[Note: the following review contains major spoilers. If you’re new to the film and know little about it, I’d skip to the final paragraph, or click here to do so automatically.]

| |

'It’s out of control. Anytime there’s a massacre, which is almost yearly now,1 we say, “Well, it’s not the guns. Guns don’t kill people. People kill people” and all that bullshit from the NRA. Politicians are afraid to touch it because of the right wing. And nothing ever changes. We’re living in the Wild West.” |

| |

Targets director Peter Bogdanovich in The Hollywood

Reporter, 25 July 2012, five days after a mass shooting

at a movie theatre in Aurora, Colorado,2 |

And yes, that’s still a favourite claim, that guns don't kill people, people kill people. But when so many of those people use guns to do it, this particular form of weaponry – whose primary purpose is to maim or kill, after all – has to shoulder part of the blame. The issue of easy availability of firearms in America has been a contentious one for as long as I can remember, and any politician who makes gun control a campaign promise is usually deemed to be committing electoral suicide. The debate has been regularly highlighted by a seemingly endless series of shootings at American schools, and was pushed into the mainstream back in 2002 by Michael Moore and the international success of Bowling for Columbine. But guns of all descriptions remain freely available, and people continue to die on a daily basis at the hands of those exercising their constitutional right to bear arms.

Since its early days, cinema has glamorised and even trivialised the gun. In films, it's a prop, a tool employed to both complicate and resolve a narrative thread. If you get shot in the movies, you fall down, maybe you bleed a little, and you drop out of the story. Wielded by the good guys, guns are seen as tools for justice, and if they are used to kill the innocent, then it's because they have fallen into the hands of the wicked, the naïve, or the mentally unhinged. This allows those who believe in an unconditional reading of the Second Amendment to remain comfortable with the free availability of such deadly weaponry – killing sprees are executed by insecure and mentally unstable loners with a grudge or a loose screw, people unlike them or anybody that they know. Guns don't kill people, the socially excluded do.

This oft-cited claim was contradicted somewhat in 2018 in a study authored by criminal justice professor James Silver of Worcester State University, and Supervisory Special Agent Andre Simons and researcher Sarah Craun of the FBI’s Behavioral Analysis Unit.3 In the process of examining 160 mass shooting incidents between 2000 and 2013, the investigators found that the majority of the active shooters were not loners at all, but individuals with a clear social connections to others. Then on 4 January this very year, as if to hammer the point home, 42-year-old Michael Haight killed seven members of his own family – his wife, his mother-in-law, and five children – before turning the gun on himself. And he’s far from the first such notorious example of a seemingly ordinary (and usually male) individual who one day picked up a gun and unleashed deadly mayhem.

On 31 July, 1966, former Eagle Scout and ex-U.S. Marine Charles Whitman stabbed his wife and mother to death. The following day, he took a sniper rifle and climbed the Bell Tower at the University of Texas, and in the space of 96 minutes killed 16 people and wounded a further 33, before being killed himself when armed officers stormed the building.

On 27 November, 1978, former policeman and San Francisco city supervisor Dan White, a well-liked man from what the well-to-do like to describe as a good background, entered City Hall and shot Mayor George Moscone, then walked into the office of supervisor Harvey Milk, the city's first openly gay official, and emptied five bullets into him. Both victims died of their wounds. White was sentenced to a mere seven years and eight months and served less than five. The gun he used was not considered to be an issue, White's lawyer contesting instead that a diet of junk food – the notorious 'Twinkie defence' – was responsible for his 'out-of-character' behaviour.

On 27 July, 1999, 44-year-old former day trader Mark Orrin Barton bludgeoned his wife to death as she slept, and the following day did likewise to his two children. The day after, he entered the offices of his former employer, Momentum Securities in Atlanta, Georgia, and chatted with his former co-workers before pulling out a gun and killing four people and attempting to murder a fifth. He then broke into the nearby All-Tech Investment Group building and fatally shot five more victims before departing and later taking his own life.

On 1 October, 2017, 64-year-old former auditor and real estate businessman, Stephen Paddock, rented a suite on 32nd floor of the Mandalay Bay hotel in Las Vegas, from where he opened fire with a variety of semi-automatic rifles on the crowd attending the Route 91 Harvest music festival on the Las Vegas Strip. Before killing himself he fired over 1,000 rounds, killing 60 people and wounding over 400 more. The resulting panic brought the total number of injured to over 860. This remains the deadliest mass shooting in American history.

Depressingly, I could go on for some considerable time. Already this year there have been over 500 recorded mass shootings4 in America alone, many of them carried out by socially integrated individuals. And yet movies continue to assure us that it's those on the fringes of society that guns turn into killers. Even Thomas Vinterberg and Lars von Trier’s 2005 Dear Wendy, an otherwise intelligent and well-made film, chose to explore the danger of developing an obsession with firearms by placing them in the hands of those that society likes to categorise as misfits and losers. You could be forgiven for wondering when a filmmaker would be bold enough to show that even the most upright, clean living American boy could, with free access to a variety of firearms, turn without warning into a mass murderer. As it happens, you don't have to wait at all, but take a trip back to 1968 and Peter Bogdanovich's astonishing first feature, Targets.

The story of how the film went into production at all has become part of film history (you’ll hear and read it retold many times in the special features that accompany this disc). Having rewritten and directed some sequences of Roger Corman's 1966 The Wild Angels, Bogdanovich was contacted by Corman and offered the chance to make his first feature, with the proviso that he had horror legend Boris Karloff for two days, twenty minutes of footage from Corman's period horror The Terror featuring Karloff to incorporate, and a budget of just $125,000, $22,000 of which was earmarked for the star. What he did with it otherwise was up to him. Bogdanovich developed the story with his then wife Polly Platt, and fashioned this into a working screenplay with considerable uncredited assistance from renowned writer-director Samuel Fuller. All of which brings us neatly back to the above-mentioned Charles Whitman, whose actions were to prove a major influence on Bogdanovich's film.

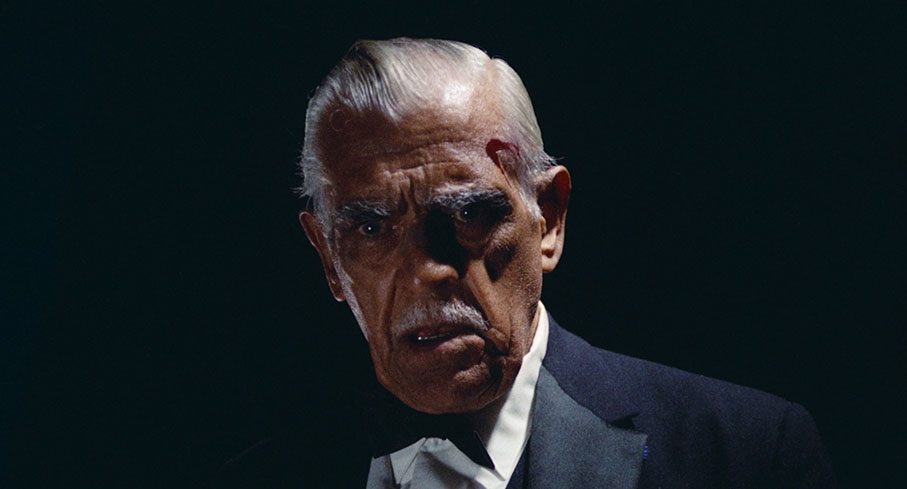

Karloff plays Byron Orlock, an ageing horror star who unexpectedly announces his retirement because he no longer believes that the increasingly creaky period genre tales in which he appears can compete with the true-life horrors of modern society. As if to prove his point, outgoing young family man Bobby Thompson (Tim O'Kelly) unexpectedly murders his wife and mother and takes off with an arsenal of legally owned guns, which he uses to randomly shoot at drivers from the top of a gas storage tower. When the police arrive, he makes his escape and gives them the slip by ducking into the drive-in movie theatre at which Orlock is scheduled to make a personal appearance that evening, then climbs up the scaffolding behind the screen and prepares for his next set of killings.

Bogdanovich connects these two stories at an early stage with a brilliantly executed chance encounter. As Orlock stands on the sidewalk cursing the changing times, there is a startling cut to the image of his head framed in the crosshairs of a rifle scope. An assassination attempt, perhaps? The close-up of the potential shooter’s eye and the tightening of his finger on the trigger certainly seems to suggest so. Yet it turns out that the rifle is being held by Bobby in the gun shop opposite, and he's simply getting a feel for the weapon before buying it. He doesn't even recognise the man he has taken aim at – it's the gun shop owner who identifies Orlock.

Despite this ominous introduction, Bobby is presented from the start as a friendly all-American boy – good-looking, polite, and energetically upbeat, you could be forgiven for thinking that he seems the very picture of responsible gun ownership. But immediately after purchasing the rifle, he walks to his car and opens the trunk to reveal a genuinely terrifying array of weaponry, all laid out in a compulsively neat display of potentially lethal firepower. We may not know exactly what at this stage, but something is clearly wrong here. Yet a strength of the film's portrayal of Bobby is that he is never presented as obviously unhinged – he cheerfully interacts with his family, shares a meal and stories of his day ("I saw Byron Orlock!"), and treats them all with open love and respect. But increasingly the chinks begin to show: on arriving home one day, he looks around him as if he has never been in this house before; an attempt to come clean to his wife Ilene (Tanya Morgan) about the “funny ideas” he has been having falls on deaf ears because she is busy changing for work; and when target shooting one day he momentarily takes aim at his own father (Arthur Peterson), who angrily admonishes him over the reckless danger of his actions. Then, one night after his parents have gone to bed, he collects an automatic pistol from the trunk of his car and takes it into the house, and you just know that he is only a few steps away from something terrible.

The killing of his wife, his mother and a groceries delivery boy who has picked the worst time imaginable to call at the house is genuinely shocking, carried out as it is without fuss or emotion, after which Bobby calmly locks the doors, covers and cleans up the blood stains, and almost dutifully places the bodies of his wife and mother in their beds.5 When he takes up position on the top of the gas tower, there is no sign that he has been emotionally affected by what he has done, and after neatly laying out more guns than he could possibly need, he takes out a sandwich and a coke as if on a leisurely duck hunting trip, before randomly taking aim at passing motorists on the nearby freeway. That these sequences remain so powerful is down to a deft blend of performance and technical handling. The presentation is disarmingly matter of fact, with no dramatic camera placement or music score (the only music heard throughout the film is heard playing on radios) to artificially heighten the menace or the tension, while actor Tim O'Kelly, with his good looks and yearbook smile, hits absolutely the right note as Bobby, never allowing the character's calm resourcefulness to descend into obvious psychosis, the only exterior sign that anything is wrong being his almost obsessive chocolate bar snacking (a reference to Dan White's 'Twinkie defence' perhaps?).

Orlock's story runs consistently parallel as he hangs out with young writer-director Sammy Michaels (nicely played by Bogdanovich himself) and Sammy’s girlfriend Jenny (an engagingly confident Nancy Hsueh), who is also Orlock's personal assistant. As Bobby's story builds to a life-changing climax, Orlock is heading in the opposite direction – his film career is effectively over, the movies he now appears in are weak, and he no longer believes in himself as an actor. The timing of his decision to retire dismays Michaels, whose latest script is designed specifically to re-invent the careers of both men, but Orlock won't even read it, despite the high regard in which he holds its author. There is an intriguing degree of layering to these scenes – as ageing horror star and ambitious young director respectively, Karloff and Bogdanovich are effectively playing fictional versions of their true-life personas, and the script Michaels so desperately wants Orlock to read sounds very much like the one for this very film – "I wrote a hell of a picture for you," Michaels tells Orlock, "for you as you really are."6 Yet, to assume that by playing a character close to his true self Karloff is somehow slumming it would be way off the mark. His performance here is a constant joy, a beautifully pitched melding of English politeness and convincing world-weariness carried off with a charm and naturalism that not only makes Orlock sympathetic and engaging, but gives rise to some delicious character moments: the slight pause and eye-roll he gives at the drive-in when he suggests that they wait for Michaels' arrival by actually watching the film; his (apparently improvised) post-drinking start at catching sight of his own reflection; the gorgeous, single-shot recitation of an old fable with which he entrances his younger companions.

The two stories dovetail seamlessly at a climax, with both parties arriving at the drive-in-through logical and believable plot development. It’s a sequence that retains to this day an astonishing sense of terror in the dark, the traditional figure of the murderous bogeyman brought starkly into the modern age, as victims are selected almost at random and killed at a distance, their deaths preceded by a sharp intake of breath, and the gunshots drowned by the soundtrack of the movie.7 This collision of stories peaks in an extraordinary confrontation between the two men, where a confusion between reality and projected film prompt the only real panic that Bobby ever displays. The last words of both are memorable, as Orlock reflects on his own fears, while Bobby is more concerned with the accuracy of his shooting.

It's a hell of a finale to a film that transcends its low budget and B-movie origins, and which stands today as one of the most intelligent, gripping and incisively directed thrillers of its era, and one that not only remains tragically relevant today, but by modern standards is a model of impact through restraint. Others will disagree, but for my money Targets showcases both Karloff and Bogdanovich at their very peak, and while I can’t help wondering how much more brightly Karloff would have shone in his later years had he been offered more such substantial non-horror roles, you frankly couldn’t ask for a better swan song than the one that Bogdanovich and his collaborators gifted him here. For the film’s Hungarian cinematographer, László Kovács, who had previously worked primarily in low-budget exploitation cinema, this marked a turning point that the following year would see him move into the big leagues following his work on Dennis Hopper’s landmark independent film, Easy Rider. It also launched the career of Polly Platt, whose later films as a production designer include three of Bogdanovich’s most acclaimed works, while as a producer she later oversaw the first film of another future director of note with the 1996 Bottle Rocket, the debut feature of a certain Wes Anderson. Bogdanovich, of course, went on to become a filmmaker and film historian and scholar of considerable repute, with his second feature, the 1971 The Last Picture Show, now widely championed as an American classic. Yet while I greatly admire some of his subsequent work, for me Targets remains unquestionably my personal favourite. Beautifully directed and superbly acted, it’s a work of breathtaking immediacy, impact and searing socio-political relevance, and without question one the most striking debut features in twentieth century American cinema.

The original 35mm negative of Targets was scanned in 4K resolution by Paramount Pictures, and is presented on this Blu-ray in 1080p in its original aspect ratio of 1.85:1. The result is a consistently impressive transfer that copes well with the film’s varying lighting conditions, particularly the drive-in theatre climax, which includes shots of cars that were filmed at night in almost documentary fashion as tests of film stock low light tolerance but included in the final cut of the movie. Although a tad strong on a handful of shots (again due primarily the lighting conditions), the contrast is otherwise well balanced, with the black levels rock solid when required (the shots of Bobby sitting in the dark lit only by the TV or a cigarette lighter). The film’s pastel-leaning colour palette is also nicely reproduced, perfectly capturing the use of warm colours for Byron and cool tones for Bobby of Polly Platt’s production design and László Kovács’ lighting. It’s a subtle technique that reaches a peak in a wide shot of cars during the film’s final seconds, where two panels of the background fencing are lit in these alternate colours – when the characters finally meet, so do their assigned hues. As expected, the image is clean and free of damage, and a fine film grain is visible throughout.

The Linear PCM mono soundtrack has some unsurprising range restrictions, but the dialogue and sound effects are clearly reproduced and display no distortion. There is no score, but the diegetic music heard on radios is appropriately pitched towards the tinny treble of the radio technology of the day. No background fluff or other signs of wear are evident.

Optional English subtitles for the deaf and hearing impaired have been included.

Audio commentary by director Peter Bogdanovich (2003)

An early member of what came to dubbed the Film Generation – directors who learned their craft by watching and studying the movies of their cinematic heroes – Bogdanovich has also worked as a writer for film magazines, and had interviewed and even made friends with many of the filmmakers he admired. There are thus a fair few tales here of how he put their advice into practice, but there is plenty of other detail provided on the making of Targets, from the illegal freeway filming and the lies told to gun shop owners about the film’s subject matter to the links to (and quotes from) the Charles Whitman case. He clearly loved working with Karloff, and pays tribute to sound editor Verna Fields – who went on to cut Medium Cool for Haskell Wexler, Paper Moonfor Bogdanovich, and Sugarland Express and Jaws for Steven Spielberg – and assistant director Frank Marshall, who later became a producer and director of considerable note. A fine and informative inclusion sourced from 2003 Paramount DVD release.

Audio commentary by film historian Peter Tonguette

In this new commentary, critic, journalist, and author of the book Picturing Peter Bogdanovich: My Conversations with the New Hollywood Director, Peter Tonguette, lays his cards on the table from the off by describing Bogdanovich as the most talented American director of his era. It’s thus unsurprising that he misses no opportunity to praise Bogdanovich’s direction here, but the examples he highlights, despite very occasionally leaning towards hyperbole, are hard to argue against, and while there is some content that you’ll find duplicated in other special features, Tonguette also makes some pertinent observations of his own about the film. Amongst the subjects covered are the expressionistic use of colour, the staging of the actions scenes, the absence of a music score, the lingering on victims during the climax, the performances of the lead actors (Bogdanovich included), and plenty more. Having interviewed Bogdanovich several times, he quotes him on a number of points, as well as an enthralling sounding contemporary review by Renata Adler, and signs off by describing the film as, “one of the most startling, suspenseful, and most sombre films Peter Bogdanovich ever made.”

Targets: An Introduction by Peter Bogdanovich (13:41)

Also sourced from the 2003 Paramount DVD release, this is less an introduction than a reflective overview of the project that, while most definitely of real interest in itself, does cover areas explored in more detail by Bogdanovich in his commentary track. Due to plot points discussed, it’s definitely not one to watch before seeing the film for the first time, but once you have watched it, this would make for a good first port of call.

Hitting Targets: Sara Karloff on Her Father, Boris (40:07)

Boris Karloff's daughter Sara won me over in a heartbeat with her opening proclamation that Targets is her favourite of her father’s many films. She then goes on to outline in some detail why this is the case, emphasising just how much respect Karloff had for its talented young director and how the film reflected how own views of the time. She looks back at her father’s formative years and how a lifelong love of acting saw him diverge from the career direction followed by his siblings and lie his way into a theatre company before eventually moving into bit parts in movies. She recalls how advice given to him by the great Lon Chaney eventually bore fruit in Frankenstein, and details the two weeks he spent with Jack Pierce to help him develop the monster’s now iconic make-up, as well as the three hours it took to put it on and take it off each day. She confirms that he abhorred prejudice of any kind, which led in part to him becoming one of the founding members of the Screen Actors’ Guild, a risky move to unionise the profession at a time when the studios had the power to instantly finish a performer’s career. There are many other enjoyable and fascinating stories here, and the American-accented Sara has fond memories of her father’s Englishness, from his dry wit to his love of cricket and gardening.

On Target: Boris Karloff in the 1960s (16:47)

Stephen Jacobs, author of Boris Karloff: More Than a Monster, looks back at Karloff’s final decade of movie acting, opining that two of the films he made during that period – Targets and Michael Reeves The Sorcerers (1967), both of which were helmed by new young directors – are amongst his very best. He notes that Karloff liked even the monsters he played to have a sympathetic moment, that he loved working with Mario Bava on the 1963 Black Sabbath [I tre volti della paura], and had a particular fondness for a sequence that’s only in the Italian version of that film. His coverage of Targets, though interesting in itself, does unknowingly rerun stories told elsewhere, so how fresh it seems will depend on which special feature you elect to watch first.

Gentleman of Horror (8:08)

A rather nice revelation in this video essay by the BFI’s Vic Pratt occurs towards the end, when he reveals that Karloff’s gentlemanly demeanour saw him always referred to as “Uncle Boris” in the Pratt household, despite there being no familial connection (as I’m sure you all know, Karloff’s real name was William Henry Pratt). He talks about the birth of cinematic horror, the modern subtextual aspect of Targets, and Karloff’s own discomfort with his genre pigeonholing. He also cannily notes that the true horror of Targets is that its motiveless killer could be anybody.

Trailers From Hell: Targets (2:48)

Filmmaker Joe Dante introduces the film’s re-issue trailer, then reads from a pre-prepared script (the literary sentence structure gives this away), noting that Bogdanovich had a serious leg-up at the Roger Corman film school due to the industry connections he had already made, and that he regretted making the film after the Colorado movie theatre massacre. Dante nonetheless proclaims that Targets is “one of the best debut films ever made by an American director.” No argument here.

The Guardian Interview: Peter Bogdanovich (41:48)

Recorded at London’s National Film Theatre (now BFI Southbank) in February 1972, this onstage chat with director Peter Bogdanovich appears to have been held following one screening of Targets and shortly before a second (they have to round things up because patrons are waiting to get in). Bogdanovich is a witty storyteller, particularly when he has an audience as he does here, and entertainingly recounts how shooting sequences of Roger Corman’s The Wild Angels led to the offer to direct his own film, the conditions of which you’ll hear outlined several times in the special features. Other areas covered include his belief that all of the good movies have been made (going to have to disagree with you on that one, sir), the odd but also oddly pragmatic studio practice of paying people not to make movies, the partly practical reasons for shooting The Last Picture Show (1971) in black-and-white, working with Boris Karloff (“a lovely man, very kind to me and generous”), acting in his own film (“I cringe a little bit looking at it now”), and more. Audience questions are invited, but the recordings of these lectures were originally made for archive purposes only, so it’s hard to make out what is being asked, though many of the questions are handily repeated either by Bogdanovich or his unidentified interviewer. When asked about the difference between the low-budget filmmaking of Targets and the far bigger budgeted What’s Up, Doc? (1972), he amusingly claims that Barbara Streisand’s trailer on the later film cost more than Targets did in its entirety.

The Guardian Interview: Roger Corman (64:07)

Having attended an onstage interview with Roger Corman at the National Film Theatre in London many years ago, I had a particular interest in this inclusion. As it turns out, this interview was recorded in 1970, about 10 years before the one that I attended as an eager teenager, and shortly after Corman had completed his epically (and, as it turns out, provocatively) titled science fiction comedy-drama, Gas! -Or- It Became Necessary to Destroy the World in Order to Save It. As was common at the time, Corman is introduced and interviewed by an unidentified male host with a very English upper-middle class accent, one who asks some of the longest questions I’ve yet heard posed at such an event, At one point he also refers to some of Corman’s works as “silly,” which the genial director responds to with more grace than I probably would have in his position. Corman, as ever, is a delight to listen to, in part because he has the silkiest voices, but mainly because he’s such a smart and dryly witty storyteller, and by this point in his career he had a wealth of independent filmmaking experience to draw on. Subjects covered include an explanation of the real-world horror behind full title of the above-mentioned Gas!, the impossibility of getting studio funding for his powerful 1962 anti-racist drama The Intruder (aka The Stranger) at a time when he could get almost any project greenlit, being taken seriously as a film artist by French critics (“This is how it should be”), the art of making films quickly on minimal budgets, and more. He fascinatingly equates the build-up and release from a well-executed moment of cinematic horror to the sexual act, confirms that he tries to do the best job possible whatever the project, and when asked to pick his favourites of his Poe films, he is unexpectedly dismissive of the interviewer’s choice, The Tomb of Ligeia (a film I’m also very fond of), though I do appreciate his reasoning on this. As with the Bogdanovich interview detailed above, this recording was originally made for archive purposes only, and while Corman’s words are always clear, you’ll need far better hearing than mine to make out the audience questions, despite an attempt to push the volume up in post-production that reveals a most curious but persistent and distracting noise that sounds a little like someone tapping twice on a bongo every few seconds.

Image gallery (6:17)

A rolling image gallery consisting of seven behind-the-scenes photos, 33 promotional stills (the grain and lack of pin-sharpness on many of these, together with angles that mirror exactly what plays out on the screen, suggest blow-ups from the film’s negative rather than separately shot photos), six screen of lobby cards, seven promotional ads of similar design, four posters, (including one advocating gun control that would have right-wingers throwing their toys out of the pram these days), and four photographic portraits of Boris Karloff, including one with his then wife Evelyn.

Booklet

This 34-page booklet opens with introduction by Boris Karloff’s daughter Sara, who reminds us that this was her favourite of her father’s 160-odd films. This is followed by a nicely concise essay on the film by writer and curator Jason Wood, who echoes my own view when he states early on, “Viewed today, even accounting for The Last Picture Show, there is a pervading sense that Bogdanovich never again made anything half as remarkable.” Next up, author Stephen Jacobs, whose books include Boris Karloff: More Than a Monster and The Karloff Compendium, takes a more detailed look at the making of the film, bringing together information found elsewhere in the special features into a single tidy essay. Film writer and lecturer Ellen Cheshire spreads her net a little wider with a concise overview of how Boris Karloff rose to fame in the early sound era, and how the post-Hays Code emergence of a new generation of filmmakers led to him and Peter Bogdanovich collaborating on Targets. Credits for the film are followed by a detailed essay on it by writer Peter Tonguette – inevitably there is some crossover here with his commentary and even other essays in this booklet, but this still makes for consistently interesting and thoughtful reading. Credits for the special features and details on the transfer are also provided.

What more can I say? An extraordinary first feature and one of my very favourite films gets a glorious Blu-ray release from the BFI. A first-rate restoration and transfer is backed by a phenomenal collection of superb quality special features that should keep enthusiasts for the film busy for several evenings. Just excellent. Very highly recommended.

1. In a sobering illustration of changing times, mass shootings in America have since become an almost a daily occurrence: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_mass_shootings_in_the_United_States_in_2023\

2. https://www.hollywoodreporter.com/movies/movie-news/dark-knight-rises-shooting-peter-bogdanovich-353774/

3. https://www.motherjones.com/crime-justice/2018/06/active-shooters-fbi-research-warning-signs/

4. For the record, the official definition of a mass shooting is summarised in Wikipedia, “a violent crime in which an attacker kills or injures multiple individuals simultaneously using a firearm.” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mass_shooting

5. This was based on reports of Charles Whitman's actions after killing his wife and mother.

6. This set-up also plays as a (probably accidental) reading of the horror genre as it stood circa the film's release, Orlock's career reflecting the decline of the once-dominant Hammer studios, whose seemingly endless reworking of their classic monster series was seen as increasingly out of touch with an audience that was becoming tuned to the contemporary urban horrors of Repulsion, Rosemary's Baby and Night of the Living Dead.

7. The sequence has taken on an even greater sense of real-world terror following the mass shooting at a movie theatre in Aurora, Colorado that left 12 people dead and 70 others injured, 58 of them from gunfire. The incident caused Bogdanovich at one point to state that it sickened him that he had ever made this movie.

|