|

It really is worth remembering that back in 1978 before the release of Halloween, one of the most celebrated of all modern horror directors was not condsidered to be a horror director at all. Indeed, on his home turf at least, the name John Carpenter wasn't that well known. That was about to change.

Having made 8mm films in his early teens, Carpenter's film career began while he was at the University of Southern California, where he and fellow student Dan O'Bannon began work on a satirical science fiction short entitled "The Electric Dutchman", a project that consumed so much of their time that they eventually abandoned film school to complete it. They spent the next year creating what ultimately, with additional funding provided by porn and exploitation magnet Jack H. Harris, became known as Dark Star, a gloriously witty and inventive gem whose release was held up by a legal quirk* and did precious little business when it did hit US theatres. A Christmas TV screening and subsequent cinema release in the UK, however, attracted almost universally positive reviews, and found the film a wider and more appreciative audience.

Disillusioned by Dark Star's box-office failure, Carpenter turned to scriptwriting as a possible way into the film industry. Two of his early screenplays were later turned into features – Black Moon Rising was directed by Harley Cokeliss in 1986 and starred Tommy Lee Jones and Linda Hamilton, while Escape From New York became one of Carpenter's own early projects. One other such script was initially titled "Eyes" and featured a woman who is intermittently able to see through the eyes of a serial killer who is murdering people in her home town, and who slowly appears to be heading in her direction. Carpenter took the script to Jack H. Harris, who passed it on to soon-to-be hotshot producer Jon Peters (later of Flashdance, Rain Man and Batman, amongst others). Peters expressed interest in making the film, but only if Carpenter could rewrite the story to make the killer someone that the lead character knew and who possibly even loved her, adding unnecessary whodunnit and romantic elements to what was initially designed a straight-up thriller. Despite his attempts to convince the studio that the film would be far more effective without such pseudo-psychological baggage, Carpenter eventually re-wrote the script and then walked from the project, forgoing the opportunity to direct the film that could have effectively launched his career. The screenplay was further reworked by four more (credited) writers and made it to the screen in 1978 as The Eyes of Laura Mars, directed by Irvin Kershner and starring Faye Dunaway and Tommy Lee Jones.**

Carpenter then began promoting himself as more as a director than a writer and eventually struck lucky when a backer approached him with the money to fund a low budget feature, which resulted in the brilliant urban western, Assault on Precinct 13. Astonishingly, at least in retrospect, what should have been Carpenter's breakthrough film also failed to make an impression at the US box office, but a triumphant screening at the London Film Festival and some strong British press reviews were followed by a far more successful UK cinema release.

This positive response eventually filtered back across the Atlantic, where Carpenter landed a deal to develop three projects for Warner Brothers Television. A thriller titled "Prey" ultimately came to nothing, while the beach party comedy Zuma Beach was ultimately developed by other writers and given to Lee H. Katzin to direct. But the third, Someone's Watching Me! (originally Highrise, a frankly smarter title) was not only written but directed by Carpenter, and remains one of his most criminally unseen works. A Hitchockian thriller with a strong Rear Window influence, it tells the story of a female TV producer (played by Lauren Hutton) who discovers that a number of the previous tenants of her new apartment died by their own hand, and begins to suspect that someone is spying on her from the apartment block opposite. Although made for TV, it proved an important film for the young director, as it's here that he was first able to develop the concept that was central to his version of The Eyes of Laura Mars in the way that he wanted and pit a strong female lead against an unknown killer without studio-imposed distractions.

By the time Carpenter came to direct Highrise, he had already started writing what was to become Halloween with his then girlfriend, Debra Hill, who also served as the film's producer. It all began when independent producer Irwin Yablans and financier Moustapha Akkad saw Assault on Precinct 13 at the Milan Film Festival and approached Carpenter with the money to make a low-budget thriller about a psychopath who is stalking babysitters, provisionally titled "The Babysitter Murders". Carpenter agreed to write and direct as long as he would have complete creative control and that between them they could come up with a better title. Carpenter recalls:

"He [Yablans] called me one night and said, 'What would you think about having it happen on Halloween night and calling the movie Halloween?' That was his idea, and suddenly the movie all took shape for me, and I said 'That's it.' I've always loved Halloween, and what I wanted to make was the king of that sub-genre horror movie about the psychopath, but at the same time explore the whole feeling of Halloween night."***

This was the first time Carpenter worked professionally with Hill, a partnership that continued on The Fog, Escape From New York and the script for Halloween II. It also marked his first collaboration with cinematographer Dean Cundey, who would go on to shoot a further four features for the director. And after pretty much going it alone on Highrise, here Carpenter was able to bring a few of his friends and former colleagues on board, including childhood pal Tommy Wallace, friend and fellow USC student Nick Castle, and actors Charles Cyphers and Nancy Loomis from Assault on Precinct 13.

The shoot was one of the smoothest that Carpenter can recall, and the finished film was a runaway success with audiences and – after some initially dismissive responses – critics alike. Despite being shot on a budget of just $325,000, Halloween went on to gross over $47 million at the US box office alone, which to this day makes it one of the most profitable independent films ever made. It enhanced Carpenter's growing cult status and did more than any of his previous films to launch his career as a director. This was cemented by the unexpected success of his next film, the made-for-TV movie Elvis, which on its first screening pulled a bigger audience than both Gone with the Wind and One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest, against which it had been riskily scheduled.

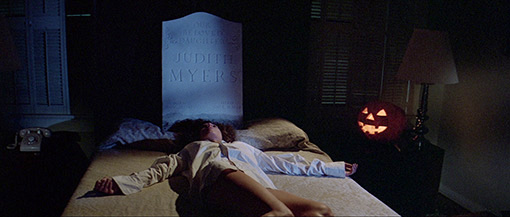

If, by some chance, you've never seen seen Halloween or even read that much about it, a simple plot summary might be in order. On Halloween night in 1963, 6-year-old Michael Myers inexplicably stabs his older sister to death. Fifteen years later, he escapes from the hospital to which he has been confined, and noted psychiatrist Dr. Sam Loomis, who has become convinced that the adult Michael is a human incarnation of evil, travels to Michael's home town of Haddonfield, Illinois in the hope of apprehending him. In this very same town, shy high school student Laurie Strode and her more outgoing friend Annie are due to spend this Halloween night babysitting at oppositely located houses in the same street, a situation their gregarious friend Lynda plans to take advantage of to get bedroom time with her boyfriend Bob. As Loomis tries to convince Sheriff Leigh Brackett of the potential danger facing his small town, Laurie becomes convinced that she is being watched and even stalked by a mysterious figure. Her claims are dismissed by her pitying friends, but that night they are all made very aware of the threat that Michael represents.

Halloween is now thirty-five years old and has been the subject of extensive analysis, fan appreciation, articles, interviews, dedicated web sites and retrospective reviews over the years. Back when I first wrote about it (at some considerable length, I should add), my research material was restricted to contemporary reviews and interviews with Carpenter and Debra Hill, usually in periodicals that you could only access on microfiche (look it up) at the BFI Library in London, a building in which I spent many a long and studiously blissful day. Coming back to it now, I am all too aware that there's likely nothing I can say that hasn't already been said a good many times, but feel the need to say it anyway. The film was too important a part of my youth and horror viewing to be summed up in a couple of quick appreciative paragraphs. This is thus likely to be one of those long but hopefully not too arduous reviews that tends to define this site (and remember, we're still on the introduction here). Fellow fan Camus kicks off with his own appreciation, after which I'll try and explain just why I believe Halloween is the very definition of a great horror film. Be warned, however, we are going on the basis that you know the film, and there are thus likely to be a few spoilers ahead.

There is an exquisite irony in the fact that a film famous for its almost total lack of gore is credited as the one movie that gave birth to all manner of explicitly horrific and crimson soaked, slashed viscera-fests. In some ways, Halloween is the safest scare you could wish for. Its thrills, suspense and audience jolts are so well timed and crafted, they have no need for any explicit body mutilation. In this sense, it's clean horror, underlined by the hyper-normal suburban setting and ratcheted up by the supernatural invincibility of its antagonist. Michael Myers is the real boogeyman and is dressed and masked for the occasion. A boiler suit and a blank face (a restyled William Shatner mask) allow us to imagine all souls (how appropriate) on to this shape that keeps curtaining in from the sides of frames to keep our anxieties bubbling. Halloween is the ultimate "Boo!" movie despite its B-Movie budget.

Do I need to give you a summation of the plot? A certified nut-job escapes from his psychiatric hospital and returns to the town of his first murder to murder again. Not wishing to dent the movie's allure in any way but that's about it. It's all in the tagline... "The night HE came home..." After my umpteenth viewing, I've discovered that my relationship with the film had become a very personal one. I found certain details, lines of dialogue, items of wardrobe and suchlike immensely reassuring. This is usually not good for a scary movie but you can elicit an almighty grin from me just by showing Jamie Lee Curtis in those woolen tights clutching those books to her chest. It's Wardrobe 101 for telling us we are in the presence of a geek, a shy, bashful girl who nonetheless does reveal sputtering sexual stirrings. Ironic indeed that Curtis went on to represent a specific female type in 80s cinema, someone confident, hyper-sexy, brash even and extremely comfortable with her body. She was never going to lack a genetic pedigree. Her parents were both fully-fledged movie stars, Tony Curtis and Janet Leigh. It helps to push your little, low budget shocker if your star is the daughter of the star of the grandfather of the slasher movie, the inestimable Psycho. Apparently, before casting, Carpenter didn't know her family tree...

I'm going to rely on fellow scribe Slarek to peel back the layers and flag up the subtext despite Carpenter's assertion that it's just a horror movie. No such thing. Horror movies have subtext bursting out of their chests. I'm just going to share those moments and memories that keep Halloween lodged in my once teenaged mind (and it's still there). Once Michael is revealed after the first murder, Carpenter cranes backwards and upwards while a disbelieving mom and dad stare at their offspring (as shots like this invariably force the actors to do for a lot longer than any human being would do in reality). I would have tried another take (who knows how many times this was shot?). The one small change I'd make would be to ask the mother of evil not to put her bloody hands in her pockets. She looks like a bored teacher admonishing a pupil, not a disbelieving parent seeing her son with an incriminating and bloody weapon in his hand... As we move back, she actually puts her hands in her jacket pockets and this must have been Carpenter's direction as it's such a big move in his end of sequence shot. Funny, the things which bug you in such a beloved movie.

Once we're with the only man on the planet who knows how dangerous Michael is, Donald Pleasence's Dr. Sam Loomis (another nod to a character in Psycho), Carpenter fills the frame with blackness, places where evil always lurks. His framing in the 'Michael escapes' sequence invites us to guess at the moment when 'the shape' will make an entrance. A hideous amount of black in the frame makes us imagine all sorts of horrors are going to leap out. And leap out they do. I was even caught unawares seeing it recently, shocked by one moment in the film I'd completely forgotten and that must have been my twentieth viewing. The fear is still there and the movie still works gangbusters. Of course, every single horror cliché is enacted in Halloween, including our heroine looking behind her, turning to walk on and being stopped by someone standing in front of her (that's a cracker) and perhaps the silliest but still effective, the spider like fingers on a character's shoulders making everyone jump. But they weren't clichés then as much as they are now. And Halloween is partly the cause of that.

As much as anything, it's the musical stings that make us jump and Halloween is blessed with what is now regarded an iconic score. In 5/4 time, the minimalist higher note key tapping synth background with the low ominous through line is such a perfect low budget match to his visuals, it sets the film apart from the very start. Classical minimalist Philip Glass was still finding his feet in the late seventies but Carpenter had beaten him to it. Movies today seem to eschew themes (or so I believe as I rarely hear good ones in horror movies any more). Carpenter used real music and themes to electrify his shocker despite his modesty about his composing and playing skills. In terms of the music working so well with the visuals, Carpenter's Halloween is right up there with Jerry Goldsmith's terrifying work for both Alien and The Omen, Bernard Herrmann's string themes for Hitchcock's Psycho and Goblin's irresistible chanted mantras in Argento's Suspiria. "Witch!" I'm not elevating Carpenter as a composer who can match other composers' output but in terms of iconic acceptability, his score for this delightful shock machine is absolutely perfect.

There are many details that escaped me over the years but now, observing rather than just watching, there are aspects that wool-like stick to the barbed wire of my curiosity;

-

Donald Pleasence is parked in a handicapped parking space in the hospital for no other reason (as is my guess) that the one Panaglide shot would not work unless his car was parked closest to the building standing in for the mental asylum Michael escaped from. It would have been an idea to hide the sign maybe? Or get Pleasence to limp?

-

The word 'totally' overused by one of the murdered girls which in 1978 was the ubiquitous equivalent of 'awesome' today.

- The instatement of the crass idea that having sex marks you for death. Boy, did that cliché get old fast.

-

The exquisite timing of Michael's car as it passes behind Pleasence looking out both left and right for anything unusual.

-

Donald Pleasence's extraordinary performance – over the top yet constrained. Hampered by some absurd dialogue (hey, it worked, it's not a criticism just a failed attempt at objectivity), he moves through the movie, the sanest man of science tipped into rampant paranoia by a belief in the impossible – a man, evil incarnate whom no one can kill. A perfect antagonist for a recurring franchise, methinks.

-

Laurie... DON'T KEEP THROWING AWAY THE BLOODY KNIFE!!!

Halloween is, of all things, fun. Like the Mac used to be, Halloween is the horror movie for the rest of us. Horror is fun. Wait. Horror can be fun. Better. And to paraphrase a ghastly Apple commercial guilty of murdering only the English language, Halloween is the funnest horror movie ever made.

| |

|

| |

"Carpenter uses every trick in the book, and more besides, but does it all with freshness and vigour. His camera technique and scene construction are both object lessons. He even has the nerve to set up scenes of breathtaking naivety and yet somehow manages to get away with them. He has the knack of making the incredible look very credible indeed." |

| |

David Hughes – Western Mail |

| |

"It is one of cinema's most perfectly engineered devices for saying "Boo!'" |

| |

Richard Combs – Monthly Film Bulletin |

Watching Halloween for the first time back in 1978, I experienced something I've rarely felt in a cinema – genuine, white-knuckle fear. As a horror fan of many years standing you'd think I'd be familiar with this particular sensation, but there are precious few films that have actually had me chewing my nails and shrinking in my seat, at least since my childhood. That's where my love affair with horror began, as it did with so many of my generation, with furtive viewings of classic Universal horrors on late night TV, an experience enabled by a sympathetic babysitter. It's back then that I learned the exquisite perversity of being scared silly by a film that you immediately wanted to watch again. But by the time I was (erm, almost) old enough to see these films legally, I'd seen enough of them to take manufactured tension in my stride. I'd still get wound up, but that seat-grinding fear that first hooked me on horror was a delicious but too-rare experience. But when young Laurie Strode ventured into the darkened house in which her friend is supposed to be babysitting and started hearing noises upstairs that you just know are being made by the killer, I was ready to drop my rubbish on the spot. Yet this was nothing compared with the ten unbroken minutes of unrelenting terror that then followed.

My reaction was far from an isolated one. In subsequent screenings I witnessed audiences screaming and physically leaping in their seats so violently that they sometimes almost ejected me from mine. In what in retrospect seems like a slightly perverse move, I later took my two younger sisters to a Carpenter double bill consisting of Assault on Precinct 13 and Halloween (they were both film fans and I'd been banging on about these two movies for months). Back in those days, films often played as double-bills and you could enter the cinema at any point in the programme and leave when you pleased (I watched a fair few films twice over thanks to this), and a quirk of timing sat us down in front of Halloween first. As that final ten minutes unfolded, both sisters were screeching helplessly, and as Laurie ran for her life and scrabbled hopelessly for a potentially life-saving door key, one of them turned to me and urgently squealed, "If this carries on I'm going to wet myself!"

I was well aware of the work of John Carpenter by then. I'd missed the BBC Christmas screening of Dark Star due to attending the third night of a newly released little film called Star Wars, but caught it on the big screen on a peculiar double-bill with John Borman's Zardoz. Not prepared to wait until it made its way to one of the bigger local screens, I saw Assault on Precinct 13 in the smallest cinema I've ever paid to sit in, and by the time Halloween arrived in the UK I'd already seen Assault a further eight times. In the year or so that followed I saw Assault on Precinct 13 and Halloween, often together (still have the poster for that particular double-bill), about twenty-five times and wrote my film school thesis on the early work of this exciting new director. No doubt about it, Halloween was one of the most important films of my teenage years.

It was only on these subsequent viewings that I really got to appreciate the extraordinary artistry and craftsmanship that went into the film's construction. Being film students we were all blown away by the stunning opening Panaglide drift through the Myers house (actually a composite of two separate shots, but the transition is seamless), but there is so much here that plays like a masterclass in how to direct a low-budget horror movie. And with apologies to Camus, but for me this is one horror film that is exactly what it purports to be, and just this once any discovered subtext I'd suggest really would be in the mind of the beholder.

Boasting the structural purity that was stripped from Carpenter's original concept for The Eyes of Laura Mars, Halloween breaks down the thriller to its basic components, pitting a faceless, emotionless and seemingly unstoppable male monster against a shy and virginal female high school student, seemingly impossible odds that cement audience loyalties at an early stage. But there's so much more to it than that. Unlike the leads of the slew of slashers that floundered in Halloween's wake, the teens in Halloween are not psycho fodder shaped for the audience to cheer the demise of. Lead girl Laurie is instantly likeable and her two closest friends are both annoying in interesting and engaging ways. In some respects the two are polar opposites – Annie wears her cynical world-weariness like a second skin, while Lynda bubbles with the sort teenage enthusiasm that suggests there is no part of her life that doesn't have a cheery upside. Distinctive though this makes them, you can't help wondering how these three actually became friends in the first place.

That they register so quickly and effectively can be attributed to four crucial elements that the film's would-be imitators have tended to leave at the door: script, casting, performance and direction. Seems obvious, doesn't it? But it's a failure on two or more of these counts that has caused so many subsequent low-budget horrors to fall on their faces. Dialogue is far more than functional here, helping to shape character and to subtly telegraph where events will later take us. Even the seemingly inane chatter between the girls is wittily written (Carpenter credits Debra Hill with really nailing the fine detail of the female characters), right down to Lynda's trend-driven habitual use of the word "totally" (just two weeks ago I was walking behind two American girls and overhead one of them respond to a statement made by the other with "Oh, she was totally wrong about that" and found myself quietly giggling with glee).

It helps that these roles are so sublimely cast. As the sardonic Annie, Nancy Loomis may be partly re-running her role as Julie in Assault on Precinct 13, but she still delivers some of the film's most memorable character moments, from her wonderfully pitying "Poor Laurie, scared another one away" to her too-late "hang on a minute" realisation that a previously locked car door is now open. As the perennially upbeat Lynda, meanwhile, P.J. Soles does wonders with the closest the film has to a stock teen role, notably her gradual metamorphosis from tarty flirting to wide-eyed annoyance when she mistakes a sheet-covered Myers for her boyfriend Bob. It's this film, together with her scene-stealing turn in Carrie and her effervescent lead performance in Rock 'n' Roll High School, that landed her a small but devoted cult following.

And then, of course, there's Jamie Lee Curtis. There's little I can say in praise of Jamie Lee here that hasn't been said many times already, but as a feature lead debut this is up there with Sigourney Weaver in Alien. Her pitch-perfect underplaying makes Laurie one of the most convincing female leads in modern horror cinema, a role that proved a defining one for Curtis and a kicking-off point for Carol J. Clover's Final Girl Theory. And she really is superb here, from her interplay with the kids (her disbelieving eye roll and shrug when Lindsay sides with Tommy after he complains that no-one believes him is a memorable highlight) to her horribly convincing screams for help and whimpers of terror during that final ten minute onslaught.

The rest of the cast are every bit as carefully chosen. Camus has already sung an appropriate hymn to the great Donald Pleasence (though he is the only one here who seems to know he's in a horror film), whose final, searching look skywards is such a sublime blend of disbelief, wonder and dread that it has become one of my favourite moments in the film. Carpenter regular (and the only one of his previous collaborators who worked on Highrise) Charles Cyphers again gets to play the gruffly cynical cop, but does so with aplomb, displaying his impatience at Loomis's almost theatrical warnings with a dismissive "More fancy talk," but bringing real gravitas to lines like: "All right, I'll stay with you tonight. Just for the chance that you are right. And if you are right, damn you for letting him go." Even the kids make an impression here. Young Brian Andrews makes it easy to sympathise with Tommy when Laurie refuses to believe what he claims to have seen, while 9-year-old Kyle Richards (sister of Kim, who played the little girl shot by Street Thunder in Assault on Precinct 13) even pulls off a couple of moments of sly comedy after Annie gets caught in the window whilst trying to escape from a mysteriously locked washroom.

But what made Halloween such a dynamite thriller in 1978 and continues to make it so rewarding today is Carpenter's direction, and I mean that in all of its facets, from his pacing and scene construction to his handling of the actors, canny camera placement and savvy editing decisions, although cinematographer Dean Cundey and editors Charles Bornstein and Tommy Wallace also deserve serious credit here. While the film may kick off with an attention-grabbing bang – something that has become almost de rigueur in modern horror cinema – it is at least a stylish and purposeful one, with the portentous night-time visit to the psychiatric hospital that follows delivering a couple of good scares as its sets the plot rolling.

But once we meet the girls, Carpenter is in absolutely no hurry to unleash homicidal mayhem. As Camus states above, there's an irony to the fact that the film that is credited with giving birth to the slasher sub-genre is virtually blood-free. Then again, I've always questioned Halloween's status as the slasher film's godfather and tend to credit Sean S. Cunningham's Friday the 13th with that dubious honour, though it is worth remembering that Cunningham's film was created for the sole intention of cashing in on the box-office success of Halloween. But where visually gruesome murders are almost the raison d'être of the average slasher film, in Halloween they are not only events to be feared but visually unspectacular when they do occur, an obliquely shot throat cutting, an off-screen stabbing and a strangulation by telephone chord. And leaving aside the opening sororicide story-setter and the briefly glimpsed body of a luckless truck driver, we're 55 minutes into this 91 minute film before the first murder even takes place.

For its first two-thirds, Halloween is effective slow-build, a portrait of everyday life for Laurie and her chums punctuated by moments of troubling unease. To this end Carpenter employs a variety of tricks old and new, from the backwards walk into a stationary figure (seriously, one of the best scares of the decade when you see it on a cinema screen for the first time) to the sort of now-you-see-him-now-you-don't effect that can only be achieved on the editing bench. False alarms are sometimes underscored with humour, and several jolts are accompanied by a loud synthesised bang, the only thing in the film that now feels a little overstated (though it worked a treat at the time). Where Halloween shines, as I've intimated above, is in slowly building this sense of unease to point where it slips almost invisibly into seat-grinding tension, as Laurie flees from the house of death, relentlessly pursued by a killer who marches steadily towards her like a pre-programmed Terminator that utterly refuses to lay down and die. It's a brilliantly shot and edited sequence where just everything contributes to one of the very best wind-ups in horror film history: the cross cutting between the frantic Laurie and the steadily advancing killer; filming the killer's approach in wide shot solely from Laurie's point of view; Tommy's slow and sleepy response to Laurie's frantic screams; the switch of viewpoint as the tension peaks to place Laurie outside with the killer as Tommy ambles over to open the door.

And then there's the music. Like the score for Assault on Precinct 13, this was Carpenter's own work, a pragmatic solution to a music budget of just $2,500, but also an essential element of what defines Halloween as a John Carpenter Film. And as Camus observes above, this most iconic of horror themes is breathtakingly minimalist, an electronic ticking accompanied by a repeating piano riff constructed of just three notes that shift in pitch twice before circling back to the start, layered with three more on a deep bass synthesiser. Seriously, I can even play it on the keyboard app on my iPad (it was also the first thing I ever programmed using the 'Beep' command in BASIC on a Sinclair Spectrum computer – Camus's Sinclair Spectrum if I remember right). But it gets better. One of the most effective themes of all, the one that accompanies the assault on Lynda and the subsequent pursuit of Laurie, consists of just one note, a repeating "dun, dun-dun" that is eventually accompanied by a second, higher pitched and repeated single note and a solitary chord of electronic strings. Structurally, there's little to it, yet in terms of the effect it has on the tension of those particular scenes, it borders on genius.

Of course, so influential was Halloween on subsequent horror cinema that it's nigh-on impossible to watch it today and experience it the way we did back in the late 70s, as what once seemed fresh has been so often imitated that many of its key components have become genre clichés. Even I've seen it too many times now to recreate that once delicious level of reactive fear. But I still adore it, every beautifully composed Panavision shot, every menacing Panaglide drift, every smartly written and delivered line of dialogue, every gloriously constructed wind-up and every loudly delivered shock. All fans of the film have our list of favourite moments, many of which have passed into horror film legend, from memorable lines of dialogue to heart-stopping scares. That the mask worn by Michael is the whitewashed face of William Shatner is now well known, as are the character name nods to Carpenter's favourites films and filmmakers (Sam Loomis was Marion Crane's boyfriend in Psycho, Leigh Brackett the screenwriter of Rio Bravo, which Assault on Precinct 13 was a partial remake of), and with no way to sum up that won't end in another round of heartfelt superlatives, I figured I'd end on a few favourite moments of my own. Some are well known, but a couple of the others are just a little geeky:

-

The strangely perfect marrying of image and sound as the camera tracks alongside the wire fence of a schoolyard, and the bell announcing the end of the school day feels almost as if it's being generated by the camera movement and the pattern of the fence;

-

The track back from Laurie after she has seen Michael watching her from the garden, when the telephone drifts into the bottom right corner of frame just before it rings;

-

The way Laurie pronounces "Laser Man" and "Tarantula Man" when leafing through Tommy's comic books;

-

Annie's response when she shouts at Michael's car and it stops for just long enough to rattle the girls: "I hate a guy with a car and no sense of humour";

-

The way the soundtrack of a TV screening of Forbidden Planet turns a wide shot of Michael carrying Annie's body into the house – as seen from Tommy's viewpoint – into an almost supernatural vision, transforming Michael into the boogeyman of Tommy's fears;

-

Laurie, Tommy and Lindsay walking slowly through the house with a pumpkin making "Woooo" ghost noises;

-

The way just two words – "The keys!" – manage to up the level of terror of the chase from the death house by a good three notches;

-

The petrifying sight of Michael's arm bursting through the kitchen door and scrabbling for the lock;

And my absolute favourite...

- The extraordinary image of Michael, having nailed Bob to a cupboard door with a kitchen knife, moving his head slowly side to side in what I once took to be a look of confusion (given that he seems to be killing effigies of his sister, he seemed bemused by this unexpected male victim), but which Carpenter himself suggests is closer to that of a lepidopterist studying a freshly pinned butterfly. Now how creepy is that?

A low budget film Halloween may have been, but it was shot on 35mm on Panavision cameras and so there's absolutely no reason why it shouldn't scrub up well. The restoration here was made from the original source material under the supervision of John Carpenter and DoP Dean Cundey, and is just the sort of transfer fans have been hoping for. Boasting a finely balanced contrast range in the daylight scenes and inky blacks at night without sacrificing crucial detail, the image here is crisply detailed with a fine level of film grain and no obvious signs of edge enhancement. Pleasingly, the colour timing has not been messed around with, retaining the autumnal hues of the daylight scenes and the blue and orange filtering of the night-time lighting, and low light scenes are always clearly rendered (particularly if you're watching it in a darkened room at night, as you absolutely should).

The original Dolby 2.0 mono soundtrack, itself cleanly rendered, is joined here by a Dolby TrueHD 7.1 surround remix, which I can presume is based on the 5.1 remix on the 25th Anniversary DVD, which included some new thunder and wind sound effects, all of which were added with Carpenter's approval. While the mono track is truer to the original cinema experience, the surround track has been assembled with care, throwing weather effects around the room and adding some serious bass to thunder and the music score. Pleasingly (and unlike some other surround remixes I could name), the dialogue has been kept at a level that assures that it is never feels overpowered by the effects or music.

Commentary by John Carpenter and Jamie Lee Curtis

Although Carpenter and Curtis (along with producer Debra Hill) were both on the commentary on Anchor Bay's 25th Anniversary DVD, they were recorded separately there and edited together in the Criterion manner. Here the pair have been brought together and bounce of each other wonderfully, with Carpenter's calm analysis and engaging recollections amusingly counterbalanced by Jamie Lee's sometimes effervescent energy. Her enthusiasm for the film is a barrel of fun – you can almost imagine her excitedly grabbing Carpenter's arm as she screeches "Look at this shot!" or describe a sequence as "Soooo scary!" Particularly funny is her repeated use of the term "effing" to avoid swearing, then when Annie's murder scene approaches she urgently snaps, "Fuck, I don't want to watch this!" She also describes the film as "The single most important thing that will ever happen to me." Wow. There's plenty of great stuff here, even if some of it will be familiar to long-term fans.

The Night She Came Home!! (59:43)

A video record of the only Halloween fan convention that Jamie Lee has attended after many years of avoiding them, her decision to do so shaped by her desire to raise money for her favourite charity, Children's Hospital Los Angeles. Given that it was shot by Jamie Lee's sister Kelly and her partner John Marsh, it could be viewed as a bit of a puff piece, but on the evidence presented here – and given the running time there's plenty of that – she launched herself into the task with the energy and commitment of a fired-up 18-year-old film evangelist on a mission to convert the world. Over the course of two long days she holds court to large audiences, signs hundreds of personalised autographs and has her photo taken with a stream of fans, and by the end of each day seems every bit as lively and enthusiastic as she did at the start. A couple of other actors – including a heavily bearded Charles Cyphers – also get a brief look-in, but it's primarily Jamie Lee's show. Shot on the now ubiquitous Canon 5D (well two of them actually), it's a high-res extra and the picture quality is terrific.

On Location: 25 Years Later (10:25)

An extra ported over from Anchor Bay's 25th Anniversary DVD in which producer Debra Hill and actress P.J. Soles recall shooting on location. We also get a peek at what some of the houses and streets used in the film look like 25 years after the event.

TV Version Footage (10:46)

Unlike the 25th Anniversary DVD, where you had the option to play the film with this extra footage included, this additional material shot by Carpenter for the 1981 Television Network Premiere has been collected here as an extra feature, and plays without comment or musical accompaniment. I'm happy enough with this, as none of this new footage feels like it belongs in the original film, and the sequence in which Loomis argues the case against Myers to two doctors is overlong and stilted.

We also have the scrappily assembled original Trailer (2:42), 3 similarly untidy TV Spots (0:32 / 0:32 / 0:12) and 3 sincerely narrated Radio Spots (0:29 / 0:27 / 0:28).

Yep, this is one film we can't be even remotely objective about, being too important and influential for both of us in our youth and one our all-time favourite suspense-horror movies. The transfer on this Anchor Bay Blu-ray is as good as the film has looked and sounded on home video, and the commentary is different enough in style and content to compliment rather than repeat the one on the 25th Anniversary DVD. A more thorough retrospective making-of documentary would have been nice, but this will still do me. Recommended.

* One of Jack H. Harris's more adult films became the subject of Supreme Court investigation, action that resulted in the seizing of all of his films, regardless of content.

*** I can't credit this quote because I've lost the bibliography page of my thesis (brilliant, huh?). If anyone knows where it originally appeared, please let me know and I'll add the appropriate reference.

|