"Golden rule number one. The only rule. Get through the day. And that's all." |

Deputy Head Vic Griffiths' world-weary

advice to idealistic newcomer Geoff Figg |

In these days of generic, play-it-safe television drama, it's easy to be nostalgic for a time when such work could, for all the right reasons, be controversial, ground-breaking and exciting viewing. This was a time when writers were given the freedom to stretch their creative muscles and often responded with scripts that would attract the cream of emerging and established talent, both in front of and behind the camera. A leading light of the early 80s was David Leland, an actor who took up screenwriting and later direction, both to considerable and award-winning acclaim.

His television writing career began with two entries into the BBC's widely respected Play for Today series, Beloved Enemy and Psy-Warriors, both of which were directed by the great Alan Clarke. But it was his quartet of TV plays made under the umbrella title of Tales Out of School that really put Leland on the map. The most widely seen and celebrated of these marked his third and most fruitful collaboration with Clarke. I'll get to that later.

The driving force behind the project was Margaret Matheson, an adventurous producer who had first worked with Clarke on the TV version of Scum, which had suffered a BBC ban before its scheduled screening. She had also produced a handful of the most celebrated entries in the Play for Today series, including Who's Who and Abigail's Party for Mike Leigh, and Licking Hitler for her then husband David Hare. By 1982 she had moved from the BBC to become controller of drama at Central Television, where she was actively encouraged by director of programmes, Charles Denton, to take chances with writers and material. She had not been in her new position long before she was approached by Leland and Clarke with an idea for a film about the politics of famine, which for some reason failed to excite her interest. What she really wanted to do was something about education, and Leland was given free rein to research the subject and shape the results however he saw fit.

Taking the 1944 Education Reform Act as his kicking off point, Leland explored a number of educational issues from the viewpoint those working and learning within the system, those excluded from it, and families who had made decision to educate their children at home. The result was four feature-length television plays, each exploring a different aspect of modern secondary education, and each an example of socio-political television drama at its thought-provoking and compelling best. And while they are in some respects documents of their time and place, many of their observations are as sadly relevant today as they were when they were first broadcast.

There are sequences early on in the suggestively titled Birth of a Nation that feel almost as if they were lifted from a slice-of-life documentary about an average day at a British comprehensive school circa 1982, as students arrive on the first day of a new term and the film flits between classes and academic offices, briefly pausing to observe the activity unfolding there before moving on to the next. Gradually scenes lengthen and characters are established, and what starts as an observational documentary develops seamlessly into a study of an outmoded educational model that has refused to adapt to changing times, a battleground in which the struggling educators are driven by a singular purpose, to drum the set syllabus and the importance of qualifications into their students, irrespective of their interest or desire to learn.

For those younger readers still fresh from their school years, there are elements here that will feel genuinely alien, notably the use of corporal punishment as a method of behaviour control, which was outlawed in state schools in 1987. It's something Leland admits to being passionately opposed to but that still has its staunch supporters today, who blame its abolition for what they believe is a steady decline in classroom behaviour. I'm not a psychologist or even a parent, but I did experience this particular approach to school law and disorder in my junior school years, where I was whacked and hit by teachers on enough occasions to plainly demonstrate its ineffectiveness as a deterrent. It was only years later, with the advantage of hindsight, that I realised these assaults were never qualified beyond the assurance that I'd suffer similar punishment should I misbehave again. No-one ever tried to explain the consequences of my misbehaviour or explore the reasons for my deviation from their perception of the straight and narrow. As a corrective measure, corporal punishment was next to useless. It hurt for a while and was briefly humiliating, but having taken my beating I would wear it like a badge of honour – the more times you were hit, the harder you were perceived to be by your impressionable peers. And far from teaching this wayward student respect, it taught me resentment and that an effective way to exercise power was through physical violence. If you got hit enough times, you learned to pass it on. Which led to you getting hit again. And so on.

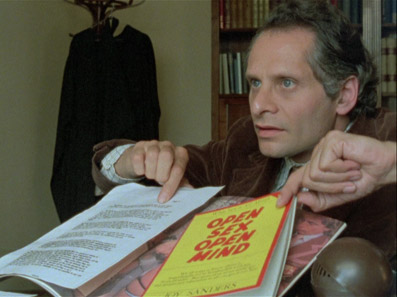

In Birth of a Nation, it's a punishment dished out for almost any violation of classroom protocol and selected for its expedience by teachers too busy to deal with the infraction in constructive depth. Given the choice, pupils always report to deputy head Vic Griffiths (Robert Stephens on excellent form), who gently cajoles even the most reluctant victim into accepting a casual whack in preference to the time-consuming process of contacting their parents. It's a different story with gym teacher Barratt (Bruce Payne), an authoritative bully whose fearsome approach to teaching involves loudly berating his students and hitting them for even the slightest transgression. Other teachers are not as physically violent but are still verbally aggressive, barking commands and information at pupils and attempting to frighten them with the consequences of academic failure, a symbol of which is the gang of ex-students who hang around the school gates and cheerfully hurl abuse at the staff caged within.

The one ball of academic discontent is science teacher Tom Twentyman (a quietly excellent Bruce Myers), who communicates with his students, refuses to grade their work, and teaches what he believes they need to know rather than what has been prescribed by headmaster Mr. Griff (Richard Butler). And relatively new to this educational maelstrom is Geoff Figg (a young and commanding Jim Broadbent), a determined progressive who disregards the established educational approach, leads discussions on taboo subjects, and leaks information about the school's level of corporal punishment to the local press.

Instantly and continually compelling as drama (you can drop in at any point and become hooked in a few seconds on the basis of the dialogue and performances alone), the film also shines as a thoughtful critique of an inflexible and outmoded educational system straining at the seams. It even delivers as a social parable, casting Twentyman as a dissident working within the system (his lecture to outraged traditionalist Griff on the sexual implications of being a "spanking school" is an absolute hoot), Figg as a would-be revolutionary and the former student gate-hangers as a disaffected proletariat, who, in a final and perhaps inevitable act of revolution (triggered by a spur-of-the-moment window smash that can't help but foreshadow Spike Lee's own famous call to anarchy in Do the Right Thing), attack the school, overturn and burn cars, and prompt authority figures to run for their lives and barricade themselves in a prison of their own making. Utterly superb television.

Leland was already familiar with a real-life case of a family who had chosen to educate their children at home when the Tales Out of School project was first suggested. Further research led him to a group known as 'Education Otherwise', and through them he met the family on which Flying into the Wind was based. Leland's story mirrors theirs, both in their approach to their children's education and the attempts by the authorities to force them to return their youngest child to school.

An initial motivation for the switch to home education is provided early on by young daughter Laura's glum classroom isolation and her genuinely distressing trauma (communicated with heartbreaking authenticity by Prudence Oliver) at the very prospect of returning to school. The film then jumps forward eleven years, by when her family have moved to a farm in the country, Laura has left school and is working as a plumber, and mother Sally (Rynagh O'Grady) is in court for the umpteenth time to justify her decision to educate the now 11-year-old Michael (Adrian Wagstaff) outside of the school system. The court case itself is cross-cut with footage of Michael at work on his parents' farm, helping his father Barry (Derrick O'Connor) to build a boat, listening to the life story of a passing tramp (Alex McCrindle), and questioning a doctor (Christopher Hancock) when the police turn up to recover a body found drowned in a nearby lake. This location switching allows the film to neatly undermine the court's assertion that Michael is missing out on his education by showing him fully engaged in a learning process that is based on practical application and triggered by his own curiosity.

It's here that both Leland and the real-life families on whom his screenplay is based were clearly ahead of the educational game. Despite his inability to read and write, something his mother believes he will learn when the need arises, Michael has effectively embarked on an on-the-job training programme with real-world applications and achievable goals, elements that have become crucial to modern vocational courses. This is particularly well illustrated in his discussion with the doctor, where his questions reveal facts that even his father was unaware of, while his refusal to leave when the body is recovered is triggered not by boyhood morbidity but a genuine curiosity about what has occurred. He is a living testament to his mother's courtroom claim that "We have not taught our children, we've enabled them to teach themselves."

It's when the courtroom judge (the ever-wonderful Graham Crowden) decides to pay Michael a visit and witness for himself the effectiveness of the boy's self-education that the film really kicks against expectations. In a mainstream movie this would doubtless be the point where the sceptical authority figure would see at first hand the error of his assumptions, strike a friendship with the boy, and return enlightened to the courtroom to dismiss the case. But it doesn't play like that here. Despite Michael's matter-of-fact likeability and his practical skills, problems arise from the moment the judge arrives, which climax in a boat trip that ends in the pair having to wade ashore and make their way back to the farm on foot. The judge's frustration is further fuelled by Michael's consistently calm assurance that everything is fine, even when the boat they are sitting in is sinking. In a telling moment that could almost be referencing how things might have gone in a mainstream take on the story, Michael asks a weary judge as he sits in a warm bath, "Are you my friend?" Well he is and he isn't, as while ultimately sympathetic to Sally and Barry's devotion to their children, he still elects to uphold the rule of law, one that takes a more prescriptive and restrictive approach to educating children. In a beautifully executed but sobering final crane shot, we are left in little doubt that regular schooling, having previously failed to work for Laura, now looks set to do the very same for Michael.

Despite having worked in education myself for a number of years, RHINO is an acronym that I wasn't previously aware of. And I've heard a few in my time, my personal favourite being FOFO, which for those new to the term refers to projects that students are expected to research themselves and stands for "Fuck Off and Find Out."* RHINO is, or at least was in the 80s, a term applied to pupils who continually bunked off from school, and stands for "Really Here In Name Only." Pretty much every school I knew of had at least one such student and usually more, and their absence helped to keep a small army of Educational Welfare Officers in full time employment.

The RHINO in question here is the despondent Angie (Deltha McLeod), who ambles into to school wearing an expression and body language that speak volumes about her disaffection with her schooling, then departs mid-morning to shop for her family and collect her older brother's young son Charly (Andrew Partridge) from his playgroup. She's not long been home when she's visited by Educational Welfare Officer Brian (Derek Fuke), and it's here that some details of her situation emerge. Angie is a bright girl with a liking for mathematics (first hinted at when we see her mentally calculating the affordability of her shopping) but whose family responsibilities have seen her lose interest in lessons that have no practical application to her current situation. She's already been busted eight times for truancy and is on her fourth social worker, and is no longer receptive to anything that the well-meaning Brian has to say.

In a pivotal scene, Brian meets with Angie's head-of-year Alan Bartlett (James Warrior), her social worker Joyce (Victoria Burton) and Social Services officer Barry Clarke (Paul McDowell) to discuss the options for Angie's future wellbeing, options that include taking her into care and shipping her off to a boarding school in Norwich. With the exception of Alan, who believes her racial background is part of the problem and who leaves the meeting early to concentrate on his more academically successful students, they appear to be acting with the best of intentions. But what's crucially missing from this meeting to decide Angie's immediate future is Angie herself, who at that very moment is shown to be fulfilling Alan's cynical prediction and being arrested for shoplifting. The fact that she is doing so in order to give Charly a decent meal is never taken on board.

From here on in Angie becomes part of a system that is unsympathetic to her desire to be reunited with Charly and be left alone to look after her family, a need that drives her to escape from the care home in which she is placed and return to the very location that the authorities will look first. It's a spiral that leads all to quickly to incarceration, and a sobering final sequence of institutional humiliation in which a Angie is ordered to strip off and bathe under stern and unwavering gaze of her new custodians. Standing naked in the bath, she turns to the two women – and the audience who watch with them – and says with quiet bitterness and biting understatement, "It's not right, you know. It's not right."

There are precious few, if any made-for-television films that explode onto the screen with the attention-grabbing aggression of the fourth and most widely seen of Leland's Tales Out of School films. And I'm not talking on-screen physical violence, but the manner in which the film itself kicks off, in the ferocity of the music, in the face of the leading man, and in the locked-on-character steadicam that leads him from a waiting area to the courtroom in which the details of his latest offence are to be heard. This is Made in Britain, and it's one of the finest films ever to emerge from a television company anywhere.

The final and most fruitful collaboration between writer Leland and director Alan Clarke, it also introduced us to a searing new talent in the shape of Tim Roth, a young man who was clearly born to act but who famously only attended the audition by chance. It's the only film in the Tales Out of School quartet that has been previously been made available on DVD, as stand-alone discs by both Carlton and ITV, and as part of the superb Alan Clarke Collection from American distributor Blue Underground. It's been a favourite of mine since I was first sideswiped by it back in the early 80s, and my admiration of its many virtues has not diminished one iota since I first reviewed it back in 2004. Thus to avoid repeating myself, I would direct you to my original review for a summary of just why I still hold the film in such high regard.

As the climactic shout in the Tales Out of School series it can be seen as a natural progression from RHINO, one where the child at its centre – the articulate but ferociously aggressive Trevor – takes a confrontational approach to any attempt to control his behaviour and shape his future. But Trevor himself can envisage no future beyond what he can steal or demand from the here and now, and in this respect he is the series' most complex and difficult character, a victim who is also himself a victimiser, a self-centred aggressor who is seemingly unaware that the system he kicks against has the power to turn on him in ways he is as-yet ill equipped to cope with.

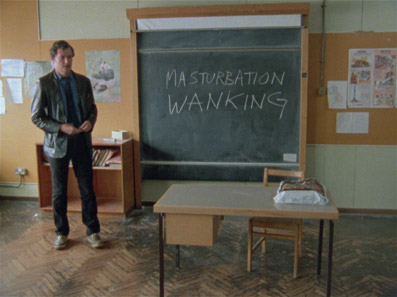

A common thread running through all four plays is the inability or unwillingness of both sides – particularly those in positions of authority – to talk to each other on equal terms. Problems and needs are acknowledged but not understood, in part due to a system whose channels of communication are rigidly defined and largely inflexible, and whose operatives are overworked and under-resourced. Only when those constraints are bypassed or ignored, as when Geoff Figg throws out the syllabus to initiate a frank class discussion on masturbation, does real dialogue between the students and their educators begin. It's significant that this scene occurs in Birth of a Nation, the first of the four films (at least by the running order on the discs – I've been unable to confirm their original transmission order), for as the series progresses such attempts to establish a level playing field dissolve into conflict and system-imposed rhetoric, where words are exchanged but little is actually taken on board.

In the extra features, Leland reveals not only that almost everything in the four films, including its key characters, was inspired by painstakingly researched fact, and that even the toughest elements, the ones you would think sprang from the writer's imagination, had a real-life equivalents that were even more extreme. He openly admits that "being a schoolteacher is an extraordinarily tough and difficult job," and set out from the start not to make a polemic but present an even-handed view (with the exception of his opposition to capital punishment, where all bets were off) of a system that was clearly failing a significant number of those it was designed to benefit.

But for all its continued relevance and its importance as a document of its time and place, it's in the series' strength as drama – the perceptive honesty of Leland's writing, the unwaveringly strong performances, the consistently excellent handling – that its true longevity lies. By having each of the four films explore a separate educational issue and place them under the control of different and very talented directors – Mike Newell, Edward Bennett, Jane Howell and Alan Clarke – each develops its own specific identity but remains organically connected to its companions, linked by Leland's thematic consistency and the dovetailing and development of issues from one film to the next.

Much has changed in the intervening years, of course, and communicating with students on a more meaningful level has become a recognised and celebrated educational ideal. But courses are still slaves to a rigidly prescribed syllabi and a disproportionate emphasis is still placed on academic achievement (just witness the press brouhaha that surrounds the publication of each year's A-level results). Perhaps most depressingly (and I'm speaking from personal experience here), the failure to effectively communicate has in many cases spread to the faculty itself which, now top-heavy with management, strangled by bureaucracy and groaning under the weight of short-sighted funding cuts, is driving away the very people whose talent and vision helped move education into the modern age.

As a quartet of television plays, Tales Out of School is on all fronts an extraordinary achievement. All four films are gripping, rewarding and still socially relevant viewing, but also function as finely tuned components of a complex, multi-faceted and beautifully executed whole. It's the kind of writer-driven and issue-driven approach to drama that springs from a creative freedom and willingness to take risks that, as Margaret Matheson observes in the extra features, has all but vanished from British television.

There's something about knowing that a film was shot for television in the 70s or early 80s on high speed 16mm stock that can't help but prompt lower expectations for DVD or Blu-ray picture quality. There are good reasons for this, as while this prejudice springs largely from memories of poor quality tele-cine transfers viewed on a dodgy TVs that pale in comparison to current plasma and LED screens, I've also worked with the film stocks in question, and shooting in low light usually meant sacrificing a degree of colour fidelity and picture sharpness, and tolerating a significantly more visible film grain. It's for this reason that I tend to cut DVD transfers of such material a degree of slack, as even the most careful restoration cannot remove film grain or restore picture detail where there was previously none. I was thus particularly intrigued by Network's decision to release Tales Out of School, all four of which were shot on high speed 16mm, on high definition. Would the image quality of these films justify that decision?

First and foremost, these are four separate films shot by three cinematographers under varying lighting conditions and quite possibly using different film stocks, and they may well also have been subject to different levels of preservation and storage. There is thus some variance in the quality of the image throughout the four films, with Flying Into the Wind the most visibly grainy and probably the softest on picture detail. Contrast here varies somewhat depending on the lighting conditions, being fine for the most part but intermittently softer in the darker scenes. Some variance in contrast can also be found on RHINO, but the grain is less invasive and the picture detail here is generally very good. The same is true of Birth of a Nation and Made in Britain, both of which really shine when the light levels are favourable – comparing the latter to its previous DVD incarnations shows a marked improvement in picture sharpness and contrast balance. All four films have been impressively cleaned up – there's hardly a dust spot to be seen, the colours are consistent, and the overall image quality is probably as good as any of the films have looked outside of Central Television's preview theatre. Given the limitations of the source material, this is an excellent job all round. And yes, the crispness of detail on best material really does justify the Blu-ray release.

In line with the picture restoration the PCM Linear 2.0 mono has been cleaned up and is free of noise or distortion, and the dynamic range is very respectable for a TV film made in 1982.

There are no English subtitles for the hearing impaired, which for some may well be a deal-breaker.

Twice Told Tales (28:58)

David Leland, with brief assistance from Margaret Matheson, recalls how Tales Out of School first came about and the real-life stories from which the plays and their characters were drawn. The details of his research are not only interesting, they also enhance your appreciation of the films as thoughtful and honest reflections of issues that continue to affect young people and educators to this day. Leland affirms his opposition to corporal punishment, and debates the issue with a group of current students at the end of a screening of Birth of a Nation. He concludes by pondering on how little has changed since the films were made, and reaffirms his belief that "being a teacher is an incredibly difficult and important job and they should be paid properly for doing it." A hugely informative and fascinating extra.

Digging for Britain (29:45)

Very much in the same vein as the above documentary (it was made by the same company, White Dolphin Films), there is initially some crossover in the story of how Tales Out of School first came about, but the specific focus here is Made in Britain, and using interviews with Leland, Margaret Matheson, writer and director David Hare and actors Sean Chapman and Eric Richard (who play Barry Giller and Harry Parker in the film), Digging for Britain tells the story of the film's inception, execution and intentions in often enthralling detail. The fact that Tim Roth was almost exactly how Leland had imagined Trevor is nice to hear, but its Margaret Matheson who leaves the strongest impression, bemoaning the current lack of creative freedom in television, reassuring a concerned Leland that "It's your job to write it and my job to get it on," and mischievously telling him as they embarked on the project, "Let's go out and make a bit of trouble." There's even a breakdown of the original ending and why it was cut, plus a post-credit reproduction of the screenplay for that scene, which strengthens the parallels with A Clockwork Orange. Another first-class extra feature.

Image gallery

A rolling gallery of production stills for all four films including images from the cut final scene of Made in Britain.

Also included with the release disc will be a 36-Page Booklet by Alan Clarke biographer David Rolinson, but this was not included with the review discs.

The absence of the Tim Roth commentary on Made in Britain from the Blue Underground set is a shame (and very likely a rights issue over which Network have no control), as is the absence of HoH subtitles, but these are the only gripes I have with this otherwise exemplary Blu-ray release from Network, which boasts four of the finest television plays of the past thirty years, digitally remastered and backed up by two substantial and information-packed extras. There really is nothing like this on British television today, and this is exactly the sort of thing that distributors should be resurrecting and preserving for future generations. This is a no-brainer – get it on Blu-ray or get it on DVD, the choice is yours, but whatever you do, get it. Bloody marvellous.

* In less cynical days it stood for "Find Out For Oneself."

|