|

As 1979 began I was in my second year of film school. There was a generous sprinkling of cinemas in the immediate area, to which I made at least three visits each week. The local arts centre was where you went to see the older classics or the more recent foreign language releases, while the mainstream and more successful American independent titles could be caught at one of three very large screens within walking distance of the college. Many of these films were decent enough but unremarkable, but just occasionally were extraordinary enough to convince you that by attending the first week of their release you were part of cinema history. What rarely played in either location were British movies, and those that did tended to be set in past times and tell stories about the privileged classes, not the sort of people that a young rapscallion like myself had much in common with. This was the one thing I felt was missing from my cinema visits of the day, films that reflected my own life, had characters that spoke as I did, that took place in believable settings and had stories that felt as if they were drawn from what I recognised as real life. Where were the British realist films that had seemed so crucial during the sixties, from Jack Clayton's Room at the Top (1959) through to Ken Loach's seminal Kes (1969)? Even Loach had fallen into the cinematic wilderness at this point in his career and was working only sporadically in TV. So my hopes were high when I queued up to buy my ticket for Scum. I knew little about it and had been attracted primarily by the image of a ferocious-looking young man waving a length of piping that adorned the poster, on which the title of the film was sprayed as a crude splash of graffiti. I emerged from the cinema buzzing with excitement at what I had just seen. After close to a year of mainstream Hollywood products, this was a thumping great kick in the bollocks, a brutal, confrontational and uncompromising but brilliantly written, directed and acted work with a social message that really resonated with me. It seems ironic in retrospect that this cinema feature was my introduction to the work of Alan Clarke, a now rightly revered filmmaker who worked primarily in television.

For those unfamiliar with the film, Scum takes place entirely in a in a borstal, a word that will probably mean little to younger viewers or readers who were born outside of the UK, particularly as the borstal system was abolished by The Criminal Justice Act in 1982, just three years after the release of this film. Coincidence? That's not for me to say. Borstals were institutions in which young offenders were incarcerated under a strict regime of harsh discipline, work and education that was intended to teach them respect for authority, install a strong work ethic and build character. At least that was the theory. By the 1970s, however, it was becoming clear that in a significant number of these institutions, control was being maintained by a regime of violence, bullying and racism dished out by staff and inmates alike.

As the film begins, three new inmates are being transported to just such an establishment. Tough, street-wise Carlin (Ray Winstone) has been transferred from another borstal after hitting a warder, quiet and introverted Davis (Julian Firth) ran away from a minimum security establishment, and black newcomer Angel (Alrick Riley) is a first-time offender who is unprepared for the racial abuse he will be subjected to by the white custodians and inmates of his new home. Carlin in particular becomes an immediate focus for attention, his reputation as a 'daddy' – an inmate in an unofficial position of power attained and maintained through a combination of violence and gangland-style intimidation – having arrived ahead of him, which brings him into immediate conflict with the warders and the incumbent daddy, Pongo Banks (John Blundell).

Despite theoretically being less deserving of our sympathies than the vulnerable Davis or the racially abused Angel, Clarke and Minton make sure we register from the off that Carlin is our boy. It's his face on which the film opens and it's with him that we spend the most time during the course of the first half-hour of scene-setting. It's a shrewd move, one that repeatedly plays on our building expectation that he will kick against the bullying he suffers in pursuit of a quiet life, particularly from Banks and his two mouthy cohorts, Richards (Phil Daniels) and Eckersley (Ray Burdis), with whom he shares a small dorm and who make their mark early on by beating him senseless. The warders also have it in for Carlin because of the self-defensive blow he landed on a warder at his previous establishment. It's doubtless they who ensured that Carlin would be placed in a dorm with Banks and his crew, knowing that the incumbent daddy would make a point of putting this former daddy firmly in his place. The savvy and experienced Carlin is certainly aware for the trouble he may face and is meticulous in his well-practiced responses to barked orders from hostile wardens. Yet we know from his demeanour, the looks he throws others and his moments of barely suppressed fury that sooner or later this reluctant worm will turn. When he does so the effect is electrifying, a cathartic explosion of violence and aggression that definitively changes the power structure of this wing of the borstal.

Scum was the first film directed by Clarke for cinema release and would not have existed at all had he and writer Roy Minton not been shafted by a regime change at the BBC. The film was originally commissioned as entry in the channel's prestigious Play for Today series by BBC1 controller Brian Cowgill, and was completed and scheduled for screening when things went tits-up. During the course of the production, Cowgill departed and was replaced by the more cautiously minded Billy Cotton. Cuts were requested, Home Office and prison officials were asked to view the film and the decision was ultimately made not to transmit it. It was to be another 14 years before this version was to receive a single TV screening, and even then it was on the rival commercial station Channel 4, introduced by Made in Britain writer David Leland (who memorably instructed us all to set our video recorders going) as part of a season of programmes paying tribute to Alan Clarke, who had died a year earlier. The exact timeline of events that led to Clarke being approached to remake it for the cinema seems to vary depending on who you talk to (see the many interviews in this disc's special features), but remake it he did, and the result was one of the finest British films not just of 1979, but of the 1970s and well beyond.

Events play out much as they do in the TV original and many of the key cast members from that version repeat their roles here. There are, however, some notable changes to the cast and the content. The most obvious of the latter is the stronger language, which some have seen as part of the process of sensationalising the story for the wider cinema audience. I couldn't disagree more. In the original, racial abuse is used as a method of verbal bullying by guards and inmates alike and the swearing is a logical and non-racial extension of that – had the TV play been made ten years later when restrictions on language had been eased for British television, then I have absolutely no doubt that this is how the script would have played from the start. Indeed, given that the film is based on real-world institutions in which bullying, intimidation and violence were standard operational procedure, the very idea that such language would not be used as part of that is patently absurd, and its inclusion here contributes to both the realism and the menace of the threats, and is a key component of many of the film's most quoted lines. Carlin's confrontation with rival black daddy Baldy (Peter Francis), for instance, is transformed by just one word: "Where's your tool?" Carlin asks his rival. "What fucking tool?" the bemused Baldy responds. Wallop. "THIS FUCKING TOOL!" Now that is intimidation.

A solid case has been made by others about why the rawness of the original TV play gives it the edge over the more rehearsed movie remake, and I absolutely get that. Clarke's observational shooting style and the more restrained performances give the earlier version a more documentary feel, which itself would have made it troubling viewing if seen on TV in 1977, had the tasteless twerps in charge not banned it, of course. Having said that, giving a now more experienced cast of young actors the chance to repeat roles with which they would have been familiar brings its own benefits in the increased confidence and assurance with which they are played. This is especially true of Ray Winstone's extraordinary performance as Carlin – where his more low-key delivery worked perfectly for the documentary feel of the TV play, his burning and sometimes ferocious anger here propels the story forward like a bulldozer on steroids. Nowhere is this more evident than the sequence in which he confronts and defeats incumbent daddy Banks and his cronies. Even in the original this was an highly charged and impeccably timed scene, but here Winstone's calm tooling-up at the snooker table ("Yeah, well, carry on"), the vicious physical beatings he dishes out to Banks and the cocksure Richards, and his furiously delivered pronouncement to the downed and bloodied Banks, "I'm the daddy now! Next time I'll fucking kill you!" leaves you and them in no doubt that from this point on Carlin is in charge and that it's going to take a considerable force to dislodge him. The staff, of course, have the power to do just that, but having been daddy at his previous borstal Carlin knows how to play the system, just as the system is all too aware that if it is going to maintain its current level of control over the inmates, it is going to have to recognise his new position of power and negotiate directly with him. This doesn't sit comfortably with everyone, of course. Immediately following Carlin's defeat of Banks, he first-half nemesis, warder Sands (John Judd), dishes out a telling warning: "I'm having you, lad. You banged that officer at Rowley. You must be thinking you've walked quietly away from that one. But here's here. He's me. He's every fucking screw in this borstal, every one of us." Yet even he is aware by this point that there's been a shift in power and that his boy Banks is no longer top dog, something beautifully captured by Judd as he turns away from Carlin and his expression and body language shift from cocksure anger to frustrated defeat, and Carlin has to fight not to break out into a triumphant smile.

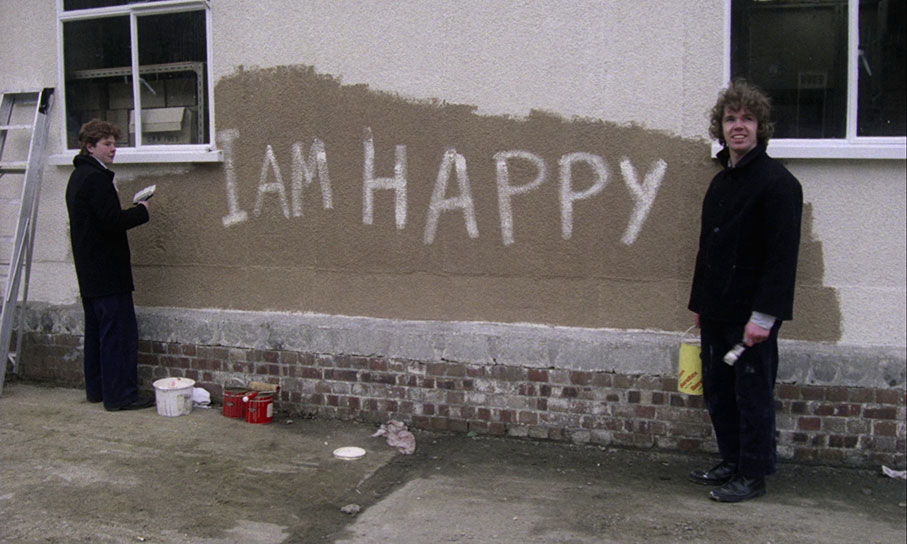

As in the TV original, the flipside of Carlin's no-nonsense brutality is Archer, an intellectual misfit in this environment who is determined to cause as much trouble for the system as he can using methods that his custodians, notably the overtly religious governor, have no previous experience of dealing with and do not know how to effectively respond to. In the original, Archer was played by David Threlfall, but his contract with the Royal Shakespeare Company forced a re-casting for the film, and here Clarke struck gold with the talented Mick Ford, a young actor relatively new to film and TV (his only previous film role was in Jack Gold's The Sailor's Return the previous year) who works such wonders with the role that he almost steals the film from Winstone. His cocksure gameplaying with the routines imposed on the inmates is both hilarious and inspiring, a smart and non-violent fuck-you to a system that only knows how to respond with aggression to any deviation from its rigidly imposed norm. Archer is a man of principle, a dedicated protestor prepared to suffer for his cause (his vegetarianist refusal to wear leather boots means he has to walk and work outside in the snow in bare feet), but whose non-conformity has become for him a way of staving off the punishing consequences of boredom. Almost every time he makes an appearance you can be sure that he'll do something to put a smile on your face, whether it be the comically mannered delivery of his name and number, the drawn-out pronunciation of the word "Trust" when baiting the Matron during a discussion period, or the painting of the words "I am happy" on a wall he is supposed to be decorating. He's also in the film's most telling scene, when he sits down with warder Duke (Bill Dean) and attempts to explain to him why warders are as much prisoners of the system as the inmates, honesty that infuriates Duke and lands Archer in further trouble. Ford's interpretation of the role differs substantially from Threlfall's, enough, indeed, for them both to be enjoyed and appreciated for differing reasons. Threlfall's is certainly more restrained and a little more grounded in reality, and my preference for Ford's stems in part from the fact that I saw and fell in love with his interpretation several years before I got the chance to see the original film, but also because there are times when his take on Archer reminds me of me, or at least a version of me that exists primarily in my own head, one that has Archer's nerve, determination, self-control and natural cool. It's a view echoed by Ford himself on the special features when he says, "I would have loved to have been Archer and I know I wouldn't have been, because the balls required to do that, to survive against the system and against the boys, is something I could never do."

The supporting cast are as impressive as they were in the original, the one notable improvement being Richard Butler's delicious turn as prison Governor Baildon, replacing the original's Peter Powell and clearly relishing the lines given to him by Minton. His delivery infuses almost every word with an extraordinary degree of self-righteous judgment and transforms even the straightforward into something memorable. Just listen to how he says the single word "Indeed" when confronted with Archer, a word that simply slips by in the original. And who amongst those familiar with the film will not smile at the tone of voice he adopts to greet Archer's entry (Ah, Archer...") into his office or his explosive retort of "We'll have no more talk of MECCA!" to Archer's calculated attempt to enrage this devoutly Christian man by claiming to be drawn to the Muslim faith.

Matching the increased confidence of the actors is Clarke's more animated direction, which quietly showcases a style that would shape much of his subsequent work. Here he takes the opportunity not just to adjust his camera placement (witness the telling reverse of angle on new daddy Carlin when a warder dismisses him after advising him to watch his step), but also the manner in which some key scenes are shot. It is here that he first experimented with the 'walking shots' that would become a signature feature of his later TV work, long takes following characters as they move between locations, the most riveting and effective of which locks onto Carlin as he makes his move against Banks. This adds a very real urgency and vigour to what was already a gripping scene and is a signpost of things to come, when Clarke would later construct entire films from Steadicam walking shots (although the Steadicam was invented and in use by now, the walking shots in Scum were done hand-held), peaking with the extraordinary Elephant and Christine and a single shot in Road that still leaves me slack-jawed with amazement, though as much for Lesley Sharp's astonishing performance as the technical brilliance of the shot.

SPOILERS AHEAD – CLICK HERE TO BYPASS

Another area in which it has been claimed that the feature sensationalised a story is in the upping of the violence from the TV version, but while the violence certainly feels more charged here, the most oft-quoted examples were all in the original, at least before they fell victim to censorial scissors. The greenhouse rape and the suicide attempt by inmate Toyne were both in the TV version but fell victim to post-production trimming in an effort to appease those objecting to the prospect of it being screened at all. Indeed, I would argue that Carlin's bathroom assault on Banks is more violent in the original, the initial ramming of his head into the sink – which is captured in a single wide shot in the feature – being shown in wince-inducing close-up. Both the notorious murderball sequence and the climactic riot are virtually identical in both versions (right down to the kinetic tracking shot during the pre-riot "Dead!" chant), and lest there be anyone in these more cautious times who suspects that murderball is Minton's fanciful invention, be advised that we used to play it once a term at my humble comprehensive school, and that it really was as violent as portrayed in the film.

Where the two versions do part company a little is in the second half. In the TV original, Carlin plays a less prominent role, and in a turn of events that is not in the feature remake, he takes on a 'missus', a young male inmate he keeps with him for company and sexual gratification. This gives rise to a scene also unique to the original in which the increasingly despairing Davis, who is facing the prospect of more greenhouse work and being gang-raped a second time (I'm assuming if you're reading this that you've seen the film), goes to Carlin for help but is dismissed out of hand when he feels unable to talk in front of his now ever-present companion. This puts an interesting dent in Carlin's antihero status and makes his own failure to listen to Davis a contributory factor to his suicide, which in turn provides a much stronger motivation for Carlin to lead the riot that follows the discovery of Davis's body. In the special features, screenwriter Roy Minton expresses his bemusement at the absence of this aspect of the story in the feature, but Winstone has admitted that it was down to his then young discomfort at the homosexual aspect of the character, and being an essential component of the film he was able to persuade Clarke to drop it from the story, something he has since confirmed that he deeply regrets doing.

SPOILERS OVER

Every time I come back to Scum I'm astonished by how hard-hitting it still feels, how fresh and vibrant the performances are, how immaculately structured it is as drama, and how compellingly directed every frame of it is. As producer Clive Parsons notes in the special features, it hasn't dated at all, in part because the whole film takes places in an enclosed environment where – save for the haircuts on a couple of the warders – the fashion and technology factors that nailed so many British films of the period to their time and place in which they were made and set are simply not on display. That this feature remake is missing a key element from the original and lacks its more low-key documentary feel is a trade-off I'm prepared to take when the result is this powerful as drama and this thrilling as a cinematic experience. It remains for me one of the finest films from a time when British cinema and television could be urgent, realistic and have something worth saying, and when a select few filmmakers showed the world that they had imagination to spare and balls the size of asteroids.

I've made the mistake before of remembering a film for its gritty subject matter or handling and somehow being fooled into thinking that this is also how the film looked. That said, there is a logic to that assumption in the case of Scum, which cinematographer Phil Méheux shot primarily using available light and by replacing the incumbent fluorescent tubes with daylight-balanced ones and putting 150-watt bulbs in desk lamps. This means that entire sequences are lit from above by ceiling-mounted fluorescents with no lower-level lighting to fill in the shadows this would cast on faces. I was thus bowled over by the 1.66:1 1080p HD transfer on this Blu-ray, the result of a 2012 2K restoration from the original negative by Euro London. Yes, there are a couple of sequences when the lighting restrictions do impact a little on the image fidelity, but for the most part the film looks better here than I've ever seen it, at least since it's cinema release. The contrast is well balanced and allows for some surprisingly well-defined detail in the darker areas, and while the palette has that familiar green hue when a sequence is artificially lit, in daylit scenes the colour is winningly natural, and there's even a touch of vibrancy to the bolder hues. A fine film grain is evident, and there's not a dust spot to be seen.

A clean Linear PCM 1.0 mono track has some minor range restrictions, but this ends up working for the film by adding to its documentary feel. Dialogue is always clear and there's not a trace of hiss of fluff in the background.

Optional English subtitles for the deaf and hearing impaired have been included.

Commentary with actor Ray Winstone and Nigel Floyd

Ported over from the earlier Blue Underground Alan Clarke Collection DVD set, this is an excellent track, despite sounding a little like it was recorded in a warehouse and as if the pitch of the voices has been dialled down a couple of notches (I've never heard this actor's voice sound this deep). Winstone is typically down-to-earth and has plenty of engaging anecdotes about the making of the film. Some are well-known, such as Alan Clarke's method of firing up the actors to get stuck in during the murderball match, while others – when actor John Judd (playing warder Sands) got a bit 'realistic' when losing his rag at Banks for letting Carlin beat him and feared genuine recrimination during the riot scene – were new to me when I first heard this track back in 2004. The language is stronger than on most commentaries and even stronger than the film at one point, but this adds to the sense that you're sitting down with Winstone for a pint and a chat about the film. Pleasingly, it's a film that Winstone remains proud of and he echoes the views of other contributors to the special features when he sings the praises of Clarke's direction and confirms that he had a real way with the young cast.

Cast and Crew Interviews

Mick Ford: No Luxuries (19:18)

A terrific collection of new interviews with some of the key figures of the film's production kicks off with actor Mick Ford, who reveals that he was technically too old for the part – he was 26 at the time and already had two children – and that Alan Clarke was initially uncertain about casting him as a result. Some of the points discussed here – notably the loyalty that Alan Clarke inspired in his cast, his aversion to anything that looked like acting and the threat of real violence in the build-up to the riot scene – are also covered in other interviews from different perspectives, but Ford is one of only two interviewees who gives a mention to the alternatively titled script, The Boys in Black, so named to avoid tipping off those in authority that they were remaking a previous banned film in a government-run facility. He also reveals that while it was not anything like as unpleasant as you'd think walking barefoot in the snow, the pain that hit him when his feet began to warm up remains the worst he has experienced.

Ray Burdis: An Outbreak of Acting (15:17)

Ray Burdis, who plays Pongo Banks' crony Eckersley and is one of several actors from working-class backgrounds who started out at the Anna Scher children's theatre group (others included Kathy Burke, Phil Daniels, Natalie Cassidy, Dexter Fletcher, Pauline Quirke, Susan Tully and Gary and Martin Kemp), recalls getting cast in the original BBC play and having a second stab at the role for the film version, which he admires but doesn't think is as good as the original. He touches on the threat of a real fight breaking out during the riot scene and confirms a story told elsewhere about how Clarke wound up both sides for the murderball match and even admits that he was responsible for stealing a crew member's car and burying it in snow and he was the one who nicked the cast transport coach for a bit of a joy ride with a few of his fellow actors. His summing up of Clarke's aversion to anything came across as acting is probably my favourite: "If someone started having an outbreak of acting, Alan would say, 'Stop. Fuck off. Don't do that.'"

Perry Benson: Smashing Windows (11:05)

Benson, who plays young and vulnerable-looking child killer Formby, kicks off by amusingly claiming to be glad Billy Cotton banned the TV original so that he could land a role he looked too young to play in that version. He confirms a story told by others that when they shot the film in a disused wing at Shenley Psychiatric Hospital it was still a functioning institution, and adds to the stories of the trouble that nearly kicked off during the riot scene by recalling a pile of weapons confiscated from the kids they had hired just for that sequence. He still holds Scum in high esteem but finds hit difficult to watch, though cites the even tougher Elephant as a personal Clarke favourite and recalls working with him again on Stars of the Roller Skate Disco in 1984.

Phil Méheux: Continuous Tension (17:59)

Cinematographer Phil Méheux begins with an interesting story about how he nearly got to shoot the TV original and recalls how he landed the job of shooting the feature remake. He discusses having to light the film entirely with practicals to allow complete freedom of movement for the actors and the camera, and how this added to its documentary feel. He confirms that he operated the camera himself (and man, does this guy know his job on this score) and notes how the long track with Carlin in the build-up to his confrontation with Banks helps to build tension. He also has some info on the shooting of the riot scene, and an opinion (that I share) on how the absence of Carlin's 'missus' in the film's later stages softens it a tad when compared to the original.

Martin Campbell: Criminal Record (9:19)

The film's line producer (look it up if the term is unfamiliar) recalls how the film came to be and has a couple of engaging stories about Alan Clarke, whom he describes as being highly respected, a heavy drinker, very rebellious and with a great sense of humour, and who as a director who would create such a great atmosphere on set that the young actors would give their all for him. He regards Scum as one of the best and most important British films of the 1970s (and it is), but claims it was shot in a disused wing of an actual borstal, which differs from all other recollections on this disc.

Don Boyd: Back to Borstal (31:23)

The film's executive producer Don Boyd, who is also a film and television director, recalls hearing about the banning of the TV version and outlines how the film version was kicked off and went into production. Like a number of others here, he contradicts Martin Campbell's recollection of where the film was shot, but does provide confirmation of writer Roy Minton's unhappy memories (you find this in the archive interviews section of this disc) of attempts by the otherwise excellent producers Clive Parsons and Davina Belling to soften the film in order to make it more commercial, and a small battle Clarke had with them at the editing stage over his refusal to add music and their insistence that a key suicide sequence be cut. To his considerable credit, Boyd overruled them on each score and it's thus in no small part due to him that we have the film as it is today. He recalls the film's first screening at the Prince Charles Cinema in London and Clarke's horrified reaction to racist cheering that accompanied Carlin's defeat of black daddy Baldy, promoting the film in Cannes with Clarke and Ray Winstone, and seeing history repeat itself when its first TV screening was prevented by a private injunction taken out by Mary Whitehouse, an appalling self-appointed 'moral guardian' who was the bane of my film and TV viewing youth. He also recalls with some glee that when the film was finally screened on Channel 4, it did so on the night of Margaret Thatcher's second election victory and pulled in a sizeable audience. I really enjoyed this interview.

Michael Bradsell: Concealing the Art (29:30)

Editor Michael Bradsell, who neatly describes editing as "the art of concealing art," remembers landing the job of editing Scum and talks about some of the specifics of film and TV editing, or more specifically how he likes to approach the process. On this score he makes a good case for being able to start editing scenes almost as soon as they are processed and likens why he prefers not to have the director in the editing room to being a conjuror and having someone see how you do the trick instead of surprising them with it. He talks about the easiest scene to edit and the two hardest (these shouldn't surprise you), and coming back to the film for the first time after many years was impressed by how hard-hitting it still is and the poetic fluidity of some of the more complex camera moves.

Esta Charkham: That Kind of Casting (21:43)

The film's effervescent casting director, Esta Charkham, recalls first meeting Alan Clarke as an actor and being cast by him in Everybody Say Cheese, one of his entries into the BBC Play for Today series and being hired by Clarke for Scum once she moved into casting. She provides snippets of information on almost every actor who has a speaking part in the film, on the way confirming a throwaway comment made by Ray Winstone on his commentary track that he was cast by Clarke because of his walk. Usefully, she provides some real detail on Anna Scher and her children's theatre group, something that gets a passing mention in at least half of the interviews on this disc but which most viewers will know little about. A most enjoyable chat.

Archive Interviews

Roy Minton and Clive Parsons (15:55)

Originating on the 1999 Odyssey DVD and included in Blue Underground's Alan Clarke Collection, the inclusion here of this pair of EPK interviews is important for the contribution of producer Clive Parsons, who talks about the banning of the TV original, the inception of the film version, the controversy it provoked and the support it garnered, and why he believes it hasn't dated. Minton comments on the element from the original that is missing from the remake and reveals that during the course of his research he met a man on whom Archer was partially modelled. If this featurette was shorn of its film clips I'm guessing it would run for eight minutes at most.

Roy Minton (18:54)

Writer Roy Minton remembers originally proposing the TV version as part of a trilogy with Clarke as director, then writing Scum in about two weeks after being told that the funding was only there for a single film and getting valuable but disturbing information on what happened inside borstals from a "stupidly open" warder. The problems of getting the movie version made are also covered in some detail and differ slightly from other recollections on this disc (there's a sense that the true story is an amalgamation of them all), and he also has very unhappy memories of how his script was savaged and how his previously close relationship with Clarke deteriorated to the point where Clarke told him to fuck off and he responded by telling Clarke that he'd kill him. The disagreements were settled in a meeting arranged by executive producer Don Boyd, but Clarke and Minton's friendship effectively ended there and the two only patched things up when Clarke was on his death bed.

Davina Belling and Clive Parsons (8:24)

In this second imported interview with Clive Parsons, he is joined by co-producer Davina Belling making her only appearance in any extra on this disc. Between them they outline how they first became interested in the project, the process of getting the film financed, the limitations of landing an X certificate, the mixed reviews, and the casting change for Archer and the expansion of his character. Belling admits that the pressure to trim the suicide scene came from her claim that she nearly fainted when she saw the rushes, and she praises Clarke as a director, particularly of young actors.

Don Boyd (12:17)

An earlier interview with executive producer Don Boyd covers much of the ground – albeit more briefly – as the longer and more recent interview detailed above, including the problems with the rewritten script, the pressures applied to Clarke to make damaging changes at the editing stage, Clarke's horror at the audience reaction to one scene at the premiere screening, and the controversy caused by its first TV screening. He also says of the film's fate at Cannes that other people in the British film industry "stuck it to us" but tactfully elects not to expand on that.

Cast Memories (16:42)

An archive featurette built around interviews with actors Phil Daniels, David Threlfall, Mick Ford and Julian Firth. Daniels talks about the difficulty of repeating the role he played in the TV version for the film, assures us that after a day working on Scum you knew about it, and nicely sums up Clarke's direction as "Get in there my son!" Firth remembers his memorable final scene being tougher to play than the notorious greenhouse sequence and being invited to come along and watch the filming of riot scene even though he wasn't part of it. David Threlfall and Mick Ford both share their feelings about Archer as a character (this is where the Ford quoted used in the main review is sourced from), and Ford recalls how terrifying the riot scene was to film and the warning delivered by Clarke about what would happen if anyone took it upon themselves to injure anyone for real.

'U' Theatrical Trailer (1:05)

A trailer that makes a virtue of its 'U' certificate by reminding us that the TV play was banned and assuring us (rightly, as it happens) that there are some scenes so strong they can't be shown in this trailer. Since it's made up entirely from stills, it would have been a bit difficult to include them anyway.

'X' Theatrical Trailer (2:27)

Ray Winstone provides narration as Carlin's viewpoint in a trailer with way too many spoilers to be safely watched before the film itself.

Image Gallery

83 slides of promotional stills (some taken during the filming from angles not used in the film itself), behind-the-scenes photos and posters.

Booklet

Even by Indicator's high standards this booklet is a bit of a beauty, weighing in at a hefty 78 pages and kicking off with a really well observed and written essay on the film by Ashley Clark titled This is the Way, Step Inside, one that neatly describes the film as "a very British nightmare" and the opening transportation of Carlin, Davis and Angel as "three young lambs to the borstal slaughter." Nice. Next up we have some extracts from Richard Kelly's oral history of director Alan Clarke, and while I know I seem to say this every time I even touch on one of Clarke's films or TV plays, but if you're a fan of Clarke's work you absolutely should get your hands on this excellent book. The extracts here should give you a taste. Following this we have an on-set report by The Guardian'sfilm and theatrecritic of the day, Michael Billington, a fascinating piece that also gives some insight into the research carried out by Minton and Clarke prior to the writing of the script. There are some intriguing Producer's Viewing Notes recorded by Michael Relph in 1979 – pleasingly, few of them appear to have been implemented by Clarke. Up next is a 1979 article from the Newcastle Evening Chronicle triggered by the decision by Newcastle City Council to ban the film on its initial release, a piece that includes a few choice quotes from Clarke about the controversy the film triggered. There's a short but intriguing piece on the novelisation of the film (I wasn't even aware this existed), after which is an article on the attempt by Mary Whitehouse to ban Channel 4 from screening a film that she didn't approve of. Even after all this time, just seeing her bloody picture made me angry. Bringing up the rear are extracts from some of the contemporary reviews. Also peppering the booklet are poster reproductions, stills and scans of documents relating to the film's production. As ever, full credits for the film are also on board.

Scum is one of the films that really impacted me in my youth, thrilling me as cinema and built around characters I was able to relate to and might even have been one of had events in my life taken a different turn. It remains a tough watch, in part for the realistic presentation of its violence and a couple of still-harrowing scenes, but also for the way in which racism is employed as a weapon of bullying, which should have all but the more diehard UKIP supporters wincing but is absolutely true to the location and era and should be shown and seen for precisely what it was. This is kick-bollocks British cinema at its finest, and a terrific work from one of our very finest filmmakers. Indicator's Blu-ray boasts an excellent transfer and is loaded to the gills with first-rate special features – the only thing missing is the original BBC play, but the rights to that are currently with the BFI and it's included in the label's magnificent Dissent and Disruption box set, which every Alan Clarke fan should already own. No question, this is one of my favourite Blu-ray releases of 2019 so far, and gets our very highest recommendation.

|