|

There's a glorious moment in the first twenty minutes of Tony Jaa's breakthrough movie Ong-bak, when he wanders inadvertently into a fight club arena and defeats his opponent in the blink of an eye. It works so well in part because we've already been clued into the fact that he is a fighter of some considerable skill, and this first demonstration of his talents is teasingly delayed to the point where we're expecting a virtual explosion of dazzling kicks and punches. Yet against all expectations, Jaa floors his attacker with a single kick, and does so with the distracted air of someone brushing off a persistent fly. In a contest in which the contestants beat each other silly for minutes at a time, the casual ease of Jaa's victory here speaks volumes about his likely capabilities. It's a trick also employed by Brad Pitt and a single sword thrust in Troy, but beating them both to the punch, so to speak, was Charles Bronson in former screenwriter Walter Hill's terrific directorial debut, Hard Times.

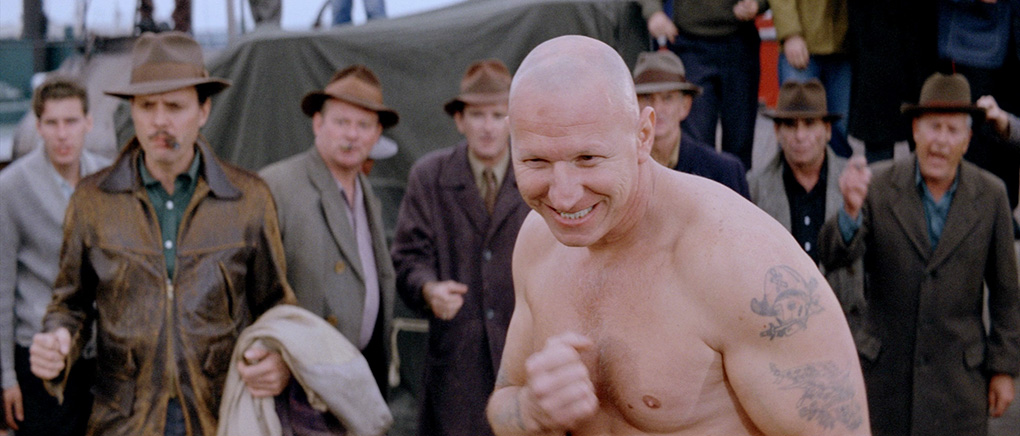

Here Bronson plays Chaney, a middle-aged drifter who arrives in New Orleans during the Great Depression and stumbles across an organised illegal street fight. Once the bout has concluded, Chaney approaches the loser's manager, a fast-talking opportunist named Speed (James Coburn), and offers his services. In common with seemingly past-it baseball hopeful Roy Hobbs in the later The Natural, Chaney is initially mocked and dismissed for being too old, but when he steps up to the proverbial plate he flattens his opponent with a single punch. In no time at all, Speed has introduced him to opium-addicted ringside cutman Poe (Strother Martin) and is setting him up to fight the formidable and as-yet undefeated Jim Henry (Robert Tessier, as imposing a presence here as he was as homicidal prisoner Shokner in The Longest Yard). But before this particular contest can take place, Speed has to raise the $3,000 stake demanded by Henry's wealthy manager Chick Gandil (Michael McGuire), the lion's share of which Speed borrows from local mobster Doty (Bruce Glover). In Chaney, Speed sees an opportunity to get rich, but early on in their partnership Chaney informs him that once he has the winnings he needs, he'll be moving on, and Speed has a habit of gambling away money almost as soon as he makes it.

It takes some balls on the part of those funding the first feature of any untested director to agree to bankroll a period piece. It complicates every scene, requiring the procurement of appropriate costumes, vehicles, furniture and fittings and the removal of any anachronistic details. It also severely narrows your choice of locations and the angles from which you can shoot when you get there. At a time when entire streets can be replaced using photorealistic CGI, this may not seem like such a big deal, but back in 1975 this all had to be achieved through physical means and would bump up the cost of every scene and present its share of logistical headaches. Yet the period setting here is essential to the story, distancing the brutality of a form of fighting that would have uglier connotations in a contemporary setting, at the same time casting Chaney not as a hard-ass brute but as a working man looking to get by the only way he knows how in a catastrophic time for the poor and downtrodden.

I don't know how many of you have actually been in a fist fight, but I was in quite a few in my misspent youth, and remember clearly that unless both participants were built like proverbial brick shithouses or couldn't throw a punch to save their lives, they didn't last long. On one occasion, I was knocked out with the first punch, suffering exactly the same fate as Chaney's first opponent here. Bare knuckle fights really are brutal affairs, and if you fancy pondering on just how much damage a well-delivered thump in the face can do, imagine any professional boxer of note landing one on you but without the slightly cushioning protection of a boxing glove. Such punches delivered by muscular fighters can break bones, knock out teeth and tear open skin. Here, however, the combatants come out of each fight a tad dazed but with little in the way of visible scars. In that respect, the impressively staged fights in Hard Times are as stylised at the fabulously choreographed street battles in Hill's third film, The Warriors, their violence communicated not through bloody injuries but the loud (if artificial) thwack of fists against face and the muscularity and clear physical strength of the actors.

In Chaney, Hill creates the sort of stoic anti-hero that would get carried through to his second film, The Driver, whose pared-down characters are never identified by name but by their roles in story and become almost interchangeable with the machines with which they ply their trade. Like Ryan O'Neal's Driver in the later film, Chaney is a man of few words and locked-down emotions, one destined from the start to eventually leave the story alone and on his own terms, in spite of the on-off relationship he strikes up with the lonely Lucy (played, apparently on Bronson's insistence, but his then wife Jill Ireland) that intermittently shows signs of developing into something more substantial. Even the apartment he rents is every bit as sparsely decorated as the one in which the Driver choses to rest his head.

There is a degree of inevitability to some of the story arcs, and it will probably come as no surprise that the opponents Chaney faces increase in difficulty as the story progresses and climax in a make-or-break fight that he may not win. That the relationship between Chaney and Speed will hit a rough patch at a crucial moment for both is also on the cards from an early stage, their mismatch of personalities almost a trial run for the one between Ryan O'Neal's Driver and Bruce Dern's chatterbox Detective in Hill's follow-up film. But Hard Times still proves disarmingly compelling viewing, for its characters, its convincing period setting, it's rich background detail (there are exteriors here whose scale genuinely belies the film's modest budget), and the impressive restraint of Hill's consistently confident handling. Chaney in particular is a fascinating enigma, one whose backstory and specific motivation – he plans to fight only until he has secured a specific amount of money, but for what we are never told – remains a mystery right up until the final credits roll. And when Speed is cheated of his winnings after Chaney has successfully defeated an opponent in Cajun country (a scene whose integration of drama and music can't help but anticipate the later Southern Comfort), it's the taciturn Chaney who knows just how to put things right.

Although not Hill's first choice (he wanted the younger – and frankly less interesting – Jan-Michael Vincent), Bronson is spot-on casting here, his weather-beaten features and imposing physicality completely selling him as a down-on-his-luck working man whose fight skills have been learned and earned on the streets. In the restraint of his performance, Bronson is at his Once Upon a Time in the West best here, communicating as much through a look or the control of his body language as he does through his carefully rationed words. As Speed, James Coburn is almost his polar opposite, his talkative manner and easily flashed smile combining with a physical twitchiness to suggests a man who is constantly on the lookout for a chance to make money whilst simultaneously watching his back. Solid support is provided by old hand Strother Martin as the easy-going Poe, and despite being forced on the director, Jill Ireland does fine as the world-weary Lucy.

Originally released in the UK under its original script title of The Streetfighter (word has it that the title change here was made to sidestep the suggestion that this was an adaptation of Charles Dickens' novel of the same name), Hard Times was a strong calling card for its screenwriter-turned-director, and marked the beginning of a seriously impressive run of distinctive and character-based (if largely male-centric) action movies – The Driver, The Warriors, The Long Riders, Southern Comfort, 48 Hrs. and Streets of Fire – that really put Walter Hill's name on the directorial map. It's a damned fine first feature, one that looks as good as – kudos to Philip H. Lathrop's evocative scope cinematography and Trevor Williams' art direction – and for me plays every bit as well now as it did back on its cinema release. It's also a far better showcase for the then middle-aged Bronson's considerable talents than the Death Wish films for which he is too often remembered.

A handsome 2.40:1 HD transfer from a 4K restoration that really flatters Philip Lathrop's period scope cinematography. The contrast range is attractively rendered, with beefy black levels throughout that only pull in shadow detail when the lighting dictates that it logically should. The warm, sepia-tinged tones of the colour palette are attractively rendered, and the sharpness and image detail are both impressive, though there are a small smattering of shots in the first third where the sharpness is a little soft, which the consistency elsewhere suggests is down to the source material.

The Linear PCM 1.0 mono soundtrack is a little range-restricted but is otherwise in good shape, with clear rendition of dialogue, sound effects (the punches register as loudly as I remember) and, especially, Barry DeVorzon's score. Also available is a DTS-HD 5,1 Master Audio surround track, which spreads the music a little wider and adds a tad more finesse.

Optional English subtitles for the deaf and hearing impaired are available.

NFT Audio Interview with Director Walter Hill (31:32)

An on-stage interview recorded, I'm guessing, sometime in the early-to-mid 1980s (I'm going by the films that are referenced during the course of the discussion) and conducted by a master of deadpan questioning, with a switch to barely audible questions from the audience halfway through. Despite the less than pristine audio quality, this is still a valuable grab, one in which Hill talks about not overloading his characters with psychological baggage, how most of his films are about how the characters react to the narrative, his desire to make more westerns, casting first-timer Eddie Murphy in 48 Hrs., choreographing film fights, his journey to direction via scriptwriting, working with Sam Peckinpah on The Getaway, and more.

Walter Hill: Fisticuffs (20:40)

A more recent interview with director Walter Hill that is focussed primarily on the making of Hard Times. Here he outlines how he landed his first directing job, the reason for his pared-down approach to the drama, his admiration for Bronson and his performance in a role he initially resisted casting him in, the reasons for James Coburn's reluctance to do the film, the difficulty he and producer Lawrence Gordon had casting the role of Poe, learning about direction from cinematographer Philip Lathrop, and plenty more.

Interview with producer Lawrence Gordon (14:04)

Producer Lawrence Gordon, who has worked with Walter Hill on seven films in total, talks about how Hard Times first came about, landing Charles Bronson against the odds, some of the problems that arose from working with Bronson and James Coburn, and his happy relationship with Hill over the course of their subsequent films together. He confirms that he was very pleased with the finished film, but reveals that Bronson was not and insisted on a number of changes, which he and Hill successfully resisted making.

Interview with Composer Barry DeVorzon (8:42)

Score composer Barry DeVorzon – whose radically different work on Hill's later The Warriors had a major impact on my teenage years – reveals his personal approach to scoring a film, how he came to Hard Times via his work on John Milius's Dillinger, and how adding music can soften the violence of a scene (there's none on the fights in Hard Times, whereas every battle in The Warriors is scored).

Original Theatrical Trailer (2:23)

Not bad, but there are a few spoilers.

Also promised for the release version is a Booklet featuring new and archival writing and rare archival imagery, but this was not available for review.

A hugely enjoyable first feature from Walter Hill that impressively underplays a story that most would have run with. Bronson has rarely been better or more effectively cast, and he's backed by a most engaging supporting cast and given decent material to work with. It's great to see Eureka picking up titles that once would have been dismissed by more highbrow critics for the Masters of Cinema series, and this release has done the film proud. Highly recommended.

|