|

Note: The film review below has been updated from my 2004 review

of the previous Japanese and UK DVD releases of the film.

| |

"I always think of the correlation between the decline of physicality and the modern concrete city. We live in such cities and little by little we lose this physicality that is a basic part of humanity. But if water enters into that correlation, this stimulates the growth of weeds and plants between the concrete, which in turn attract insects, and brings life into this concrete world. New life is born and whether you like it or not, this confronts you with the physicality inside yourself." |

| |

Writer-director Tsukamoto Shinya,

interviewed at midnighteye.com* |

Young telephone counsellor Rinko is trapped in a sexless marriage with older businessman Shigehiko. One day she is sent a package containing illicitly taken photographs of her masturbating, browsing the internet for sex toys and dressing in a the sort of super-short mini skirt she would never wear in public. A second set pictures is accompanied by a mobile phone, through which she is contacted by the photographer, Iguchi. He threatens to show the pictures to her husband unless she agrees to act out her private fantasies in a public location. Seemingly unaware of his wife's frustration-fuelled fantasies or her present predicament, Shigehiko has developed an OCD-like obsession with cleaning, but Iguchi also has plans for him.

Following an unexpected use of beautifully formal compositions in the 1999 Sôseiji [Gemini], A Snake of June [Tokugatsu no hebi] finds maverick director Tsukamoto Shinya back on more familiar turf, shooting in monochrome (though here with a steely blue tint) on 16mm and exploring some of his favourite themes, notably the liberation of the self and the destruction of the human body via the discomforting route of pain and humiliation. It's a theme he vividly explored in the 1995 Tokyo Fist [Tôkyô-ken], and those familiar with that film will find a number of recognisable touchstones here. Like that film, A Snake of June also features a trio of central characters comprised of one female and two males, one of whom is again played by Tsukamoto and all of whom are suppressing emotions that will be externalised through the process of disruption and manipulation by another member of this group. The difference here is that Tsukamoto is dealing with sex rather than violence, and for a portion of the audience this will change everything. Indeed, it's fair to say that many potential and actual viewers of this film will be put off or react badly to what they may well perceived as the exploitation of its lead female character. And while they have a point (I'll get to that in a minute), I can't help but suspect that some of these very same offended viewers would not have the same adverse reaction to the violence meted out in the average mainstream thriller, a too-common dual standard that allows religious moralisers to wave a flag for overseas military action but let loose screams of outrage at the merest glimpse of a nipple on prime time TV.

The film is broken up into three chapters headlined by icons representing male and female, which are melded into a unified symbol in the final section, which alone should give the alert something to chew on. It is the first half-hour that is likely to prove most troublesome for many (dare I say Western) viewers, as Tsukamoto, both as director and actor, puts Rinko through the emotional grinder, forcing her to act out what his character believes are desires that she is suppressing, so much so that it's on the verge of producing a physical change in her body.

Right from the start Tsukamoto the director bonds us to Rinko by viewing almost everything in the first chapter solely from her viewpoint, achieved in part by shooting her in sometimes uneasily intimate close-up. By the time Iguchi has her walking the street, terrified by the attention her short dress is attracting, I for one was cringing for her, and when she returns to a public toilet to change and cries with frustration, my discomfort level was upped a few more notches. And this is before she is forced to walk the streets wearing and internally positioned vibrator that her tormentor is able to trigger by remote control...

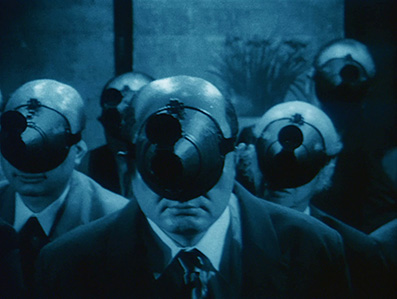

The second story is shorter and deals with her husband Shigehiko, and the narrative shifts into altogether stranger and perhaps metaphoric territory. Early in the segment Shigehiko is drugged and wakes to find himself part of an audience for what appears to be snuff theatre. Their hands manacled behind their backs, their vision restricted by conical metallic visors strapped to their face, these captive onlookers are forced to watch as a young couple are abused and then drowned before their eyes. Here Shigehiko is given a preview of is own future, both in terms of the threat to his life that lays ahead and his own masturbatory voyeurism when he follows Rinko to an orgasmic photo shoot at a deserted construction site. It's in this snuff theatre sequence that the film takes its first serious steps into the surreal, an initially startling style switch after the relatively naturalistic tone of the preceding scenes and playing almost as a bizarre melding of Terry Gilliam, David Lynch and City of Lost Children era Caro and Jeunet.

Rinko, meanwhile, turns things round on Iguchi, taking control of her own experience and coldly refusing to sympathise with her tormentor's deteriorating physical state. Increasingly Iguchi fells like a purely metaphoric figure, the trigger for Rinko's own sexual self-awareness and the discovery of her changing body condition. The punishment he metes out to Shigehiko for a selfishness that may kill his wife marks another of the film's sidesteps from reality, assaulting him with a biomechanical penile tendril that emerges from his decaying stomach. His physical existence is called into question early on in the story when a bullet aimed successfully at him by Shigehiko is revealed to have pierced nothing more than Shigehiko's own business suit, while a curious but oddly affecting moment has Iguchi placing a photographic self-portrait next to a shot taken of the room from the same angle in which he is absent – is he imagining his eventual non-existence at the hands of his cancer or inviting us to reflect on his unreality? Certainly there is an artificiality to his photographic exploits – Rinko is always fabulously lit and perfectly framed, never more so than in the alley shoot, the visual splendour of which may be the product of Rinko's fantasy.

Throughout the film Tsukamoto employs a circular motif to provide a series of links between the characters and events: the plug-holes that Shigehiko obsessively cleans; the round skylight that a bathing Rinko looks through (and through which she is presumably observed by Iguchi); the conical visors fixed to the faces of the snuff movie audience; the window on the tank in which its victims are drowned; even the logo on the drain down which the never-ending June rain pours. This is open to multiple readings, but seems to be primarily linked with the whole concept of voyeurism and gender – the camera lens, flashgun and human iris are also circular, and the circle is the only common feature of the symbols used here to represent male and female, and the only component through which they can be comfortably merged into a single icon. Water is also key, and Tsukamoto has linked the June rains in Japan with an observably increased eroticism at that time of year and to water as a reviving force. He has also admitted that water on skin was always intended to be a key aspect of the film's eroticism.

There is a great deal that could be written about this film and I've only touched on a few of the components. The wonderful thing about a work that does not lay its cards blatantly on the table is that there are so many ways to interpret what you see, and A Snake of June certainly qualifies here. Some may find it exploitative, but it has been championed elsewhere as a feminist work (the same discussion was key to any reading Takashi Miike's Audition). There seems little doubt that in spite of what he puts Rinko through, Tsukamoto intends us to squirm for her humiliation rather than be turned on by it, and to share her sense of elation when she strips off for the photo shoot that may not actually be taking place. Tsukamoto also takes a decidedly restrained approach to what he shows on screen, keeping the nudity to a minimum and repeatedly opting for suggestion when it would have been (too) easy to be confrontationally explicit.

What really sells the whole concept is Tsukamoto's typically compelling use of camera – a combination of formally composed static shots, drifting wheelchair tracks and twitchy, long-lens close-ups – and a brave and utterly committed central performance from Kurosawa Asuka. This is doubly important in a film with so few characters, especially as she has to carry the emotional weight of the film in a role that many would have shied away from (on the Happinet DVD, Kurosawa revealed that she actively pursued the part, claiming that no other role she had read allowed her to express her own feelings and personality so well). Though he has seemingly less to do, Kôtari Yuji delivers when it counts as Shigehiko, and Tsukamoto himself certainly immerses himself in the role of cancerous photographer Iguchi. And yes, that's Kitano Takeshi regular Susumu Terajima in a cameo role as the cop who accuses Shigehiko of being a peeping tom and later has his gun stolen.

A Snake of June is not an easy work or an easy sell, but over time I have become increasingly convinced of its very considerable virtues, despite initial discomfort over the presentation of its central female character and my own position as a (male) audience member and voyeur. But that's clearly the point – a female friend who watched the film was not made to feel uncomfortable by anything in it; indeed, she described the overall effect as 'liberating'.

The transfer here was, the press release informs us (I'm working from the review disc which doesn't include the box artwork, which doubtless confirms this), a new high definition transfer of the 'blue' version restored from original negatives by Tsukamoto himself. The question, of course, is which original negatives? If that sounds a strange thing to ask then know that A Snake of June was shot on 16mm monochrome film, then blown up to 35mm colour stock, at which point the film's distinctive blue tint was added, which Tsukamoto has stated took some time to get right. It thus seems likely that this tinted 35mm version was the one used for the transfer, unless Tsukamoto went back to the 16mm original and digitally retimed the colour. Adding a small layer of uncertainty is the claim by Tsukamoto in his interview below that the 16mm stock was blown up to 35mm and then transferred again to colour 35mm neg stock in order to add the colour tint. I'm also guessing that the film was shot on high-speed 16mm stock, given that a number of sequences appear to have been filmed in either available light or with minimal lighting.

With all this in mind, it would be unreasonable to expect even an HD transfer of the film to display the sort of sharpness and detail you'd get from a modern day 4K RED camera original, but brightly lit, super-crisp imagery has never really been part of the Tsukamoto aesthetic. In that respect, the difference between this new HD transfer and the one on the Happinet DVD is not quite as dramatic as you might expect, with a side-by-side comparison showing only a small increase in fine detail. But the image still feels somehow richer and crisper in many of the more strikingly lit and framed shots, the blue tone is more attractively rendered, and the contrast – which is inevitably softened by the tinting process (there are no blacks at all here, only dark blues) – is more consistent here. There are also no signs of dust, damage or compression artefacts, and there is more visioble detail in the highlights and shadows. The improvement over the more freely available (at least in the UK) standards-converted transfer on the previous Tartan DVD is more substantial.

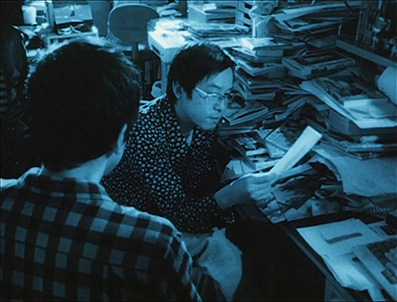

There's just one thing, something I can't ignore but intend to try and qualify. At the very bottom of frame on every edit in the film (and to a lesser extent at the very top of the frame that follows), there is what appears to be a cement splice mark, which appears as an frame-width line of uneven white bubbles. Such marks are unusual when working with film negative, the usual practice in pre-digital editing days being to create a final edit using a dual-roll method (I've done this a couple of times – it's exhausting and nerve-wracking), which has the effect of concealing the cement splices needed to join the film material together. Working with reversal film was a different story, as there was no negative to cut and no answer print to be made, and shots had to be spliced together and the joins were often visible, as anyone who started out on 8mm film will doubtless recall. I may be wrong here, but the presence of the marks does suggest that somewhere along the way either the negative or reversal material was edited this way. The fact that the marks do not appear on the transfer on the Happinet DVD initially confused me, at least until I did that side-by-side comparison (see below), when it became clear that the DVD transfer was significantly cropped on all sides, excluding the slice marks but also picture information on all four sides. It's thus safe to say that we are seeing the entire image as filmed for the very first time here. How much of a distraction this will prove to be will be down to the individual viewer; some appear not to have even noticed it (or chosen not to comment on it, a very different thing), and while I did initially find it annoying – your eyes are drawn to that part of the frame by the subtitles after all – it wasn't long before I became too caught up in the film again for it to register on anything more than a subliminal level.

The same frame from the Third Window Blu-ray (above) and the Happinet DVD (below).

Note the additional information on all sides on the Blu-ray grab. The thin sliver of

picture information below the splice line is from the frame that follows.

When talking about the soundtrack in the extra features, Tsukamoto states that this was one time when his usual mono or stereo mix would not suffice, as he wanted the audience to be surrounded by the noise of the ever-present June rain. The resulting surround mix is reproduced here as a DTS-HD 5.1 Master Audio track, and it's a glorious thing to behold. The rain really does envelop us here, boasting a clarity, spread and dynamic range that is so vibrant and evocative that it will likely have you reaching for a towel or a hat. Bass response is excellent, prompting flashguns to fire with the wallop of cannons and the bass notes of Ishikawa Chu's superb score to hit you in the chest as well as the ears. Terrific.

The optional English subtitles are very clear throughout.

Back in 2004 when I first reviewed A Snake of June, I found myself in a slight quandary when it came to which of two DVD releases to recommend to a potential UK audience. The Japanese Happinet 2-disc DVD was resplendent with extra features, but none of them had English subtitles, which rendered the interview material – which was all of interest – redundant for non-Japanese speakers. The Tartan UK disc, on the other hand, had only a trailer. What I really wanted was a UK release that included all or some of the extra features from the Happinet disc, but I'm fully aware that the cost of having extra features – which not all will watch and that most will view only once – translated and subtitled would have presented a drain on the resources of an independent distributor like the sorely missed Tartan. Happily this new Third Window Blu-ray puts all that right, importing and subtitling the most comprehensive of the extra features from the Happinet disc, and conducting a new interview with Tsukamoto that effectively fills in the gaps and expands on information supplied by that featurette. They also have included another worthwhile new special feature of their own, which is...

Commentary by Tom Mes

Long time devotee of the director's work and author of Iron Man: The Cinema of Shinya Tsukamoto (which I heartily recommend), the gentle voiced Tom Mes delivers an always interesting analysis of the film and the thinking behind it, making sure to state up front that he does not believe it is an exploitative work but one that could even be interpreted as having a feminist viewpoint (see my friend's comment above). There is some technical information – we learn that Tsukamoto always post-dubs all the sound in his films and some details about a few of the supporting players – but this is mainly a reading of the film's themes, characters and motifs, though Mes does provide a concise history of Japanese erotic cinema, then adds a serious plug for his Midnight Eye colleague Jasper Sharp's book on the subject, Behind the Pink Curtain (again, a good read).

Raining All the Time: Shinya Tsukamoto discusses 'A Snake of June'

A self-filmed and self-conducted interview in which Tsukamoto responds to a series of written questions; damned good questions, as it happens, ones that prompt a whole string of detailed and informative replies from Tsukamoto. Areas covered include his earliest encounters with manufactured erotica, the thinking behind the film's title, how and why his attitude to women has changed over the years, why he casts himself in key roles in his films, the selection of the aspect ratio and the colour tint and the technical process of making it happen, the advantages of not being part of the studio system, and a good deal more. An excellent companion to the film.

Shooting A Snake of June

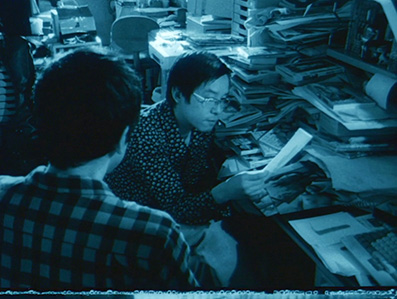

If you're going to import just one extra feature from the 2003 Happinet DVD, then this is the one to go for. Built around interviews with Tsukamoto and a good many of his collaborators, it's a comprehensive and detailed look at the making of the film that addresses a good many of the key questions you're likely to have about the production. Tsukamoto talks about the origins of the film, the reason for the blue tint, the aspect ratio, and his collaboration with composer Ishikawa Chu ("Chu doesn't fulfil the request, he surpasses it"). Associate producer Kawahara Shinichi outlines the process of transferring 16mm monochrome to 35mm colour stock, while technical specifics are provided by colour timer Oomi Masaharu. Chief photography assistant Shida Takayuki details how he disassembled a Canon Scoopic 16mm camera in an attempt to rig it to produce Tsukamoto's originally preferred square frame. Special effects supervisor Nakamura Hajime talks about creating the rain effects (which I remember being originally delighted to discover were achieved not with Hollywood style rain machines, but technicians spraying hoses in the air), which lighting supervisor Yoshida Keisuke discusses the problem of making visible using plausible backlighting. Sound effects creator Kitada Masaya discusses producing the rain that is so important to the soundtrack and suggests that if Tsukamoto – whom he believes is an artist – could manipulate sounds and notes, then he'd create the sound effects himself. Composer Ishikawa Chu recalls his initial problems writing the score, and is observed creating his unique brand of music in his studio. This is all illustrated by behind-the-scenes stills and a brief bit of on-set footage. A terrific inclusion.

Trailer

A nicely assembled trailer that gives a surprisingly good idea of the sort of thing you're in for without spelling out the specifics. It's also in the correct aspect ratio, something the ones on the Happinet DVD are not. A couple of those splice marks are also visible here.

Tsukamoto's films are always as rewarding as they are challenging and A Snake of June is no exception. Visually harking back to the steely monochrome and Academy frame of his breakthrough film Tetsuo, it continues and develops the female-centric storytelling from Sôseiji and more directly explores an eroticism only touched on in his previous works. Confrontational, compelling and artistically thrilling, it looks as good as its production process will likely allow and boasts a choice collection of special features that really do compliment the film well. Splice marks aside, it's another splendid Tsukamoto restoration and another must-have for devotes of the director's work, or frankly anyone with a taste for outsider cinema in all of its wonderfully twisted guises.

* http://www.midnighteye.com/interviews/shinya-tsukamoto/

The Japanese convention of surname first has been used throughout this review, except when use otherwise on titled extras or referenced works.

|