"You see so many movies... the younger people who are coming

from MTV or who are coming from commercials and there's no sense

of film grammar. There's no real sense of how to tell a story visually.

It's just cut, cut, cut, cut, cut, you know, which is pretty easy." |

Director and Cinephile, Peter Bogdanovich |

In the pre-digital age when movies were still ignorantly but happily mired in reality and physics, and post production was almost mostly physical labour (film weighs quite a bit, trust me), there was a craft to the art of narrative that was subtly different to the way stories are told today. It's not all "cut, cut, cut," these days but Bogdanovich can be forgiven in thinking that the lunatics have really taken over asylum; running with scissors, you might say. Sometimes, they are brilliantly talented lunatics, no question, but there is something almost indefinable missing from mainstream movies today. It pops up occasionally in an Imitation Game or a Theory of Everything – craft at the forefront of the storytelling, an almost cosy sense (and I am aware of how that could be negatively perceived) that we are in the hands of a filmmaker who is providing satisfaction at each click of the story gear wheel. I'm not saying that this aspect always makes for a compelling 'must see' experience but then cinema's scope is as wide as a seashore horizon. Sometimes the heartwarming story about the relationship of a bereaved child who goes on the road to con people with a man who may be her father is as charming as they come. Looked at in 2015, the film has its startling moments – perhaps no raised eyebrows in 1973 but my forehead got vertigo on several occasions. And this was the first movie I ever 'saw' as a comic parody before I got to see the actual film.

You may not have heard of Mad magazine (my God, is it still with us? It is, wow, still being published after 63 years). Think of it like a pre-TV Daily Show or Have I Got News For You with added cartoon and movie parodies. I was first exposed to brilliant and excruciatingly bad puns via this US import and it was in the pages of a 1974 issue, that I first 'saw' Paper Moon. I still remember the artwork even though I can't find any examples of the actual inside of the mag on the web though I am tempted to pick up a physical copy from eBay. The caricatures were brilliantly rendered, the characters acutely recognizable from their exaggerated features. The plot of Paper Moon is, naturally, paper-thin. It's centred on a precocious nine-year-old girl, Addie Loggins (beautifully and instinctively played by Tatum O'Neal) who has lost her mother. Not exactly overwhelmed by friends and family at the funeral, she meets a man who shiftily steals flowers from another plot (as in headstone not story) and throws them into the mother's grave with a nonchalance that belies what feelings he may have had for the poor woman. Those at the graveside, those responsible men and women in authority decide to brow beat the man (Moses Pray, played by Tatum's father and a big star at the time, Ryan O'Neal) into taking the girl to her aunt a few states away. 2015 face palm number one. A strange man turns up the funeral of a woman who may or may not have been his ex-lover and he walks off with her nine-year-old daughter for many days of travel. OK. Pedophilia may have been consistently practiced in the world since time began (or at least until some idiot invented Catholicism) but it wasn't brought up in any conversation in the 70s. Moors murderers, Ian Brady and Myra Hindley were the only such topic in public discourse at that time and were such horrific aberrations they were the exception that proved the rule, the rule that people don't do that sort of thing, kill and molest children. So you have to accept that first fracture in our modern overly sensitive suspension of disbelief. And as we are now living in a fearful culture overegged ridiculously by the media, our reactions to this aspect of the film should be the ones to be under scrutiny, not the movie itself. Needless to say, it's a father-daughter dynamic all the way.

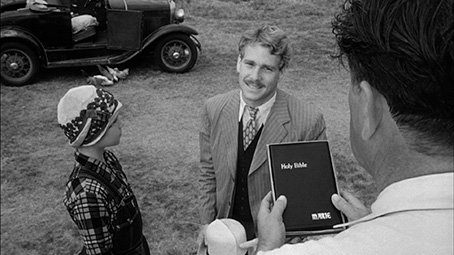

I neglected to mention, the film is firmly set in the Great Depression era of the American Midwest and southern states (it's set after the 1932 election as President Franklin 'Frank' Roosevelt is consistently name-checked) and its visual iconography is perhaps not so well known to a modern audience. This is America's dust bowl, small towns with inhabitants eking out a meagre living on the wrong side of the poverty line after a massive stock market crash in August 1929. Vast stretches of roads connect each dusty, isolated community and Moses Pray works them all. He is a lowly con man preying on bereaved widows who are led to believe that their recently deceased had ordered a Bible with their name printed on it (via a simple branding iron printing press). In offering to give the fictitious dollar refund back, he cons them into buying the damn things and off he goes on his merry. But he makes a mistake by starting his road trip with Addie by blackmailing the brother of the man who drove into and killed Addie's mother. He now has two hundred dollars in his pocket. Trouble is, it's technically Addie's money and she wants it back... and she isn't exactly shy about letting him know this simple fact.

This is the quintessential road movie. These are two mismatched characters thrown together by circumstance that start to understand that as a team they are stronger than they could be individually. When necessary, Tatum plays the poor stranded, bereaved little girl, behaviour that prompts all manner of sympathy from idiots who at that time had no chance of knowing better. Often mentally slower than his young charge, Moses soon gets into the swing of things and like all tempted on to the wrong path, he gets ambitious and criminal ambition is hard to keep hidden from those enthusiastically enforcing laws. Playing both brothers – the bootlegger and the police chief – is John Hillerman, well known to 70s TV audiences but especially to myself as the serene philosopher of Rock Ridge in Mel Brook's Blazing Saddles, Howard Johnson. In fact he sets up one of favourite lines of the movie... "Y'know, Nietzsche says: 'Out of chaos comes order'," to which comes the sensitive reply, "Oh, blow it out your ass, Howard." Hillerman's police chief makes life difficult for Moses and when the law doesn't apply, then fists do just as good a job of dissuading further criminality. Yes, that's a very young Randy Quaid in a 'wrassling' match with O'Neal for a car trade and you will recognise a few well known faces (if not names) from two decades of US TV imports to the UK. Madeline Kahn, the 70s go to girl for comic sexiness, plays Trixie Delight (so not a given name) who enthralls Moses but whose morals (and body) in the heady and brutal days of the Depression take a few tumbles.

Tatum O'Neal as Addie (and as an actress) is streets ahead of most in her profession when it comes to being able to do a particular thing convincingly. 2015 face palm number two. At nine years old, she smokes on screen utterly believably. She clearly takes the smoke in and exhales from her lungs not her mouth. Now having been an ex-smoker, nothing riles me more than actors filling their cheeks and blowing smoke out as if they think they know what it takes to be a smoker. Someone either gave her explicit direction (which would have had her sick on set – the first time you smoke, you get sick. You have to force your body to tolerate it inside your lungs). OK, you were probably tougher than me but the naturalness of her smoking has me uneasily believing the nine year old was already a seasoned smoker even then. Lung cancer is mentioned in the Mad magazine parody so it wasn't as if 70s audiences were unaware of the connection.* On the subject of smoking, there is a lovely moment when Moses stuffs a cigarette in his mouth and winces from swollen lip pain and smartly moves it over a little before lighting it. It's a tiny detail but an appreciated one.

Director Peter Bogdanovich was disgruntled at being the most successful director in the newly formed 'Directors Company' founded by Bogdanovich, William Friedkin and Francis Ford Coppola. The deal was that all three would share each other's profits. After Paper Moon made over ten times its budget and Coppola's superb but not successful The Conversation frankly didn't, Bogdanovich wasn't so thrilled with the arrangement. Friedkin didn't even get to make his movie before the company was disbanded, but a wonderfully entertaining tidbit of information got squeezed out doing a little research (OK, Wikipedia is not exactly investigative journalism). Coppola brought a script from his protégé to be considered as a project 'The Directors Company' might oversee and co-produce. Both Bogdanovich and Friedkin turned it down flat. Its title was Star Wars... Given that horrific lapse in the piercing light of hindsight, Paper Moon is still well worth a look if you can easily put up with a whimsical look at a father/daughter relationship with the backdrop of a very tragic and all too real event.

There's something hugely attractive about monochrome 35mm, but add some red and green filters to the mix to darken skies and enhance skin tones and it's hard to fall back in love with colour again. Such is the case with Paper Moon, an aesthetic that is wonderfully captured by the HD transfer here. The contrast is punchy, delivering coal hole blacks and an attractive tonal range, and the image boasts a sharpness that really brings out the textures in clothing, faces and background detail, which thanks to László Kovács' deep focus cinematography is every bit as clear as the foreground. The film grain is always visible and just occasionally more pronounced, but always feels right for the film stock and never feels artificially enhanced. As you would hope, there's hardly a dust spot to be seen, and there's not a trace of picture instability. The framing is 1.78:1, a slight crop from the original 1.85:1.

A clean and surprisingly crisp Linear PCM 2.0 mono soundtrack with impressively distinct rendering of dialogue (all except one shot was recorded live on location) and seductive rendering of the diegetic period tunes that stand in for a traditional music score. There is a faint hiss detectable on a couple of the quieter scenes, but you'll probably not notice it and it never interferes.

Optional English subtitles for the deaf and ghearing impaired are also included.

Peter Bogdanovich commentary

Recorded in 2005, this commentary by director Bogdanovich plays at times like an informative film school lesson, particularly his highlighting of how specific shots were used and why, as well as his thinking behind some of the longer takes, the decision to shoot in black and white and to strive for a depth of field that kept everything in focus. There's plenty on the actors, including some of those in key supporting roles, plus changes that were made to Alvin Sergent's screenplay, the advice he received from directors such as John Ford and Orson Welles, and a good deal more. I was intrigued to learn that Ryan O'Neal did all his own stunt driving, particularly given his later title role in Walter Hill's The Driver. A really useful inclusion.

The Next Picture Show (14:10)

Peter Bogdanovich looks back at how the film came to be and the process of bringing it to the screen, aided by contributions from production designer (and his ex-wife) Polly Platt and associate producer (and later director) Frank Marshall, who focus on the process of selecting and dressing the locations to suit the period. All interesting stuff, although there is some serious crossover with the commentary in places. There are also a couple of too-brief snippets of behind-the-scenes footage.

Asking for the Moon (16:30)

Comprised from material from the same interviews in the preceding featurette, there is some more crossover with the commentary here, but this is dwarfed by coverage of aspects not previously addressed. This includes a welcome contribution from cinematographer László Kovács on the technical aspects of red filtered monochrome and the lighting requirements for the film's seemingly infinite depth of field photography. Polly Platt reveals how she designed the hat in which money is hidden in plain sight (see the film to discover how well this works) and a dress for Madeline Kahn that made her breasts jiggle. There are also some priceless outtakes (O'Neal is an unexpected deadpan comedy joy here) and footage of Bogdanovich demonstrating how he wants his lead actor to approach a scene.

Getting the Moon (4:15)

Also built around the interviews used in the previous featurettes, this shorter piece looks at the film's release and popularity with the public and concludes with all concerned enthusiastically praising it. Best of all is another small collection of sometimes amusing outtakes. I could have done with a whole featurette on these.

Also included is a 36-page Booklet featuring a new essay on the film by Michael Brooke, rare production stills, and more, but we don't currently have a copy of this to comment on. Bound to be good, though.

Bogdanovich's third commercial hit in a row after The Last Picture Show and What's Up, Doc?, Paper Moon still impresses for the poetic economy of its storytelling, its technical handling, László Kovács' gorgeous deep focus monochrome cinematography, and its delightful lead performances, with Tatum O'Neal landing an Academy Award for her work here, making her (at the time) the youngest person ever to win an Oscar. As we've come to expect, Masters of Cinema's dual format release does the film proud, with a strong transfer and a small but well targeted collection of special features. Recommended.

* Slarek note: on the commentary track, Peter Bogdanovich reveals Tatum was smoking lettuce cigarettes (a form of herbal cigarette that contains no tobacco or nicotine) and that she learned to smoke authetically by immitating the way that Bogdanovich himself smoked. |