|

If you're under 30 years of age, there's a good chance you've never heard of Jimmy Boyle, Actually, if you're over 30 it's quite possible you've not heard of him either, unless you happen to have grown up in Glasgow in the 1960s. Back then Boyle was a notorious figure, a hard man in one of the city's most feared gangs who was once dubbed 'the most violent man in Scotland'. In 1967 he was arrested and convicted for the murder of local gangster Babs Rooney, and despite protesting his innocence of that particular crime, he was sentenced to life imprisonment. Almost from the moment of his incarceration, Boyle clashed with his custodians in a series of frequently violent confrontations, then in 1973 became one of the first prisoners to participate in an experimental rehabilitation programme at a special unit in Barlinnie Prison, one that was set to change the course of his life. It was here that Boyle wrote an autobiographical account of his prison experiences titled A Sense of Freedom, which in 1979 was made into a film for Scottish Television by screenwriter Peter McDougall and director John Mackenzie, who had just completed work on his London gangland masterpice, The Long Good Friday.

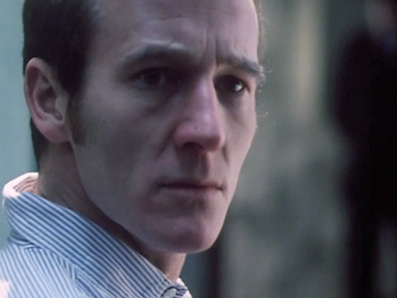

In McDougall and Mackenzie's film, our first close-up encounter with Boyle is one that effectively defines the allegiance tightrope we will be asked to walk for the rest of the film. At this point in his life Boyle was unquestionably a dangerous man, one seemingly unafraid of putting himself at risk and inflicting serious violence on anyone who stood in his way. His business model is defined here in just two shots, as he walks into frame, expensively dressed and flanked by two of his cronies, and takes a meaningful look at the remains of broken pub window being chiselled out of its frame, then approaches the downcast landlord with a cocksure walk and a barely suppressed smile. His intentions are confirmed when he remarks on the problems that the landlord seems to be having and suggests that he might be able to make them go away, prompting the weary reply, "Yeah, I thought you might." Not someone we're likely to form an easy bond with, then.

The next day, Boyle and his boys are back in the pub and waiting to collect a payment from factory worker Malky (a very good Alex Norton), whose drinking habits have landed him in Boyle's debt but who has been pressured to hand over his wages to his neglected wife and child at the factory gate. When he reveals to his wife that the money is owed to Boyle, she coldly responds, "I'll not expect you home, then." His fearful approach to the pub on seeing Boyle's car outside, coupled with his reluctance to enter with his friends and his trip a nearby alley to vomit before folowing them tells an ominous story about his impending fate, and by association what happens to anyone who fails to make their repayments to this most unforgiving of moneylenders. As the fragile Malky approaches Boyle, the sense that we're watching a condemned man walk towards his executioner is overpowering.

Yet midway through his frightened plea for clemency, the news comes that a couple of hard lads from a rival gang are kicking off in the other bar. Boyle thus collects his second-in-command, tells Malky that his debt has consequentially increased but that he will give him a week's grace to come up with the cash, and walks next door to confront the troublemakers. And from the moment he verbally intervenes we're in his corner, as he is transformed from a ruthless exploiter into the guy who steps up to put the loudmouth bully in his place. He's a bad guy, sure, but he's our bad guy. This is emphasised when Boyle leads the agitators outside for a stand-off that sends two wised-up local kids scurrying, and his calm intimidation trumps their twitchy agitation. But it's here that the battle lines are drawn for future conflict.

The conflict in question arrives that very evening when Boyle and his men are ambushed by members of this same rival gang. The brutality of the street fight that ensues is brought home by the fact that it is fought not with fists or pistols but long-bladed kitchen knives, while its effect on the local populace is shockingly illustrated when it spills onto a crowded bus. The impact of the fight is heightened by its vicious desperation and the documentary manner in which it is filmed, a heart-pounding sequence whose ferocity and jarring realism puts it on a par with the furious street battle between the London and Birmingham crews in Alan Clarke's The Firm. It's following this, after being picked up by the police and spitting blood in the face of the booking sergeant, that Boyle takes his first beating from those in authority.

Yet for sheer, wincing viciousness, even this street fight is topped by a subsequent revenge attack on Boyle in which he's ambushed outside a pub, where he is beaten senseless with hammers and left for dead on a snow-covered street. Despite the serious injuries he suffers, he arranges for his cronies to carry him to a pub frequented by his attackers so that when they enter they will see him drinking with friends, blood running from his forehead and a smile on his face. It's an act of almost self-destructive defiance that will effectively define him from this moment on. And our bond with him continues to be an uneasy one, with scenes in which he jokes with his cronies or visits the mother on whom he dotes offset by one in which he turns up on the doorstep of a rival and slashes his face with a razor, then on returning to his car asks, "was that the right guy?" and carelessly cracks a joke about his driver's clothing.

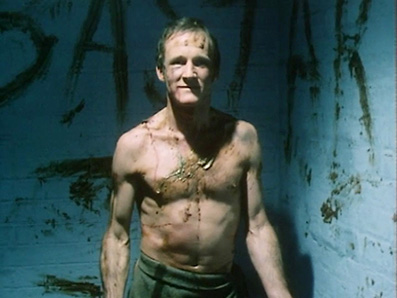

But it's once he's banged up in prison for life that Boyle's one-man war against the system really begins. It kicks off with an assault on the prison governor and a beating he takes from the warders in reprisal, which lands him, bruised and bloodied, in a padded cell, a defeat he turns into triumph by escaping his straightjacket and tearing the lining of the room to shreds. Boyle's nothing-to-lose stand against his captors and the grudge-driven violence dished out by prison warders effectively fuel each in a seemingly unbreakable tit-for-tat cycle of violence, one that looks set to end only with Boyle's eventual death, something one particularly vicious beating nearly brings about.

It's clear from an early stage that the system is ill-equipped to deal with someone like Boyle, a man for whom punitive repression and violence only seems to fire an almost instinctive need to aggressively kick back, irrespective of the consequences to himself and to others. All attempts to break him blow up in the faces of his would-be repressers, with even extended periods of solitary confinement – the soul-crushing isolation and monotony of which is very effectively captured here – fail to make a serious dent. Both sides of the conflict appear to justify their actions in part by collectively dehumanising the other, an attitude neatly exposed when Boyle is released from a nine month stretch in solitary and overhears a guard talking about his sister. Instead of jumping at the chance to take the piss, he stops dead and stares at him with a look of incredulity, which prompts this calm but tellingly delivered response:

"You never thought I'd have a sister or a family, did you, Boyle? We might be bastards to you, but we've got people and friends that don't think so. Who have you got, son? I've got a sister. I've got three sisters. You're the bastard."

It's small but crucial moments like this that prompt us to consider what it must by like to be charged with guarding someone like Boyle and to even attempt to get him and keep him on some sort of straight and narrow. That he should be the focus of the story is only right given that it was based on his autobiography, but while the film justifiably highlights his moments of triumph against an unhelpfully brutal system – his tunnelling through cell walls to unite with his comrades is a memorable highlight – it intermittently reminds us that there is a human cost to his aggressive non-compliance. It's a realisation that hit me hardest after a riot led by Boyle in response to an assault by guards on a fellow prisoner, when a bloodied and bedraggled guard pauses and says of the comrade he is helping to transport on a stretcher, "They've taken his eye out, sir." It's a small but significant moment that haunted me for years after I first saw the film.

One of the many real strengths of A Sense of Freedom is that it feels so authentic to its time and place, the result, no doubt, of being an STV (Scottish Television) production, adapted and directed by Scotsmen and featuring a home grown cast speaking authentically Glaswegian dialogue, at least in the original STV version (more on this below). The ace in the hole here is David Hayman, a brilliant but often underused Glaswegian actor who here delivers what could be the performance of his career as Boyle. Convincingly intimidating as an angry hard man but also effortlessly charismatic, it's he that keeps us fascinated by Boyle when by all rights we should want to turn our backs on him. Hayman doesn't play Boyle, he absolutely becomes him, every bit as much as Tim Roth became angry skinhead Trevor in Alan Clarke's Made in Britain. A strong supporting cast (including a no-nonsense turn from Fulton McKay as Boyle's police nemesis) ensures that even the smallest role registers, and all have been cast with the same care and attention to detail as the lead.

John Mackenzie directs with an arresting blend of thoughtful intelligence and gritty urgency, maximising the storytelling potential of camera placement and movements and time-compressing edits, keeping it real and never having to fall back on time and place captions or overly obvious expositional dialogue. Like the aforementioned Alan Clarke, he can tell small stories in a single dolly shot (Boyle's status is nicely illustrated by people he meets and interacts with during an edit-free walk through his community), and when the violence explodes, master cameraman Chris Menges (who also shot the Made in Britain for Alan Clarke, and Kes, The Gamekeeper and Looks and Smiles for Ken Loach) is in the midst of it like a war photographer with an artistic death wish, adding to the sense that what we're watching is real.

Although shot between the completion of The Long Good Friday and its delayed release (a big thank you to Michael Brooke for pointing this out), for me A Sense of Freedom is a tougher and grittier work and as a filmic crime drama every bit its justifiably acclaimed predecessor's equal, and deserves to be discussed in the very same breath as the abovementioned Clarke duo of Made in Britain and The Firm. A Sense of Freedom is the sort of superb, committed and risk-taking television I simply can't imagine being commissioned today, let alone made, and is thus to be treasured, appreciated, repeatedly watched, and enthusiastically shared with those who have yet to experience the thrill of seeing it.

From a modern perspective at least, there is a small sense of incompletion about the story told in A Sense of Freedom. This is hardly surprising, given that Boyle was still serving time when the film was made and that the transformative effect on his life of the Special Unit at Barlinnie is not covered here, only hinted at in the film's final sequence, the full meaning of which you are left to interpret. It's at Barlinnie that Boyle discovered a love and talent for sculpture and wrote the book on which this film was based. Following his parole in 1982, he moved to Edinburgh, and in 1983 founded the Gateway Exchange with his wife Sarah and artist Evlynn Smith, a charitable organisation set up to help ex-convicts and recovering drugs addicts through art therapy, a project that received support from the likes of Sean Connery, Billy Connolly and John Paul Getty. Boyle has since become an international sculptor of some note and in 1984 wrote a follow-up book to A Sense of Freedom entitled The Pain of Confinement: Prison Diaries, which was followed in 1999 by a novel, Hero of the Underworld.

There are two versions of A Sense of Freedom included in this set, the one originally broadcast on STV and the one prepared for UK cinema release under the Handmade Films banner. This will bring cheer to those who for some years now have been itching to get their hands on the original version with its Glaswegian dialogue, which was redubbed with a more generic Scottish dialect for the cinema release and in the process underwent a number of subtle but still unnecessary changes.

But even with that in mind there is a significant reason to favour the STV original over the cinema version, at least as it's presented here. Here's the problem, or should I say problems. The original was shot on 16mm in the 4:3 aspect ratio, which was the television standard of the day. To conform it to the ratio of 1.85:1 for the cinema version, the image was cropped at the top and bottom. Then for its transfer to DVD, that 1.85:1 ratio has been cropped at the sides to re-conform it to 4:3, something confirmed by the opening shots with their superimposed credits, which are presented in letterboxed 1.85:1. The cinema version is thus missing a sizeable portion of the picture information on all sides when compared to the STV original (see the comparative frame grabs below).

The original STV version (left) compared to the cinema version (right)

It should be noted that this is the exact same transfer that you'll find on the previous Anchor Bay DVD, which featured only the cropped cinema version. The cinema print also includes captions to identify dates and locations, something that was not included in the original, and the opening titles have been redesigned. Perhaps even more significantly, the cinema version is approximately 7 minutes shorter than the STV version, suggesting some cuts have been made. I've not had a chance to do a direct side-by-side comparison yet and have a deadline to hit.

Back in days of yore, 16mm TV material tended to look a little rough when originally screened, likely the due to a combination of the film-to-video transfer technology of the day and the dodgy TVs on which we tended to watch them. Maybe that was just me. The smaller frame size does mean that 16mm has a lower the resolution than 35mm and grain thus tends to be more prominent, particularly on the higher speed film stocks. But 16mm can still look damned good if carefully remastered – witness the results achieved on Network's Tales Out of School Blu-ray set. I'll wager that the STV looks even better on this DVD transfer than it did on its original TV screening (it's too long ago for me to clearly remember), and while not of the quality of Tales Out of School, the image is reasonably detailed and the contrast rather good, although solid black levels have sometimes been achieved at the expense of shadow detail – it's hard to make out much at all when Malky nips into a darkened alley to throw up before meeting Boyle. There's a dour look to the image that was very likely intended, and does tend to locate the film in a particular period of British TV. A few instances of dust and dirt are still very visible, but on the whole the print is surprisingly clean.

Being effectively a blow up from the 16mm original, the detail on the cinema version is very slightly softer, but the colour timing is also different, having more of a green hue to areas that leaned towards blue in the original. Which is more accurate I wouldn't like to say, but I personally preferred the STV print. The picture is also slightly lighter and the contrast a bit more forgiving in the shadows. More dust and dirt is visible on this version.

The Dolby 2.0 mono soundtrack on the STV version is clear enough without ever sparkling, and is outclassed somewhat by the louder and brighter soundtrack on the cinema version, which particularly benefits Rory Gallagher and Frankie Miller's bluesy, guitar-driven score. There's no serious damage evident on either track, though there is a detectable underlying hiss.

There are no subtitle options on either version.

Sarah's Story (25:56)

A 1986 STV documentary portrait of Sarah Trevelyan, a former psychiatrist who married Jimmy Boyle in 1980 and after his release co-founded the Gateway Exchange with him. She recalls meeting and falling for Boyle while he was still at Barlinnie and their later decision to marry, and the work of the Gateway Exchange is covered in some detail. There's press footage of the couple on their wedding day and film of the shaping of the Gateway and the work being carried out within its walls. Boyle himself is also interviewed about the purpose of the centre, as are a few of those who have benefitted from the opportunities it offers. A really useful and fascinating postscript to the film.

An excellent film in a largely worthwhile package. The inclusion of the original STV version in its original aspect ratio is the prize attraction, though the sole extra feature is also welcome, providing as it does a partial postscript to the story, though an update on the details of Boyle's art and literature career since would also have been welcome. The inclusion of the cinema version of the film certainly makes sense for those who do not have the Anchor Bay release, but the cropping of the picture ensures that I'll go with the STV version every time. For the film itself, the inclusion of an unmolested STV original and the extra features, this Odyssey release thus comes recommended.

|