|

Despite considerable differences in age, background and life experience, there are certain things on which several of the reviewers on this site seem uncannily united. One is our love for the TV Sherlock Holmes films starring Jeremy Brett and David Burke. Another is our passion for movie soundtracks. I will admit that I tend to be a reactive soundtrack collector, hunting them down only after I've seen the films they grace, whereas both Camus and Tim will often become familiar with a score even before they see the movie. I rarely do this, as I like to experience a score for the first time in the context in which it was intended to be heard. There is one very notable exception.

Back in film school I was still in the thrall of the punk explosion and my musical tastes were narrow, but I had friends with an appreciation of a wider range of music who helped me to break out of that bubble. One of them had a real thing for the distinctive sound of a musician named Ry Cooder, whose guitar work I liked but whose voice I was not sold on (that's since changed, I have to say). One day, my friend showed up at the door of the editing room in which I was a virtual prisoner with a new Cooder album and a record player borrowed from the AV department. "You've got to hear this," he assured me, his eyes wide with enthusiasm. It was the soundtrack to an as-yet to be released film called The Long Riders. And it was superb, a seductive collection of music and songs that felt astonishingly authentic to the period in which the film was set, right down to the instruments used to perform it. You have to understand that we were already big fans of westerns and their scores and that the stirring title theme from John Ford's The Horse Soldiers was our favourite drinking song (you can watch and listen to it and sing along here), but we listened to that Cooder LP so many times over the subsequent weeks that our drunken revelries were cheered on instead by a rousing chorus of "I'm a Good Old Rebel".

The course had finished and the two of us had gone our separate ways by the time the film was released in the UK, but it didn't disappoint, except for one small thing. It's here that I first discovered one of the perils of becoming addicted to a soundtrack before you see the film it was written for: just occasionally it contains material that didn't make it into the film or that was created solely for the soundtrack album. The one here was something special, as an old ex-confederate soldier, played by John Ford regular actor Harry Carey Jnr. (who has a small but memorable role in the film), defiantly recalls what his grandfather had told him about Jesse James, backed by a gentle and soulful banjo. And it's not in the film! Noooooo! One more good reason to get your hands on the soundtrack, then.

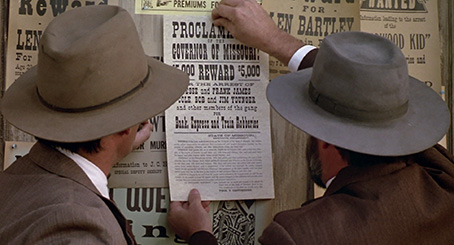

The Long Riders tells the story of the James-Younger gang, perhaps the most notorious band of outlaws to grace the post-civil war American West. This is hardly new territory for the American western – Wikipedia lists almost thirty feature films in which Jesse James features, often as the title character. He was frequently romanticised as a Robin Hood-like outlaw, an image that was memorably turned on its head by Phil Kaufman's 1972 The Great Northfield Minnesota Raid, where Robert Duvall portrayed him as an unpredictable and potentially lethal eccentric.

The Long Riders assumes from the opening scene that you don't need to be told who Jesse James is or what he does for a living. It certainly wastes no time on introductory build-up, opening midway through a bank robbery at a point in the gang's history when they have already achieved countrywide notoriety. At this point the gang consisted of Jesse and Frank James, Cole, Jim and Bob Younger, and Clell and Ed Miller (the actual gang was larger and its make-up would vary on a job-by-job basis), though Ed is quickly given the boot here when he kills a cashier for no good reason.*

What unfolds is more a potted history than a biographical portrait, a series of indirectly linked sequences covering the period from when the gang's notoriety was at its peak through to the fateful attempt to rob the First National Bank in Northfield, Minnesota, and Jesse's assassination at the hands of Bob and Charlie Ford. Unusually, the film is as interested in the personalities and social lives of the gang members as the deeds that made them famous and gives almost equal screen time to each of them – here Jesse is not the dominant or central character, but one member of a lively and engaging ensemble.

A principal reason for why this works as well as it does lies in a unique approach to casting that a few too many reviewers dismissed as a gimmick on the film's initial release, that of the casting of real acting brothers in the roles of the outlaw siblings. Jesse and Frank James are played by James and Stacey Keach, Cole, Jim and Bob Younger by David, Keith and Robert Carradine, Ed and Clell Miller by Dennis and Randy Quaid, and Charlie and Bob Ford by Christopher and Nicholas Guest. Take a look at those names and ponder for a second on their collective body of work and tell me this is a gimmick. Every one of them is on excellent form here, but it's Keith and a sublimely laid-back David Carradine who make the biggest impression,** though both are given a run for their money by an impeccably low-key turn from Stacey Keach as Frank James, who more than anyone here feels like a man who really has stepped out of the old West. There's some impressive work in the supporting roles, too, notably Pamela Reed as world-weary prostitute Belle Starr, James Remar as her fiery Cherokee husband Sam Starr, and a lovely turn from the aforementioned Harry Carey Jnr. as a proud former Confederate soldier who ends up siding with the gang when they rob the stagecoach on which he is travelling.

Initiated by James and Stacey Keach, the project eventually fell under the guiding hand of Walter Hill, fresh from the international success of The Warriors and here able to express his admiration and kinship for the cinema of Sam Peckinpah (for whom he wrote The Getaway), particularly in the tone and the handling of the gunplay. This is first evident in the use of slow-motion and cross-cutting in the revenge killing of two of the Pinkerton men responsible for the death of Jesse's younger half-brother Archie, but is given full reign in the brilliantly handled climactic Northfield Minnesota raid. This is a genuinely show-stopping sequence in which slow-motion visuals, distorted animalistic sound effects and Freeman Davies and David Holden's precision editing create an electrifying sense of the destructive mayhem that was unleashed on the unsuspecting gang, while the high-pitched whine of approaching bullets and the violence of their impact really bring home the effect of every gunshot on those caught in the crossfire.

The Long Riders was a film that both cemented Walter Hill's reputation as a director of stylish but thoughtful action movies and marked what seemed at the time like a change of direction, an abandonment of the comic-book overtones that characterised and charged The Warriors in favour of a grittier, more realistic approach to action and myth-making, one influenced by Peckinpah but that understood that there was so much more to what distinguished that unique filmmaker's work than slow-motion blood letting. Although speculative in its handling of the personal scenes (the look of the film may be strikingly realistic, but the dialogue is unquestionably modern in is smartness and wit), many of the portrayed events are based on recorded fact, and Hill strikes a fine balance between the seemingly opposing elements of fact and fiction by allowing the former to guide and inform the latter. It's this that makes the character-based scenes so unexpectedly captivating and appropriately so, as unlike many a western outlaw, these were men for whom family life was paramount and whose activities were driven as much by the South's Civil War defeat as the intent to support their families by whatever means. It's in these scenes that the advantage of casting real brothers is most evident, where whole conversations are compressed into a single exchange of looks and that easy camaraderie that only true siblings seem to share.

Which brings me back to the very thing that first drew me to the film in the first place, Ry Cooder's sublime music, which is beautifully integrated into the fabric of the film, but not in the manner of a traditional score. Much of the music here is diegetic, played by visible musicians in bars and at social events; there are almost no traditional cues, and on the rare occasions that the music does underscore the drama, it serves the mood rather than the action, sometimes hauntingly so.

It's a film whose lack of formal narrative prompts specific scenes, exchanges and set-pieces to register, and The Long Riders is littered with them, effortlessly priceless moments that occasionally linger due to a duality of meaning in the context in which they are delivered. One of my favourites is almost throwaway in nature but resonates throughout the scenes that follow. As the gang travel by train to Northfield, Minnesota, Cole light-heartedly suggests to Frank that he is thinking of writing a book about his exploits "as a gentleman and a lover." "I expect a free copy", Frank tells him, to which an amused Cole replies, as if commenting on both this request and the consequences of their chosen lifestyle, "You gotta pay, Frank. You gotta pay."

My excitement at the prospect of seeing a film as visually arresting as The Long Riders on Blu-ray was tempered a little by the very first image of the opening title sequence, a wide shot of a Minnesota plain (actually Georgia, but that's beside the point) in which none of the detail on the grassy hill that almost fills the screen is sharp. The shots that immediately follow are similarly uninspiring, and I would normally put this down to the photochemical process used to put titles on film in these pre-digital days, but the truth is that this opening image is actually sharper on the previously released United Artists DVD. Fortunately, things improve substantially when the action proper begins – the close-up of the cashier's hands removing the money from the cash drawer is noticeably sharper and tonally richer on the Blu-ray, and the shots that follow have a vibrancy and crispness lacking on the muddier-looking DVD transfer. The difference is clearly visible in the scene in which the gang dispense with Ed Miller – on the close-up of Jesse when he addresses Ed, there are beads of sweat on the Blu-ray transfer that are invisible on the DVD.

Not everything is so good. In common with a few too many Blu-ray transfers of films from the 70s, the colour timing appears to have been fiddled with to over-accentuate tints used on the cinema print and earlier home video releases, with the previous sepia hue of lamp-lit wedding sequence given a more orangey makeover that frankly has a more artificial feel (and is not consistent within the scene). The contrast has also been aggressively boosted here, with black crush swallowing some picture detail and highlights burned out, which is particularly unattractive when faces are involved. Other scenes are similarly affected to a lesser degree, but this is by no means consistent, with daylight exteriors often close to excellent (there is still some black crush here in places). Pleasingly, the Northfield Minnesota raid is one of the best-looking scenes in the film.

The linear PCM stereo track is very clear and showcases the sound effects and Cooder's music score well. The bass rumbles underscoring the final stages of the raid sequence are rather nicely handled, given that the subwoofer has not been invited to the party.

Surprisingly (and disappointingly), there are no subtitle options.

Outlaw Brothers: The Making of The Long Riders (60:51)

Director Walter Hill, actor, writer and producer James Keach and actor Robert Carradine look back at the making of the film in considerable detail (check the running time), outlining how the project came about, recalling stories of the shoot, and discussing how they approached making what both Keach and Hill describe as "a Mid-Western" about a man who has already been immortalised so many times on film. And it's enthralling stuff, divided into chapters (that for some reason do not have chapter stops) that cover the genesis of the project, the historical facts, having brothers played by brothers, the look of the film, Harry Carey Jnr., the knife fight between Cole Younger and Sam Starr (Hill tells a lovely story of how a visit from Sam Fuller prompted everyone to up their game on this), the horsemanship skills of the actors, the music ("A lot of people say it's better than the movie," says Hill with a wry smile, "and they may well be right"), what happened to the gang members in later life, and the film's Cannes screening. The lack of input from other members of the cast does initially make itself felt, but given that most have gone on to have successful film careers (at the time the film was made, David Carradine was the biggest name in the cast), their absence is not really that surprising, and Hill, Keach and Carradine do a stand-up job in their absence.

The Northfield Minnesota Raid: Anatomy of a Scene (15:30)

Hill, Keach and Carradine recall the shooting and structure of the climactic Northfield Minnesota raid sequence. Areas covered include the real-life raid, the casting of Eddie Bunker in a support role (a real bank robber playing a historical bank robber), the bullet wounds, the sound design and paying visual homage to Sam Peckinpah. The ride through the store window is covered in some detail, detailing how the horses were prepared for a stunt they would normally shy away from doing, and Hill describes the scene as being one of karmic debt in which the gang pay the price for their previous sins.

Slow Motion: Walter Hill on Sam Peckinpah (6:17)

Hill briefly discusses the difference between how he and Peckinpah (whom he describes as one of his great heroes) used slow motion and recalls working with him on The Getaway.

One of the few genuinely great modern westerns (whether younger readers will count a film made in 1980 as modern is another thing), The Long Riders really has stood the test of time well. Hill's assured direction, Ry Cooder's gorgeous period score and a string of fine performances from a cast to die for make this one of the best and most authentic takes on the story of the James-Younger gang, and the Northfield raid finale remains one of the action scene highlights of Hill's career. Second Sight's Blu-ray is a bit of a mixed bag, with a transfer that shines when the conditions are right but that stumbles elsewhere, though on the whole is still a noticeable improvement on the previous DVD. The extra features – particularly the making-of documentary – are definitely worth having.

* As it happens, it was the murder of a cashier during the robbery of the Daviess County Savings Association in Gallatin, Missouri in 1869 that first catapulted Jesse James to outlaw notoriety.

** Apparently when David Carradine was told that he stole the film, his response was "I didn't steal it, I won it fair and square."

|