| "I will never understand the urge people have to destroy." |

Director Peter Watkins |

As cineastes, we've doubtless all heard the phrase, "You're only as good as your last movie." That's not a statement of fact, but a reflection of attitudes in an industry whose creative talent is too often judged on their ability to deliver a film that scores box-office gold. Sure, you can wow the critics with that dynamite first film, but when a studio throws money at your second or third project and it fails to financially ignite, you'll quickly go from being the new bright young thing to persona non grata. If you remove the whole concept of box-office returns from the equation, however, there should theoretically be no reason for this narrative to play out. Yet back in the mid-60s, a new young director went in the space of a single film from an exciting new talent to a man whose work would be banned from worldwide TV transmission for twenty years. The talent in question is Peter Watkins, and the two films he made for the BBC back in 1964 and 1965 were revolutionary works that almost single-handedly redefined documentary film form. The first was a recreation of events that occurred during and following the history-changing Battle of Culloden and would launch Watkins' career, the second an exploration of the likely consequences of a nuclear attack on Britain and would come close to bringing that same career to a close. So what is it, exactly, that continues to make these two films so special?

The 1746 Battle of Culloden remains to this day one of the most ignoble events in British military history. A short but decisive battle between Jacobite forces led by Charles Edward Stuart – aka, 'Bonnie Prince Charlie' – and loyalist troops commanded by William Augustus, the Duke of Cumberland, it is chiefly remembered for disastrous mismanagement of the Stuart forces and the appalling brutality meted out to the defeated Scots by the Loyalist soldiers. Obviously there's a lot more to it than that, but I'm not about to fill a few paragraphs outlining the details of the conflict or its background here, as the information is freely available elsewhere and is usefully summarised at the start of the film by Watkins himself. If you want to know more before you sit down for the film (never a bad idea when dealing with film recreations of historical fact) then the battle's Wikipedia page should get you started.

But having laid the factual groundwork, Watkins elects not to deliver a tactical blow-by-blow account in the manner of a standard historical documentary, but to explore the impact of the battle on those caught up in the fighting on both sides. In order to do this he didn't so much make break with documentary convention as completely rewrite the book by recording events that took place in 1746 as if they were being filmed by a 1960s news camera crew. It's an approach that by rights should have fallen flat on its bold intentions, but instead brings an astonishing immediacy to an historical event that in other hands would likely have been the subject for a worthy but staid academic study. And we're not just talking about the camera technique here – right from the start Watkins establishes that there is a news camera crew on the battlefield, something clearly signalled when Jacobite officer Sir John MacDonald is introduced in voice-over, then points directly at the camera and appears to pass comment on its presence to a colleague. Individuals on both sides are interviewed by an unseen reporter and respond just as their real-world equivalent might in their situation, and when battle commences, there is a very real sense that the camera crew has also been caught up in the fighting.

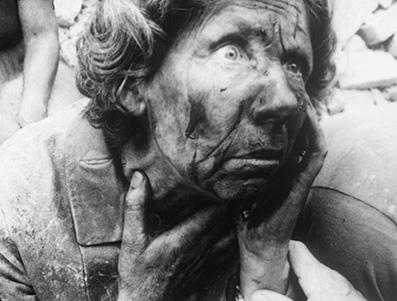

If the overuse and misuse of this faux-documentary technique in recent years – with a handheld twitchiness applied to every shot, however inappropriate – has robbed it of its 60s shock of the new, its use here is so tightly targeted and so purposeful that it still startles in its effectiveness all these years on. Indeed, the monochome 4:3 framing aside, the only concession to changing times is the fact that the interviewees speak directly into the lens, where now they would be talking to a reporter standing just off-camera. Even so, this approach has its own specific power, forcing us to look those who are about to die, or the injured who have been left on the battlefield to suffer, directly in the eye, which has the effect of personalising the experience of those ordinary soldiers and luckless clansman whose stories we do not usually get to hear. As they stare desperately, helplessly or accusingly at us, we're forced to re-examine our proxy role as media observers with neither the power or the will to intervene and somehow alter their fate, time travellers with cameras who, like the dinosaur tourists in Ray Bradbury's A Sound of Thunder, are invited to watch on but are forbidden from taking any steps that might change the course of pre-written history.

The cumulative effect is genuinely overpowering, as what begins as a seemingly even-handed look at how this decisive battle unfolded evolves seamlessly into a heartfelt and persuasive anti-war statement and a cry for the fate of the common man. The loyalist commanders – I'm reluctant to say English as the monarchy they were fighting to protect was actually German – ultimately come in for the strongest criticism, and given the shocking treatment of the defeated Highlanders I'd say this was justified, and then some. Watkins' own matter-of-fact narration is a crucial element here, outlining the treatment of the Highlanders as if reading from official reports, and introducing us to various forms of ammunition before soberly stating, "This is what it does..."

Working as he was with local amateurs and members of Canterbury's Playcraft theatre group and armed with only a single working cannon, that Watkins was able to achieve so much on a meagre £3,000 budget is genuinely remarkable. The small concessions are certainly evident, as despite some ingenious editing by Michael Bradsell and Dick Bush's frequently energised camerawork, the shortage of personnel (and uniforms, I'm guessing) ensures we never really get a clear feel for the scale of the battle, which is observed instead as a series of skirmishes, though these are so brilliantly handled that they never feel like a cheap workaround. Indeed, the filmmaking itself is so confident and technically innovative for its day that it's hard to believe this was Watkins' first professional film; he even at one point risks breaking the carefully crafted documentary spell to look through the eyes of a wounded Highlander as he is dragged across the field and put to death, a sequence whose shocking conclusion is created entirely in the camerawork and edit.

Over fifty years on, Culloden remains an astonishing achievement, one that technically stands up to any film you care to pitch against it today and whose emotional impact is as strong as it ever was. It genuinely heartened me to learn that it was enthusiastically received by critics and public alike on its first TV screening, ensuring that a rare second screening followed a short while later. Watkins was celebrated as a an exciting new talent and would likely have had his choice of future projects, yet the one that he fought for, a film that would take the ideas and techniques he had explored in Culloden and apply them to a speculative, near future event, was ultimately to bring this most promising of TV careers to a premature end.

At a time when we are increasingly encouraged to believe that everyone who even name checks Allah is a probable suicide bomber, it's easy to forget that our principal fear was once that the world was going to end in a nuclear holocaust. And this was no abstract terror, but one that a good many of us were convinced was going to play out, sooner or later. It hasn't yet, but those weapons are still out there, waiting for the right dispute between two nuclear powers to send the missiles flying and bring about the end of the world as we know it.

It's a fear that our own government – and we all trust them, right? – tried to quell with a hopeless piece of would-be reassuring bullshit called Protect and Survive, a guide to what you should do to protect yourself and your family in the event of a nuclear strike. Check out Raymond Briggs' heartbreaking graphic novel When the Wind Blows (or Jimmy T. Murakami's gut-wrenching film adaptation) for an idea of just how much use the advice in this pamphlet would actually be (how apt that revered activist E.P. Thompson's response pamphlet was titled Protest and Survive). It was a nightmare scenario whichever way you looked at it, one that was famously summed up in a quote whose origins are still the subject of speculation: "Will the living envy the dead?"

It was in this climate that Peter Watkins proposed what he originally referred to as 'The Nuclear Film'. His aim was to explore the likely effects of a nuclear attack on Britain, and as he did with Culloden, to do so from the perspective of ordinary people and in convincingly documentary fashion. The key difference was that while Culloden was a recreation of historical fact and distanced by the passing of time, The War Game was a speculation on events that had yet to unfold, and set very much in the here and now. But as with Culloden, everything portrayed in The War Game was the result of meticulous and documented research, much of which is referenced in the film itself.

What continues to make the film so shocking even fifty years after it was made is the startling immediacy of Watkins' approach and the sense that we are not watching dramatized scenes, but a genuine documentary record of events that have already taken place. As with Culloden, the use of non-professional actors pays real dividends here (even if it does saddle a few of the interviewees with very middle-class diction), as does cinematographer Peter Bartlett's authentically vérité handheld camerawork, while editor Michael Bradsell once again keeps the pace urgent and helps Watkins to suggest a real sense of the scale of the catastrophe on what was doubtless a minuscule budget. Sealing the deal is the narration by Michael Aspel and Peter Graham, whose sober delivery brings home the horror by keeping it factual and avoiding unnecessary sensation and hyperbole.

The social upheaval depicted in the build-up – the rationing of food, the forced billeting of evacuees – would likely have tapped into memories of wartime restrictions for many back in 1965, but once the bombs start flying, apprehension quickly gives way to blind terror, with the effects of nearby nuclear blast terrifyingly suggested through grabbed-on-the-run camerawork, thunderous sound effects, shaking props and the convincing panic of the naturalistic performers. But it's after the bombs have dropped that the film delivers its most devastating gut punches: the bucket full of wedding rings collected from corpses; the wide-eyed and bomb-scarred woman struggling to breathe; the execution of a small band of ordinary-looking looters; the man so traumatised that he is unable to even lift a spoonful of soup to his mouth to eat; the long track over the bodies of victims that plays almost like a grim outtake from a holocaust documentary.

The resulting film was so shocking that the very people who had commissioned it refused to screen it, or so the story goes. Others have (convincingly) argued that the pressure actually came from the government and the Ministry of Defence, but the official statement from the BBC claimed that "the effect of the film has been judged by the BBC to be too horrifying for the medium of broadcasting. It will, however, be shown to invited audiences..." Eventually, after some serious work on the furious Watkins' part, the film secured a cinema release in the UK and the US, where it won the Academy Award for Best Documentary Feature in 1966. It would not be shown on TV anywhere in the world for another twenty years, after which it received a one-off screening on the BBC to mark the fortieth anniversary of the dropping of the first atomic bomb on Hiroshima. How ironic, then, that this single appearance on British TV occurred shortly before a repeat screening of Threads, Mick Jackson's similarly horrifying look at the effects of a nuclear attack on Sheffield. It's a film that owes a huge debt to The War Game and was not only commissioned by the BBC (in conjunction with Nine Network Australia), but was featured on the front cover of Radio Times as a programming highlight and enjoyed a second uncensored screening on the very same channel the following year.

Coming back to the film after a gap of several years, I was astonished at how little it seems to have dated. Sure, it's in monochrome and framed 4:3, and in common with Culloden, the interviews are conducted straight to camera, a technique that has since fallen by the news reporting wayside. But the sheer strength of the filmmaking and the subsequent shift of focus away from nuclear war as a primary threat has ensured that The War Game still has the power to leave an audience stunned. I witnessed this a few years ago when I showed a sequence in which a family attempts to take shelter in their home following the nearby detonation of a nuclear device to a group of slightly jaded media students, and when the lights went up there was a collective exhalation of shock. It probably helped that the location in which this sequence was set was less than ten miles from where this screening took place.

The passing of time has also paid tribute to the lasting power and long reach of Watkins' extraordinary film, in the techniques he pioneered, in similarly themed films such as Threads and The Day After, and in key aspects the whole post-apocalypse sub-genre. It effectively redefined the drama-documentary sub-genre so completely that it remains virtually without peer to this day, and remains an object lesson on just how to create an authentic faux-documentary look and feel without triggering motion sickness in the viewer. It even boasts a scene that quietly drops the jaw for its technical audacity alone, a single shot sequence that follows a motorcycle courier as he drives across town, walks into a building and hands a dispatch to government ministers, a shot that so impressed award-winning cameraman turned director Haskell Wexler that he reproduced it in his 1969 Medium Cool.

The BBC's decision not to screen the film proved to be the end of a short and initially starry road for the young Peter Watkins, and he left the corporation and eventually the country, and would never work for British television again. His subsequent film career has been peppered with funding battles that have doubtless seen a number of potentially great projects consigned to the drawing board, but also gave birth to a sprinkling of dyed-in-the-wool masterpieces like Punishment Park and Edvard Munch. By virtue of their brief length and their first film status, Culloden and The War Game may lack these later films' structural sophistication and narrative complexity, but they remain to this day two of the most astonishing and important documentary films in the proud history of the medium.

| Culloden – a personal aside (feel free to skip ahead) |

|

My relationship with Culloden is a long-standing and very personal one, and you'll have to forgive (or bypass) the long-winded nature of what follows. Too young to have seen it on its first TV screenings, I discovered it while researching its director after being left reeling by The War Game, and had my interest stoked by a good friend with a keen interest in history who knew of the film but had also never managed to see it. Then again, back in these pre-DVD days, where was it screening?

A few years later I was working at a further education college, which back then had access to a county-wide library of educational films on 16mm that could be borrowed by educational establishments for no cost (a concept that would doubtless horrify the current Education Secretary). Few of the titles requested by lecturers were of interest to me, which is probably why it took me so long to look though the library's sizeable catalogue, and to my absolutely astonishment, Culloden was in there. I immediately put in a request to borrow it and informed my friend, who arranged to travel down on the day of its arrival so that we could finally see the film we had been talking and reading about for so long.

I had a colleague at the college with whom I was friends, a performing arts lecturer (and a bloody brilliant one) with a similar interest in film to me. We were always recommending titles to each other, and having booked Culloden, I casually mentioned it to him and asked him if he had heard of it. "I was in it," he responded, almost knocking me off my feet. What? It turns out that in the early to mid 60s, he was part of the very same Canterbury theatre group that Peter Watkins worked with and cast in supporting roles in the film.

When the film arrived, plastered with scratches and dirt and missing frames, it surpassed my expectations, and I took some delight in the fact that my colleague was instantly recognisable and that he even had a line of dialogue. I'd love to have talked to him about his experiences for this dual format release, but we've sadly since lost touch, and in the years that followed my first viewing of the film he seemed curiously reluctant to talk about it – once when I told him it was showing on TV, he responded with an almost dismissive, "Oh, that thing."

A couple of years later, I and the friend who had watched the film with me travelled to Inverness for a week long camping trip and took a day out to visit the Culloden battlefield and the visitor centre that now stands there. Frankly, this proved almost as sobering as watching the film, but still comes recommended for anyone wanting to learn more about this grim moment in history. Of the photos I took then, my most treasured is of my since departed friend making a small political point by standing and spitting on the Cumberland stone.

My first viewing of The War Game, by the way, was at the Scala cinema in London on a double-bill with Sidney Lumet's Fail Safe. To say that I emerged from the cinema in a state of nervous shock is an understatement of nuclear proportions.

Having first seen Culloden on a seriously damaged 16mm print and then later on cathode ray tube TV and the BFI's own earlier DVD release, I have to admit that my expectations for this new reelase actually weren't that high, and I was thus knocked out by the image quality here. The sharpness and level of detail is a testament to how good 16mm can look, and the balance of the contrast is absolutely spot-on, delivering solid blacks without punishing the shadows and no burn-out on the whites, and a lovely range of greys in between. The accompanying booklet states that there were a few instances of stubborn dirt and scuffing that could not be removed by ultrasonic cleaning, but these are rare, and the picture is for the most part very clean. On the whole, an excellent job.

The War Game has undergone a similar level of restoration and for the most part the results are equally impressive, something showcased in the aforementioned motorcycle shot and the interview material. Later, however, there is a visible drop in quality in some shots – the image is grungier and speckled with dirt and damage. This, it turns out, was a deliberate decision on Watkins part to give the post-bomb footage a damaged apperance to visually reflect the grime and hurt of these scenes, something he and editor Michael Bradsell achieved by taking the work print used for editing, roughing it up and using that as the source for these sequences rather than the original negative. The booklet points out that there is an inconsistency of quality to these shots and suggests that the laboratory conditions of 1960s BBC editing rooms at Ealing might also have been a contributory factor. Either way, the degeneration of the image quality here is true to the director's intentions, and if you judge the transfer by the best material, it's still a superb restoration and far superior to any previous print I've seen of the film.

Both films were shot on monochrome 16mm and both of the restorations here have been made from the original negatives. In the case of Culloden, the restoration team had A and B roll negatives to work from, a method of negative cutting that hides the splice points, but on The War Game had to work from a single cut negative, where – and I'm quoted the accompanying booklet here – "each shot change is prone to distortion with cement or adhesive obscuring parts of the image." It's a process I outlined in my review of Third Window's Blu-ray of A Snake of June, and while some of these joins are very visible (notably in the later 'roughed up' footage), elsewhere they fly by so quickly that I had to move through the film a frame at a time to see them.

The Linear PCM mono 2.0 soundtracks of both films have also been restored, with variable levels and sync issues corrected on both films. The inevitable dynamic range restrictions on both tracks aside, both tracks are otherwise in very solid shape, being largely free of damage and with only a trace of background hiss on some sequences.

Optional English subtitles for the deaf and hard of hearing are available for both films and for all of the extra features except the two commentaries.

Michael Bradsell interview (20:49)

Editor Michael Bradsell (whose impressive collection of film credits include The Devils, Jabberwocky, Scum, Local Hero and Henry V) recalls first meeting and teaming up with Watkins and his work on both Culloden and The War Game, which he covers in revealing detail. The fight over the banning of The War Game is also discussed, as is the process of dirtying up the post-bomb frop footage. A valuable extra.

John Cook commentary for Culloden

Together with his colleague Patrick Murphy, John Cook has been researching the films of Peter Watkins for some time, was on set for his most recent film, La Commune (Paris, 1871), and has plenty to say about Culloden and its making. And it's fascinating and frequently enlightening stuff, with discussions on the titles, Watkins' amateur film work, his early days at the BBC, the casting of locals and non-professional actors, the use of narration, the political overtones, the public and critical reaction, the use of facial close-ups and a whole lot more. The are a couple of brief gaps, but for the most part this is an excellent companion to the film.

Culloden on Location (7:44)

A seriously valuable find, this colour 8mm film footage shot by actor Don Fairservice provides an unexpected and most welcome peek behind the scenes of the filming of Culloden. The footage itself is silent, but John Cook again provides a useful commentary, clarifying what we are seeing and providing additional information on the cast and crew. I was delighted to see that the footage included a shot of my former colleague, who actually flashes a smile for the camera.

The War Game Commentary by Patrick Murphy

John Cook's colleague Patrick Murphy provides the commentary here and also covers a great deal of ground, including the largely amateur cast, the unrehearsed vox pops, the script development and changes, the charges that the film was anti-clerical (gets my vote), Watkins fears of being bombed during WW2, the change in film quality following the attack, Lilias Munro's make-up, the use of sound and a good deal more. I wasn't too surprised to learn that 'family values' campaigner and professional busybody Mary Whitehouse complained about the film's depiction of social breakdown without having seen it. Ain't that always the way?

The War Game – The Controversy (18:35)

Effectively a second commentary that plays over a compressed version of the film, here Patrick Murphy explores the origins of the project that became The War Game and the political machinations that led to its banning, all in fascinating and intermittently eye-opening detail. I particularly like the suggestion that the pro-nuclear establishment regarded the film as "an unacceptable truth."

The War Game Book

A series of high resolution scans of the book written by Watkins and based directly on The War Game. Pleasingly, the text can all be clearly read and the pages advanced manually using the remote control, giving you all the time you need to read them. Another very valuable inclusion, it's as fascinating for its layout as its content.

Booklet

The key features in this fine accompanying booklet are an essay on Culloden by David Archibald and a look at the politics of the banning of The War Game by John Cook, both of which are essential reads. Also included are credits for the films, information on the extra features, complete details of the restorations carried out on both films, and a number of quality production stills.

No fence sitting here. Culloden and The War Game are two of the most important and brilliant documentaries ever made, and here they get the treatment they have for so long deserved. The HD restorations and the special features are all superb, and this package should be considered an essential purchase. Very highly recommended.

|