| |

"Got me a movie – I want you to know

Slicing up eyeballs – I want you to know

Girlie so groovy – I want you to know

Don't know about you

But I am un Chien Andalusia" |

| |

Debaser – The Pixies |

"Nothing

in this film symbolises anything!" Luis Buñuel

and painter Salvador Dali once claimed in an attempt

to silence the various critical readings of their first

and most notorious film, Un Chien Andalou, made back in 1929 when cinema itself was in its

infancy. You can certainly appreciate where they were

coming from. Constructed largely from from dream imagery,

without regard for narrative or character, it remains

the purest cinematic expression of the spirit of surrealism,

a celluloid representation Andre Breton's definition of the movement as a chance meeting

of a sewing-machine and an umbrella on a dissecting

table. But given the interpretive aspect of dreams

themselves and the heavy Freudianism of much of Dali's

own artwork, it is inevitable that the film would be

the subject of so much study and that successive generations

of writers would attempt to join the Freudian dots.

Which has always seemed to me to be missing the point.

For many devotees of surrealist cinema it is precisely

the disconnected, seemingly random nature of Un Chien Andalou that makes it such a thrilling and revolutionary work.

This is the godfather of surrealist cinema, and without

it later directors such as Lindsay Anderson, David Lynch

and, yes, even Buñuel himself, would not have

been able to make their mark in such distinctive fashion.

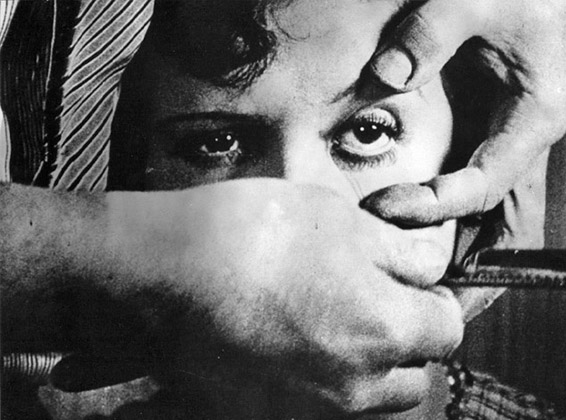

Un

Chien Andalou has, of course, the single most shocking opening sequence

in cinema history. As an Argentinean tango dances

on the soundtrack, a man – actually Buñuel himself

– sharpens a straight razor and steps out onto a balcony

to look at the night sky. Once back inside, he holds open

the eye of a young girl and, as a cloud passes in front

of the moon, slices her eyeball open in horrible, graphic

close-up. It remains a seriously jarring image to this

day, in part because it's clearly a real eyeball being cut (though

that of a dead donkey rather than a live human) and

in part because the obvious age of the film makes the

inclusion of such a sequence, at least for the uninitiated,

completely unthinkable. Imagine what it must have been like to

catch it back in 1928. There seems little doubt that

this was placed up front with the sole purpose of smacking

the audience full in the face, which it does with horrible

aplomb. Believe me, there will be few who sit through

this moment and just shrug it off, and if you have a

thing about eyes, as everyone here at Outsider seems to have,

then no matter how many times you see it, you wince.

Nothing

in the rest of the film's sixteen minutes is quite as alarming,

but the imagery and ideas come thick and fast and make

for a film that is more authentically dream-like than

anything even Buñuel has made

since, and so much of its imagery has passed into film

legend that it has become a critical tool in itself.

Thus the opening of Sam Fuller's The Big Red

One, in which the face of a large wooden statue of

Christ crucified is seen to be crawling with ants, was

read as surrealistic on its release, reflecting as it

does both a sequence in Un Chien Andalou,

in which ants emerge from a hole in a character's

hand, and the surrealists' antagonistic attitude to religion.* Elsewhere, the connection has been more deliberate, as in

David Lynch's Blue

Velvet when Jeffrey Beaumont finds

a discarded human ear crawling with ants. Dali himself even

recalled the open eye-slicing when he created the dream sequence

for Hitchcock's Spellbound

in 1945, in which large curtains bearing a repeating

eye motif are horizontally sliced (along the line of one of

the eyes) with oversized scissors.

Un

Chien Andalou

remains a delicious, dangerous and exciting montage

of unsettling dream imagery, a Freudian assault on the senses that

repeatedly hints at narratives that never unfold, reflecting

the desire of the film-makers to create a work in which

no single scene or image can be rationally explained.

From its misleadingly playful fairy-tale opening title

card and frank celebration of sexual desire to its amusing

pot-shots at the church and wonderfully absurdist comic

moments, Un Chien Andalou is sixteen minutes of pure surrealist joy.

Funny, shocking, richly imaginative and confrontational,

this is still THE surrealist film, and possibly the

most potent example of avante-garde moving image the

cinema has ever seen.

While

Un Chien Andalou was a collaborative

work between Buñuel and Dali, L'Age D'Or

saw Dali taking something of a creative back

seat, allowing Buñuel to really find his feet as a director.

By now officially a member of the surrealist movement, Buñuel

seemed here to be spoiling for a fight. At the sixth

public screening he got one when, in a move orchestrated

by right-wing agitators, the screen was attacked and

the cinema trashed, prompting police intervention and

the banning of the film. What on earth could

prompt such an extreme reaction? What could be more

offensive than the graphic slicing of an eyeball? Well

here's a clue: some years later the film was withdrawn

from distribution by its own producer, Vicomte de Noailles,

following his conversion to Catholicism. Yep, in 1930

Buñuel did the unthinkable – he loaded his cinematic

guns and aimed them squarely at what were to become

two of his favourite targets, the bourgeoisie and the

Catholic church.

As

with Un Chien Andalou, L'Age

D'Or kicks off in deliberately misleading fashion,

with several minutes of nature documentary footage featuring

scorpions battling each other and an unfortunate

rat, while title cards inform us of their physical make-up

and anti-social nature. This seeming misdirection actually lays the foundations for much that follows,

a story of a man who rejects all aspects of the society

in which he reluctantly moves, and one with a splendid

sting in its tale.

The

pace is more sedate than that of the earlier film and

the narrative more structured, though to suggest that

it tells a story in the traditional sense would be way

off the mark. Essentially a portrait of the power and frustrations

of desire, there are plenty of well-aimed pot-shots

taken at the clergy, the family unit and middle class

values, many of which are executed with an unflinching

directness and wit that still prompts admiration and even out-loud laughter. It also openly celebrates

sexual desire and fetishism – itself a subversive move

in 1930 – with the almost uncontrollable sexual urges of the

two main characters being repeatedly frustrated, twice by the

same group of visiting Majorcans.

All of this peaks in one of the film's most

justifiably famous scenes, where the pair meet in a

corner of an ornamental garden and, with engaging clumsiness,

attempt unsuccessfully to consummate their passion,

one embrace being broken when the male half of this

duo becomes fixated on the toes of a white statue that,

on his temporary departure, his female companion effectively goes

down on. This remains one of the most erotically charged

scenes in cinema history, an open celebration of forbidden

sexual longing that would no doubt

these days have the Daily Mail in an uproar of disgusted disapproval.

As

a surrealist film it delivers on all levels, reflecting

the movement's revolutionary politics and attitude to

organised religion and continuing Un

Chien Andalou's dream-like kick against realism.

This involves a fair number of delightfully bizarre

non sequiturs – the man walking by with a rock on his head

(passing a statue of a man with a rock on its head); a title

card that announces "Sometimes on Sundays"

followed by the explosive destruction of a number of

buildings; the man kicking a violin along a street before

stamping on it and walking on – but just as many are

integrated, however strangely, into the scenes in which they sit.

Thus when the leading lady walks into her bedroom and

irritatedly shifts a cow from her bed, its absurdity feels only

a couple of steps from reality because she behaves

as if it were a disobedient dog. Her actions are recognisably

normal; it's the choice of animal that throws the

scene into the dream world.

Several

sequences foreshadow memorable scenes in later Buñuel

works, with the maid killed by a kitchen fire yet ignored

by the wealthy party-goers having its less drastic equivalent

in The Exterminating Angel, while the

gamekeeper who shoots dead his young son for playfully

snatching his father's tobacco has echoes throughout

the director's filmography, from the violent blasting

of a butterfly in Diary of a Chambermaid to the priest who calmly uses a shotgun on a man whose

last confession he has just taken in The Discreet

Charm of the Bourgeoisie.

But

it's in the final scene that Buñuel really throws

caution to the wind, to the degree that if it were made

today it would still cause an uproar. A long textual

introduction (based on De Sade's 120 Days of Sodom)

outlines the appalling depravities inflicted by "four

godless and unprincipled scoundrels" at the Château

de Selliny on "eight lovely adolescent girls,"

culminating in the introduction of their leader, the

monstrous Duc de Blangis, who is revealed to be Jesus.

Weary from the 120 day long orgy, he still has the energy

to return to the Château to finish off a girl

who survived the depravities, and in a particularly

bizarre gag, gets his beard ripped off. The final image

of a crucifix adorned with female scalps, accompanied

by jovial music, plays almost like a cheerful declaration

of war on Christianity.

If

L'Age D'Or lacks the fired-up energy

of Un Chien Andalou, it nevertheless

remains a marvelous slice of surrealist cinema, brimming

with invention and revolutionary daring and a clear

pointer to the direction Buñuel's cinema was

to take in the years to come. As cinematic companion

pieces they are virtually without peer and remain two

of the most influential, exciting and enjoyable examples

of avante garde cinema at its most ferociously effective.

Oh

well. First up, it should be recognised that both films

are over seventy years old and and finding a source

print that is even close to pristine is a bit of a no-hoper.

But given the sort of restoration work done by Eureka

on films like M and The Last

Laugh, the transfers here leave an lot to be

desired.

Un

Chien Andalou definitely comes off worst –

scratches, dust spots and other film damage are very evident

throughout, the contrast range is average and black levels

are closer to dark grey. Though much of this is undoubtedly

down to the available source print, there has clearly

been little attempt to clean this up digitally and

the transfer has picked up four small dots that appear

to have been actually added to the on-screen

distractions (you can tell they are not film damage

as they sit solidly throughout, while the film

itself is subject to some frame jitter). Perhaps most

frustratingly, the extracts of the film included in

the documentary on this disk, A Propósito

de Buñuel, are noticeably superior in

contrast, sharpness and stability. As a silent film

with music 'as directed by Luis Buñuel', the

only subtitles are those accompanying the title cards,

and these are burnt in. The music is as originally recorded

for early sound prints, complete with slight distortion

and sudden editing jumps.

L'Age

D'Or fares a little better, especially on the contrast and

black levels (the contrast does vary at times, but this

is doubtless due to the the condition of the source

print). It still has more than its share of dust spots

and film damage, though given that there was an attempt

to destroy all prints following its banning this is

at least understandable. Again no visible restoration

work appears to have been carried out, but some scenes

have survived rather well and have a pleasing look to

them, despite the damage. The sound shows its age, with

music and sound effects sometimes coming across as distorted,

but this was one of the first sound films and cannot

be expected to be crystal clear. The subtitles here

are removable and very clearly done, though have been

specifically translated for UK viewers, as can be witnessed

in the early scene with the peasant soldiers, one of

whom says to the other, "Bollocks."

Though

limited in number, the extras on offer here do at first

glance appear to be very well focused. Of course, as with

other aspects of this box set, it ain't that simple, but

one at least is first rate, so I'll save that until last.

Most of the extras revolve around Robert Short, author

of the books Dada and Surrealism and Surrealist

Cinema, and this proves something of a mixed blessing.

He certainly knows his subject, but his delivery is as

dry and overly analytical as a particularly heavy-going

university lecture.

First

up is an Introduction by Robert Short,

which runs for a most unexpected 25 minutes and consists

of a direct-to-camera address in which he discusses the background and production of the two films. Despite his delivery style,

this is actually rather interesting, packing quite a bit

of information into the running time, and despite my long-standing

love of the two films there were a few facts I was unaware

of and enjoyed hearing here (Buñuel filling his pocket

with stones for the premiere of Un Chien Andalou to throw at the audience in case of a hostile reception is a personal favourite). When I say it's interesting, I mean it's

interesting to listen to – visually it's deadly stuff,

with Short talking straight

to camera, dressed in a shiny black jacket and uninterrupted by stills or film extracts, the

mid-shot intermittently (and sometimes jarringly) jumping

to a close-up and back in an unsuccessful attempt to liven things

up. It's best to ignore the screen and listen while you're reading

the included booklet, which

really is rather nice and gives plenty of background to

the film, including film notes from Buñuel himself.

Short

also provides a commentary for

each film, though both diverge from the audio commentariy standard

in different ways. In Un Chien Andalou,

Short examines the notorious opening in detail, and in

order for him to do so the sequence is repeated, making this quite possibly the only audio commentary

that is longer than the film it accompanies.

On L'Age D'Or the reverse is true, with the film edited down to allow Short to concentrate

on key sequences only, running for just half the length

of the film. As for the content...well therin lies the

rub. While a good part of the commentary on L'Age

D'Or focuses on the construction of the scenes

under examination, the one accompanying Un Chien

Andalou over-analyses the film to such a degree

that twice I actually lost track of what Short was trying to say and my interest and patience were frequently taxed.

Sounding at times as if he's swallowed a whole set of

volumes on Freud, Short tones this down a bit on L'Age

D'Or, though still kicks off with some thematically

baffling musings on the opposing forces of gold and shit.

The

final extra, located on the Un Chien Andalou

disk, is the best by far, the Spanish/Mexican documentary

A Propósito de Buñuel.

Rather than an exhaustive study of Buñuel's cinema,

it concentrates on Buñuel the man: his childhood

in Spain, his religious education, his friendships, his

long-standing marriage to Jeanne Rucar, his seemingly

puritanical attitude to on-screen sex, his love of martinis

and his sense of humour. Of course, his films are dealt

with in some detail, but more often than not on a personal

and anecdotal level. Running a handsome 98 minutes, this

is a thoroughly enjoyable and engaging production, but

does have one surprising omission – absolutely none of

the participants are identified by name through caption

or voice-over, and though you can work who some of them

are from what is said or shown, a fair number remain frustratingly

anonymous. I'm guessing that all concerned are familiar

enough to the programme's original target audience for

this not to be an issue for them, but a little help here

would have been nice. Shot on video and framed at 1.66:1

(non-anamorphic), the transfer is first-rate, though the

quality of included film clips varies wildly. As mentioned

before, the clips from Un Chien Andalou

are actually superior to the print included on this very

disk.

Un Chien Andalou and L'Age D'Or

are the two most important works in the history of avant

garde cinema and were the founding fathers of surrealist

film. Both still have the power, over seventy bloody years

later, to shock and astound. What film now will be able

to say that so long after it's release?

It's

wonderful to see the two films released on DVD, but with

the restoration work being carried out on other important works from

this period the quality of the transfers here can't help

but feel a little disappointing. The inclusion of commentaries

is welcome, but ones that actually told you about the making

of the films rather than disappearing up an analytical rectum

would have been preferable. The inclusion of the documentary,

A Propósito de Buñuel, is

the real selling point, though I have to take issue with

the retail price of of £30, making this two-disk package

more expensive than most Criterion sets (and that includes

the cost of importing them), which almost always benefit

from extensive restoration work and a bucketload of classy

extras. Putting the whole set in a fancy, oversized box

fails to convince me – it doesn't fit on the shelf with

my other disks – and so while the films come wholeheartedly

recommended, the DVDs are probably for determined (or rich)

devotees only, unless you can find them in a sale.

|