"The

world belongs to the young. Make way for them, they

can have it." |

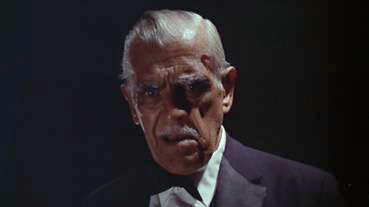

Byron

Orlock |

It's been famously claimed that guns don't kill people, people do.

But when those people use guns to do it, this particular tool – whose primary purpose is to main or kill, after all – has to take a sizeable part of the blame. The issue of

easy availability of firearms in the US has been a contentious

one for as long as I can remember, and any politician who

makes gun control a campaign promise is usually deemed to

be committing electoral suicide. The debate has been irregularly

highlighted by a tragic series of shootings at American

schools, and was pushed into the mainstream by Michael Moore

and the international success of Bowling for Columbine.

But guns remain freely available, and people continue to

die at the hands of those exercising their constitutional

right to bear arms.

Since

its early days, cinema has glamorised and even trivialised

the gun. In movies it's a prop, a tool employed to both complicate and

resolve a narrative thread. If you get shot in the movies, you fall

down, maybe bleed a little, and drop out of the story. Wielded by the good

guys, guns are tools for justice, and when they are used

to kill the innocent it's because they fall into the hands

of the wicked, the naïve, or the mentally unhinged – guns rarely make

it into the news unless they are put to destructive use

by one of these three. This allows those who believe in

the right to bear arms to remain comfortable with the free

availability of deadly weaponry – killing sprees are executed

by insecure loners with a grudge, people not at all like

them or their friends or family. Guns don't kill people,

the socially excluded do.

Oh

really? Time for a brief trip back through not-so-ancient

history.

On

27 November 1978, former policeman and San Francisco city

supervisor Dan White, a well-liked man from what the well-to-do

like to describe as a good background, entered City Hall and shot

Mayor George Moscone, then walked into the office of supervisor

Harvey Milk, the city's first openly gay official, and emptied

five bullets into him. Both victims died of their wounds. White

was sentenced to a mere seven years and eight months and

served less than five. The gun he used was not an issue,

White's lawyer contesting that a diet of junk food – the

notorious 'Twinkie defence' – was responsible for his 'out-of-character'

behaviour.

On

20 August 1989, wealthy businessman Jose Menendez and his

wife Kitty were murdered with a shotgun in the supposed safety of their $4 million

mansion. The crime was reported by their distraught sons

Joseph and Eric. Over the next four months, the two sons

spent over a million dollars of their father's money, and

in March of the following year were arrested and charged

with the killings. At the trial they admitted their crimes,

but claimed they was prompted by years of sexual abuse. The

jury was deadlocked and a mistrial was declared. The second

jury did not believe the brothers' claims and they are found

guilty on two counts of first degree murder.

On

31 July 1966, former Eagle Scout and ex-U.S. Marine Charles

Whitman stabbed his wife and mother to death. The following

day, armed with a sniper rifle, he climbed the Bell Tower

at the University of Texas, and in the space of ninety-six minutes

killed sixteen people and wounded a further thirty before being killed

himself when armed officers stormed the tower.

I

could go on.

And

yet still the movies tell us that it's only those on the

fringes of society that guns turn into killers. Even the

recent Dear Wendy,

an intelligent and well made film, chose to illustrate the danger of

firearm obsession by placing guns in the hands of misfits

and losers. You could be forgiven for wondering when a film-maker

would be brave enough to show that even the most upright,

clean living American boy could, with free access to guns,

turn without warning into a mass murderer. As it happens, you don't have

to wait at all, but take a trip back to 1968 and Peter Bogdanovich's

astonishing first feature, Targets.

The

story of how the film came to be has become part of film

lore. Having directed sequences for Roger Corman's Wild

Angels, Bogdanovich was offered the chance to make

his first feature with the following proviso: he had horror

legend Boris Karloff for two days, twenty minutes of footage

from Corman's own The Terror (starring

Karloff) to incorporate, a budget of just $125,000 ($25,000

of which was earmarked for Karloff) and the rest was up

to him. Which brings us neatly back to the aforementioned Charles Whitman,

whose story was to prove a major influence on Bogdanovich's

film.

Karloff

plays Byron Orlock, an ageing horror star who unexpectedly

announces his retirement because he no longer believes that the period genre tales in which he appears can compete with the true life

horrors of modern society. As if to prove his point, outgoing young

family man Bobby Thompson unexpectedly kills his wife and mother

and takes off with an arsenal of guns, which he uses to

randomly shoot at drivers from the top of a gas storage tower, continuing his spree later at the very drive-in movie theatre at which Orlock is scheduled

to make a personal appearance.

Bogdanovich

connects the two stories at an early stage with a brilliantly

executed chance encounter: as Orlock stands on the sidewalk

cursing the changing times, there is a startling cut to

the image of his head framed in the crosshairs of a rifle

scope. An assassination attempt? No, the rifle is being

held by Bobby in the gun shop opposite and he's just getting

a feel for the weapon before buying it. He doesn't even

recognise the man he has taken aim at – it's the gun shop

owner who identifies Orlock. Despite this ominous introduction,

Bobby is presented from the start as a friendly all-American boy – cheery, good-looking and polite, you could be be forgiven for thinking that he seems the very essence of

responsible gun ownership. But just a few seconds after purchasing the rifle,

he walks to his car and opens the trunk to reveal a terrifying

array of weaponry, all laid out in a compulsively neat display

of potentially lethal firepower. We don't know exactly what,

but something is clearly wrong here. The strength of the

film's portrayal of Bobby is that he is never presented

as obviously unhinged – he cheerfully interacts with his

family, shares a meal and stories of his day ("I saw

Byron Orlock!"), and treats all of them with obvious

love and respect. But increasingly the chinks begin to show:

he arrives home one day and looks around him like he has never

been there before; an attempt to explain to his wife how

feels falls on deaf ears because she is busy

changing for work; and when target shooting he momentarily takes aim at his own father, who loudly admonishes

him about the irresponsibility of his actions. Then, one night, he collects

an automatic pistol from the trunk of his car and takes

it into the house and you know he is only a few steps away

from something terrible.

The

killing of Bobby's family and a delivery boy who's picked the worst time

to call at the house is a genuinely shocking act, carried

out without fuss or emotion. After briefly surveying his work, Bobby cleans up the blood and almost dutifully

places the bodies of his wife and mother in their beds.* When he takes up position on

the gas tower, there is no sign that he has been emotionally

affected in any way by his actions, and after neatly laying

out his guns he pulls out a sandwich and a coke as if on a leisurely duck hunting trip, before randomly taking aim at passing

motorists on the nearby freeway. That these sequences remain

so powerful is down to a deft blend of performance and

technical handling. The presentation is disarmingly matter-of-fact, with no music score or dramatic camera

placement to artificially heighten the menace or tension, and actor Tim O'Kelly, with his good looks and yearbook smile, hits absolutely the right note as Bobby,

never allowing the character's calm resourcefulness to descend

into obvious psychosis, the only exterior sign that anything

is wrong being his almost obsessive chocolate

bar snacking (a reference to White's 'Twinkie defence' perhaps?).

Orlock's

story runs consistently parallel as he hangs out with young director Sammy Michaels (played by Bogdanovich) and

his girlfriend Jenny, who is also Orlock's personal assistant. As Bobby's

story builds to a life-changing climax, Orlock is heading

in the opposite direction. His film career is effectively over, the movies he appears in are weak, and he no longer believes in himself as an actor.

His timing dismays Michaels, whose latest script is designed

specifically to re-invent the careers of both men, but Orlock

won't even read it, despite the high regard in which he

holds its writer. There is an intriguing degree of layering

to these scenes created in part by the casting. As ageing

horror star and ambitious young director respectively, Karloff

and Bogdanovich are playing direct reflections of their true-life personas, and the script Michaels wants Orlock to read

sounds very much like the one for this very film – "I

wrote a hell of a picture for you," Michaels tells

Orlock, "For you as you really are."** But to

assume that by playing a character close to his true self

Karloff is somehow slumming it would be way off the mark.

His performance here is a joy, a beautifully pitched melding of

English politeness and convincing world-weariness that is carried

off with a charm and subtlety that not only makes Orlock

sympathetic and engaging, but gives rise to some delicious character moments: the slight pause and eye-roll he gives at the drive-in when he suggests that they wait for Michaels' arrival by actually watching the film; his post-drinking start at catching himself in the mirror; the camp-fire horror tale with which he entrances his younger companions.

The two stories dovetail seamlessly at a climax (both parties arrive at the drive-inthrough logical and believable plot development), which retains to this day an astonishing sense of terror

in the dark, the traditional figure of the murderous bogeyman

brought starkly into the modern age as victims are selected

almost at random and killed at a distance, their deaths

preceded by a sharp intake of breath, and a gunshot drowned

out by the soundtrack of the movie. This collision of

stories peaks in an extraordinary confrontation

between the two men, where a confusion of reality and film prompt

the only real panic that Bobby ever displays. The last words

of both men are memorable, as Orlock reflects on his own

fears, while Bobby is more concerned with the accuracy of his shooting.

It's

a hell of a finale to a film that transcends its low budget and B-movie origins, and which stands today as one of the most intelligent,

gripping thrillers of its era, and one that is both still relevant and, by today's standards at least, a model

of impact through restraint. Others will disagree, but for

my money Targets showcases both Karloff

and Bogdanovich at their very best. There's a down

side to this, of course, both for an actor who could have shone brightly in

his later years if he had been offered more such roles,

and for a director just starting out who, despite some strong

work in the following few years, would never make a film

of such breathtaking immediacy again.

Framed

1.78:1 and anamorphically enhanced, this is a solid transfer,

recreating the film's specifically designed colour scheme

(warm colours for Orlock's scenes, colder colours for Bobby)

well, with contrast and black levels pretty much bang on.

There are a few dusts spots and dirt marks here and there,

but otherwise the print is in good shape, and certainly

looks a lot better than the tiny budget would lead you to

expect.

The

Dolby 2.0 stereo soundtrack is not the most dynamic on the

block and does show its age in that respect, though dialogue

and sound effects (there is no music score) are still very

clear.

The

main extra here is a Commentary

by director Peter Bogdanovich. An early member of what came

to be known as the Film Generation, directors who learned

their craft by watching and studying the films of their

cinematic heroes, Bogdanovich was also a writer for film

magazines and had interviewed and even made friends with

many of the film-makers he admired. There are thus a fair

few tales of how he put their advice into practice, something

many working in film nowadays will probably identify with

(fellow reviewer Camus, a working editor and occasional

director, freely admits that one of his own rules of editing

was learned from Hitchcock), but there is plenty of other

information offered up, from the illegal freeway filming

and the lies told to gun shop owners about the film's story,

to the links to (and quotes from) the Charles Whitman case.

He clearly loved working with Karloff, and pays tribute

to sound editor Verna Fields – who went on to cut Medium

Cool, Paper Moon, Sugarland

Express and Jaws – and assistant

director Frank Marshall, who later became a producer

and director of considerable note, plus later M*A*S*H

regular Mike Farrell, unrecognisable in his first film role

as the a drive-in shooting victim. But the most surprising

revelation is that his script was essentially re-shaped

into its present form by the late, great Samuel Fuller,

who refused to take credit for his work but was clearly

the brains behind some of the film's most memorable moments.

There

is also an Introduction by Peter

Bogdanovich, or at least that's what it's called here –

it's actually more an overview of the project, a compressed

version of the commentary that, though interesting in itself,

essentially repeats information supplied there. It's definitely

not one to watch before seeing the film for the first time.

How

can I be even remotely objective about Targets?

When I first caught it, many years ago, I was stunned. I

had come at Bogdanovich's work from the wrong direction,

from Nickelodeon and At

Long Last Love – neither of which I enjoyed – only later catching up with Paper

Moon and The Last Picture Show.

I could not believe that Targets was made

by the same director, and at the very start of his career.

Years later, presented so well on DVD, it stands the test

of time magnificently, shaming later films in its subtle

handling of a potentially sensationalist subject, in the process bringing

a real sense of horror to a story dragged almost literally

from the headlines. The presentation on Paramount's region

1 DVD is very good, and though I have not been able to check,

the region 2 release is apparently identical. Either way,

genuinely essential outsider cinema.

*

This was based on reports of Charles Whitman's actions after

killing his wife and mother.

**

This set-up also plays as a (probably accidental) reading

of the horror genre as it stood circa the film's release,

Orlock's career reflecting the decline of the once-dominant

Hammer studios, whose seemingly endless reworking of their

classic monster series was seen as increasingly out of touch

with an audience that was becoming tuned to the contemporary

urban horrors of Repulsion, Rosemary's

Baby and Night of the Living Dead.

|