"All words are lies. Pain doesn't lie." |

Asami |

A few years ago, I sat down with a female friend, one with a fondness for what now defunct British distributor Tartan used to call Asian Extreme cinema, and between us we attempted to decide whether films that portrayed women as vengeful castrators – and I'm talking castration in its metaphoric sense here – were hateful expressions of a redundant male fear of female empowerment, or a righteously reactive response to years of abuse and inequality that too often cast women as viable and even willing victims of male aggression. As you might expect, the debate never reached a satisfactory conclusion. There are, after all, occasions when we are encouraged to root for the woman in a quest for revenge, usually for a violent and sexually orientated crime committed against her (the so-called rape-revenge sub-genre). Funny how men rarely suffer the same level of sexual violence in films before it is deemed they are entitled to balance the books with lethal intent. Then again, almost all of these films are made by men. Hmmm.

The other more common (and more favoured by mainstream cinema) portrayal of a vengeful woman is a mentally unstable harpy who blows a casual fling way out of proportion and becomes a dangerous threat to the life and family of the man who dumped her after she began getting a bit too serious for his insensitive, sex-on-the-side liking. And we're then supposed to root for the self-centred git who tipped her over the edge in the first place, not because he's a decent bloke at heart, but because the woman is a dangerously clingy and unreasonable monster in human form. Fatal Attraction my arse. What my friend and I did agree on was that pitting a female aggressor against a seemingly sturdy male was a solid enough premise, in part because it turned traditional notions of strength and masculinity on their heads by default. And these are not abstract concepts. Relationships do fail for a variety of reasons, and over the years two male friends of mine have found themselves at the sharp end of some pretty damned scary behaviour on the part of female ex-partners. But it's a difficult balancing act to make this work in a movie if you are to avoid a justifiably targeted misogyny bullet.

What prompted this discussion in the first place were our independent first viewings of the 1999 Japanese film Audition. Those who've seen it should have a good idea why. Surprisingly, perhaps, I was the one concerned that the film might be misogynistic, while my female friend had no such doubts. For her it was a radical feminist statement that sent a very clear message to men who believe that they should be able to use women as they please and not have to suffer the potential consequences. In case you were wondering, the two of us never dated.

Audition is a film I'd seriously suggest that newcomers first experience with no foreknowledge of what is to come. If you do fancy giving that a go then I'd bail out here, as any detailed discussion on the film is inevitably going to be littered with spoilers. That said, this is a film whose reputation precedes it, which can be a bit of a handicap, as those coming to it for the content that sent audience members scurrying will likely be caught out by the first hour of touching relationship drama. If you start watching the film on the basis of this element, however, and you're likely to be left traumatised well before the end. The description quoted by Joe Cornish in the sleeve notes of Tartan's Collector's Edition DVD described it as "a romantic drama for the first hour then you get plunged into hell." And if that sounds a little extreme, know that this climactic scene had hardened horror fan Mark Kermode hiding behind his seat at its first festival screening.

As many will now know, Audition is the film that really brought director Miike Takashi to worldwide attention. An insanely prolific filmmaker – Audition was one of five Miike directed feature films released in 1999 (when he also helmed a TV mini-series) – he had made his mark on home turf four years earlier with his feature debut, Shinjuku Triad Society, but had been directing straight-to-video features since 1991. He had already built a reputation for pushing the envelope when it came to extreme content, but few of us had seen his earlier work when Audition arrived on UK and American shores and few were prepared for what Miike delivered. If it seems to newcomers (are you still here?) that I'm still dancing round the point it's because I'm giving you a last chance to stop reading and seek out the film instead. Seriously, if you've never seen it then close this page now and go see it before proceeding, that is unless you've heard enough about it to know you'll never be able to actually sit through it.

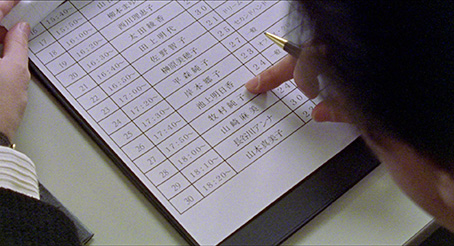

But I'm getting ahead of myself. Audition, as suggested by that Joe Cornish quote, starts in deceptively gentle fashion as a straight-up drama. Seven years after the death of his wife, small business owner Aoyama still lives alone with his now 17-year-old son Shigehiko, who one evening tells his father that he's looking worn out and that it may be time to consider marrying again. In the hope of finding a woman to whom he'd be perfectly matched, Aoyama accepts an offer from his film producer friend Yoshikawa to arrange an audition for a female lead for a romantic drama, which Aoyama could then use to vet a string of unsuspecting female hopefuls as candidates for future romantic involvement and possible marriage. Initially overwhelmed by the sheer volume of candidates, Aoyama is drawn to a young woman named Asami by the honesty of emotional depth of her résumé. After the audition Aoyama gives her a call and the two meet for a meal and seem to hit it off, but Yoshikawa cautions his friend not to rush in headlong. Something, he believes, is not quite right about this quietly spoken and polite young girl.

Something is not quite right. That, as they say, is quite an understatement. Viewed in retrospect, the decision to play the film as a thoughtful study of loneliness and gently evolving romance before any seeds of concern really start to sprout was a genuine masterstroke. Not only does this function as effective misdirection for the unwary viewer – when you're an hour in to such an evenly toned film, the last thing you expect is a stark change of direction – but also allows us to bond with our leading man completely enough for the dark events to come to hit home on an almost personal level. The effect is heightened by the easy naturalism of the performances and the audition scene itself, a lively, witty and delightfully assembled montage that brings an upbeat comic edge to a drama that few will remember for it's sense of fun.

The switch from personal drama to nightmarish terror is nowhere near as abrupt as the film's early detractors would have you believe, and occurs instead as a series of disquieting discoveries and small signals of problems to come, most of which do not play as such the first time around but on subsequent viewings have an air of sinister foreboding. Even Yoshikawa's discovery that the man Asami names as her sponsor actually disappeared 18 months previously is plausibly deflected when Asami is subtly questioned on it by Aoyama. And while at this point Aoyama is ready to believe almost anything that Asami says, to a degree so are we, not because we have become as bewitched by her as Aoyama, but quite simply because she is the polar opposite of the standard issue movie threat. Shy and politely humble in that almost clichéd Japanese female manner, Asami has all the standard hallmarks of a victim-to-be, a helpless object of affection to be terrorised or killed in order to traumatise the male lead and prompt him into vengeful action or a bold rescue attempt. How could anyone possibly feel threatened by someone as clearly harmless and gentle as Asami?

The first real hint that something may be seriously amiss comes when Aoyama, on his more cautious friend's advice, fails to call Asami as promised, and we see her sitting on the floor of her apartment, her eyes silently on the phone before her, her position never changing over the course what may be anything from hours to days. In an inspired directorial decision, Miike at one point looks down on Asami's bowed neck and the backbone that almost seems to be trying to push its way out through her skin. Quite why this shot is so unsettling (others I watched the film with once had a very similar reaction, as does Tom Mes on the second commentary track) is hard to explain, but on later viewings it's here where the alarm bells really start to ring. A short while later when Aoyama finally gives in to his own needs and calls her, the smile that slowly creeps onto Asami's face makes you're blood run cold when you know what it implies. It's also here that Miike delivers one of the best jump-scare moments in J-horror history and clearest sign yet that the story is soon to move into far darker territory.

Which brings me to the bit that no-one who not seen the film should read and is meant as a discussion point for those who have, or something to muse on for those that have no intention of seeing it. Seriously, I'm about to deliver the mother of all spoilers. All clear? Good.

There's a question my friend and I found ourselves asking when we sat down to discuss the film all those years back, and it's this: given that you'll find more unpleasant tortures and physical violence in a fair few other films, horror or otherwise, what is it about the climax of Audition that still to this day makes it so hard to watch and sent people scurrying to the exit at screenings the world over? Part of it lies in the emotional bond we have formed with Aoyama, a likeable and genuinely sympathetic figure who we've spent a good 90 minutes in the company of by this point. Events are also seen almost exclusively from his viewpoint, which has the effect of putting us in his shoes when things take a turn for the genuinely nasty. Paralysed by a drug slipped into his whisky by Asami, he's symbolically emasculated, stripped of his (male) strength and ability to fight back and unable to even vocally protest, while the injection she administers (into his tongue!) weakens him further by heightening his sensitivity to pain. Her preparations and clothing are almost surgical in nature and the torture itself involves slowly inserting needles into vulnerable points on Aoyama's skin, a sensation that most will have experienced at one point – either through accident or medical procedure – and that few will have enjoyed. It's a process made all the more unpleasant by some subtly horrible sound effects work (try watching this sequence with headphones on...) and is capped by the amputation of the fully conscious and sensitivity-heightened Aoyama's foot, which when combined with the effects of the paralysing drug taps into a deep rooted fear that just about everyone who's had an operation will have experienced at one point or another (tales of people who've woken during surgery and been unable to alert the medical team to this fact are among the most horrible you're likely to hear).

But the killer blow is the almost childlike glee with which Asami administers her tortures, her smiling delight at the pain she is inflicting underscored by the matter-of-fact way she describes what she is doing, the now famous epitome of which is her sing-song rendition of "kiri-kiri-kiri-kiri" as she slowly twists the needles into Aoyama's flesh. The subtitles on all of the prints of the film I have seen translate the word 'kiri' as 'deeper', but a Japanese friend assures me that in this instance the word is actually onomatopoeic, being the sound made by a carpenter's tool with a pin-sharp point (also called a kiri) used for boring small holes ('kiri' can also mean 'cutting' – the term 'hara-kiri' literally means 'stomach cutting' – and drilling, neither of which offer much comfort). But the real turning point comes when she amputates Aoyama's foot with a wire saw that "cuts through bones so easily." It's here that Asami's delight at her actions hits an ecstatic peak, as she joyfully saws her way through the helpless Aoyama's ankle and then tosses the severed foot aside like a lump of waste fat from a prime meat joint. That Miike shoots this moment from outside the apartment and has the foot hit a window is a stroke of filmic genius. I'm guessing it's at this point that most of those who bailed on the film got up and walked. The brief suggestion that the whole thing is a nightmare on Aoyama's part while on a weekend away with Asami is sold rather well by the timing and length of the temporal switch, and the fact that by this point details are unfolding in increasingly disorientating non-linear fashion.

Whether all this is an expression of male fear of strong or ferociously jealous women or a radical feminist statement is still, all these years later, up for discussion. Certainly Aoyama does little within the time frame of the film to warrant the treatment meted out to him by Asami for the crimes of his gender, though he does seem to carry a small pang of guilt over a one-night stand he once had with his secretary (who still seems to dote on him, even on the eve of her impending marriage). The audition ruse itself is certainly deceptive, one that plays with the hopes of dreams of the candidates for the prime purpose of finding Aoyama a mate (the film itself is real but may never get funded). But it's a ruse that Aoyama himself was unsure of from the start ("I feel like a criminal," he whispers to Yoshikawa as the audition begins), and after making direct contact with Asami he behaves impeccably in her company, while his failure to call her as promised is actually down to pressure to hold off from a concerned and insistent Yoshikawa. When the two go away for the weekend it is the far younger Asami who makes the first move on the nervous Aoyama, and she who disappears without a word of explanation the next morning, while her demand that Aoyama love only her turns out to be unexpectedly literal, one to be made at the expense of all others, including his son or the memory of his late wife.

This question of whether Asami is a reflection of male fears (Aoyama is clearly not her first victim) or a great movie antagonist whose gender allows the filmmakers to play terrifying games with expectations and archetypes can probably only be answered by director Miike, screenwriter Tengan Daisuke (son of master filmmaker Imamura Shohei) and author of the original novel Murakami Ryû, whose own deeply unsettling film Tokyo Decadence might just help to shape your opinion on this. And despite the horrors she unleashes on Aoyama, Asami is still an unexpectedly sympathetic figure, a victim of childhood abuse who is ultimately searching for the same thing in life as the lonely Aoyama. And drastic though her methods to hang on to her loved one and punish his divided loyalties may be, are they any more extreme than the mental and physical violence meted out by psychotically possessive men to their partners on a daily basis out here in the real world? It's thus perhaps no wonder my friend found herself siding with Asami as she turned this seemingly male concept on its dangerous macho head. Either way, Audition remains a beautifully structured and executed work, an involving and thoughtful drama that evolves into masterpiece of misdirection and seat-grinding terror, one that even 27 years on has the power to have hardened horror fans wincing in anticipation and rapidly sucking air through tightly clenched teeth.

The result of a 2K restoration from the original 35mm interpositive for Arrow Films, the 1.85:1 transfer here is easily as good as I've seen the film look. Film grain is very visible for much of the film, and there are times when the sharpness feels just a little soft, but for the most part this is an excellent job, boasting very good picture detail and spot-on contrast and brightness that keeps things clear when the light levels drop (many key scenes take place in reduced light) without weakening the blacks. There's a drab look to the colour in the early scenes that was clearly intentional, as once events start to take a more sinister turn and cinematographer Yamamoto Hideo starts to experiment with lighting – as with the golden sunset hue of Aoyama's visit to the ballet school or the saturated blues of the late film flashback/hallucination clips – the colours are vividly rendered. Thousands of instances of dirt, debris and light scratches were removed during the restoration, and the result is a virtually spotless and damage-free image.

The DTS-HD Master Audio 5.1 surround soundtrack is a rich and deliciously mixed beast, the excellent clarity of the sound effects and music almost making the most of the full sound stage to deliver effective jolts and surround you with the ambient noise of locations. The dynamic range is very good here, and there are no traces of background hiss or damage.

The clearly produced English subtitles can be switched off if you want to practice your Japanese.

On the main menu rather than the extra features list is the option to play the film with an Introduction by Miike Takashi (1:15). Filmed on what looks like a DV camera on unreliable autofocus, it was shot in 2009 for what appears to be a tenth anniversary DVD release (several of the extras here have been sourced from that well). Miike comes across as very nervous here.

Commentary by Miike Takashi and Tengan Daisuke

Hosted by film writer Kobayashi Masato, this commentary featuring director Miike Takashi and screenwriter Tengan Daisuke was recorded for what sounds like an American 10th Anniversary DVD release of the film, is in Japanese with optional English subtitles (which are on by default), and is loaded with interesting stories and facts about the film and its making. Ground covered includes the process of adapting the novel, the personal takes of both men on key elements of the story, the use of real locations, the actors and performances, the impact of the film on Miike's career, the makeup effects, the Hollywood habit of remaking successful Japanese horror films, and plenty more. The lack of a supernatural element prompts neither man to class this as a horror movie ("humans are scarier than demons," Miike claims), and at one point the two wonder if anyone in America will listen to this commentary apart from Eli Roth and Quentin Tarantino.

Tom Mes Commentary

The always agreeable author of the two definitive books on the cinema of Miike Takashi delivers a typically learned and thoughtful exploration of the film's structure, technique and underlying themes. He spreads his net wider to discuss the concept and genesis of the terms J-horror and Asia Extreme, and makes a really strong case for the notion that it's possible to side with either of the main characters, even quoting from a book titled Trauma Recovery to illustrate the essential truth of Asami's extreme response to her childhood abuse. He also highlights some of the key differences between the film and the source novel, from which he also quotes, and seems to have been thrilled by the very same shots and moments from the film as I was. I'm sure we're not alone. Another excellent extra.

Interviews

Miike Takashi: Ties That Bind (30:06)

In an interview conducted specifically for this release, Miike talks about being inaccurately typecast as a director of horror and violence, the story's original author Murakami Ryû, lead actor Ishibashi Ryô and his early career as a rock star, casting former model Shiina Eihi as Asami, his approach to directing actors, and more. He admits that the film was never intended to be shown outside of Japan and that it's international release and acclaim was "an unexpected bonus," and although forward-looking, does regard the film as "one of my past treasures."

Ishibashi Ryô: Tokyo – Hollywood (16:14)

Shot for the 10th Anniversary release (as were all of the remaining interviews below), this chat with leading man Ishibashi Ryô includes details of his early career as a rock musician, his approach to character interpretation, the casting process in Japan and the notorious final scene. He believes that the film's success stems from the fact that it's "not just a horror film" and reveals that male friends have told him that watching it convinced them to never treat women badly. Job done, then.

Shiina Eihi: From Audition to Vampire Girl (20:09)

The talkative Siina Eihi, so very different to her quiet role as Asami, talks about making the move from modelling to movies, her initial nervousness at working with such experienced actors, the use of real locations, shooting the final scene, the film's overseas success and being recognised as Asami even some years after the film's release. Her take on Asami's motivations is really interesting and echoes points made by Tom Mes in his commentary, and she also touches on her later work in cult favourites Tokyo Gore Police and Vampire Girl vs. Frankenstein Girl for Nishimura Yoshihiro.

Ishibashi Renji: Miike's Toy (20:55)

Miike regular Ishibashi Renji, who describes himself as Miike's toy "made of wood or something" and Miike the filmmaker as someone who "destroys everything first, thinks about it and puts it back together." He does discuss his work as an actor, including his early work in Nikkatso Roman porno (look it up), and reveals that he has the model of his own severed head at home and that he uses it to play pranks on guests at parties. He also says of Miike, "He is strange. I hope someone can stop him." Lively and fun.

Ôsugi Ren: The Man in the Bag Speaks (16:26)

Though I've tried to give warnings about spoilers in this review, it's a little tricky when you have an extra feature with this title (this is how it appears on the Special Feature menu). Almost unrecognisable in the film, Ôsugi has worked for a number of notable Japanese directors including Sono Sion and Kitano Takeshi and also started out in Nikkatsu Roman porno. He discusses his work and his small but memorable role in Audition in particular, and claims that it's Miike's charm, passion and energy that makes people want to work with him. When making a point about his relationship with different directors, he at one point says, "I don't care how drunk Sono Sion gets..." Excuse me?

Damaged Romance: An Appreciation by Tony Rayns (35:20)

In a newly filmed interview, the venerable Mr. Rayns takes a comprehensive look at the early careers of Miike Takashi and author and filmmaker Murakami Ryû, on whose novel the film was based. His analysis of the film and its underlying themes is detailed and persuasive, making the case against it as a feminist statement on the basis of the lack of feminist thinking in Japan (though I'd argue that individual artists can still hold such views even if they are not widespread in the society in which they work). He's not the first person here to tell the story of the woman who angrily told Miike "You're sick!" after a screening at the Rotterdam Film Festival, and concludes that like so many Miike films, it presents an enigma. Fascinating stuff.

There are two trailers here. The Japanese Trailer (1:38) is prefaced by a spoiler alert on its content and is accompanied by the advice to the International Trailer (1:16) if you're looking for a taster, but even that features the film's best jump-scare and this is not something you should watch before the film.

There's also a small Gallery of production and publicity stills.

Finally, we have the expected Arrow Booklet, which includes a fine essay on the film by Anton Bitel, notes on the restoration, credits for the film and a number of stills.

Several years and a good many torture porn horror movies later, Audition still delivers a hammer blow to the senses because it allows us time to get to know the characters and paces its build-up to the final horror show with a calculation and pacing that borders on brilliance. It's the film that introduced so many of us to the eclectic cinema of Miike Takashi and despite some serious competition, is remains to this day my favourite Miike film, one of the few where there's not a thing I would want to see changed. This is the release the film has been waiting for, with a first rate transfer and an impressive soundtrack backed by a superb collection of extra features. Highly recommended. Kiri-kiri-kiri-kiri.

The Japanese convention of surname first has been used for Japanese names throughout this review.

|