Part

1: The Preamble – Where Your Nightmares End |

"All

the nightmares came today, and it looks as though

they're here to stay." |

David

Bowie – Oh! You Pretty Things |

For

every film fan, every would-be film-maker, there are cinematic

experiences that are genuinely life-changing. They tend

to come early on in our love-affair with film, when we

get our first glimpses of what lies beyond the fare offered

by the local cinemas or TV. Of course,

I'm talking about a time when we did not have access to

films on video, DVD or specialist satellite movie channels,

when to see a non-mainstream movie usually meant travelling

to the nearest big city and hunting out the film clubs and independent

cinemas.

I

was at film school when I first began to really expand

my experience of the true possibilities offered by cinema.

I was lucky in this respect – the school itself screened

a variety of films as part of a once-a-week evening class

that only four of us ever attended, which ranged from works by acknowledged masters like Josef von Sternberg

to the extremes of experimental cinema. In addition, there was

an Art Centre cinema just a short train ride away, at which

splendid double-bills would regularly play, and in the holidays

I worked in London just ten minutes walk from the National

Film Theatre, enabling me to pop in after work and catch

whatever was playing. Cinematically speaking, these were amazing times.

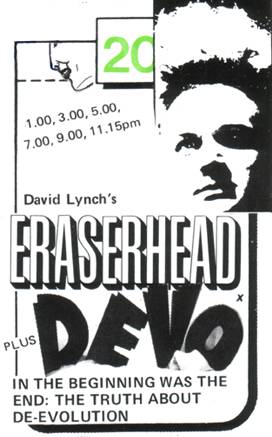

But

my favourite London film hangout was always The Scala cinema,

and that's back in the days when it was in Tottenham Street,

before it was relocated to Kings Cross after their building

was taken over by the newly launched Channel 4. The Scala

ran different double-bills every day, GREAT double-bills,

with the emphasis on cult cinema from the present and

past. Just occasionally, they would put the double features

on hold to run a single film for a several days in a row,

or in exceptional cases for a few weeks. Which brings us nicely

to Eraserhead.

I

have to admit was intrigued from the moment I heard that title. I mean,

Taxi Driver at least gave you a clue what to expect,

but what the hell did Eraserhead mean?

Words started appearing in reviews, words like 'surreal'

and 'nightmare' and 'original'. And then there were the

images, black-and-white promotional stills

that looked like no other I'd ever laid eyes on. Discussions

were taking place about the notorious 'baby', about the woman

who sang from inside a radiator, about the lead character's

electric shock hairdo. But for a film that clearly leaned

towards the experimental, it was prompting some unexpected

responses. The populist Films Illustrated, for

example, really liked it. The more highbrow Films

& Filming, however, did not. It was only the following

month, when the same Film a& Filming reviewer was laying into Phantasm (another favourite of mine),

that he confessed that his hostility towards Eraserhead

was due in no small part to his discomfort at the idea

of someone digging around in his nightmares and throwing

them up on screen. Now I was really hooked.

The

following weekend, I went off to London and bought my ticket

and descended into the darkness. The Scala was like that

in those golden days – the cinema was in the basement

and at its rear was a corridor that led to a café-bar,

a corridor with a window on its wall that allowed you to

catch a glimpse of the film that was playing before you

went in to watch it. Catching even a few frames of Eraserhead

would stop you in your tracks, but still not prepare you

for what was to follow.

You

have to remember that back when it was first shown there

was little to prepare the viewer for what they

were about to experience. Those coming to the film from

a modern perspective have Lynch's subsequent work to train

themselves up on (start at The Elephant Man

and it's sinister dream sequences, trip through Twin

Peaks, immerse yourself in Blue

Velvet and try to get your head round Lost

Highway and you'll be about ready). Back in 1979,

when the film hit the UK, we had only the back-catalogues

of Luis Buñuel and Lindsay Anderson to work from,

and both directors were by then in their twilight years

– Buñuel had already made his final film, Cet

obscur objet du désir, and Anderson was

just three years away from his last major flirt with social surrealism

in Britainnia Hospital. To really get

yourself in the mood you had to go right back to 1928

and Buñuel and Dali's seminal surrealist short, Un

Chien Andalou. I was very familiar with that

film, but I was still thoroughly caught out by Eraserhead.

I

remember emerging from the Scala basement in a daze and

being disproportionately relieved to discover that the real world was still bathed in daylight. But even before I reached the

front door I'd done an about-face and was back at the

box office to ask how much longer the film was screening

for. I knew I couldn't wait a week, so skipped some classes

and made my way back to London a few days later, and again

a few days after that. It was all I could talk about,

to the extent that the very mention of the word 'Eraserhead'

would prompt instant groans from even my closest and most

tolerant friends.

|

I

eventually convinced the manager of the local Arts Centre

cinema that he should run it for a week and cajoled everyone I knew into going to see it. This is the fatal flaw

of any obsession – so caught up was I in the film's dark spell that

I had utterly failed to realise what later seemed obvious,

that a film such as this was always going to divide opinion and might even prompt genuinely hostile reactions.

I was to learn that lesson repeatedly in the week

the film had its local screening, during which I was called

several names, had angry judgements

made about my taste in film, plus a few sincere enquiries

about my mental health. One of my fellow

students felt physically ill after the screening, only

to open his fridge when he got home to find that his flatmate

had laid out the ingredients for a rabbit stew.

You'd be amazed how much a skinned rabbit looks like the Eraserhead baby. It was three days before

he ate another meal. One of my lecturers told me that

he didn't know if it was the best film he had ever seen

or the worst. It was, he freely acknowledged, a brilliantly

made work, but he did not believe any film should have such

a bleak view of the world. Remember

that comment, I'll be coming back to it. Perhaps most

painful for someone so positively affected by the film

were the two screenings I attended that prompted outraged

vocal reactions from the audience – I mean, some people hated it, and with a passion that genuinely rattled

me. One particularly pissed-off woman emerged from the

cinema to be greeted by her children, who had found other

things to do while mummy went to see a film that was accurately

but unhelpfully described on the poster as 'the most original

horror movie in years'. "Was it good?" they

asked. "No!" she spat back, "It was AWFUL!"

But

here and there I began encountering people who, when you

mentioned the title, would widen their eyes, let their

jaw drop a little and lean forward to kick off a discussion

that could go on for hours. This is the very essence of

cult cinema, a film that develops a passionate following

in spite of box-office performance or the disdain of the

many. A few years later I took a friend who had been bowled

over by Lynch's most unexpected second feature, The

Elephant Man, to see it.* At the film's conclusion

he fell of his seat, stared wildly at the ceiling and

screamed, "Has it gone away yet??" That very

afternoon he was sitting at home with a wooden board and a large

lump of clay, making a model of the Eraserhead

baby. The cult had grown again, just a bit. Over time

it would continue to do so and turn up in the most unexpected

places, as a lyric on a song by The Clash, as an insult from a

cop in House Party, on a t-shirt in a music video by Cabaret Voltaire, and so on. It has found fans both

expected and surprising, with John Waters actively promoting

it on its release and Stanley Kubrick once inviting some

representatives from Lucas Films back to his house to watch it, describing

it at the time as his favourite film.

It remains as divisive a movie as it ever was, but also,

I would submit, as original and exciting as when it first

screened, in part because no other bugger has ever tried

to emulate it. Even Lynch himself has never again gone

this deep into the avant garde, at least in feature form,

although Lost Highway certainly swims

in similar waters and his one-minute contribution to

the 1996 Lumière and Company is

even more abstract and every bit as artistically thrilling.

But

what's that? You haven't seen Eraserhead?

You've never heard of it? Well in either case, it's time

you were introduced to the dark, bizarre world of Henry

Spencer...