increasingly authoritarian America of today.

TOKYO JOE

Audio commentary with Nora Fiore

From the off it seems clear that this commentary by writer and film historian Nora Foire – aka the Nitrate Diva – is going to be a fascinating listen, as she admits that this is not one of Bogart’s best films and suggests that the background to its making is far more interesting than the plot. And she’s as good as her word, providing a wealth of information on a movie I previously knew little about, as well as commenting on performances and scenes that she finds of particular interest. We get detail on the actors (including many of the supporting players), the Tōkyō location footage, the wartime incarceration of the film’s Japanese actors, original story writer Steve Fisher, director Stuart Heisler, cinematographer Charles Laughton Jr, the impact of the blacklist, and loads more. Lively and informative, it also entertains, not least in Fiore’s enthusiastic observations and throwaway comments – “I could just watch Humphrey Bogart walk across rooms all day long,” she notes at one point. No argument here.

Bertrand Tavernier on Tokyo Joe (33:23)

The first of two interviews in this set with The Watchmaker of St. Paul, Round Midnight, L.627 and In the Electric Mist director Bertrand Tavernier, who approaches Tokyo Joe as someone who has always been fascinated by its director, Stuart Heisler. He kicks off by listing some of Heisler’s key films, with particular focus on the documentary short, The Negro Soldier (1944), which is included on this disc. He refers to Heisler’s own comments about the experience of working on Tokyo Joe, which apparently created enough problems for Bogart to apologise to Heisler for bringing him on board and promise him another movie by way of compensation, which came the following year in the shape of Chain Lightning.

A Superstar Returns: Tom Vincent on Sessue Hayakawa (14:16)

Archivist Tom Vincent provides an interesting overview of celebrated Japanese actor Sessue Hayakawa, from his early days in American theatre and movies through to his most famous role as Colonel Saito in Bridge Over the River Kwai (1957) and beyond. Vincent highlights his co-starring role with Anna May Wong and Walter Oland in his first sound feature, Daughter of the Dragon (1931), and makes clear that after having to spend the war years in France under German occupation, his career was effectively revived when Bogart sought him out for the role of Baron Kimura in Tokyo Joe.

An aside. Okay, this is a very personal thing and I doubt it will bother most people one iota, but I’m getting increasingly tetchy about artistically trivial matters in my old age. For reasons unknown, Vincent has been filmed here from two different angles, one with him talking to the camera – i.e. the viewer – the other shot from a three-quarter angle as if he’s talking to someone else entirely. It’s a distracting visual tick that was once briefly popular with producers of DVD extras, being used to disguise jump-cuts caused by excised material (cuts it tends to highlight, I should add) and visually jazz up interviews they didn’t think the viewer would have the patience to sit through otherwise. Wrong! Thankfully, its popularity quickly waned, but it sadly seems to be making a bit of a comeback. At least it’s not hyperactively employed here, and we haven’t yet regressed to the point where one of the angles is in colour and the other in black-and-white. I await with bated breath.

Second Unit Photography (10:08)

Ten minutes of silent footage shot by second unit director Art Black and cameramen Joseph Biroc and Emil Oster Jr in and around Tōkyō in 1948, marking the first occasion since the end of the Second World War that an American company was cleared to film in Japan. The material was scanned in 4K resolution from the original nitrate elements and looks really good here. Shots of servicemen dressed as Humphrey Bogart (and looking nothing like him) riding a bus or walking into buildings sit alongside footage of life on the city streets, including a charming and superbly framed static shot of a street performer entertaining a crowd with a picture show. Fascinating.

Image Gallery

28 screens of promotional photos (including one behind-the-scenes shot), eye-wateringly coloured lobby cards, and posters. The drawing of Bogart on the German one borders on caricature.

The Negro Soldier (1944) (40:27)

Produced by Frank Capra and directed by Stuart Heisler for the US War Department, this time-capsule propaganda piece is as fascinating and impressive as it is retrospectively troubling. Highlighting the contribution made by African Americans to every major conflict in American history, it’s a supremely well-made and engaging watch. Built around a black pastor’s sermon to an exclusively African American congregation, it can be seen as an attempt to break down the racial barriers that then still-active Southern segregation laws had made part of daily life in the Southern states in which most army training camps were based. Particular emphasis is placed on the success of African Americans in war and in civilian life, and shown to a largely unaware white audience of the day – as I gather it was – it must have proved genuinely and (hopefully) positively eye-opening. Counterbalancing this is the film’s likely true purpose as a recruiting tool to be screened in black communities, which in essence reduces it to, “You people are brilliant and deserve more credit, so sign up now and fight for the country that still won’t let you share a washroom with the people who will send you to war.” It all builds to an explosion of Christian patriotic fervour, but the journey there still has its worthy moments, not least when the good Reverend reads a hateful extract from Mein Kampf to remind his congregation of what they’re fighting against, an aspect of the film that is smartly commented on in the feature below.

Jim Pines on The Negro Soldier(40:27)

Recorded at the BFI Southbank before and after a screening of The Negro Soldier, this discussion of the film is led by author and lecturer Jim Pines, who encourages audience participation and gets some interesting responses. One viewer states that while the film is remarkable for its day, it’s still ultimately a shout for American imperialism and that it ignores the horrendous racism the black community faced. Another describes it as a fantastic piece of rhetoric embedded in a Christian context, and bemoans the absence of representation in the media generally of black Jews. Pines himself has an interesting anecdote about his early aspirations to join the American military, and how and why he was dissuaded from doing so by a particularly savvy careers advisor. This is an audio-only piece that runs as a commentary track with the film, and I found it fascinating.

SIROCCO

Audio Commentary with Alexandra Heller-Nicholas and Josh Nelson

Australian film historians Alexandra Heller-Nicholas and Josh Nelson get to grips with what they describe up front as an overlooked film, one that is more than the poor man’s Casablanca it was sometimes dismissed as. One thing they do early on that I heartily applaud is to provide a potted history of the civil unrest and conflict in Syria to help us place the film in the appropriate context. I should note that whenever I review (or simply watch) a film set in a period or place about which know too little, I always research it to gain a clearer understanding of the location and period, and be in a better position to judge the accuracy of the film’s characters, setting and detail. Here, Heller-Nicholas and Nelson do such a sound job that this time around I needn’t have worried. Other areas covered include the source novel and the story’s uneasy path to the screen, the absence of an ideological message, how Bogart’s tough guy persona crumbled in his later films, the orientalising of the Arab world and how this has changed, and much more. There’s information on the actors, novel writer Joseph Kessel, screenwriter A.I. Bezzerides, Santana Pictures, and quite a bit on Zero Mostel, an actor Heller-Nicholas admits to adoring. It’s noted that this is the first film to show Arabs as terrorists, and Heller-Nicholas calls it “the most sexually inert film ever made.” Given how alluring Märta Torén is as Violetta is in a couple of scenes, I’m going to have to disagree with her on that one. Terrific stuff, nonetheless.

The South Bank Show – Bogart: Here’s Looking at You Kid (1997) (51:31)

Ah, this takes me back. The South Bank Show was a London Weekend Television arts show hosted by Melvin Bragg that I rarely missed an episode of. This one focusses on Bogart’s life and career as explored through the eyes of his son Stephen, who had shown little interest in his father’s life until a couple of years previously. A solid and enjoyable introduction to Bogart and his work for newcomers, it includes details of his sometimes tempestuous marriages and is a precious thing in part for the interviews it contains with the likes of Lauren Bacall, John Huston, Stanley Kramer, Angie Dickinson, Gloria Stuart, and Julius Epstein.

Image Gallery

36 screens of production photos, behind-the-scenes shots, lobby cards and international posters, including a couple of curious creations dominated by the words “Bogart’s Socko in Sirocco.”

THE FAMILY SECRET

Audio Commentary with Jason A Ney

This commentary by professor and film scholar Jason A Ney gets off to an intriguing start when Ney reveals how excited he became when contacted by Indicator about doing a commentary for a film in a Humphrey Bogart box set, only to then discover that he’d been assigned the only one in which Bogart doesn’t appear. He then notes that fascinating misfires are often more interesting to dissect than ones that achieve most or all of their stylistic goals. He may just be right. What really impresses here is the insane degree of detail that he goes into on aspects most wouldn’t even think of discussing. Curious about the round-screen television in the Clark household? Well buckle up, because by the time Ney has finished you’ll know enough to choose it as your specialist subject on Mastermind and not pass once. There’s plenty on the main actors, more information on the setting up of Santana Productions than I’ve heard so far, and some interesting comments on things that Ney believes do and don’t work in the film. He does sometimes let scenes play out uninterrupted and comment on them only after they’ve concluded, which technically gives you less commentary bang for your buck, but what is here is so enjoyable and so interesting that you’ll hear no complaining from this quarter.

Image Gallery

31 screens of promotional photos and posters.

The Negro Sailor (1945) (26:49)

Very much in the spirit of The Negro Soldier, this 1945 short, produced by a combination of armed forces film units and directed by The Family Secret’s Henry Levin, is also ultimately a wartime recruitment film, this time to convince young African Americans to join the US Navy. Framed as visualisations of letters sent by a black Navy recruit to his former boss, it follows the young man through his training and his first days of service aboard a destroyer escort with a primarily black crew. Given that these were still prejudicial times and that these films tended to idealise the prospect of military service in an effort to sell it as all rather wonderful, I did suspect that this last detail was a tad fanciful, but a quick bit of research revealed that by 1945 there were indeed naval vessels with smajority black crews. Bravo. Once again, this is slickly assembled and of considerable cultural interest. The picture’s in largely decent shape with a few very visible instances of wear, but the soundtrack is less fortunate, though there was never an instance when I had to switch on the optional English subtitles to understand what was being said.

The Big Moment (1954) (25:23)

An earnest, well-intentioned but sometimes wincingly romanticised and sentimental promo for the United Jewish Appeal. It consists of three stories of lives turned around by a Big Moment: a street kid in Casablanca is goaded into trying to rob a kindly jeweller named Blumenau, who takes pity on the boy and sets him on the right path; a popular immigrant doctor in a small American town gathers some of his patients to tell them he is going to war and introduces them to his newly arrived replacement; a young woman named Deborah is unhappy living on an Israeli settlement with her boyfriend Avrum, so catches a ride to Tel Aviv to start a new life, only to be all turned around on the subject by truck driver Uri. It’s included here because it co-stars John Derek as Avrum, but the cast also includes Donna Reed as Deborah, Thomas Mitchell as Blumenau, and Forrest Tucker as Uri. It’s introduced and narrated by Robert Young and solidly directed by Nathan Juran, who would later helm cult favourites Attack of the 50 Foot Woman, The 7th Voyage of Sinbad and The First Men in the Moon.

THE HARDER THEY FALL

Audio Commentary with Glenn Kenny and Farran Smith Nehme

An initially hesitant (there are a couple of sizeable dead spots early on) but ultimately busy commentary by writers and critics Glenn Kenny and Farran Smith Nehme, neither of whom I initially suspected were as impressed with the film as I was, but who go on to praise many of the things that made it work so well for me. They talk about the author of the source novel, Budd Schulberg, and his unhappiness with aspects of the film (as well as literary critics’ unhappiness with aspects of his book), and opine that there’s not an ounce of fat on the film as a whole, that it shows screenwriter Philip Yordan at his best, that director Mark Robson has no discernible style but a great sense of rhythm, and that Rod Steiger is on fine form in this film and at times genuinely frightening. As a huge Bogart fan, Smith Nehme admits that this movie remains for her a tough watch because of how sick he was whilst making it, but also notes how good he is here and how well made it is. Absolutely.

The Final Bout: Christina Newland on The Harder They Fall(10:24)

Lead film critic with the I newspaper, Christina Newland, delivers an appreciation of a film she describes up front as “a blistering, nasty, pessimistic film noir,” which alone would have had me wanting to see it. She reveals that the film originally had two endings, the softer of which is the one we see here, and usefully outlines some key differences between the film and the source novel. Newland is also filmed alternately head on and at a three-quarter angle, but at least we don’t flit rapidly back-and-forth between them.

Bertrand Tavernier on The Harder They Fall (29:41)

In his second assessment in this set, Tavernier examines what he describes up front as one of director Mark Robson’s best films. Before doing so, however, he dives deep into screenwriter Philip Yordan, who although once regarded as one of the best in the business, was later revealed to have been credited for scripts that were actually written by other, often blacklisted writers. Indeed, Tavernier describes an interview he conducted once with Yordan as, “one of the most beautiful collection of lies I’ve ever recorded.” That said, despite his research on this film, he has been unable to uncover any evidence that its script was written by anyone but Yordan, but that doesn’t stop him concluding that it was just too good to have been written by him. He’s clearly done a great deal of research on this, but while it’s long since been established that Yordan did indeed present scripts written by blacklisted (and even non-blacklisted) writers as his own, I’ve yet to find corroborating evidence of the claim made by blacklisted screenwriter Ben Maddow, for whom Yordan fronted, that Yordan never wrote a word in his life. Anyway, once he’s done with Yordan – and he spends the first third of this interview tearing him apart – Tavernier praises the work of Bogart and Steiger, Burnett Guffey’s cinematography, the location work, and the “undervalued” Jan Sterling. He also notes that when he was young, Bogart was one of only a handful of actors who gave him and his contemporaries hope.

Max Baer Super 8 Films

Two silent Super-8 film records of bouts fought by boxer Max Baer, who has a small role in The Harder They Fall as ill-fated fighter Buddy Brannen. He comes out on top in Max Baer vs Max Schmeling (1933) (2:49), but it’s the second film, Primo Carnera vs Max Baer (1934) (2:51), that is of the most interest, as the character of Toro Moreno was partly based on Carnera, who unsuccessfully sued the filmmakers for claiming he was involved in fixed fights. In the bout recorded here, which took place on 14 June 1934, Carnera was defending the world heavyweight championship, and Baer wipes the floor with him. Read into that what you will.

Image Gallery

35 screens featuring promotional stills, lobby cards, and a solid collection of international posters.

That Justice Be Done (1945) (10:30)

An unflinching look at the atrocities committed by the Nazis in World War II and the courts set up to prosecute and punish those responsible. One of the final films made under the direction of the War Activities Committee, it includes uncensored footage of the victims of the death camps, and it lays the ground for the then-upcoming Nuremburg trails. Directed by George Stevens, the commentary was written by Budd Schulberg, author of the novel from which The Harder They Fall was adapted.

Also included is a weighty 120-page Book that covers the six films in this set in chronological order, with each of the chapters headed up by full credits for the film in question. Before that, there is a thorough and compellingly written piece by writer and film historian Imogen Sara Smith on Bogart and Santana Productions, one that examines each of the films in this set in turn. Next are three 1946 stories from the Tampa Bay Times, the first two of which talk to Columbia’s Ralph Black about location scouting and shooting, while the third chats to second unit director John Sturges, later the director of Bad Day at Black Rock, The Great Escape and a good many others of note. Next is a revealing piece by Jeff Billington on the gay subtext in Willard Motley’s novel Knock on Any Door, which understandably – given the political climate of the day – did not make it into the film adaptation. Following this is a 1949 article from the St Louis Post-Dispatch in which Peter Khiss speaks to Japanese actor Sessue Hayakawa about his role in Tokyo Joe and his wartime experiences in occupied France. The making of Sirocco is reported on by several publications, with particular focus on Bogart’s relationship with Lauren Bacall, to whom he was by then married. Extracts from newspaper stories of the day examine turbulent times for two of the stars of The Family Secret – Lee J Cobb and his run-in with the House of Un-American Activities, and the cancelled contract that saw Jody Lawrence go from rising movie star to waitress at an ice cream parlour, where she was spotted and had her career revived by her former co-star Burt Lancaster. The making of The Harder They Fall is covered in three contemporary articles, the first talking to screenwriter and producer Philip Yordan, the second to wrestler-turned actor Mike Lane, the third to director Mark Robson. I was amused by the opening line of the first of these, by Bob Myers for the Passaic Herald-News, which announces, “Boxing, the dead-end kid of sports, may as well brace itself for another going-over from Hollywood.” Credits and interesting overviews are provided for short films The American Scene, The Negro Soldier, The Negro Sailor and The Big Moment. As ever, the book is handsomely produced and illustrated with promotional imagery.

So universally admired is Humphrey Bogart that to discover someone who genuinely isn’t a fan comes as something of a jolt, as happened to me when I mentioned that I was reviewing six-film Bogart box set to my partner. “I don’t get it,” was her response. “I’m sure he’s good, I just don’t get why.” I should note that this is a discussion we’ve had before about many an artist or artwork, one that has – and indeed logically can have – no concrete, factually-based answer. In that respect, her choice of words is most apt, as when it comes to art of any description, you either get it or you don’t. With Bogart, I get it, I always have got it. I smiled widely when Nora Fiore in her commentary said that “I could just watch Humphrey Bogart walk across rooms all day long,” not because I thought the comment was amusing but because I absolutely knew what she meant. Bogart was an arresting screen presence whose best films are some of my personal favourites, and boy, did he have a run of them. The six films in this set are an intriguing mix of reasonably well-known titles and less widely discussed works, including one of the two films produced by his company in which he didn’t appear, and his own belter of a swansong. Once again, Indicator have knocked it out of the park with this release, with first-rate transfers supported by a terrific collection of special features, including informative commentaries on all six films, a walloping booklet, and a whole lot more. It’s taken me some time to get through it all and write this – hence the length and lateness of this review – but I loved every second of it, and it gets our highest recommendation.

<< Part 1: The Films

|