Note: The reviews here for The Firm and Elephant have been adapted and updated from my earlier DVD reviews of both. Information, technical specs and extra features (save for one, which has also been updated from an earlier review) are all specific to this release.

This stand-alone release will also appear in the Dissent & Disruption: The Complete Alan Clarke at the BBCbox set with the same specifications and extras.

| The Firm: Broadcast Version |

|

The history of the football hooligan goes back to the earliest days of the game itself, the tribal nature of the sport attracting a small hardcore of hardened thugs who, having aligned themselves under a particular, usually local flag, waged war on opposing factions with fist, boot and even knife. The early Roughs and later Bovver Boys were all perceived to have come from a working class background, families living on housing estates in large urban areas. But in the 1980s a new breed of hooligan emerged, one more organised and even more tribal in nature. These were not impoverished working-class lads searching for an identity in a world out of their control, but affluent young men in well so-called respectable jobs. They were the product of Margaret Thatcher's skewed vision of Britain, where collective action was demonised and good and bad citizens alike were encouraged to think of themselves first and get rich any way they could, irrespective of the cost to those around them or society in general. From this grew a mouthy and obnoxious entrepreneurial class and a new breed of hooligan. Using football as a banner under which to unite, they formed organised gangs that would not just fight on their home turf, but actively hunt out opposing groups and take them on. This was organised war, a new kind of thuggery for a new breed of middle class. In a direct reference to the rampant capitalism from which they were born, these gangs were known as Firms.

By the time he came to make The Firm, Alan Clarke had long since established himself as one of the innovative and boldly exciting directors in British television drama. His TV play Scum had caused a ruckus at the BBC and been promptly banned by the very corporation that commissioned it in the first place. His response was to re-shoot the whole film on 35mm and release it as a cinema feature instead. The result attracted both praise for its energy, honest directness and committed performances, and criticism from self-appointed moral guardians and governmental types, who were appalled that a film would seek to expose what too many were unaware was going on in British borstals of the day. Made in Britain teamed Clarke with the equally adventurous David Leland, but as Leland moved into the director's chair for more mainstream projects such as The Land Girls and Band of Brothers, Clarke's work became increasingly confrontational and experimental, reaching its peak with his 'walking films', which included Road, Christine and the brilliant Elephant, the last of which is included in this Blu-ray release. The Firm was to be Clarke's final film (he died of cancer just two years later), made when knowledge of this new class of hooligan was nowhere near as widespread as it subsequently became, and grew in part from the director's own anger at the people he felt were ruining a game that he loved.

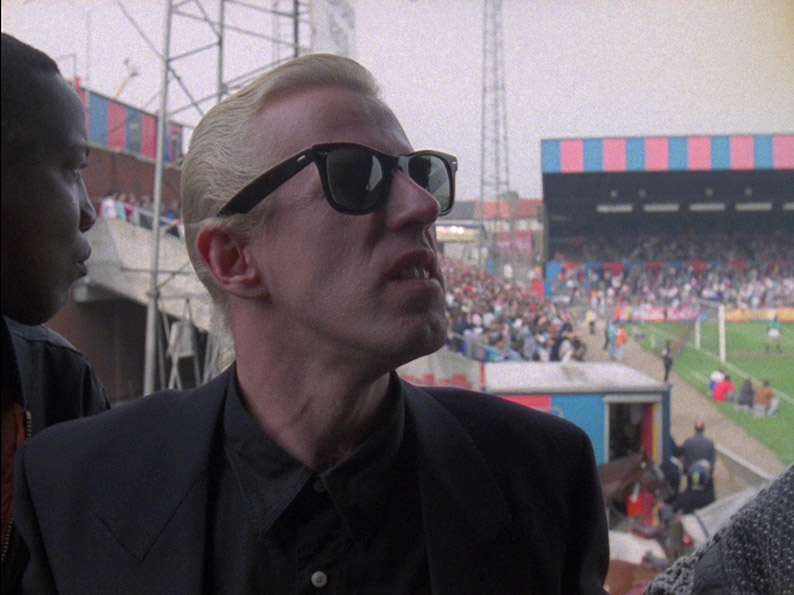

Clive 'Bex' Bissell is a successful young estate agent who lives in a London suburb with his wife Sue and their infant son Sammy. He is also the head of a local firm, the Inter-City Crew (or ICC, based on the West Ham Inter-City Firm, some of whom acted as consultants on the film), whose principal rivals are The Buccaneers led by the albino Yeti and a Birmingham-based crew captained by the hard-nosed Oboe. Bex has ambitions to lead a united firm into Europe and calls a meeting to propose the idea to the rival gangs. Inevitably, they pour scorn on his suggestion, but tell him that if the ICC can fight each of their gangs on their home turf and beat them, then they will fall in line and follow him to Europe.

From the opening Steadicam shots framed on Bex's head and cocksure stride, Clarke establishes that this is to be less a film about the ICC than its enigmatic leader, and he scores his first gold in the casting of a young Gary Oldman, who brings a sometimes ferocious energy to an unlikeable but still utterly compelling central character. Bex is a symbol for the self-centred, destructive element that was so much a product of 1980s Britain, all outward respectability – the nice house, the family, the decent car – under which lurks a barely controlled monster. He fights not for his family or friends or any real cause of note, but because he "needs the buzz." Neither hard drink not drugs are part of Bex's make-up, providing no get-out clause for his behaviour – his addiction lies purely in the thrill of inflicting violence on others.

Bex certainly has some serious issues, and his fragile self-image is both his driving motivation and his Achilles heel. After directly challenging Yeti and Oboe, he cheerfully pops round to his parents' house, where his old bedroom remains a shrine to his childhood and a holding cell for the weapons of his trade. Having reacted with resolute calm to the earlier defacement of his car by the Buccaneers, it is here we first glimpse the tormented creature that simmers beneath, as he carefully arranges a pillow that he then repeatedly and angrily clubs, furiously yelling the names of his hated rivals as the blows rain down. Later, when things aren't going so well and one of the gang talks about leaving, Bex turns on him in a sudden burst of controlled fury that instantly brings him into line – their final mission may seem suicidal, but it is still preferable to having Bex as an enemy.

By then the ICC firm is starting to fall apart. Having suffered serious defeat at the hands of Oboe's ambush and Yeti's hit-and-run tactics, there seems to be nowhere for them to go, but in a brutal final fight the monster inside Bex is finally unleashed, most graphically realised in the animalistic scream he lets rip after beating an opponent to within an inch of his life. And Oldman sells every aspect of this character as real – the cocky estate agent, the jokey but still devoted Dad ("Shall we tell mummy to piss off?"), the put-upon husband, the ambitious would-be leader, the threatening soldier and the out-of-control monster – and the transition from one to another is always convincing. His relationship with his wife (impressively played by his then real-life wife Lesley Manville) in particular is most realistically handled, from the saucy small-talk to the screaming rows – the dialogue and delivery here are always just right.

As usual with Clarke, pretty much all of the performances are absolutely spot on. Phil Davis, in a role originally offered to Tim Roth (can you imagine?), plays Yeti with a winning combination of icy cool and sneering superiority, and Andrew Wilde makes for an effectively intimidating Oboe. The soldiers in the firms themselves are also played with energy and commitment, even if a couple of them really don't look like they could hold their own in a serious fight. And I'll freely admit now that when I first saw the film I suspected that the mixed racial make-up of the firms was less a reflection of reality than a ploy on the part Clarke and screenwriter Al Ashton to focus our attention on the tribal element of this particular breed of affluent thug, but subsequent research revealed that it was an accurate reflection of the racial mix in the ICF, on which the ICC was based.

Everything feels just right here – I grew up knowing these people and recognise almost every one of them as real. The detail in Ashton's script and Clarke's handling is consistently bang-on, notably in dialogue that always feels authentic to the place and time, even in off-hand moments ("You wanna T-Cut that," Bex's dad advises on seeing his son's defaced motor, to which Bex replies "I don't believe you sometimes – needs a new skin, that does"). This even extends to the clothing (these guys liked to look good) and their choice of cars, particular favourites being sporty, soft-top Ford Escorts and performance BMWs, still a wankers' favourite in my neck of the woods. The Buccaneers' targeting of these vehicular status-symbols appropriately ties the activities of the firms to the capitalistic aspirations and lifestyles of their members. Indeed, when the Buccaneers demolish the Hornchurch Boys' BMW in a brilliantly edited series of lightning cuts, for the vehicle's owner its's the final straw and the end of his association with Bexy's firm – he will take an assault to his body, but not to his treasured possessions. Elsewhere there are nicely low-key references to Bex's financial status in his casual insistence on first class tickets for the trip to Birmingham and his jovial "Well if you've got it..." response to his Dad's suggestion that he is just throwing money away by having his car resprayed. All of this prefigures the present day hijacking of what was originally a working class game by those with the money to buy insanely expensive season tickets, a new club strip for their kids every few months, and even a seat in the company box, where they are protected from the horrors of weather and ordinary people, and where the game itself becomes a distant background entertainment.

Clarke's direction is superb throughout, his handling of the actors matched at every turn by his sometimes electrifying command of the film medium. Shot entirely on Steadicam, the film is peppered with drifting, gracefully circular camera moves and long tracks of Bex as he strides ever-purposefully down roads or corridors. Clarke holds these shots for longer than most other directors would and the effect, as in all of his 'walking movies', is to connect us completely to his central character, forcing us to watch him in almost anthropological detail as he marshals his forces and attempts to keep that monster inside in check. These long takes give way to faster cutting in more action-driven scenes, and the use of urgent editing and grabbed shots in the fights, combined with the committed physicality of the actors, creates a real sense of the viciousness of these conflicts without overpowering the audience with graphic detail.

On its first TV showing the violence was, inevitably, a controversial issue, but it is central to the story and thus an essential component. The pitched battles in particular are handled with brutal realism, the furious chaos of an all-out rumble caught with documentary authenticity, despite being meticulously choreographed in advance. If Clarke holds back from showing us the most horrifying assault – which I always believed was a double nostril splitting but is actually far worse (see The Director's Cut below) – its suggestive nastiness still hits home. It is somehow appropriate that the very same knife used here is also at the centre of the film's most genuinely horrifying moment, when a distracted Bex fails to realise that his child has picked up the weapon and is using it as a toothbrush. This sequence powerfully calls into question Bex's sense of responsibility and his priorities regarding his family, as well showing most graphically how his addiction to violence will eventually destroy everything he holds dear.

The film climaxes in two compelling Steadicam tracks and a particularly vicious fight, whose conclusion is tragic but somehow inevitable, given the escalating nature of the violence between the warring gangs. But the final five minutes are the film's real coup-de-grace, a largely improvised scene in which the newly united firms passionately justify their way of life to a television documentary crew. As the interview progresses, emotions run high and the interviewers lose control of the situation, and talking gives way to shouting, beer is thrown at the camera and arguments mutate into ritualistic and nationalist chanting. Suddenly even the weakest-seeming member of this new unified firm seems genuinely threatening, and as a combined force they seem frighteningly unstoppable. It is Hornchurch boy Billy (played by a young Steve McFadden, later to make is mark on TV as hard man Phil Mitchell in Eastenders) who leaves us with this scene's most sobering message: "If they stop it at football, we'll go to boxing, we'll go to snooker, we'll go to darts..." Brilliant, compelling, chilling television.

As you'll hear discussed a number of times on this disc, The Firm ran into trouble with the powers that be and other sundry rabble pretty much from the moment it was completed. The BBC hierarchy was disturbed by the content, and the usual right-wing toadies – The Sun, TV watchdogs, a publicity-seeking Tory MP – were calling for it to be banned before any of them had even seen it. Eventually, reluctantly, Clarke agreed to make the cuts required to secure the film its TV screening, which eventually took place some months after its completion.

The new Director's cut included on this disc restores the film to its original edit, and has been meticulously reconstructed by inserting the previously deleted material from Clarke's personal work print into the restored broadcast version. The work print is inevitably of considerably lower quality than the restoration and the previously cut material thus does tend to stand out a mile, but this does make it easier to identify where the cuts were made, at least for those who have not committed almost every shot in the film to memory.

It should be noted that there are a couple of surprises here, and that any discussion of them is inevitably going to deliver some serious spoilers for those who are new to the film. If that includes you then I'd hop forward to the next section or grab a copy of the film and watch that first.

Perhaps inevitably, many of the censored shots involve physical violence. In the case of the climactic pub fight this appears to be down more to the number of blows delivered rather than their ferocity or extremity, but the wide shot of Oboe cutting Yusef's face in the Birmingam brawl now includes a more graphic close-up. But there is one sequence where the enforced cuts (no grim pun intended) really did change my perception of what I thought I was seeing, which in turn impacts on how you view the lead character. The scene in question is the one where Bex ambushes and assaults Oboe as he arrives home. In the broadcast version, Bex pins Oboe to the floor, waves a Stanley knife in his face, and the film then switches to a wide shot, the action viewed distantly from outside the house, and we witness (unclearly) what I have always assumed was a double nostril splitting. With the censored footage restored we can clearly see that what Bex actually does is vertically slash both of Oboe's eyeballs (a later verbal reference to this assault was also removed from the broadcast version). A horrible scene in itself – Oboe's screams are so much more traumatic in this version – it also impacts on how we view Bex from this point on and the extremes he is prepared to go to in his machismo-driven pursuit of vengeance. This in turn heightens our anticipation about just what he might be preparing to unleash on Yeti in the final pub battle.

Surprisingly, perhaps, not all of the cuts were violence related. Gary Oldman and Leslie Manville's unembarrassed familiarity with each other (they were married at the time and Manville was pregnant with their son) meant that they were comfortable pushing the sexual content a little beyond the television norm. In the early living room snog, the film does not cut to mid-shot as it does in the broadcast version, and in the now unbroken wide shot we can clearly see Sue with her hand firmly on Bex's groin. The scene also runs for longer than it did before and includes a few more seconds of suggestive horseplay at the end.

But the sequence that clearly gave the BBC the heebie-jeebies is one where Bex comes home late, gets into a barney with Sue and ends up forcing himself on her in what quickly descends into aggressive rape. It's an extremely uncomfortable scene to watch, but at its worst moment what we think we are watching is brilliantly undercut when Sue starts laughing and the whole thing stutters to a halt as a result, and it quickly becomes clear that this is all play-acting and that this is how these two get their rocks off. It's a scene whose existence you'd have already been aware of if you have 2entertain's 2007 DVD release, where it was discussed by Leslie Manville on the commentary track (which is also included here). A few occurrences of the word 'fuck' were also trimmed to meet an arbitrarily defined BBC quota on its use.

It starts like this. An unidentified man purposefully crosses a road and enters a public swimming pool building, which at first glance appears to be empty. On reaching the pool itself, he circles its perimeter, checking changing cubicles as he goes. Is he looking for someone or checking for something? We don't know at this stage. He then heads back the way he came, but instead of leaving the building he takes a right turn and walks down a corridor. About halfway down he stops and turns, pulls out a shotgun and coldly kills a cleaner. He then tucks the gun into his coat and leaves. His pace does not change, he does not break into a run. The camera then returns to the body of the murdered man and lingers on it for considerably longer than would be normal for a crime or action movie.

To those coming completely fresh to Alan Clarke's penultimate film, Elephant, this must seem an intriguing set-up to a story in which the explanation for what just happened will later become clear. In this respect it recalls the opening of John MacKenzie's The Long Good Friday, whose prologue was also set in Northern Ireland and which also featured an assassination whose narrative purpose at that point in the drama was a mystery (one not clarified until much later in the story). Like the start of MacKenzie's film, there is no explanatory dialogue, but unlike that film there is no music either and the camera placement and cutting are also a little left-field, the use of wide shots and drifting Steadicam giving it a coldly observational feel. Only when the shooting takes place do we move in closer to the assassin, and even then it is the gun that becomes the focus for the camera's attention, not the man who wields it. Facial close-ups are fleeting here, and we are not asked to identify with either the gunman or his victim, merely to watch the terrible act that unfolds before our eyes. Even so, at this early stage we still feel on reasonably safe narrative ground.

But then scene two kicks off. The camera patiently observes a petrol station shop from the far side of the road. A car pulls up and a man gets out, enters the shop and calmly shoots the counter clerk. The gunman drives off unhurriedly – he even waits for a break in the traffic before pulling out – and the camera once again settles on the body of his victim, which it unwaveringly observes for close to twenty uncomfortably long seconds. Again the approach is coldly observational, emphasised by a complete lack of dialogue or music. By now most viewers would be starting to wonder. Are the two killings related? Is a more complex story unfolding?

Scene three brings more of the same. In a single Steadicam shot, another unidentified man walks down an alleyway, and as he turns a corner a second man suddenly appears and shoots him. As the victim lies on the floor, the camera circles his body, into which further bullets are fired. His job complete, the killer pockets the gun and walks away, heading off in a reverse walk of the route that delivered his victim to him.

By now few will be under the impression that they are watching a standard drama. By the fifth or sixth killing the tone of the entire film has been set and the audience divisions will have set in, splitting those who are prepared to go where Clarke is taking them from those who are not. There is no plot, almost no dialogue and no musical score, just a series of eighteen sectarian assassinations, one after the other, with no on-screen reasons given, no conclusions attempted and no characters shaped in any traditional sense. No-one is even identified by name. This is minimalist film-making at its most starkly pure and is bound to alienate a sizeable, dare I say more traditionalist (not to mention sensitive) portion of any potential audience. But stay the course and you will experience a work whose single-minded sense of purpose, stark rejection of traditional storytelling techniques and astonishing technical confidence mark it as one of the boldest and most important films ever to be screened on British television.

The project was originally the brainchild of one Danny Boyle, later a director of some note himself (do we really need to mention Trainspotting, 28 Days Later and Slumdog Millionaire? No, I thought not). Having landed a producer's job at BBC Northern Ireland, he became aware that many of the shootings taking place in the province were going unreported on the mainland, presumably because they involved ordinary citizens rather than politicians or others the British press deemed somehow newsworthy. He was also a huge fan of Alan Clarke, and having written to him and been invited onto the set of Clarke's previous 'walking movie' Christine (1987), he hired him with this very project in mind and the two worked together to develop the film to its present form. The decision to film on the streets of Belfast was a brave one given that the locals were living the reality of sectarian violence on a daily basis, but this not only adds to the film's documentary-like authenticity, it also provides some arresting locations – strangely empty streets, red brick industrial and municipal buildings and vast but deserted factories, all depressingly vacant symbols of Thatcherite industrial policy. The enigmatic title, meanwhile, was inspired by Irish writer Bernard MacLaverty, who described The Troubles as akin to having an elephant in your living room – it is so enormous that no-one can ignore it and it gets in the way of everything you try to do, and yet after a while no-one talks about it any more and you learn to live with its presence.

A work whose content consists solely of a series of killings may seem a daunting prospect, but Clarke's camera style and editing structure makes it impossible to tear your eyes from the screen. As people walk, John Ward's mesmerisingly fluent wide-angle Steadicam goes with them, involving us in an intimately complicit way with what subsequently unfolds. And with no character set-up and no expository dialogue, we can never be sure just who we are watching. Is this a gunman on his way to kill, as in the opening scene, or a victim unknowingly walking to his own death? As the film progresses, the process of pre-identification does not become any easier. In one memorable scene, a man walks onto a local football field and the presumption is that he is there to kill one of the players, but we are wrong-footed when he casually joins in a kick-about – when the attack does come it proves genuinely startling. Later, two men purposefully walk a considerable distance to what we assume will be the killing of a third person, but we are again being misdirected and the truth delivers a horrifying jolt.

All of which may make Elephant sound like it is creating grisly entertainment out of a serious issue, which could not be further from the truth. The killings are in no way glamorised and are observed with a matter-of-fact detachment that proves increasingly chilling. The sequential game-playing with identification of killer and victim also has purpose, reminding us repeatedly that in this situation just about anyone can be a killer – they don't wear horror masks or deformed leers to announce their presence – just as anyone can also become a victim. There are also no specific killing grounds and death can strike from anywhere, on a street, in a back alley, in a restaurant, at work, or even on your own home. We are never shielded from the effects of the murders, the camera repeatedly settling on the bodies of the victims in a way that is most appropriately disturbing. You can almost feel Clarke's hands on your head, pointing you towards them and saying, "Look. Look at what happens. Look at the result of all this bloody killing."

Individual sequences are both astonishing in their handling and horrifying in their cold viciousness, and the cumulative effect is genuinely devastating. But Elephant is not a film of separate scenes but the absolute sum of its parts – it has to be seen as a complete work, in one uninterrupted sitting. Even today, in times of peace accords and regional assemblies and open communication in Northern Ireland, it has the power to stun an audience to silence. Clarke has been widely acclaimed as one of Britain's greatest directors, but Elephant strongly suggests that he was touched by genius.

It is, I sometimes find, a little too easy to forget just how good a medium 16mm film can be. This memory lapse, at least for my generation, stems in part from its past use on British television for exterior shots in otherwise shot-on-video, studio-set dramas and even comedies (Monty Python once built a wonderful sketch around this visual mismatch of film and video). In the transfer to tape, these film sequences tended to end up looking softer, grubbier and less well defined than the video that surrounded them, whereas in their raw projected state they probably looked considerably nicer. Both The Firm and Elephant were shot on 16mm on what I'm guessing was high speed stock – both include material shot in low light and Clarke's fondness for being able to point his camera in any direction must have restricted just how much light his cameramen could throw on some scenes. I made allowances for this when I reviewed the previous Second Sight and Blue Underground DVD releases, but after watching the transfers here I've been forced to rethink my assumptions. Both of the films have been remastered here, I'm guessing from the original 16mm negatives (I'll confirm this one way or another when I get my hands on the literature that comes with the Dissent & Disruption set). The results, for two films shot on 16mm, partially in low or available light, are spectacular. What strikes you up front is how consistently crisp and detailed the image is, at its eye-catching best on daylight exteriors but still holding its own when the light levels drop and far surpassing any previous DVD release of either title. The balance of the contrast range is pretty much perfect, with rock solid black levels, strong shadow detail and no white burn-outs – a couple of sequences in Elephant have a very slightly over-exposed feel in places, but that was always present and no picture detail is lost. The colour palette has that warm, slightly pastel-leaning feel that I always associate with 16mm film stock, and the image on both films is spotless and free of any trace of damage. So crisp is the picture now that a very fine hair that was caught in the gate for the filming of one interior shot in The Firm is now visible for the first time – most won't even spot it, and it's too small to act as even a minor distraction. There also appears to be a small hint of discolouration in the top-right corner of frame in The Firm, but again this will likely go largely unnoticed. A fine film grain is still visible on both transfers, but has not been emphasised or flattened with DNR. A superb job all round – the screen grabs here really don't do either justice.

Both films feature Linear PCM 2.0 mono soundtracks that I'm assuming have also been restored, at least if the clarity of dialogue and sound effects and lack of background hiss and damage here are anything to go by. There's not much in the way of bass response, which is hardly surprising for non-Dolby surround TV productions from 1989, but in all other respects both tracks are in fine shape. The soundtrack of The Firm in particular is very clear and vibrantly mixed. The more deliberately low-key Elephant still captures environmental sounds crisply and delivers the required jolts on the explosive gunshots.

Optional English subtitles for the deaf and hearing impaired are available on both films, but Elephant doesn't need them or indeed make much use of them.

Gary Oldman commentary for The Firm: Director's Cut

In a screen-specific commentary recorded specifically for this disc, leading man Gary Oldman looks back at his experience making The Firm. He's full of praise for his fellow performers, all of whose names are still fresh in his memory no matter how small their role, and there are a fair few anecdotes about them and the filming itself, some of which you'll not find recounted elsewhere on this disc. He remembers the argument scenes with his then wife Leslie Manville as being fun to do, and landing a few bruises in the fight sequences despite their careful choreography. There is, as you would hope, a good deal on Alan Clarke, including his working methods, his collaborative approach, his economical use of Steadicam 'walking shots', and the fact that he was such a joy to work with and always receptive to ideas from others. There are a few sizeable dead spots here, but when Oldman does speak he's always worth hearing, and he pays a moving tribute to Clarke as the film draws to a close.

David Leland Introduction for The Firm: Broadcast Version (2:25)

An introduction to the film by Made in Britain writer David Leland for its screening as part of season of his films screened on the BBC a few years back (I wish I could remember the year but I can't). This also includes a choice extract from an interview with Clarke that you'll find elsewhere on this disc.

Leslie Manville, Phil Davis, David Rolinson and Dick Fiddy commentary for The Firm: Broadcast Version

Ported over from the 2007 2Entertain DVD Special Edition DVD release of the film, this commentary features actors Leslie Manville (Sue) and Phil Davis (Yeti), BFI archivist Dick Fiddy and David Rolinson, author of a book on Alan Clarke published in 2005. What unfolds is a most engaging mix of memories of the shoot from the actors and analysis of themes and individual scenes from Rolinson, while Fiddy acts as compere and does a stout job of prompting his fellow contributors, as well as throwing in a fair few observations and facts of his own. And there's a wealth of interesting material here. Manville talks about the censored violent sex-play sequence, the BBC insisting they reduce the number of uses of the word 'fuck' from something like 8 to 7, outlines how the kid-with-the-knife scene was filmed and why it wasn't easier doing intimate scenes with her husband – "I don't have any trouble getting my kit off," she reveals. Davis looks at elements that are common to The Firm and his own differently slanted football hooliganism film I.D., recalls having his hair bleached ("I looked like Jimmy Saville") and Clarke's refusal to meet the people on whom the characters were based. There's also general discussion on a number of topics, including the notion of specifically Thatcherite hooligans, the influence of the West Ham Inter-City Firm, the fact that at no time in the film to we actually see a football, and a good deal more.

Commentary by Danny Boyle and Mark Kermode on Elephant

An extra feature lifted from Blue Underground's 2004 Alan Clarke Collection and a terrific one that I'm delighted to see included here. Most effectively prompted by critic Mark Kermode, the film's producer, Danny Boyle, supplies a wealth of information on the background and the shooting of the film, as well as his own memories of working with a man he still regards as the one of the greatest of all directors, and is most self-effacing about his own work by comparison. The commentary is at first not screen specific but in the later stages the two men increasingly discuss individual sequences as they play out, going into some detail on the use of locations and the level of accuracy in certain scenes. Boyle also reveals that Gus Vant Sant specifically asked him if he could use the title for his own film of the same name, a work who style, structure and key sequences were clearly influenced by Clarke's original.

Alan Clarke Interview (1989) (10:05)

Actually compiled from three separate interviews and fleshed out with extracts from the films under discussion, Clarke talks about his intentions and approach on Elephant, the importance of portraying violence as honestly and graphically as possible, the fact that the activities of the gangs in The Firm have nothing to do with football and has everything to do with their stupid macho behaviour, and the frustration of finishing a film that you are happy with and hope the public will connect with, only to have someone from BBC management then step on it.

Open Air: Elephant Discussion (1989) (21:00)

Two sizeable extracts from one of those points-of-view programmes I admittedly used to watch and fume my way angrily through, in which Outraged of Bournemouth would write or phone in to complain about (or sometimes praise) the previous night's or week's television. The programme under discussion here is Elephant, which according to the slightly snooty presenter (who outrageously attempts to dismiss the film as 'tedious') prompted such a flood of complaints they had to really work hard to find a letter with anything nice to say about the film. In the first half, Alan Clarke fields a couple of angry complaints and one of praise by phone from Los Angeles, and a young and most eloquent Danny Boyle does likewise in person in the second. Not all of the complaints are without a degree of foundation, but those praising the film make a more persuasive case. Then again, I'm biased.

Alan Clarke: Out of His Own Light [Part 12] (36:20)

The upcoming BFI box set Dissent & Disruption: The Complete Alan Clarke at the BBC includes a wonderfully detailed documentary on Clarke's BBC work that is spread over 12 discs and divided into episodes that focus primarily on the films contained on the disc in question. I'll get into the documentary as a whole when we review the box set itself, but Part 12 is focussed exclusively on Elephant and The Firm, and has so many interviewees that I stopped jotting down their names before the halfway mark. Key contributors include master cameraman and Steadicam operator John Ward, Richard Kelly, editor of the excellent 1998 book Alan Clarke, The Firm actors Leslie Manville, Phil Davis, Jay Simpson and Gary Oldman (an archive interview whose 4:3 framing has been retained and not cropped to fit the 16:9 aspect ratio – thank you), and a whole load more, including actor Brian Cox and director Paul Greengrass, both devoted fans of Clarke's work. It's an excellent, information-packed and anecdote-crammed piece that seriously bodes well for the 11 parts that precede it (I've only watched a couple so far), even if a few of the interviews fall victim to shifting sunlight that pushes their subjects into shadow. Like I care – its what they have to say not what they look like that counts here.Stephen Frears' opening comment about Clarke is a peach: "He was very pure and very uncompromising, and sort of became purer and more abstract as he got older, whereas the rest of us grew fat and corrupt and headed for the money."

If you have any doubt that Dissent & Disruption: The Complete Alan Clarke at the BBC is going to be the box set of the year then this brilliant, beautifully produced taster – which has effectively been lifted from the set unaltered – should confirm it beyond all doubt. For those uncertain about coughing up for the full Dissent & Disruption set but keen to get their hands on two of Alan Clarke's very finest works, I cannot recommend this release highly enough. The transfers are superb and the extra features aregenerous in quantity and first-rate in quality. A brilliant and inspiring Blu-ray release.

|