| |

"We're all fucking great. You ain't taking bugger all from us, we hate you. You can lock me in here but you can't take away the hate inside my head, I can still hate you in my head. You don't like that, do you." |

| |

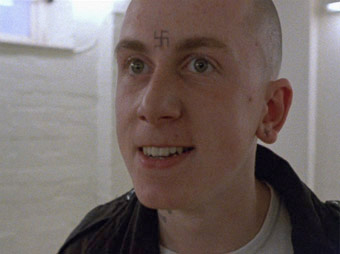

Trevor – Made in Britain |

Back in the 1970s, there was a government sponsored attempt

to boost British industry in the face of an increasing

number of cheaper imported goods by prompting a patriotic

approach to British buying habits. 'I'm Backing Britain'

stickers could be found everywhere and Union

Jack styled 'Made in Britain' labels adorned all manner

of locally produced goods. At this point in our history,

myself and many of my fellow countrymen had developed

an uneasy relationship with our national flag, something

even back then you would be pushed to find in many other countries. The Punk Generation was throwing off the

whole concept of a sovereign family and wore tattered

versions of the flag as a sign of their rejection of

its supposed values. On top of that, the Union Jack had been hijacked by the far right as a symbol

of their warped and bigoted definition of patriotism in the face of anything

they deemed as 'not British'.

It is these two representations of nationalism that

are the springboard for David Leland's Made

in Britain, one of four plays for television

screened on consecutive weeks, written by Leland under

the banner Tales Out of School and based around the

theme of education. Of the four, this was without doubt

the most controversial and confrontational. As directed

by Alan Clarke, it also became the single most electrifying television

work of the year.

After

a court appearance for smashing an Asian shopkeeper's

window, 16-year-old skinhead and habitual offender Trevor

is taken to a residential assessment centre by his social

worker, Harry. Although smarter than his behaviour suggests,

Trevor is also aggressive, rebellious and racist. From the moment he arrives, he refuses to co-operate

with those in whose charge he has been placed, and quickly lands himself in even deeper trouble with

his increasingly frustrated guardians.

One

thing that will strike any newcomer to Made

in Britain right off the bat is that Trevor is about as far as you can get from your typical leading character. He is unlikable, violent, short-tempered, self-centered

and childish, yet he is also intelligent, articulate

and rebellious. As an individual for cinematic study,

he is fascinating – but for society at large he represents

a major problem. Trevor does not so much kick against the rules

as refuse to acknowledge that they apply to

him at all, and if he does fall foul of them then he

knows how to mess with the system, or at least he thinks

he does. Like a spoilt child, Trevor is constantly demanding

things – a meal, spending money, the attention of a

job centre employee – and reacts instantly and aggressively

if he does not immediately get his way. His racism is

primitive, tribal and reactionary, a professed hatred

for those who appear different to him and who have what

he has not. Thus he throws a brick through the window

of an asian shopkeeper, but given a room with a young

black offender he immediately strikes up a conversation

with him and later involves him in a number of illegal

activities, including a further act of racially motivated

vandalism. That he verbally abuses him and ultimately

leaves him to take the rap when the two steal and crash

a van from the assessment centre appears not to be racially

driven – Trevor ultimately shits on just about everyone

he meets and would doubtless have done the same had

his companion been white. Trevor clearly likes to exercise

power, and being on the bottom rung of the social ladder,

the only way he knows how to do so is through direct

and sometimes violent confrontation with others.

Hidden

away behind this wall of anger, though, is an intelligence

and reasoning that kicks against the usual skinhead

stereotype. As is made clear in the brilliantly written

and furiously delivered monologue from which the

top quote is taken, Trevor has arrived at his present

attitude not through blind stupidity but by a process

of reactive reasoning. It is this that makes Trevor

such a compelling character and makes the film itself

so challenging, for while it's easy to warm to Trevor's

rejection of authority and to understand his angry deconstruction

of society's definition of honesty, the anarchy he represents is single-mindedly damaging and ultimately

self-destructive. Having been told repeatedly that he

is heading for a life in prison, he now accepts it as

an inevitability but has no intention of going quietly

– if he's going down, then he's going to do it his way.

Trevor is undeniably charismatic and a powerful force

for rebellion, but he is also a frightening and dangerous

figure who cannot ultimately be left unchecked. In many

ways he resembles Alex from A Clockwork

Orange – both are violent, amoral young thugs

whose intelligence and oddball charm makes them as interesting

as they are troubling. But whereas Alex's immorality is safely distanced

by the futuristic setting, his own poetic narration and Kubrick's stylised presentation

of the characters and story, Trevor is all too real.

He's the guy on the corner, down the street, next door; a

product of Right Now. Trevor is most definitely Made

in Britain – society created him and now doesn't know

what to do with him, and it is inevitable that the film-makers

have no answers to this question either. How could they? Like Alex, Trevor learns the hard way that no

matter how tough you are, there is always someone tougher

who will take you down, but unlike Alex, he does not

fall simply to rise again. Trevor is left facing a reality

that he will either learn to survive or be destroyed

by.

Made

in Britain is extraordinary television. The sheer quality of writing in David Leland's script was rare even for its time but seems completely absent

from TV today. Leland never tries to make Trevor likeable,

but by giving him such a powerful voice he forces us

to listen to viewpoints that we are deliberately made to

feel uncomfortable by. Rarely does a film of any description

dare to take on its audience on such difficult terms, feeding

them with one hand and slapping them in the face with

the other. It remains a difficult and confrontational

work, but for all the right reasons.

Similarly

uncompromising is Tim Roth's central performance as

Trevor. Roth famously only got seen at all through a

chance incident – a cycle tyre puncture led him to a youth theatre in which he had previously

worked to borrow a pump, only to discover that auditions

for the film were being held there the next day. He met Alan Clarke

and sold himself for the part. It's

genuinely impossible now to imagine the film without

Roth at its centre – his performance as Trevor is nothing

short of astonishing and is without doubt the key reason

for Trevor's enigmatic screen presence. Everything is just right here, the snarled anger, the sarcastic sneering,

the nitro-powered physicality – Roth plays Trevor as

a ball of furious energy looking for a direction in which to

explode, a missile with a message and a haphazard targeting

system. There are times when you really, really want

someone to slap some sense into him, but there is not

one solitary second that you can take your eyes off

him. When that slap finally comes, you're genuinely

unsure about how to react to it.

With

a central character this powerful and this well acted,

it's a testament to the supporting cast that they are

never overshadowed by Roth and all vividly register,

in part because of the sincerity with which their parts are

written and played. Unlike Roy Minton's script for Scum,

which had a very specific viewpoint and in doing so

cast the warders as almost unremittingly corrupt and

unpleasant, Leland takes no sides here, and if the Assessment

Centre staff and long-suffering social worker Harry

seem both well-meaning and irritable then it's because

they really are trying to help, but just do not know

how to cope with someone like Trevor. Their frustration at him comes

not from intollerence but from having to deal

on a daily basis with difficult customers, of which

Trevor is without doubt one of the most problematic,

in part because he refuses to conform to their (and

our) stereotype of an out-of-control young hooligan.

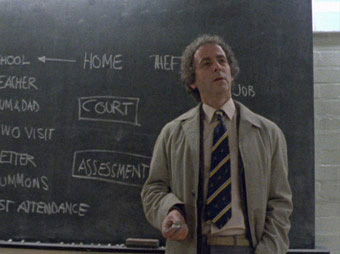

Just about the only adult Trevor actually listens to

(though he later angrily dismisses him and his teachings)

is the centre's superintendent, who, in a beautifully

written and performed scene, explains to Trevor in detail

the chances he has blown and his future options. Unfussily

shot, this is a sublime wedding of script and performance,

an object lesson to the machine-gun-editing directors

of so many modern mainstream movies in what really makes drama work.

Rounding

it all off, of course, is Alan Clarke's direction. It

was shortly before starting on Made in Britain that Clarke discovered Steadicam and for him this was

clearly a moment of liberation, the crystallisation of the style

that had been gradually emerging since Scum, one that locked on to the main character and stayed with them in a series of long 'walking shots'. This approach

is set from opening scene, in which Trevor, in constant

steadicam close-up, walks through a series of corridors

to the courtroom in which he is to be charged,

accompanied by the aggressive chords of The Exploited's UK82. It's one of my favourite opening shots

ever, a perfect blending of image and sound that iconically

introduces us to the main character and the essence

of the narrative in a stunningly economic and cinematic

way. The camera follows Trevor wherever he goes, and

when Trevor moves he doesn't hang around, but here Clarke

had an ace up his sleeve in the brilliant Chris Menges,

a hugely talented DoP and one of the first UK cameraman to

master the Steadicam. Menges locks in on Trevor and

makes him the film's key concern at all times, reflecting

the instruction to his camera operator that Clarke became

famous for: "This is your man, go with him."

Alan

Clarke was the ideal director to commit Leland's words

to film, investing in the visuals and actors the same

energy and intelligence that roars through the script. Made in Britain is an Alan Clarke film

every bit as much as it is a David Leland film and a

Tim Roth film and a Chris Menges film. It is that collaborative

process that Clarke seemed to savour, and at his best

it is not just Clarke's voice we hear but all of the

voices in the film. Made in Britain – tough, smart, angry, difficult, electrifying and without

peer to this day, is just such a work.

Made

in Britain was not only one of the first British

TV dramas to use Steadicam, it was also a front runner

in its use of new, high-speed film stocks. The allowed

Chris Menges to light locations almost exclusively with

practicals (enhanced versions of lights that would be

naturally be found in the scene), and the combination

of this and the free-floating camera gave almost complete

freedom for the actors. This faster film stock and naturalistic

approach to lighting inevitably produces an image that

is some way short of the crisp transfers we associate

with bigger budget Hollywood movies, especially given

that Made in Britain was shot on 16mm

and that sets and costumes were selected specifically for

their drabness. Given that, this is a most acceptable

transfer of difficult source material, and given the

subject matter this look actually works well for the

film as a whole. There is a bare bones, budget-price

region 2 disk already available of the film from Carlton,

which boasts a very similar transfer to the one seen

here, suggesting they were taken from the same source

(the Carlton logo remains at the end of the Blue Underground

print); there appears to be a fraction more artefact

noise on the Carlton disk, though you really have to

look for it. On transfer quality alone they are evenly

matched – it's on the extras that the Blue Underground

disk wins out. Both transfers are in the original 4:3

aspect ratio.

There's

not much to say about the sound – it was clearly recorded,

has been cleanly reproduced and is in its original mono.

A

special mention should go to the menus, which have been

executed with loving care, really capturing the flavour

of the film and the essence of the time, though have more

of a Sex Pistols punk feel than a skinhead 'Oi!' one. A

particularly nice touch is the Doc Martin boot that comes

in and shatters the main menu when you select the extras.

The

region 2 Carlton disk boasts only a trailer, but again

Blue Underground has excelled itself and produced

a disk that puts quality over quantity, resulting in a

dream come true for hardcore fans of the film in the shape

of two excellent commentary tracks. In the obvious absence

of Clarke himself, the people who you would most want

to hear from would be lead actor Tim Roth, producer Margaret

Matheson and writer David Leland, and that's exactly who

you get. Both tracks are hosted by David Gregory of Blue

Underground, a UK native who appears to still reside here

(he certainly knows more about the inside of Job Centres

than ex-patriot Tim Roth) and is clearly a serious Clarke

fan and a knowledgeable student of his work.

The

first commentary track features

Gregory and Tim Roth and is a consistently fascinating

and informative listen, even for those, like myself, who

have been following and reading about Clarke's work for

some years. Roth provides some useful background information on his

approach to the role and Clarke's working methods, as

well as a nice selection of anecdotes – unable to drive

at the time of filming, for example, his scenes behind

the wheel were created by a combination of driving doubles

(one of whom had to replace him in mid-shot when he disappears

behind a van) and pulling his car with a rope. He also

pays tribute to Clarke, for whom he was originally also

supposed to do Contact and The

Firm, as well as cameraman Chris

Menges and actor Geoffrey Hutchings ("for me it was

like a proper actor coming in"), who pretty much

steals the film for ten minutes as the centre superintendent.

Amusingly, this being his first film, Roth was under the

impression that all films were shot on Steadicam and was

actually rather startled the first time he encountered

a camera bolted to a tripod. His admiration for a script

that had an intelligent skinhead at its centre is balanced

a little by his own childhood experience of skinheads,

whom he describes as "horrendous people." He

clearly had the time of his life making the film, not

least because of Alan Clarke's sense of humour and relationship

with the cast and crew, and describes the experience as

"One of the best times I ever had as an actor.....I

was in heaven."

The

second commentary track features

Margaret Matheson and writer David Leland. Both provide

excellent background information on the production, which in Leland's case includes his research and thinking behind it.

Leland has plenty to say and does tend to dominate (if

that's the word – he never feels dominant, just

more vocal), though Matheson makes some key contributions

and takes issue with Leland when he complains, with some

bitterness, that Clarke was only seen as a great director after he died. Rarely does the information supplied

here overlap with that on the Roth commentary, and when

it does it sometimes prompts a smile, as with Leland's

certainty that Roth had done some of his own driving in

the banger racing scene, only to later admit that he wasn't

at that particular shoot. Both also pay tribute to Clarke,

Geoffrey Hutchings (who Leland describes as "the

kind of actor every director prays for") and Chris

Menges, for whom this was apparently a "precious

and important" film. Leland's own views on Trevor,

whom he sees very much as a victim of the system, are

also fascinating.

An Archive Interview with Tim Roth is just that, running at four minutes and containing a

few clips from the film, though they are largely brief

and often talked over. Though shot only four years ago

for the Film Four documentary Alan Clarke: His

Own Man, Roth still presents a slightly different

perspective on the film and the character than found in

the commentary, which makes it a valuable inclusion.

Poster

and Stills Gallery has 11 stills (including

a couple that appear to have been scanned in from Richard

Kelly's book on Clarke, or a similar source), 2 DVD covers

and a National Film Theatre programme cover. All are produced

at a decent size and are real production stills, not frame

grabs.

For me Made in Britain is television at

its finest, a film in which script, direction and performance

are in perfect harmony and the audience is constantly challenged

and made to work, but given all the rewards that naturally

accompany first rate drama. It remains one of the finest achievements not just of its brilliant director, but of its equally

talented writer, cameraman and lead actor, which is saying

something when you consider the considerable body of work

that this combination of talent represents. Central to Blue

Underground's Alan Clarke Collection, it

may be equalled by the UK release on picture and sound quality,

but the two very fine commentary tracks make it once again

a one-horse show. Full bloody marks again to a terrific

box set.

|