|

More than once over the course of the past couple of years, it's struck me that this site's coverage of the cinema of Ken Loach has been a little anaemic, particularly given the high regard in which he is held by at least two of its contributors, one of them me. To date, we've only reviewed three of his films – The Wind That Shakes the Barley, The Spirit of '45 and Tickets, on which he shared directing duties with Abbas Kiarostami and Ermanno Olmi – and posted a single article on his work, though the Spirit of '45 review and Ken Loach – Politics and Cinema, both by Jerry Whyte, did include a detailed overview of his oeuvre. Then again, as our review schedule has become increasingly dictated by the titles that land on our doormat, our days of reviewing anything we fancied rather than what is coming up for release have become a fond but distant memory. Loach has continued making films, of course, but not being based even close to London, I tend to get to see them a few months after their initial release when we screen them at the film society I help to run, by when a film review would be just a weeny bit redundant. That said, if some enterprising independent distributor could snag the rights to Loach's early and mid-career work, fund full restorations and put them out as a series of well-featured Blu-rays, then I have a feeling Jerry and I would be on them in a flash. Which frankly is a ball that Eureka have started rolling with this welcome Blu-ray release of what remains Loach's most beloved film, Kes.

If you've never seen Kes then why the hell not? If you've never even heard of it then I can only assume that you're young, raised almost exclusively on Hollywood movies and have yet to start making your way back through the rich history of British cinema. There, how condescending was that? Either way, a quick plot summary would probably be in order. Working class, 15-year-old Billy Casper lives with his mother and bullying older half-brother Jud in a Yorkshire mining town. He struggles to concentrate in school, has a past history of petty criminal behaviour and his future prospects look bleak. When he steals a kestrel chick from a nest and starts to raise and train it, however, his previously directionless life begins to take on a strong sense of purpose.

Simple, huh? Well, in story terms it is. So what is it that makes Kes such a special film? Ah, where to start? Well, that's the problem. When you're talking about a film as universally acclaimed as Kes (how many other films can you name that have a 100% approval rating on Rotten Tomatoes?), especially one that was released 47 years ago that has been extensively written about by more learned others, whatever I say about the film, whatever observations I might sincerely make, I can pretty much guarantee that someone else has made them before me, and probably with a lot more eloquence than I could possibly muster. So as tends to be our way on this site, let's get personal.

I'll come clean here and freely admit that I didn't grow up in a Yorkshire mining town and although my parents were far from wealthy, we weren't exactly scrabbling for food or fuel. As kids, we did OK. But when I first sat down in front of Kes, I recognised so much of what Billy goes through from personal experience that I began to wonder if writer Barry Hines (whose co-written screenplay was based on his own exquisitely titled novel, A Kestrel for a Knave) and director Ken Loach had somehow found a way to raid my glummer childhood memories. What they'd tapped into, of course, was a collective experience, one that few if any TV or (especially) film dramas of the day were remotely interested in exploring or truthfully depicting on screen. For Billy, school has precious little to offer, to which those charged with educating him respond with verbal and physical bullying, public humiliation and disproportionate (and clearly ineffective) levels of punishment. Billy is a loner, as much an outsider in his own home as the schoolyard, a boy repeatedly castigated in class or even in school corridors, often not for anything he's actually done but just for being Billy Casper – so often have his teachers lost patience with him that they now appear to simply target him by default.

For younger viewers, this method of would-be social conditioning and control must come across as borderline barbaric or even play as a fanciful attempt to more readily show Billy in a sympathetic light. But those of us who were similarly targeted by both educators and fellow classmates alike can testify to the absolutely spot-on accuracy of its depiction here, from the verbal abuse and sharp clouts dished out for even the smallest infraction to the too-readily employed corporal punishment used by the school's angrily intolerant headmaster. I could and probably should go on a passionate rant here about the cruelty and ineffectiveness of corporal punishment as an archaic method of behavioural control, but it's a subject I've already concisely covered in my review of writer David Leland's Tales Out of School quartet of TV plays – if you're curious about my views on the subject then follow this link and check out the second paragraph of Birth of a Nation. I think that says it all.

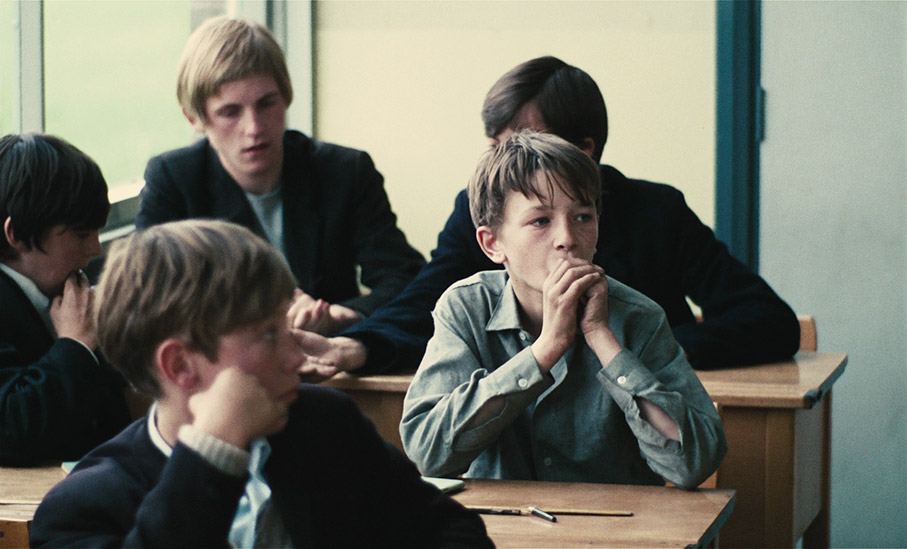

What really struck me on my first viewing of Kes, which was back before I even knew who Ken Loach was and thus before I became familiar with his singular style and approach, was the astonishing honesty and realism with which all this is portrayed. By casting the kids and their teachers primarily from the school in which the film was shot (and where writer Barry Hines was once a teacher himself) and having them draw on their own life experiences whilst adopting an almost invisibly observational approach, Loach and his collaborators brought the tone and feel of their drama so close to documentary that the line between these two seemingly contradictory film forms is blurred to the point where they repeatedly merge. This is perhaps most evident in the scene where Billy encourages his kestrel – the eponymous Kes – to make its first flight, a heart-lifting swoop from a fence post to his waiting glove that was only possible to stage and film because young first-time actor David Bradley learned to raise and train the bird in question, in essence playing Billy by becoming him. Thus when prompted to give a talk to his classmates on the process of training the bird, he's talking from experience, and it shows in his stumbled but still knowledgeable delivery and the honest reactions of his spellbound classmates.

It's this potent air of documentary realism, coupled with young Bradley's easy likeability as Billy and the empathic bond that any sympathetic audience should form with the character, that makes Kes such an involving and ultimately moving film experience. Yet Loach is still willing to play the odd game with this approach for the sake of entertainment. It's for good reason that the film's most fondly remembered sequence is the sports lesson football match, a scene that absolutely nails just about everything that those of us who detested having to play sport of any kind at school still shudder at the memory of: having to dress up in shorts and a t-shirt and go outside in winter, when the weather dictated we should be indoors in coats; being forced to wear ill-fitting spare kit when you had none of your own; the ritual weekly humiliation that came with being one of the last to be picked by the team captains (who always hated you anyway); the bullying sports master who regularly balled you out for you lack of enthusiasm and insisted on watching you undress and take a post-match shower (what was it with the damned showers?). Yet Loach kicks off this otherwise realistic sequence with sport programme intro music, and slap bang in the middle pokes a small but delightful hole in the fourth wall by posting up team scores as they would appear on a televised game, with goals attributed to the captains' chosen first division teams. That the sports master is played by an English teacher who moonlighted as a wrestler in the evenings named Brian Glover – who went on to have a very successful acting career and became one of TV and cinema's most instantly recognisable voices – adds a layer of star quality to his lively introduction that the makers surely can't have dreamed it would later acquire.

There's a poetry to Kes that comes in part from the young age of its protagonist, fuelled as it is by childhood memories rather than the adult fears an angry sense of injustice that drive so many of Loach's later works. The social politics are certainly less overt here than the likes of Riff-Raff, Ladybird Ladybird or My Name is Joe, all excellent films that confront contemporary social injustice through involving and deeply affecting personal stories of adult hardship and suffering. But while the social commentary in Kes is more subtly handled, it still comes through clearly and really stays with you, particularly given the emotionally punishing turn the story takes in its later stages. That Billy fails to respond to the bullying and production line teaching to which he is subjected seems hardly surprising from a modern perspective, where inclusivity and differentiation are now watchwords in classrooms where every student is expected to be given equal opportunity to succeed – whether this happens in practice is a subject for further debate, of course, and is likely to be inflamed by this government's determination to return to a school system that consigned kids like Billy to the social scrap heap in the first place. For him, Kes represents a sense of hope and purpose that school and even family have failed to provide. It has the potential to be the making of him, prompting him as it does to make his first visit to the local library and to study his first book (his decision to steal it may seem like a hangover from a troubled past that is only hinted at here, but is effectively forced on him by circumstance), and to dedicate himself to something that potentially could have a transformative effect on his life, much as it did on writer Barry Hines' brother Richard, on whom Billy appears to have been largely based.

Like Billy, I had my share of brushes with juvenile criminality and gained no sense of purpose or direction from my schooldays, and like him developed a thirst for learning not though what I was force fed but what I discovered as a result of curiosity and solitary interests, and would have welcomed the sort of quiet encouragement offered to Billy by the film's only sympathetic teacher, Mr. Farthing (played by Colin Welland, one of the very few professional actors on board here). That connection with my educators came later in the sort of further education colleges that successive governments have starved of funding and the current one – made up as it is of privately educated multi-millionaires – seems depressingly determined to drive into the ground.

Returning to Kes after a break of several years brought back many memories from my own intermittently troubled childhood, some of which the distance of time have rendered more colourful than they probably were at the time. I was struck once again by the film's truthfulness and sensitivity, but also by the way Loach uses humour to both entertain and reinforce a socio-political point, as in the scene in which a shy kid is sent to deliver a message to the headmaster and ends up being caned with his classmates by an authority figure who is on too much of a punitive rant to listen to what this poor boy is trying to tell him. The moment when this bluster has all of the boys secretly giggling behind his back – including the one who is being wrongly punished – triggered probably the strongest memories of all and still puts the widest of smiles on my face.

We're currently at a worrying crossroads in British cinema, where one of our greatest and most politically committed filmmakers may well have just made his final film (one that everyone should see and use as a basis for political protest – it's only going to get worse over the next few years, people), and I can't help but wonder if someone else is ever going to step up to the plate to pick up where he leaves off. In my humble view, no-one ever made films like Ken Loach, and even today at the ripe young age of 80 he's still number one in a field of one. Yet at a time in which the poor are being punished, demonised and used as scapegoats for the failings of neo-liberalism by politicians, the right-wing press and the sort of gullible, self-centred and easily-led idiots whose numbers depressingly seem to be on the rise, we absolutely need people of Loach's commitment, humanity, and skill as a filmmaker and passionate campaigner for society's underdogs. That a film as exquisitely devised and executed as Kes was only his second feature and that it almost never got made because almost no-one saw any commercial potential in the story now beggars belief. Then again, perhaps I'm answering my own implied question here, and the reason that Loach appears to have no direct successor is that there's no-one out there prepared to fund or distribute or even screen their work. If Loach does now retire from filmmaking – which he planned to do before, until his anger at the terrible impact government policy was having on the most vulnerable members of society gave birth to the searing I, Daniel Blake – we can still be thankful for the extraordinary body of work he has delivered over the years. And if you're somehow new to it, I can't think of a more perfect introduction than Kes.

If there's one word I've tended to associate with the look of Kes over the years, it's that old favourite, ‘gritty'. Mind you, it's a word commonly associated with British social-realist dramas of years past, and there are two good but slightly unfair reasons for this. The first is that the filmmakers in question have favoured realism over artificiality and tended to light and dress scenes accordingly and shot on high speed (and higher grain) film stock. The second is that we've been watching these films for some years on TV and even DVD on sub-standard transfers from iffy quality prints, the same prints, I'm guessing, that were sent to independent cinemas for just about all of the screenings of such films that I've attended. And so it was with Kes, at least until now. The special features confirm that the film's interior scenes were lit through a combination of lights shone through windows to emulate daylight and indoor light fittings, and that the film was shot on 100 ASA (now ISO) film stock, the fastest available to filmmakers shooting colour at the time. The difference with the transfer on the Blu-ray in the new dual format release is that we're not looking at a grubby TV transfer from a washed-out and damaged print, but a new 1080p, 1.66:1 restoration, and while the documentary feel of the lighting and photography remains unchanged, the image itself has been completely transformed. Most immediately evident is the considerably increased sharpness and level of detail, and while this may not be obvious in some shots (the opening image of Billy in bed with the curtains closed gives you no idea), you're frequently left in absolutely no doubt that Kes was shot on 35mm film. The naturalistic lighting does cast a (realistic) gloom over house and shop interiors, and the punchy contrast and beefy black levels cast some detail-swallowing shadows, but this always feels right for the film's chosen aesthetic. The colours of clothing and sets are deliberately and appropriately drab, but really pop when required – the green of the fields in which Billy trains Kes is seductively lush, and the spines of some of the books in the bookshop in which he acquires his training manual are almost luminous. The film grain is finer than I ever remember, though does coarsen occasionally, suggesting the film speed was pushed (exposed at a higher speed with adjustments made to the development to compensate) on some shots to work in lower light. All in all, a terrific transfer.

The linear PCM 2.0 mono soundtrack is also in good shape, though the location sound recording is not quite as crisp as you would find on a mainstream movie of the period. It's always clear, however. John Cameron's evocative score is cleanly reproduced, and there's no background hiss or damage to contend with.

Also included here is an alternative soundtrack, for which some of the actors were asked to re-record their lines to ‘soften' the Barnsley dialect, a process that neither Ken Loach nor producer Tony Garnett were involved in. According to Loach on one of the extra features here, this only affects the first two or three scenes, and while you can certainly detect the difference in audio quality – ADR (additional dialogue recording) is recorded in a studio and not on location, so lacks the ambience and acoustic quality of the original – my ear for accents is perhaps not fine tuned enough for me to start picking apart the specific differences between the two. Then again, I never had any problem understanding the dialogue as it was originally spoken – I grew up exposed to such a wide range of accents and dialects that I've yet to encounter one that completely stumps me (I've struggled occasionally with a couple, which I'll tactfully not name, but have generally got by). If you were born and bred in Barnsley then I'm sure this will have you howling with disbelief – I'll stick with the original soundtrack every time, which the film rightfully defaults to this when you play it.

You can also watch the film with an isolated music and effects track, should you so wish. I've still never sat through an entire film this way and have yet to find any reason to do so, but it's there if you want it.

Optional subtitles for the deaf and hearing impaired (and those who struggle with accents) are also available.

The first 7 extras here are located under the heading Interviews.

David Bradley – Actor (20:15)

A welcome chat with David Bradley, who played young Billy Casper in the film, in which he recalls auditioning for the role (along with about 70 others), his busy working schedule during the shoot, learning to train the kestrel, filming (and being paid extra for) the caning scene, being asked not to read A Kestrel for a Knave to avoid knowing the end in advance of its filming (only to have it revealed anyway by his classmates), and plenty more. He also revisits a couple of the locations, and it's a testament to the impact the film still has in the town in which it was shot that the fish and chip shop that features briefly in it is now called ‘Caspers'. Although technically a tad uneven (the sun comes out and overexposes the image a couple of times, and the sound jumps a little in volume on one segment), the content is enthralling.

Tony Garnett – Producer (26:22)

Loach's once regular collaborator, producer (and later director) Tony Garnet, recalls how he and Loach first met and began working together, how their desire to break the mould of TV drama ran up against a wall of traditionalism, the influence on both men of contemporary Czech and Polish cinema, discovering the work of Barry Hines and trying to persuade him to write for The Wednesday Play, the stop-start process of getting the film under way (this is fascinating – I really had no idea that the film came that close to never being made), the initial reaction to it and so much more. An essential extra.

Richard Hines – Kestrel Advisor (31:29)

If that surname looks familiar, then that's because Richard is the brother of A Kestrel for a Knave writer Barry Hines and the person on whom Billy Casper is largely based. There were clearly strong similarities between Billy and the young Hines, who also took a kestrel chick from its nest and learned how to raise and train it from a book at the local library, and both were initially cast as secondary modern school write-offs. He gets quickly onto being offered the job as falconer on the film and goes into considerable detail about the experience of making it, which includes his admiration for David Bradley's commitment to his role (he worked all day on the film, trained with the kestrel early evening and then went home to learn his lines for the following day), and a couple of telling anecdotes about Loach's directing technique. He also talks about his own career as a filmmaker and his determination to make films that stood up for working class people, and confirms that his obsession with falconry gave him a veracious appetite for learning and changed his life direction. He also says tellingly of hawks that "they don't understand social subservience; they cannot be bullied or threatened."

Chris Menges – Director of Photography (8:07)

One of this country's most gifted cinematographers (take a look at his filmography on IMDb if you're in any doubt) looks back at his first feature film as director of photography that was the beginning of a multi-film collaboration with Loach. He usefully outlines some of the technical aspects of his approach, which included lighting sets through windows or with interior practicals (lights that are visibly part of the scene) and shooting from a distance with longer lenses to give the actors full freedom of movement. He also reveals that both he and Loach were heavily influenced by Milos Forman's A Blonde in Love, and he was thus bowled over when he had the chance to work with and learn from that film's cinematographer Miroslav Ondrícek on Lindsay Anderson's If....

Bernard Atha – Actor (11:21)

Actor Bernard Atha, who plays the youth employment officer in Kes and later worked with Loach on Family Life, 1916: Joining Up and The Rank and File, recalls how hard he found it to see Loach as a director on their first pub meeting, his subsequent work and friendship with him, and unexpectedly nailing his scene on the first take. Although he believes he benefitted from his parents buying his way into grammar school, he champions the comprehensive schools that replaced them as superior, and as someone who became addicted to the arts, he remains convinced that exposure to great art in all its forms could be beneficial to all, which he illustrates with a rather nice story from his teaching days.

Penny Eyles – Continuity (5:27)

Penny Eyles – whose role on Kes is one that few outside the world of filmmaking probably understand the importance of – talks a little about the specifics of her work on the film and why it was sometimes prudent not to be too strict when the continuity was broken. She also reveals that Loach would often start scenes before the camera was rolling to give the actors a lead-in and quietly give the nod to the camera operator to start filming, which aided his naturalistic approach. One of the shots here is a little soft on Eyles' face, but again, it's all about the content.

John Cameron – Composer (8:41)

Immensely likeable composer John Cameron reveals how he unexpectedly landed the job of scoring his first film (this is a good one), says of his approach that "the film was so real I couldn't write anything was not real" and that he couldn't falsify an emotion because there was nothing in the film that needed a musical push to register. He plays some of the music used on the soundtrack, provides some technical details of the timing of the main theme, and neatly sums up the film's unique qualities when he says that it doesn't exist in genre, and that "Kes is Kes."

1992 Ken Loach Guardian Lecture (70:19)

A recording of a Guardian interview conducted with Loach and the National Film Theatre (now BFI Southbank) by critic Derek Malcolm (who also chaired the interview with Loach that I attended a few years later). It kicks off with a discussion on Kes, but there's a lot of ground covered here, and when Malcolm has finished he invites questions from the audience, all of which Loach answers with honesty and good humour. What really comes across here is how entertaining a raconteur Loach can be, as does the purity of his political commitment and his dedication to the filmmaking art. Being a then recent film – one that kicked up a bit of a political storm in the UK – there are a lot of questions about Hidden Agenda, and Loach tellingly remarks at one point that there appears to be no confidence in British films or our own culture because it's being driven out by the free market.

2006 Reunion Panel (57:26)

A reunion panel discussion arranged for a screening of Kes at the Bradford Film Festival on 9 March 2006, chaired by Anthony Hayward and consisting of director Ken Loach, producer Tony Garnett, writer Barry Hines, actor Colin Welland and Life After Kes author Simon Golding. As you would expect, this is more specifically focussed on Kes and its production than the Guardian interview, and while there is some overlap with the individual interviews above, there are still a good many stories unique to this feature. Loach talks about setting and shooting films in Yorkshire and what he would like to have changed about the final scenes; Colin Welland recalls the scene that he holds most dear and how it was filmed; Tony Garnett reveals that the two films turned down by Rank for distribution in 1969 were Kes and Ken Russell's Women in Love, two of the most respected and successful British films of their day; Barry Hines is asked to speculate on what sort of life Billy would be leading now; and a question from the audience brings up the issue of the redubbed soundtrack, which is included on this disc. It's all shot wide and from a distance, and the sound clarity depends on how closely the interviewees hold the mic to their faces.

Theatrical Trailer (2:56)

An interestingly toned trailer that suggests there's something wrong with Billy and that whatever it is, it's a secret he only shares with Kes. If I'm not mistaken, that's actor Patrick Allen delivering the sober voice-over.

Booklet

Heading up the content here is a solid essay by Philip Kemp titled Championing the Underdog – Ken Loach Before and After Kes, which is followed by a collection of archival imagery, including posters, lobby cards and production stills, something usually found as an on-disc extra. Credits for the film and the usual notes on viewing have also been included.

A still marvellous film given the sort of treatment it's for so long been crying out for – the transfer is terrific, the extra features (which collectively run for just over four hours) are all superb and there are even a couple of soundtrack options, making this as close to a definitive home entertainment release of the film as you're likely to see. Masters of Cinema deliver once again. Very highly recommended.

|