|

In

a cinema-going sense, I grew up on kung-fu movies. They

arrived in the UK a few years too early for me to legally get into the cinemas at which they were screening, and in these pre-video days that was the

only way you were going to see them. They were the talk

of the school playground but were all X-rated,

the long-ago equivalent of today's 18 certificate. Fine

for the sixth-formers, who could pull off the I'm-older-than-I-look

bullshit to the more gullible or sympathetic box-office

guardians, but a near-impossible task for us 13-to-14-year-olds.

But the draw was considerable, and two of us, who were tall and

scraggy-looking for our age, decided we'd try it on, figuring

that we might get away with it purely because no-one would

expect anyone that young to attempt such a ludicrous

deception. Both of us were nervous but determined to go

ahead with it. Then, the day before we were due to make

our play, my friend chickened out. I was mortified – how

could I possibly do this on my own? Then I did something really

stupid and got the surprise of my life. I told my mother

what we'd been planning. I can't remember why, but I did.

To my utter astonishment, her reaction was not admonishment,

but this: "Well if he won't go with you, sod him.

Go on your own." I thus dressed up like an office

worker, put on my best air of false confidence, lowered

my voice a couple of octaves and off I went. To my dizzying

delight, they bought it. The film was Chang-hwa Jeong's King Boxer (1973), which is also known as Five

Fingers of Death. Needless to say, I'd never

seen anything like it. In the following five years I lied

my way into everything that Hong Kong action cinema (and

in the case of Enter the Dragon, Hollywood)

saw fit to throw in our direction and became utterly enamoured

with Bruce Lee, the man history has rightly credited as the genre's

greatest star. Ironically, by the time I was

old enough to see the X-rated films legitimately, the

first kung-fu cycle had all but burnt itself out.

The

second wave had its own superstar, a young, insanely acrobatic

fighter named Jackie Chan. Chan upped the action level

and deftly combined it with a physical comedy that harked

back to the silent film acrobatics of Buster Keaton and

Harold Lloyd. Like Bruce Lee, Chan had his own distinctive

screen persona and fighting style, creating in the process

very specific expectations of what constituted 'a Jackie

Chan film', something that was diluted

by a later move to America.

Since

then other stars have risen and been borrowed by Hollywood

(Jet Li being one of the most notable), and the traditional

kung-fu film has lost popularity to the Chinese Wuxia fantasy following the phenomenal international success

of Ang Lee's Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon and Zhang Yimou's Hero and House

of Flying Daggers, while Stephen Chow has kept the

genre's comedic element alive with the likes of God

of Cookery, Shaolin Soccer and Kung Fu Hustle.

Hollywood began plundering the techniques of the Wuxia films,

and the computer-enhanced wire work and high-speed editing

techniques, for all their visual elegance, made it harder

to appreciate the physicality of the performers. But that,

it would seem, is about to change.

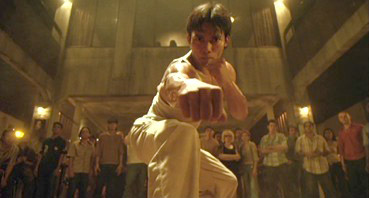

Ong-Bak arrived in the UK on the back of some tantalising pre-release

publicity. Showcasing the talents of a new action star

in the shape of Tony Jaa, the film proudly announced that

it contained no wire work or CGI, and that all of

the sometimes spectacular stunt work was carried out by

the performers rather than stunt doubles. I, for one, was intrigued, even more so when I learned that the film originated not from Hong Kong as expected, but Thailand.

I

have to admit that my exposure to Thai cinema has been

somewhat limited but always memorable: Wisit Sasanatieng's

2000 Tears of the Black Tiger, Pen-Ek

Ratanaruang's 2001 Monrak Transistor and Apichatpong Weerasethakul's 2004 Tropical

Malady are three of the more distinctive world

cinema releases of recent years, and The Pang Brothers

have made a substantial international impact with the

likes of Bangkok Dangerous and The

Eye. Little did I know that Thai action cinema

was also on the way to becoming a force to be reckoned

with on the world stage, and that Ong-Bak and the very considerable talents of one Tony Jaa were

the to be the opening fusillade.

Martial

arts movie plots and characters of years past often

followed similar, even simplistic lines. Heroes were kind-hearted

innocents caught up in dastardly plots through no fault

of their own, bad guys were really bad and backed up by

armies of violent henchmen,* and the two usually came

into conflict after honour was offended and/or a family

member or wise old sifu was maimed or killed. Not that this ever mattered.

Like the fall-in/fall-out relationships of musicals

and the here-to-fix-the-gas-meter shenanigans of porn

movies, these plots functioned purely to transport the

characters from one set-piece to another, and it was these scenes that the audience handed over their dosh to see.

It

is this very model that provides the set up for Ong-Bak,

whose opening scenes display a sense of innocence that

borders on parody but which are played utterly straight, as if the tragic mythology of Crouching Tiger et al had never taken place. Set in the village

of Nong Pra-du, where the people are poor but spiritual,

the villagers are mortified when the head of Ong-Bak,

their temple's statue of Buddha, is stolen by outsiders.

Step forward the athletic and orphaned Ting, who was raised by

local monks and skilled in the ancient fighting art of

Muay Thai, and who volunteers to travel to Bangkok and track

down and return the head. On his arrival, he stumbles across street-hustler

George (played energetically by comedian Petchtai Wongkamlao),** who also hails from Nong Pra-du but is hiding from his

past and is accompanied by a young cohort named Muay Lek (Pumwaree Yodkamol).

The three eventually form an uneasy alliance to search

for the missing head.

If

the plot preamble harks back to earlier generic times

then so does the technique. The film-makers have made

no secret of their admiration for the cinema of both Bruce

Lee and Jackie Chan, and this is clearly visible in the

structure of the narrative and some of the set-pieces.

Ting's agility and fighting skills are very effectively

hinted at early on as he practices his moves, but like

Lee in The Big Boss, he repeatedly shies

away from demonstrating them on others, a very effective

tease that is heightened by his single blow defeat of an

opponent when he unknowingly wanders into the ring at

an illegal fight club. A short scuffle later he is being

chased down back-streets and performing a range of spectacular

stunts in a sequence that inevitably recalls the street

acrobatics of Jackie Chan, a link accentuated by the comic

mirroring of his actions by the hapless George, who here

provides the film's funniest laugh-out-loud

gag. It will take a return to the fight club and a lot

more provocation before Ting really gets to show what

he's made of. By then even the more casual martial

arts movie viewer will be fully aware that, despite its

influences, Ong-Bak is no post-Jet Li

knock-off, but something new, and something potentially very

exciting for the genre's future.

The

first thing that marks Ong-Bak out is

its very evident national identity. The language, facial

features and customs all give the film a feel that immediately

distances it from its Hong Kong cousins, while its open embracement

of Buddhism and Buddhist principals very much reflect

the beliefs of its domestic audience (Ting's initial refusal

to fight and preference for pushing people aside rather

than thumping them comes not from a promise to his mum

but his religious convictions). But most startling is

the Muay Thai fighting technique itself, a still-practiced

ring sport that uses elbows and knees as much as fists

and feet, and as presented here is a martial art of exceptional

brutality – when Ting leaps through the air and brings

his elbow crashing down on the top of an opponent's head

there will be few who will not wince at the real-world

consequences of such an attack. Indeed, it was this very

element that prompted Jackie Chan, of all people, to wonder

if the film was perhaps too violent, and on his

commentary track Bey Logan on three separate occasions

pleads with watching fans not to try this at home.

Combining

the elegance of kung-fu with the street-level viciousness

of Hard Times' bare-knuckle boxing, Muay

Thai delivers as both a balletic screen spectacle and

a thumpingly impressive method of unarmed combat. Stripped

of the wire work and CGI, the fights have a physicality

to them that is both refreshing and at times a little

alarming. There are no faked angles or pulled punches

here, they all make visible contact and are accompanied

not by the famed but exaggerated whack of traditional kung-fu wallops,

but earthily realistic body contact sounds. When blows

land here, you feel them. Despite their still choreographed

nature, this is probably as realistic as martial arts

fights have looked and sounded in a long while.

Director

Prachya Pinkaew forges further links to the genre's roots

by abandoning the create-in-the-edit technique of many

recent genre works (and especially western action films

that have borrowed them), his camera placement always

showcasing the skills of his performers instead of blurring

them in a blizzard of fast-cut close-ups. Not that this

affects the pace of the film in any way – it fairly belts

from one scene to the next, Nattawat Kittikhun's often

mobile camera infusing the action scenes with a visual

urgency that very effectively matches that of the performers.

All

of which would still make Ong-Bak an

efficient but potentially run-of-the-mill action outing

were it not for one, very important component: Tony Jaa.

Seeing him in Ong-Bak is one of those

skin-prickling moments in your viewing career, like catching

Bruce Lee for the first time in The Big Boss or Jackie Chan in Young Master, when

you know you are witness to the start of something big.

Jaa is an extraordinarily agile and dexterous athlete

whose unusually rock-solid fighting stance can explode

with graceful brutality in a literal blink of an eye.

As a film fighter he is phenomenal, but as a screen presence

he in many ways kicks against the genre norm – there is

no comic mugging or iconic vocalisation, Jaa's everyman

looks and disarmingly low-key acting at times giving him

the feel of a background character rather than the star.

If part of a movie hero's job is to provide a figure for

audience identification and wish-fulfilment, then Jaa

succeeds in a way that few have done before, an ordinary

guy who is pure of heart and can beat people six ways

from Sunday. Whether this persona is a one-film deal or

not only time will tell, but here it works a treat, creating

a likeable character who also happens to be an atomic

force for good.

As

a vehicle for launching a major new talent onto the international

market, Ong-Bak is right up there with

the best. The story has few surprises, but on every other

level the film delivers in spades, leaping energetically

from one memorable set piece to the next without ever

repeating itself, sprinkling the action with humour and

even throwing in a vehicle chase that is unlike any other

you'll have come across recently. For genre fans this

is a rare treat, a martial arts film that draws on the

past and yet delivers something new, and does so with

considerable style. If there's any justice then Tony Jaa, Prachya Pinkaew and Muay

Thai itself are all going to be big time on the martial

arts action scene. For once it's OK to believe

the hype. Just don't try it at home.

Framed

at 1.85:1 and anamorphically enhanced, this is a very

good transfer that copes well with the film's bronze-tinted

interiors, though occasionally compression artefacts can

be seen in areas of similar colour. The tonal range is

good, as are the contrast and black levels, and the picture

is sharp without obvious evidence of enhancement. Colours

in the non-tinted scenes – the tuk-tuk chase is a good

example – appear solid.

The subtitles appear to be dub-titles, matching the English

dub in most respects, right down to the use of the word

'wanker', an unlikely insult in the back streets of Bangkok.

They are clear enough, but of surprisingly low resolution,

looking like they were created using Deluxe Paint on

a Commodore Amiga.

There

are three soundtracks on offer, Thai 5.1, Thai DTS, and

a 5.1 English dub. The first thing that you notice is

how much louder the DTS track is than the 5.1, but cranking

up the 5.1 track gives the DTS the edge in other areas,

the crisper trebles matched by a fuller use of lower frequencies.

This is particularly noticeable when the music kicks in.

I

don't like English dubs of foriegn language films for a variety of reasons, no matter how

well done they are – the director's lack of involvement

in this crucial aspect of the film, the changing of dialogue

to fit mouth movements, the loss of the sound and inflection

of the language, and so on. Here the dub is performed

with enthusiasm, but in the process Bangkok has become

East Stepney, as a range of colourful mockney voices are

attached to characters, some of which (George in particular)

just don't work at all. As is often the case, the voices have not

been processed to sound like they were recorded on location,

and so always seem dislocated from the action. Strangely,

villainous crime lord Khom Tuan is played like Ron Moody's

Fagin from Oliver!

My

only real complaint here is not about what's included,

but what's missing. The movie has been re-scored for its

UK release after it was deemed that the original, more

traditionally Thai music would not play as well in western

markets. Frankly I would like the opportunity

to judge that for myself, and would really have appreciated

a track that included that score. It was good enough for

director Prachya Pinkaew, and he seems to know what he's

doing.

If

there's one thing that instantly gives many region 2 martial

arts DVD releases a huge edge over their region 1 cousins

it's the inclusion of a commentary track by Eastern cinema expert Bey Logan. An industry insider

with a huge knowledge of martial arts cinema, he has met

and worked with a fair number of those appearing in the

films he comments on, but still takes a true genre fan's

delight in their work. This is a typically excellent Logan

commentary, crammed with facts about the filming and the

actors (even bit part players are covered in detail), information

on the various influences, the aforementioned warnings about

using Muay Thai on others, and even a cheerful protestation

about a visual trick used in the film that was originally

his idea. All of this is delivered with barely a pause for

breath, but Logan still takes time out to marvel at Tony

Jaa's skill, cutting himself short at one point to remark

in an awed voice, "Now that is just extraordinary!"

as Jaa performs one of his more jaw-dropping moves. He also

talks in some detail about the cuts made to the French release

by Luc Besson (whom he also credits as being one of Jaa's

earliest champions), and the new score created specifically

for this version.

The

extras on the second disk are divided into three sections. The Cutting Room Floor has eight short deleted

scenes, all non-anamorphic widescreen and

some way short of perfect, with iffy contrast and definition,

and artefacts dancing around the screen in the manner of

low compression mpeg files. Sound is also less than pristine

(and not there at all at one point), but they are nonetheless

a very important inclusion, most of them having been directly

referred to in the commentary, including the alternate ending.

The first four are from the same sequence. You also get

a brief aural glimpse of what sounds like the original Thai

score. All are subtitled in the Amiga font.

The

Promotional Archive has five entries, all but one of

which are anamorphic 16:9.

Ong-Bak

on Tour (3:01) covers what appears to be the

Thai premiere, at which Tony Jaa signs autographs and performs

some of his fighting moves and stunts live for the assembled

crowds, intercut with extracts from the film in which the

moves appeared.

The

Art of Muay Thai (24:05) looks at the philosophy

and techniques of Muay Thai and features the masters and

students of the Sor Vorapin boxing gym in Bangkok. Some

of this is conducted in English, and the trainer with the

heavier accent is subtitled, but this can be switched off

if you find it a little condescending. A very clear explanation

is provided of the rules of Muay Thai fights and the training

required (and the early age at which you are expected to

start). One dangerous-looking Thai boxer claims that only

Thai people can properly use this fighting style, but later

admits that some of the foreign fighters regularly win competitions

there. He also liked Ong-Bak a lot. If

Muay Thai boxing is a new experience for you, this is an

informative and enjoyable introduction.

The UK promotional trailer (2:10)

gives a nice flavour of the film, even if it is narrated

by Trailer Voice Man. Sound on this is 5.1.

The

Road to Glory: The Making of Ong-Bak (76:43)

is a near feature-length look behind the scenes at the making

of the film. Shot on DV (this is the only extra in this section framed

4:3), it features a running commentary by director

Prachya Pinkaew, co-writer of the original story Phanna

Rithikrai, and Tony Jaa, credited here by his real name Phanom

Yeerum. Divided into eight chapters, this is a wonderful

extra feature, providing a comprehensive look at the making

of construction of some of the film's most memorable action

sequences, combining rehearsal material (the film had an

extraordinary four-year rehearsal period, and was constructed

almost in total on DV before a frame of film was shot) with

footage of the shoot itself and extracts from the film.

There is a wealth of fascinating stuff here, and if anything

seeing the fights and stunts performed in one, uninterrupted

take increases your respect for Jaa and his stunt crew even

further. A number of injuries are shown, including a bad

landing that resulted in torn ligaments for Jaa and suspension

of shooting for several months. Your sense of relief at

the safety precautions taken is countered somewhat by seeing

just how hard the performers hit each other to get the desired

effect.

From

Dust to Glory: An Interview with Leading Man Tony Jaa (3:46) is taken from what appears to be an Australian movie

show, whose female host talks not just to Jaa, but also,

briefly, director Prachya Pinkaew.

The

third and final section, Fight Club, has four subsections.

Visible Secret: Rehearsal Footage Montage (4:04) consists of footage of Tony Jaa and stuntman Don

Ferguson blocking out ideas for the fight club scene. This

is 35mm footage shot specifically to demonstrate the moves

to the actors who would be playing the scene in the movie

proper.

The

Bodyguard: An Interview with Don Ferguson (10:05)

has Canadian stuntman and Tae-Kwon-do champion Don Ferguson

talk about his experiences in working on the film.

Mad

Dog: An Interview with David Ismalone (11:33)

is in a similar style to the above and shot in the same

location. Ismalone, a French fighter who like Ferguson is

resident in Thailand, plays Mad Dog, the plate, chair and

fridge-throwing opponent in the fight club scene. The interview

is conducted in English.

Pearl

Harbour: An Interview with Erik Markus Sheutz (13:54) has German Thai boxer Erik Markus Sheutz talk about

his early experiences with Muay Thai, his career change

to stuntman and his experiences working on Ong-Bak as Jaa's

first opponent in the fight club. Sheutz is chatty and interesting

and talks in very fluent English.

Some

have complained at Ong-Bak's unadventurous

plotting, but those familiar with the genre will know this

is a moot point, considering its purpose is solely to shuttle

us from one action sequence to the next. Given my disdain

for the simplistic plots and characters that curse most

modern Hollywood products this may sound somewhat hypocritical,

but if an action movie flies or dies by its set pieces then Ong-Bak soars. The astonishing acrobatics

and fighting skills of Tony Jaa and his team, the exuberant

direction of Prachya Pinkaew and the sheer inventiveness

of the stunts and fights make this the single most exciting

martial arts film to hit these shores in years.

Premiere Asia have done the film proud with this Platinum

Edition release, with strong picture and sound, a typically

fine Bey Logan commentary, and a collection of very good

special features, the shining star of which has to be the 77 minute

making-of documentary, which as well as being fascinating

viewing includes a commentary by the director, lead actor

and co-writer, effectively substituting for a filmmaker's

commentary on the film itself. My only regret, as stated

above, is the lack of the original Thai music score, which

must count as a woefully missed opportunity on what otherwise

comes close to being the definitive DVD edition of the film.

That aside, this is a must-buy for all fans of of the film

and of martial arts cinema in general.

*

This was hilariously sent up in Stephen Chow's Shaolin

Soccer, whose insanely nasty bad guys actually

called themselves 'The Evil Team'.

**

His village name is Humlae, but the literal translation

of his adopted name is apparently 'Dirty Balls'.

|