| "Right

Banks, you bastard! I'm the daddy now! Next time I'll

fucking kill you!" |

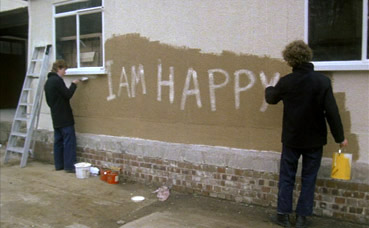

| Carlin snatches control from the resident daddy Banks |

As

1979 began, I was in my second year of film school. There were something like eight cinema screens in

the immediate area which I made a point of visiting at least three

times a week. The local arts centre was where you went

to see the older classics or the more recent foreign

language releases, while the mainstream and more successful

independent American releases could be caught at one

of three very large screens within walking distance

of the college. Many of these films were decent if unremarkable,

but just occasionally were extraordinary enough to convince

you that attending the first week of its release made

you part of cinema history (Alien, Halloween).

What rarely played in either location were British movies, and those that did tended to focus on the aristocracy.

This was the one thing I felt was missing from my regular

trips to the cinema, films that reflected my own life,

had characters that spoke as I did, that took place in believable settings

and had stories that were drawn from real life. Where were

the British realist films that had seemed so crucial

during the sixties, from Jack Clayton's Room

at the Top (1959) through to Ken Loach's seminal Kes (1969)? Even Loach had fallen into

the cinematic wilderness at this point in his career and was working only sporadically

in TV. So my hopes were high when I queued up to buy

my ticket for Scum. I emerged from

the cinema bristling with excitement. After close to

a year made up largely of mainstream Hollywood products, this

was a thumping kick in the bollocks, brutal and confrontational,

but also intelligent and searingly well directed and

acted. It seems ironic that this cinema feature was

my introduction to the work of one of the country's

greatest directors of televisual drama, Alan Clarke.

Scum was Clarke's first film made specifically for the cinema,

but was never intended to be that way, having been commissioned

as a TV play and then banned (for more details of this

and an outline of the plot, see my review of the BBC

version). The feature was effectively a

remake of this, using the same script and employing many of the same actors, but with a few crucial changes. The

most obvious one to those who have watched the TV version

first is the stronger language. Some have seen this

as part of a the process of sensationalising the story

for the wider cinema audience, but I could not disagree

more – in the original, racial abuse is used as a method

of verbal bullying by guards and inmates alike and

the swearing is a logical and non-racial extension of

that; had the TV play been made ten years later when

restrictions on language had been eased for British

television, then I have no doubt that this is how the

script would have played from the start. Indeed, given

the characters and the environment, the idea that such

language would not be used is patently absurd,

and its inclusion here adds to both the realism and

menace of the threats and has contributed to most of

the film's most quoted lines. Carlin's confrontation

with rival black 'daddy' Baldy, for instance, is transformed

by just one word: "Where's your tool?" "What

fucking tool?" Wallop. "THIS FUCKING TOOL!"

Now THAT is a threat.

Crucial

to selling this, though, are the altogether more confident

performances of the leads. No longer first-timers and

well rehearsed in their parts, they now inhabit their

roles as if born to them. This is especially evident

in Ray Winstone's electrifying performance as Carlin

– where his more low-key delivery worked perfectly for

the matter-of-fact approach of the TV play, his burning,

ferocious anger here propels the story forward like

a bulldozer on steroids. Nowhere is this more evident

than in the scene in which he confronts and defeats incumbent

daddy Banks and his cronies – this was always a great

scene, but Winstone's calm tooling-up at the snooker

table ("Yeah, well, carry on"), the viciously

physical beatings

and his furiously delivered pronouncement to the defeated

Banks, "I'm the daddy now! Next time I'll fucking

kill you!" leaves you in no doubt that from now

on Carlin is in charge and that it's going to take a force

of some considerable power to dislodge him. It is no

small testament to my identification with Carlin that

when I first watched this scene I nearly stood up in the

cinema and cheered. Looking back, this generates the very

same visceral power as when John C. Macreedy suddenly unleashes his jujitsu skills in John Sturges electrifying Bad Day

at Black Rock (1955). No surprise, then, that on the commentary tracks

of both this and the BBC version, host Nigel Floyd draws

comparisons between Scum and classic

western plots and characters.

Once

again, the flipside of Carlin's power-though-aggression

approach is Archer, the intellectual misfit determined

to cause as much trouble for the system as he can using methods that his custodians, particularly the overtly religious governor,

have no experience of handling. He was played in the original by David Threlfall, but his contract with the Royal Shakespeare

Company forced a re-casting, and here Clarke struck

gold with the talented Mick Ford, a young actor relatively new to

film and TV (his only previous film role was in Jack

Gold's The Sailor's Return the previous

year) who works such wonders with the role that he almost

steals the film from Winstone.

His cocksure gameplaying with the routines imposed on

the inmates is both hilarious and inspiring, a smart and

non-violent fuck-you to a system that only knows how

to respond with aggression.

Personal favourite Archer moments include the comically mannered delivery of his name and number when

called before the governor, whom he

then outrages by claimeing he feels drawn to Mecca; the drawn-out

pronunciation of the word "Trust" when baiting

the Matron during a discussion period (his qualifying

explanation suggests an intellectual superiority on his part that

she clearly finds intimidating); and the painting of

the words "I am happy" on a wall he is supposed

to be decorating. Ford's interpretation of the role

differs from Threlfall's enough for both to be enjoyed

for different reasons – my preference for Ford's interpretation

is no slight on Threlfall, its just that at times

the Archer played by Mick Ford reminds me of me, at least it would had

I even a fraction of Archer's self-control and natural cool.

The

supporting cast are as impressive as they

were in the original, the one notable improvement being Richard Butler's delicious turn

as prison Governor Mr. Baildon, replacing the original's Peter

Powell and clearly relishing the lines

given to him by Minton, investing almost every word

with an extraordinary degree of self-righteous judgment.

His delivery turns even the straightforward into something memorable: just listen to how he says the single word

"Indeed" when confronted with Archer, a word

that simply slipped by in the original. Few who have

seen this version will not smile at the memory of "Ah,

Archer," or "We'll have no more talk of MECCA!"

Matching

this increased confidence on the part of the actors

is Clarke's sometimes more animated direction. I've

met very few film-makers who would not relish a second

stab at a cherished project, and this includes the Hollywood

exulted, evidenced by Spielberg's re-working of Close

Encounters and George Lucas's endless tinkerings

with the few works he has directed. Clarke takes

this opportunity not just to adjust his camera placement

(witness the telling reverse of angle on Carlin after

has asked for a single cell and is dismissed by the

warder advising him to watch his step), but also the handling

of some key scenes. It is here that the director began

to experiment with his 'walking shots', long takes following

characters as they move between locations, most effectively

used to focus on Carlin when he seizes power from Banks.

This adds an undeniable urgency and vigour to an already

gripping scene and was a signpost of things to come,

when Clarke would later shoot entire films on Steadicam

using walking shots (although the Steadicam was invented

and in use by now, the walking shots in Scum were done hand-held), culminating in extraordinary, groundbreaking works like Road and Elephant.

Another

area in which it was claimed that the feature sensationalised

a story told with more subtlety in the TV play is the

upping of the violence, but this simply isn't

the case. Key scenes used in evidence include the greenhouse

rape and the suicide of Toyne following the death of

his wife, but both scenes were in the original and fell

victim to post-production trimming (the rape was shortened,

the suicide completely removed) in an effort to appease

those wanting to stop it being shown. Indeed, I would

argue that Carlin's bathroom assault on Banks is more violent in the original, the initial ramming of his

head into the sink being shown in close-up, whereas here

it is covered in wide shot. Both the notorious murderball sequence

and the final riot are virtually identical in both versions

(right down to the kinetic tracking shot during the pre-riot

"Dead!" chant), and lest there be anyone out

there in these more cautious times who believes the

murderball match is a flight of fancy on the part of

the writer and director, be advised that we used to

play it once a term at my humble comprehensive school

– and it really was that violent every time.

What

surprised me most watching Scum again

for the umpteenth time is how much of a wallop it still

packs. With too much British cinema consisting of either

twee middle class romances or ludicrous mockney gangster

dramas, Scum is still around to remind

us that once upon a time British cinema was urgent,

realistic and had something worth saying. It also had

balls the size of asteroids.

For

anyone familiar with the now budget-priced UK release

of the film from Odyssey Video, the print on the Blue

Underground disc is going to come as a major revelation.

Where the Odyssey print is framed 4:3, grainy, and blighted

by a few scratches and dust spots, this new Blue Underground

transfer, released as part of The Alan Clarke

Collection, is as close to perfect as you could

hope for a low budget British film from the late 70s.

Framed 1.66:1 and anamorphically enhanced, the print

is clean and sharp, with spot-on contrast and colour. Grain is still evident, but minimal and

never intrusive. A very nice job indeed.

There

are three sound mixes available: the original mono, a Dolby

2.0 surround track and a 5.1 remix. Obviously the mono track

is the most faithful to the original release, and as with

the BBC version the on-location recording was first-class and is cleanly reproduced here. If anything, I'd

say the location recording on the original BBC version actually

has the edge on this one, at least in terms of clarity and

acoustics. The Dolby 2.0 track has better fidelity and spreads

the still essentially mono sound across the front soundstage

a bit more, while the 5.1 track has just slightly more clarity

and pushes some ambient sound to the rear speakers,

though you have to stick your ear against them to hear this

most of the time.

The

menu offers English subtitles only, but there seem to be

two subtitle options once in the film, both English and

identical to each other.

The

key extra feature on this disk has to be the commentary

track with lead actor Ray Winstone, hosted

by Nigel Floyd. Putting aside the fact that it appears

to have been recorded in an empty warehouse (at one point

you can hear some drilling going on somewhere in the background),

this is an excellent track – Winstone is still as down-to-earth

and direct as ever and has plenty of great anecdotes

about the filming. Some of them are well known, such as

Clarke's way of firing up the actors for the murderball

sequence, while others – when actor John Judd (playing

warder Mr. Sands) got a bit 'realistic' when losing his

rag at Banks for letting Carlin beat him and feared genuine recrimination during the riot scene – were new to me. The language

is stronger than on most commentaries, stronger than the

film in places, but this adds to the sense that you're

sitting down with Winstone for a pint and a chat about

the film. Initially busy, it trails off a little towards

the end, but is still a fine inclusion.

Also

included are Interviews with producer Cliver

Parsons and writer Roy Minton. Running a

total of 17 minutes, this extra has been transferred over

from the 1999 Odyssey region 2 release and is very honestly

announced as a pair of EPK interviews. Shot on video and framed

4:3, it includes extracts from the film, giving you the

chance to compare how it used to look on DVD before Blue

Underground got its hands on it, though they do take up a sizeable

chunk of this extra, too much in places (notably Archer's

talk with Mr. Duke, which is shown in its entirety). The

interviews themselves are very worthwhile – Parsons gives

some useful background on the genesis of the film version

and the controversy that followed its release, and Minton

muses on one of the key differences between the BBC and

film versions. Both men offer interesting retrospective

viewpoints on the film and its characters.

Poster

and Stills Galleries includes 3 posters for the film (including one for a double-bill

with Quadrophenia which I still own),

32 production stills (which are reproduced at a decent

size) and 4 video covers.

Finally

there is the Theatrical Trailer,

which is framed 1.85:1, anamorphically enhanced and in

surprisingly good shape. Interestingly it has a music

score, while the film itself has none, and a voice-over

recorded by Ray Winstone as Carlin specifically for the

trailer. It runs for 3 minutes 15 seconds, is edited in

a most rudimentary style, but still sells the film quite

well.

It still has its naysayers, but for my money Scum

is one of the finest British films of the 70s, which makes

it one of the greatest British films of modern times, end

of story. Although already available on a now budget price

UK DVD, Blue Underground's version blows it out of the water

with its pristine anamorphic transfer, its multiple soundtrack

options and its fine commentary track, and it even includes

the interviews from the UK release. Following on from the

inclusion of the BBC original, this is reason 2 of 6 to

immediately buy The

Alan Clarke Collection.

|