| |

For the very first time ever

When they had a revolution in Nicaragua

There was no interference from America

Human rights in America

The people fought the leader and up he flew

With no Washington bullets what else could he do? |

| |

Washington Bullets – The Clash |

| |

|

| |

"A guerrilla war is a people’s war, and it is a mass struggle. To attempt to conduct this kind of war without the support of the populace is a prelude to inevitable disaster. The guerrilla force is the people’s fighting vanguard." |

| |

Che Guevara |

Film lore is littered with stories about actors who go that extra mile in their research for playing a specific role. Robert De Niro famously worked as a cabbie in preparation for Taxi Driver and fought as a semi-professional boxer for Raging Bull, while Viggo Mortensen spent time alone in Moscow, St. Petersburg and the Ural Mountain region of Siberia and read books on the Vory v Zakone and Russian prison culture to get under the skin of the character of Nikolai in Eastern Promises. More than once I've heard this approach mocked (always by people who are not actors themselves) with the exact same snarky comment, that these same actors wouldn't go out and shoot someone to get in the right mindset for playing a killer. Which seems to me to be missing the point. Precious few people watching a movie have watched someone cold-bloodedly murder another person, so the portrayal of that act is open to interpretation. But just about all of us have ridden in a taxi, been served by a supermarket cashier, have visited a doctor or spoken to a law enforcement official. And when an actor gets the small details of such a profession right and is able to perform them instinctively, it becomes so much easier to buy them as the character they are playing.

We all tend to get especially critical on this score when the character in question is supposed to be working in a profession that we ourselves are part of. I've worked as a photographer on and off for many years now, and still to this day get irked when an actor playing a member of that profession behaves as if they've just picked up a camera for the first time when by this point in the character's career the equipment should be almost like an extension of their body. This is not an exaggeration – I can almost remember the day when I realised that I knew what ISO setting and approximately what aperture and shutter speed I would be using that day based solely on what I could see in front of me. I also discovered early on that in order to get the shot I wanted, my own safety became a secondary consideration. I'm really scared of heights, but if the angle I needed meant climbing a gantry without seeking official permission then that's just what I would do. I've collected a few minor injuries as a result of this behaviour and landed in trouble with uniformed officials on several occasions. My experiences, however, are nothing compared to those of a friend who years ago worked as a war zone photographer and was once led away by members of the ruling militia for taking the wrong photo to what he and his terrified wife were convinced was going to be his impromptu execution. "I thought I'd had it there, mate," he told me in his calmly pragmatic way.

In the 1983 Under Fire, Nick Nolte plays seasoned war photographer Russell Price, and from the moment we first lay eyes on him I absolutely bought him as the character he is playing. His habit of firing of a whole film-full of shots in a single blast on his motor-driven Nikon aside (for the benefit of those who've grown up with digital cameras, SLRs could shoot a maximum of 36 pictures before you had to change the film), he feels from the off like a guy who has spent a good few years touring combat zones with his cameras slung over his shoulders. He dresses for practicality rather than self-image, his camera equipment is all appropriately worn and battered, and when he holds a camera to take a photo he does so as a photographer would, adopting a steadying posture or leaning against a wall or a vehicle for support. In one almost offhand moment early in the film, he steps out of a taxi and the first thing he does is pull out a light meter and take a reading. You get the feeling that Nolte lived and used this equipment for months before a single frame of footage was shot.* In Under Fire, Nick Nolte is Russell Price. First goal scored.

Actually, it's the second. The first is the opening scene, which begins with a wide shot of a field in Chad in which there is no visible life, but a single electronic note on the soundtrack assures us that something is afoot. Then, unexpectedly, a guerrilla fighter rises into frame from his well camouflaged hiding place, then signals his comrades to do likewise and they emerge the landscape like time-lapsed footage of growing flowers. As they move forward they are intermittently frozen in their movements, and the sound of a camera's shutter and motor-drive – an effect still used on smartphones to inform their users that a photo has been taken – informs us that an unseen photographer is shadowing their every move. As an attack helicopter appears and opens fire and the action hots up, the frequency with which the photos are taken increases and culminates in a perfectly framed (but oddly cropped vertically for this moment – we see the full version later) low-angle shot of a guerrilla fighter riding an elephant with a helicopter in the sky above his head, an image that later makes the cover of Time. Even before we meet Russell Price we have a flavour of how committed and how good a photographer he is. And yet when we catch our first glimpse of him, he's not framed in heroic close-up or in the midst of action, but hanging around by a roadside, smoking a cigarette, checking his cameras and looking for a ride to the next town. There's no sense of "THIS is Russell Price!" about his introduction, more a casual, "Price? Yeah, that's him there." Price is not a journalistic superstar, he's just a guy doing his job, a job he happens to be really good at.

Transport approaches in the shape of a truck carrying rebel soldiers, and Russell scrabbles quickly in his bag for a piece of coloured cloth to tie around his arm that will signify to the fighters that he is on their side. Watch this almost throwaway moment closely and you'll notice that he has more than one colour of cloth in his bag, a subtle indication that had this been a government convoy, a different cloth would have been affixed to his arm. It's a moment that's easy to miss but which speaks volumes about the emotional distance he puts between himself and his subjects, something later verbalised when the temporarily imprisoned Russell says to a priest he is sharing a cell with who asks him which side he's on, "I don't take sides, I take pictures." This detached stance is then perfectly undercut when the priest looks at him wearily and quietly says to him, "Go home."

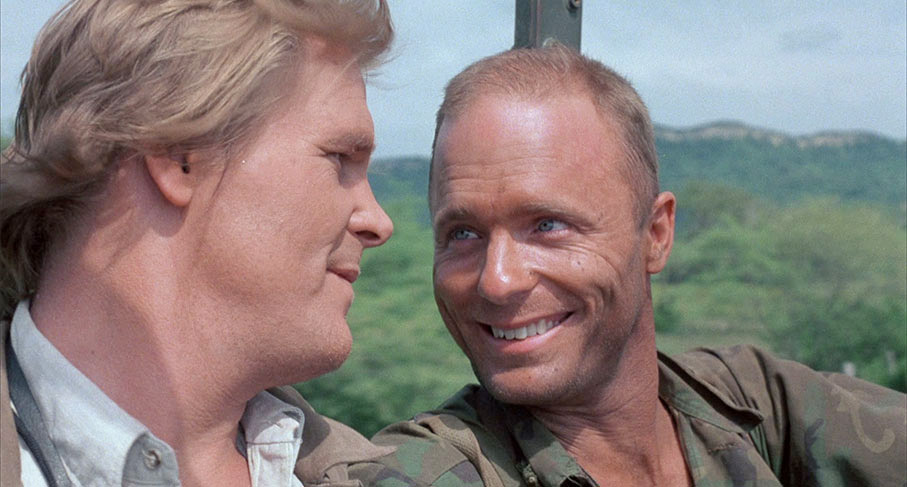

On the back of the truck Russell encounters American mercenary Oates (a key early role for an excellent Ed Harris), a man he's clearly had previous dealings with and who initially comes across almost as a comical rogue when he reveals that he's fighting with the government forces and was unaware that he was riding on a rebel truck. That perception of Oates will dramatically change when he and Russell meet again later in the film (I'll have more to say about this later). It's Oates who puts the idea into Russell's head that the next hotspot for mercenaries and photographers alike is Nicaragua, which is where the bulk of the film will take place. When the truck they are riding on comes under aerial assault, we're given another peek into what makes Russell tick when the soldiers scatter, Oates leaps under the truck for cover, but Russell stays up top to get that perfect picture of the plane as it makes its second run at the convoy (to drop propaganda leaflets, but Price didn't know this in advance). Intriguingly, it's just that sort of reckless determination to get a similar shot that gets a photographer killed in Oliver Stone's blistering and similarly themed Salvador.

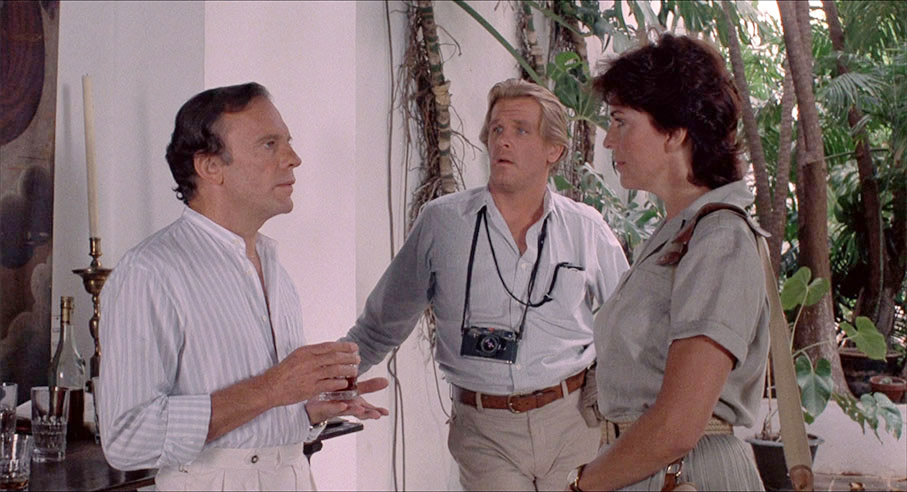

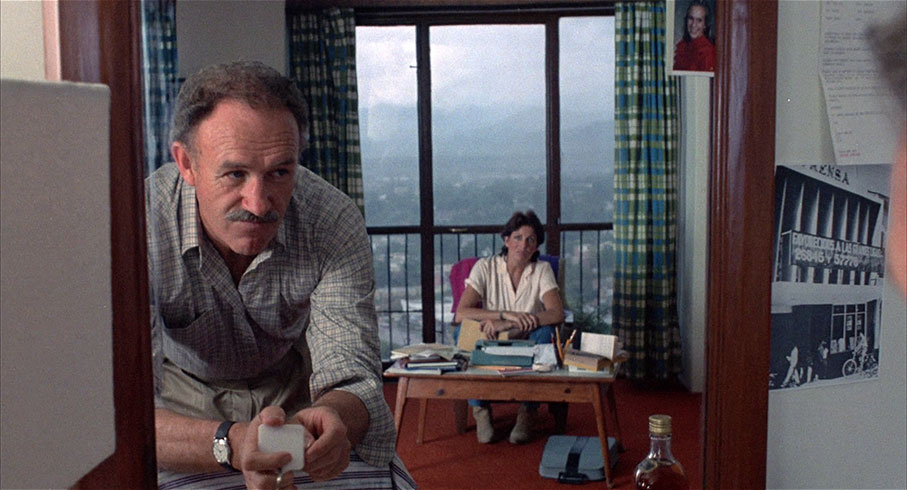

Before we get to Nicaragua, we're introduced to the film's two other principal characters in the form of journalist couple Alex (Gene Hackman) and Claire (Joanna Cassidy), who as we meet them are breaking up before heading to a party that's been thrown in Alex's honour. Alex is chasing a TV job in New York, having become weary of "living out of suitcases," a lifestyle that Claire still enjoys. It quickly becomes evident that Russell has a bit of a thing for Claire, photographing her from a distance at the party and following her into his darkroom where she's gone for quiet cry. Here, Russell's passion for his craft is neatly illustrated when, after he had flirted shamelessly with Claire, she hands him the photo that will soon be on the cover of Time and tells him how good it is, and instead of responding to her flattery he becomes so captivated by the perfection of the image that he doesn't even notice her departure. He really likes Claire, but his first and greatest love is definitely photography.

One neat transition later, Russell is stepping out of a taxi in Managua into a street parade that he immediately starts clambering onto vehicles to photograph, a bad habit that I have to admit I fell prey to after watching this film (it didn't always go as well as it does here). As he shoots, a small group of youths invades the parade waving a placard bearing the image of a revolutionary leader named Rafael. Pandemonium ensues, and when the protesters flee, the soldiers chasing them turn their guns on the placard, a symbol of what they are fighting against. A meeting with Alex in a press-busy hotel garden follows and paints a deceptively upbeat picture of this latest assignment. Alex assures Russell that he's going have a ball with this war, though does drop a not-so subtle hint about Claire by making it clear he still hasn't given up on her.

That evening all three are in high spirits when they go for a drink at a local bar, but it's here they get their first real taste of just what they've walked into when a small group of armed revolutionaries quietly invade the establishment and attempt to kidnap a government figure by holding up a live grenade as they lead him out (a waiter quietly warning Russell and Claire to "stay at your table and you won't get hurt" suggests support for the revolution is not confined to those willing to take up arms). An accident sends the explosive flying and it blows up in front of the bandstand where Alex just seconds earlier had been playing the piano and singing. As customers and staff make their dazed way out of the bar – including three characters we've not yet met but who will later impact on the story – Russell jumps up and starts photographing the devastation, and just for a second the camera adopts his viewpoint to give us a horrifying glimpse of just what a grenade can do to a human face.

Later that day, Russell is violently arrested by a group of soldiers for "taking too many pictures" and is thrown into a cell with the above-mentioned priest. When explaining that this has all been an unfortunate mistake, the commandant makes a point of dropping and smashing one of Russell's cameras as he hands it back to him and refuses to hand over his passport until he signs papers confirming that he wasn't arrested but was paying them a visit. Russell suspects that enigmatic French businessman Marcel Jazy (Jean-Louis Trintignant in his first English language role) has arranged his release, and when he and Claire arrange to interview Jazy they press him into admitting that he is a spy, a role he claims not to be very good at and seemingly plays almost for the fun of it. As with Oates, there is a lot more to Jazy than initially meets the eye.

As they go into the streets on journalistic sorties and at one point hook up with an upbeat group of rebels, Price and Claire get drawn deeper into the conflict and find themselves starting to fall for each other. Russell, however, has set himself a quest. At his first meeting with Alex in the Managua hotel garden, he expressed his determination to photograph the elusive Rafael, despite being assured that he will never find him and that he has never been photographed by anyone. When Somoza interrupts a later interview with Claire to address the social gathering to which she and Price have been invited and informs them that Rafael has been killed, Russell doesn't buy it and continues to enquire about Rafael's possible location, unaware of just where his determination will soon take him.

I should perhaps note at this point that I was initially drawn to the 1983 Under Fire less by its stars or its director and more by the country and time in which it is set. As a politically active young man I was well versed in the turmoil that was Nicaragua in the late 1970s, when a people's uprising eventually overthrew dictator Anastasio Somoza Debayle, whose family had ruled the country since they took power during the Banana Rebellion of 1912. The movement was orchestrated by the Frente Sandinista de Liberación Nacional, the FSLN, more popularly known as the Sandinistas, and in that way thge U.S. has of freaking out at the prospect of any South American country being ruled by the people rather than a U.S.-friendly dictator, Washington had thrown its considerable weight behind the Somoza regime. If you're looking for a detailed account of the revolution, I'd heartily recommend George Black's painstakingly researched book, Triumph of the People, at least I would had it not been out of print for some years now.

Complaints have been made that this uprising becomes mere background action against which the personal dramas of the western characters play out. While I accept this criticism, it's one that has been – and indeed has to be – made against all entries into this particular subgenre, one that tends to feature white western correspondents who travel to (or are stationed in) another country during a period of war or civil unrest and are dramatically changed by the experience. The subgenre was particularly popular in the 1980s and included widely respected films such as Oliver Stone's Salvador, Roland Joffe's The Killing Fields, Volker Schlöndorff's Circle of Deceit, Nathaniel Gutman's Deadline and Peter Weir's The Year of Living Dangerously. The argument made against them is that the personal stories they tell tend to trivialise and over-simplify the conflicts against which they are set, while the filmmakers (and particularly those putting up the money) would doubtless make the case that they are making these films for a primarily western audience that will only become involved in a story if they are able to directly identify with the lead characters. Whether this is actually the case is up for debate, but it's certainly a common perception, particularly in Hollywood – when asked why the two lead characters in Mississippi Burning, a story of sometimes violent racial prejudice in America's Deep South, were white when the struggle the film depicts was a primarily black one, director Alan Parker memorably replied that the decision was all about bums on seats.

I do not, however, accept the notion that this somehow invalidates these films as art, entertainment or even political cinema. It's true that they almost never present the conflicts in which they are set from the viewpoint of those directly involved in and affected by them or provide a thoughtful look at the politics and history of the situations in which they are set. I would argue, though, that this is the province of the documentary feature or series, and that it would be nigh-on impossible to adequately cover these elements and tell a dramatic story in just two hours of screen time. Consider for a second that the aforementioned Triumph of the People consists a densely (and I mean densely)packed 368 pages of fact-crammed text, while if you're looking for a comprehensive look at the Vietnam War, then you'll need to put aside a full 16-and-a-half hours to take in the extraordinary documentary series of the same name by Ken Burns and Lynn Novick. I'm thus not going to claim that these foreign correspondent films come even close to painting a full picture of the conflicts in which they take place, but would suggest that they do open a small window to situations that a sizeable portion of the potential audience might not have previously been aware of, a window that we can only hope a few of those who are new to the information might be ready to jump through. As I stated above, I was already familiar with the details of the Nicaraguan struggle, but freely admit that I knew too little about the atrocities committed in Cambodia when I first saw The Killing Fields, and was completely ignorant of Indonesia's 30 September Movement when I first sat down for The Year of Living Dangerously, yet shortly after watching both films I was down at the local library reading up on both. These films are never going to be a complete package on this score but for a few, at least, they are a useful starting point.

In this respect, the background detail of Under Fire is a fascinating melding of fact and fiction. On one of the commentary tracks on this disc, Matthew Naythons – who worked as a photojournalist during the Nicaraguan revolution – testifies to the authenticity of specific sequences and much of the detail, while the age and gender mix of the FLSN rebels appears to be on the nose, aided by some fine work in the casting of supporting roles. The figure of Rafael is an invention, however, a hybrid of Che Guevara and Augusto Sandino whose image can be painted on placards and walls and who later provides the film with one of its most important and electrifying scenes, one that marks a turning point for the film, the struggle, and for Russell and Claire's previously guarded neutrality. The film also draws on a true-life story that did indeed help to change the course of the conflict, but it's one that I can't discuss without delivering a massive spoiler that you absolutely should not know about before you see the film. Yet I can't avoid it if I'm going to talk about some of the film's most compelling elements and what for me may be the most telling exchange in a script that is littered with smart dialogue, the first feature script by Bull Durham and White Men Can't Jump writer-director Ron Shelton. Worry not, the paragraphs (and there are several) in question will be headed with a spoiler warning and a bypass link.

Where Under Fire really delivers as drama is that, in common with Salvador, it weaves the dramatic elements into the fabric of a tightly constructed political thriller. That Russell will eventually abandon the neutral stance that has served him so well for years is inevitable and provides the film with its main dramatic arc, but it works so well here because events unfold around him in a manner that make it easy to see how he might come to sympathise with the rebels and their cause. Shrewdly, Shelton and Spottiswoode also avoid the trap of painting Somoza as a cartoon dictator and instead present him as he liked to present himself to visiting journalists, as a smiling and ostensibly benevolent leader who uses proud talk of his family's history to deflect from Claire's questions about poverty and the death squads. Only in a moment of explosive anger at being interrupted do we glimpse the tyrant lurking beneath, and there's an appropriately grotesque sense of finality to his regime when he looks on as a construction crew digs up the coffins of his parents so that they might be transported out of the country with him. It's a finely judged performance by René Enríquez, who at this point was known primarily for his role as Lieutenant Ray Calletano in Hill Street Blues and who was – and I only discovered this recently – a nephew of former president of President of Nicaragua, General Emiliano Chamorro. The notion of giving Somoza an American PR man in the shape of Hub Kittle, on the other hand, risks coming across as contrived and even a little cheesy (see the deleted scene on Eureka's Blu-ray of Salvador to see how easily this concept can fall on its face). A nicely judged performance by Richard Masur sells Kittle as real, however, and his few appearances are quietly memorable, ineffectually challenging Alex's weary but spot-on telephone complaint to his superiors that "we're backing fascist governments again – I know that's nothing new" and later the recipient of one of the most perfectly timed and delivered requests to fuck off that I've yet seen in a movie.

The film is judicious in its presentation of violence, which often comes out of nowhere and then quickly recedes, leaving us and the characters with the shock of its aftermath. Similarly rationed is Jerry Goldsmith's consistently extraordinary music score, which brings a real sense of vibrancy to an FLSN camp morning montage, conspires with a gentle tracking shot to convince us that a scene has reached its conclusion so that we will be more shocked by the turn of events that follows, and warns us of the horrors to come with a single wavering electronic note that accompanies Russell and Alex as they search war-torn streets for a forgotten location. Just as effective is its absence from sequences that others would score, with whole scenes of nail-biting conflict playing out with no musical accompaniment. This adds to the already potent air of documentary realism created by master cinematographer John Alcott, who apparently shot most of the film using available light and practicals (light sources that feature in the scene such as lamps and candles), a signature of a cinematographer who is most famous for the sumptuous candlelit interiors of Stanley Kubrick's Barry Lyndon. And when the film needs to be tense, it's absolutely nail-biting, notably in a late-film sequence in which Russell has to flee for his life and the stakes for his survival are far higher than the survival of a single American photojournalist.

Ah yes, that sequence. This is where newcomers to the film should skip ahead, as in order to discuss this crucial turning point for the film, the real-life incident that inspired it and how it is shaped in part by the Russell-Alex-Claire love triangle that some claim dilutes the film's impact, I'm going to have to deliver a massive spoiler. It's a turn of events that nobody seeing the film for the first time should have foreknowledge of, and thus if you've not seen the film and have managed to read this far, then I urge you with all my heart to skip to the final paragraph of this review. You can do so easily by clicking this link.

SPOILER ZONE

If you're still reading I presume you know the film and have already worked out what sequence I'm referring to. It's foreshadowed by an earlier scene in which Russell and Claire go out in search of a story with three members of a TV news crew in their battered Volkswagen van and suddenly come across a military roadblock. Here their fate is nearly sealed by one of their own number when the driver panics and throws the vehicle into reverse instead of stopping as requested, a foolish move given that everything about the soldiers' body language suggests all they'd have done is check their papers and send them on their way. Soon the vehicle is belting down abandoned and conflict-damaged streets and coming up against further roadblocks, whose soldiers by then are losing patience with the driver's refusal to stop as ordered and open fire on the van. It ends when the vehicle comes face-to face with a tank, which then fires a shell not at the quickly abandoned Volkswagen but at a dropped TV camera. It's a symbolic gesture that risks denting the reality of the situation but instead carries echoes of the earlier sequence in which Russell's camera was smashed by a police commandant in a move designed to make it clear what the military thinks of the press. Thus, when Russell and Alex return to these same streets at a later date and lose their way, we already have a sense of the danger they potentially face. And when they stop to ask directions and an old woman suggests Alex talk to a group of bored soldiers a little further down the road, the casual nature of the encounter is still heavily tinged with a sense of unease.

When an unknowing Alex is told to hand over his papers and raise his hands and is then unceremoniously shot dead, the electric shock it delivers is very much down to how the sequence is directed and played. Crucially, Alex's approach to the soldiers and his encounter with them is framed entirely in wide shot from Russell's viewpoint as he sits in their car a little further up the road, taking the odd picture because, well, that's what Russell does wherever he goes. When the shooting occurs, there are no dramatic close-ups of weapons or Alex's face, just the same POV wide as the gunshot rings out and Alex falls to the floor. The shock effect comes from a combination of the absence of cinematic foreshadowing, the casual behaviour of the soldiers and their victim, the fact that Alex is played by a name actor and the horrifying sense that this is exactly what seeing someone shot in real life would look like. And while there is a dramatic music cue, it doesn't kick in until after Hackman has fallen – in keeping with Goldsmith's desire to capture the emotion of the character in a scene, the music doesn't over-dramatise the shooting but instead functions as an expression of Russell's shock and outrage. This is also one time when Russell's (or should that be Nolte's?) habit of running the camera's motordrive makes complete sense, as the impact of what is unfolding before his eyes would have prompted him to instinctively tense up and keep his finger pressed on the shutter release.

Now I should point out that having said all this, on my first viewing of the film back on its release (when I was one of only four bloody people in the sizeable cinema in which it was playing locally) I remember being convinced that Alex was going to die even before he reached the soldiers. This was not down to the film – others who recalled their first viewing have confirmed this for me – but to a horrifying piece of news footage I saw four years earlier that had seared itself into my then young brain. For those who do not know, Alex was based partly on American TV journalist Bill Stewart, who on 20 June 1979, after being forced to hand over his papers and lie face down on the floor at a military checkpoint in Managua, was shot in the head by a one of the soldiers. The incident was captured on film by Stewart's cameraman Jack Clark from almost the exact same distance that Alex's death is photographed. Clark was able to smuggle the footage out of the country, and in common with how events play out in the film, Somoza initially blamed Stewart's death on the Sandinistas, but once the footage was screened all American support for Somoza was cut off and his government quickly fell.

On the commentary track of Salvador, director Oliver Stone cites Under Fire as an excellent film in a similar vein to his own, but elsewhere has criticised the love triangle story at its centre as an unnecessary distraction, a view echoed by a number of the film's detractors. Again, I'm going to have to disagree. The relationship that unfolds between Russell and Claire is typical of writer Ron Shelton in that it is maturely and believably handled and devoid of sentimentality. It adds a further level of urgency to their actions and their forced separation, while their complicity regarding the truth of Russell's photo of Rafael (if you're reading this you should know exactly what I mean) – a complicity that would probably not have happened were they not so close to each other – indirectly contributes to Alex's death. Alex wouldn't even have been in Managua had he not believed that Russell had the necessary connections to secure a TV interview with Rafael, and when he finally learns the truth, the fact that he doesn't break what would be the biggest story of his career is down solely to his past relationship with Russell and Claire. He instead settles for an interview with the mysterious and enigmatic Jazy, and the search for his house after being redirected by soldiers is what lands Alex and Russell at the lethal checkpoint in the first place. His death also gives rise to what may be the film's most telling exchange, when a tearful Claire stops off at an FSLN filed hospital and sees Russell's photos of Alex's execution on TV, and this quietly delivered but memorable conversation unfolds between her and a weary female doctor (I'm noting that she's female because I believe the equality of gender matters here):

| Doctor: |

"Did you know the man who was killed?" |

| |

Claire Nods |

| Doctor: |

"Fifty thousand Nicaraguans have died and now a Yankee. Perhaps now America will be outraged at what has happened here." |

| Claire: |

"Perhaps they will." |

| Doctor: |

"Maybe we should have killed an American journalist fifty years ago." |

That's a bold but powerful bit of writing, albeit one that sent a few shivers up my spine at a time when the current American president is branding the press of his own country "the enemy of the people" in an attempt to deflect from the unpleasant truths they are uncovering about him. I'll bet he would have loved Somoza if he was still in power and killing his own people and told those attending his rallies what a "fine person" he was.

While the photos Russell takes of Alex's murder help the revolution to succeed – just as the footage of Stewart's death did in the real world version of events – the film also presents us with an altogether more troubling narrative in which his images are put to destructive use. Initially, the harm they cause is close to home, as Alex drops in on Claire and discovers pictures of her taken by Russell that confirm what he only previously suspected about their evolving relationship, which prompts him to invent a story about why he has chosen to head back to home turf. Later, however, Russell and Alex are alerted by gunshots to the presence of a backyard death squad being run by Oates, who is using the photos that Russell took of the residents of Rafael's camp to identify them as targets for execution. A deeply disturbing notion in its own right, it today acts as a chilling reminder of the surveillance society in which we all now live and how the vast quantities of information now held on us, complete with images and information we voluntarily post, that could in the wrong hands be put to potentially terrifying use. And there are a lot of wrong hands vying for power at the moment.

It's in the character of Oates that the film takes one of its biggest risks but where it also refuses to sugarcoat the truth. Mercenaries have been a feature of just about any conflict you care to name for decades, and though the opportunistic Oates is a supporting character who only makes four appearances in the film, the first three of these have a significant impact on Russell's fate and his emotional detachment from the subjects of his photography. In the first, the conversation he has with Russell is instrumental in making him aware that Nicaragua could be the perfect location for his next job and in that respect effectively kickstarts the main story. In the second, after hiding amongst bodies on a church roof following a grenade attack by a small group of rebels that has invited Russell along to take photographs, Oates briefly converses with Russell ("What do you think of the war?" he asks him, to which he replies in all sincerity, "It's beautiful"), then as Russell and Claire are walking away and cheerfully chatting with the four rebels, Oates murders their star grenade-thrower from the safety of the church roof, an action that so angers Russell he drops his camera and picks up a rifle instead. By the time Alex and Russell discover Oates running a Somoza death squad, the likeable (if troublingly racist) soldier-of-fortune from their first encounter has evolved into a monster, one with no regard at all for the sanctity of life and who sees the disposal of people as nothing more than a paycheque. Most films would demand that such a character be killed to reward an audience that still expects bad guys to suffer for their crimes, but here he survives the revolution and turns up at the end in a flowery shirt acting as if he was with the rebels all along. "It's a free country," he says to Price on being asked what he's doing here, adding, almost humbly, "I mean, it's free now..." We just know that a few weeks later he'll be fighting for the American-backed Contras against the very people with whom he cynically stands in celebration.

END OF SPOILERS

That I've had to struggle to stop writing about this film tells you something about how much there is in it that I deem worthy of discussion, and know that even with everything I've written I'm cutting myself short. There's so much more I would love to talk about and expand on here had I not already missed the release date of this Blu-ray and were there not a whole stack of other discs screaming out for my attention. For me, every element in the film works divinely. Ron Shelton's script is masterfully structured and blends the personal with the social and political with a deftness that belies the fact that this was his first feature script. A superb cast really gets under the skin of the characters, with Nolte, Cassidy, Hackman and Harris at the top of their considerable game and care taken with the casting of even the smallest role. John Alcott's beautifully naturalistic cinematography and some nifty work by a production design team led by Augustin Ytuarte and Toby Rafelson help create a vivid sense of a war-torn Managua in the Mexico locations, and I'll tip my hat to costume designer Cynthia Bales for creating clothing that doesn't just feel authentic but authentically worn and lived in by people who don't get to change their clothes every day after a morning shower. John Bloom and Mark Conte's editing is masterful without ever drawing attention to itself (it must be just a little intimidating to be editing for a director who, as a former editor himself, worked on Straw Dogs, Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid and The Getaway for Sam Peckinpah, editing masterclasses all), and Jerry Goldsmith's score is one of the finest in a career that is just littered with astonishing music. Crucially, none of these elements succeed in isolation, and it's to the director Roger Spottiswoode's considerable credit that they all pull together in such sublime harmony. His direction of individual scenes is masterful, and he takes his cue from Shelton's script in its refusal to structure or pace the film according to Hollywood convention. I can't be neutral here and don't see why the hell I should be. Since the first time I saw it, Under Fire has held its position steadfastly as one of my very favourite films, and for me is one of the finest achievements of 1980s American cinema and one of the great political thrillers of late 20th Century cinema.

A rather lovely 1080p transfer framed in the film's original aspect ratio of 1.85:1 that occupies seemingly all the space on the disc not taken up by the special features, and that's a lot. In an era of almost obsessive digital grading, how nice it is to watch a film with such naturalistic colour, which is handsomely reproduced here and boasts rich rendition of brighter primes. The contrast is very well balanced with solid black levels but clearly defined shadow detail, and the image is consistently sharp in that organic way that digital still hasn't managed to quite reproduce. A fine film grain is evident and there is no sign of damage and very few dust spots.

The Linear PCM 2.0 stereo soundtrack is very clear and with a strong dynamic range, no grating crispness to the trebles and a solid punch to the bass of effects like explosions and engine sounds. The music sounds terrific and the stereo separation is often very distinct.

Optional English subtitles for the deaf and hearing impaired are available.

Director Audio Commentary

The first of two commentaries that are incorrectly – or perhaps that should be imprecisely – titled on the disc's main menu, both of which are hosted by documentary filmmaker, record producer and enthusiastic fan of Under Fire, Nick Redman. As far as I am aware, Redman passed away earlier this year and I gather these commentaries were originally recorded for an American release of the film by Twilight Time, for whom Redman worked. Here he is indeed joined by director Roger Spottiswoode, but also Paul Sedor, who worked as editor John Bloom's assistant on the film, and by Matthew Naythons, who was the film's technical advisor and was the Time photographer in Nicaragua during the Sandinista uprising. Although only rarely scene-specific, this really is a terrific commentary. Spottiswoode provides a wealth of information on the making of the film, including how they tricked Nick Nolte into reading the script and convinced Jean-Louis Trintignant to appear in his first English-language film, and how the preparation for the opening sequence set in Chad (but shot in Los Angeles) nearly collapsed. He discusses his approach to shooting action and the thinking behind a couple of key scenes and also has an entertaining story about editing a scene in Straw Dogs that no-one else would touch and his terror at having to screen the result for Sam Peckinpah. There's much more. Naythons' contributions I found particularly illuminating – it's here I learned that the cameras Nolte uses in the film were all his, and he has some hair-raising stories about his time in Nicaragua, including some relating directly to Bill Stewart, whose name will probably mean nothing to those who skipped the spoiler section, which is why I'm not going to expand on that comment. I became so engrossed in this I didn't want it to end, and a story about the film's Venice Film festival screening sees Paul Sedor keep talking almost until the last frame of the final credits.

Bruce Botnick Audio Commentary

Once again the title doesn't tell the whole story, as while Nick Redman is indeed joined by Bruce Botnick, who co-produced the film's soundtrack album with Jerry Goldsmith, they're joined by Jeff Bond, who used to write about film music for The Hollywood Reporter and has written a lot specifically about Goldsmith, Kenny Hall, who was supervising music editor on the movie and worked on 87 films with the composer, and Julie Kirgo, a writer and film historian who also does a lot of work for the Twilight Time label. If you somehow haven't already guessed from this intro, the focus of this commentary is composer Jerry Goldsmith and his score for the film, and just a couple of minutes in I was convinced that I was the wrong person to be reviewing this particular extra, as my esteemed co-writer Camus knew and worked with Mr. Goldsmith and stayed in contact with him until his death in 2004. Yet so much of what is discussed here is so interesting that even if the idea of talking about a giant of film composition doesn't particularly appeal (what's wrong with you?), I'd urge you give this a listen regardless as I found it every bit as educational and entertaining as the previous commentary. What makes this one special is that it provides us with an insider's view not just of the writing and recording of this score, but of Goldsmith's approach and technique and the production of the soundtrack album (still a treasured part of my record collection), and is peppered with engaging and illuminating stories. Not all of them are positive, notably Hall's recollection of a first mix of Under Fire that effectively decimated Goldsmith's score, an experience that reduced him to tears and that he still regards as one of the worst times of his life. Goldsmith himself subsequently intervened and this clearly did the trick, as everyone present has nothing but good things to say about a film they all regard as remarkable and whose qualities are most perceptively highlighted here by all. There are many enjoyable stories, but my favourite revolves around two orchestra members who solved the problem of not having access to pan pipes when recording the score in London by making some with PVC plumbing pipes and gaffer tape, and that's what you hear on the soundtrack. I also rather liked Jeff Bond's claim that modern directors are "both more afraid of music and more afraid of not having music." There's so much good stuff here. A terrific listen.

Joanna Cassidy Remembers ‘Under Fire' (3:06)

I was all fired up for this until I saw the running time, which does not allow for any in-depth recollections and settles on a small handful of expected topics including how Cassidy landed the role, working with Nick Nolte and shooting in Mexico. She regards the film as one of the most beautiful she's ever seen and describes the score as "phenomenal." She also still has the most wonderful laugh in the movie business.

Theatrical Trailer (2:57)

"They fell in love... in a country under fire." From that period where trailers featured terribly sober narration. Lots of shots of Nolte taking pictures and a few too many spoilers to be safely watched just before the film itself. Not the most persuasive sell, given the strength of the material they had to work with.

Booklet

In here we have a fine essay titled A Neat Little War: Under Fire and the Nicaraguan Revolution by Scott Harrison, which provides some useful background on the Sandinista uprising and fills in a few of the small gaps left by others on the making of the film, whose box-office failure and critical reception Harrison also covers. The main credits for the film and a selection of stills have been included.

Too long? Oh come on, you should know what we're like by now, and believe me if I didn't have a review for the Indicator Blu-ray of Scum tugging at my heels, I've have delayed this another week and written a whole lot more. No fence-sitting here – I absolutely fell in love with Under Fire when I first saw it and it looks as marvellous as ever today. Eureka has delivered a lovely transfer, and while it may seem there are not many extra features, those two commentaries alone are worth their weight in diamonds. Highly recommended. But you knew that, didn't you?

|