|

I am not, and have never been, a romantic by nature, and am thus not naturally disposed to cinematic tales of romance. This is particularly true of its more modern incarnation, where the wit and sophistication of old-school Hollywood has been traded in for a sometimes saccharine artificiality, a teen magazine fantasy in an otherwise supposedly realistic setting. And not being a romantic, I usually need a bit more than the boy getting the girl after fate has conspired to keep them apart to provide a satisfactory narrative motivation or story conclusion. Usually. The foreknowledge that such a story is at the heart of any film inevitably prevents me from discovering the odd one (and yes, I've seen enough of the damned things to have an informed opinion on their rarity) in which the journey from the pleasures of independence to the ties of lifelong love is actually worth taking. Mind you, actually sitting me down in front of such fare is a job and a half, which is where, in the case of Whisper of the Heart, chance and an intriguing title sequence conspired to hook me in.

I've been a devotee of the animated works of Japan's Studio Ghibli since I saw my first three minute extract from one of their films many years ago (it was the cat bus sequence from Tonari no Totoro – come on, who wouldn't be hooked by that?) and have since watched and collected almost all of their output. And yet despite my enthusiasm for their style and winning way with storytelling, if you told me in advance that the main narrative thread of one of the only two Ghibli films I hadn't seen involved a tale of teenage love winning out over adversity, I'd probably still have pushed it down to the lower end of my watch list. But that's where chance gets to play its hand. Over the recent holiday period, Film Four screened a total of fifteen Ghibli animated features on a one-a-day basis, but since I have most of them on disc I wasn't that worried about catching these late afternoon screenings. Then on the fateful Friday I arrived home from work and set about clearing up the DVD-littered bomb site that used to be my living room and put the TV on to provide some background noise. Just as I did so, Whisper of the Heart began. Knowing little about it and aware that I'd be too busy to watch it properly, I reached for the remote to find less distracting material, but was stopped in my tracks by an opening sequence that completely messed with my expectations for a Ghibli film. It was not the visuals, which consisted of animated views of night-time urban life, but the fact that they were accompanied not by the expected Japanese music or song, but Olivia Newton-John singing Take Me Home, Country Roads. Eh? What on earth was this doing on the titles of a Japanese animated feature? The film had my attention, and I dropped the duster and plonked myself down in front of the TV. And once I sit down in front of a Ghibli film then the cleaning can go hang, I'm there for the duration.

The focus of the film is Shizuku, a high school student and an avid reader, a trait she doubtless inherited from her librarian father. On a visit to the school library, she discovers that every book she has borrowed has been previously read by a boy named Amasawa Seiji, whom she soon becomes intrigued by, despite never having met him. Adding to the enigma is that the only book in the library that Seiji has not borrowed before her appears to have been donated by Seiji or a member of his family. Just who is this Seiji? Surely he can't be that annoying boy who picked up the book she left on a park bench and who made fun of the song lyrics she composed for her friends?

It may not sound like much, and in narrative terms it isn't, and the relationship at the film's core develops in what probably reads like formulaic fashion – Shizuku meets a boy, finds him annoying, later discovers she quite likes him, realises who he is and then falls in love, but any hope of a relationship appears doomed due to his determination to follow his career dream. Could fate intervene and provide the happy ending she yearns for? But as so often with Ghibli, this proves to be just one component of a more layered and complex film. Indeed, Shizuku's pursuit of Seiji is never a dominant element of what plays more like a portrait of a teenage girl at a critical stage of her adolescence, a coming-of-age story that devotes equal time to her home life, her close friendship with classmate Yuko, and story threads whose purpose initially seem driven more by character than narrative. But every scene here has more than one purpose, and in a slight-of-hand way all roads lead indirectly to (and later from) Seiji.

The complications of teen relationships, for example, land Yuko a secret admirer, one she is reluctant to follow through on because of the crush she has on good-looking class jock Sugimura, who in turn has a quiet thing for the unaware Shizuku. But Shizuku is by this point too wrapped up in her fantasy of who Seiji might be to be remotely interested, and responds to Sugimura's admission with an outburst that may well point him in Yuko's direction after all (something seemingly confirmed during the end credit sequence). A delightful diversion that sees Shizuku follow a cat to a hitherto undiscovered district that overlooks the whole town, meanwhile, initially plays like an urban take on Alice's white rabbit pursuit, but it leads her to a curiosity shop run by Seiji's grandfather Nishi, a location that spellbinds Shizuku and lays the ground for a later meeting with Seiji himself. Later, Seiji's intention to travel to Italy to become a violin maker awakens in Shizuku a similar determination to test her talent as a writer, a move encouraged by Nishi and unexpectedly supported by Shizuku's quietly trusting father, one that sees her all but abandon schoolwork at a time that could have a negative impact on her future prospects.

Like Takahata Isao's 1991 Only Yesterday [Omohide poro poro] and Mochizuki Tomomi's 1993 Ocean Waves [Umi ga kikoeru], Whisper of the Heart differs from what we tend to think of as the Ghibli norm by being reality rather than fantasy based and set in a recognisable here and now. This may prompt some to wonder why they were made as animated films in the first place, but these were not stories in search of the right visual medium, but ones told by talented people for whom animation is their chosen method of artistic expression. And watch any of these films and – for reasons it's genuinely hard to pin down – you just can't imagine them working half as well as live-action features.

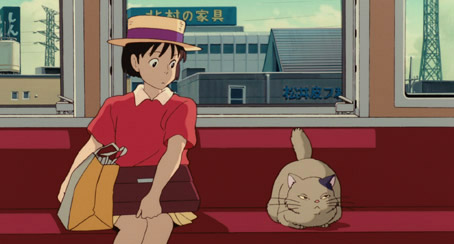

Whisper of the Heart was the first and only feature directed by former Ghibli animator Kondō Yoshifumi, who was being groomed to become of the studio's top directors and succeed founders Miyazaki Hayao and Takahata Isao as the studio head, but who died prematurely in 1998 at just 47 years of age. Whisper of the Heart provides a tantalising flavour of just what was lost and why Miyazaki and Takahata held Kondō in such high regard. The script was adapted from a manga by Hiiragi Aoi by Miyazaki himself, and Kondō clearly shares Miyazaki's fascination with small detail of human behaviour, infusing an everyday realism into the way Shizuku walks, writes, climbs or explores, and capturing the essence of the curiosity that prompts her to chase the cat across town, aided immeasurably by Nomi Yuri's multi-generic score. This fascination with small detail enlivens even throwaway moments, as when Shizuku leans over in bed to turn off the light and doesn't quite reach, so has to try a second time and reach a little further. It's the sort of chance element that happens all the time in real life but that few would even think of including in an animated work, where such small stumbles have to be planned, drawn and animated and which for most will register at only a subliminal level. The Miyazaki influence extends to the above-mentioned pursuit of the train-travelling cat* (parked next to a supervised Shizuku and peering through the train window, he looks almost like a refugee from Spirited Away), one that makes itself at home in a number of houses (each of the residents of which have given it a different name – Seiji calls him Moon) and takes deadpan pleasure from sitting just out of reach of neighbourhood dogs and teasingly dangling its tail at them. There's even a link to Miyazaki's more fantasy-based films in the visual realisations of Shizuku's story, whose backgrounds and flying islands were designed by fantasy artist Inoue Naohisa, a fan of Miyazaki's work who also provides the voice of Nishi's tall musical friend.

But it's that seemingly incongruous opening song that provides the film with its two most bewitching scenes. In the first, Shizuku shows Yuko her latest attempt at a translation (or perhaps creative interpretation) of the song's English lyrics, which the girls gently sing. It's a strangely and unexpectedly entrancing sequence, one that in just a minute of screen time establishes the importance of the song to Shizuku, her close relationship with her friend, and even her sense of humour, evident in a second version entitled 'Concrete Roads' that parodies the depersonalisation of modern cities. When she gets to sing it again later she is accompanied on the violin with virtuoso skill by Seiji, and joined midway by grandpa Nishi and two of his friends. It's a gloriously uplifting scene in which the song becomes a unifying spell, dissolving generational barriers and bonding Shizuku to Seiji in a manner that feels neither forced nor artificial. It's the first real step in the couple's realisation of their mutual attraction, one whose subsequent development is warmly but always believably handled, a winningly gentle portrait of awakening love that never stoops to the triteness of storybook romance. And it can't help but feel just a little ironic that despite being the product of a storytelling medium whose composed artificiality is a key aspect of its aesthetic, there's nothing remotely artificial about it.

I've previously mused on whether the higher resolution of Blu-ray offers any real advantages over DVD when it comes to cell-drawn animation, in which real-life shapes are simplified and colours rendered as single tones. But even visually minimalist works like Takahata Isao's My Neighbours, the Yamadas have benefitted from the HD upgrade, in the clarity of the artwork, in the smoothness of gradients, and in the lack of compression artefacts that the high storage capacity of Blu-ray allows. In the case of Laputa: Castle in the Sky, this also resulted in richer and purer colours. All of which is also true of the transfer here, which though not eye-poppingly sharp, is still crisp and detailed and with attractive though not over-saturated colour rendition. Surprisingly, there are very occasionally some compression artefacts visible on gently graduated surfaces, and four minutes in, as Shizuku muses on the library loan tickets and Seiji's name drifts off of them in line with her thoughts, there is some very visible and quite crude digital banding. But before we start blaming the transfer, it's worth noting that Whisper of the Heart was the first Ghibli film to use digital compositing, and this may well be a side-effect of that process. For the most part, though, this is a fine and attractive transfer.

Whisper of the Heart was also the first Ghibli film with a Dolby digital soundtrack, reproduced here as a DTS-HD Master Audio 5.1 surround track in both the original Japanese with optional English subtitles, or the Disney (American) English dub. Although largely front-weighted, the stereo separation is sometimes very distinctive, and there is subtle use made of the surrounds for music and ambient sound and the odd locational effect. Clarity and dynamic range are impressive in both, though the voices on the English track seem just a tad crisper than on the Japanese.

Once again I far prefer the original Japanese track to the English language dub, which transforms Shizuku into a "whatever!" American teen and makes small but still annoying alterations to the dialogue. When Seiji returns the lunch that Shizuku accidentally left at Nishi's shop, for example, Shizuku calls after him as he cycles off with Moon perched on the back of his bike. On the Japanese track, Shizuku spots Moon and calls out to Seiji "The cat! Is that your cat?" whereas on the English track she instead addresses the cat, asking, "That man. Do you know him?" The cat, as you might expect, does not respond. As so often, older voices fare better than their more localised younger counterparts, with James Sikking as Shizuku's perpetually unflappable father being the closest match to the original. Where the Japanese track really wins out over the English is when Shizuku and Yuko sing the 'Country Road' lyrics, a sequence that somehow loses its magic on the English language track. It's hardly surprising – there is, after all, no real logic to Shizuku painstakingly devising English lyrics for a song that already has English lyrics, and the Japanese girls are far better singers.

Storyboards

As is often the way with Ghibli DVDs (most of the extras here have been ported over from Optimum's earlier DVD release), the storyboards have been included for the entire film, and can be watched alongside the main feature and switched on and off using the picture-in-picture button on the remote control. Perhaps unsurprisingly, they are remarkably close to the final artwork in both their design and framing.

Background Artwork from "The Baron's Story" (4:46)

An animated slideshow to music of Inoue Naohisa's background paintings from the in-film visualisation of the story Shizuku writes and presents for Nishi to read.

Four Masterpieces from Inoue Naohisa: From Start to Finish (34:43)

The creation of four paintings by Inoue Naohisa done as slow-step time lapse and set to music. We can presume the process is accurately shown, and if so there's something intriguing about it, an abstract image from which shapes slowly emerge and become more clearly defined.

Behind the Microphone (7:59)

A standard inclusion from the American Disney release of the film that looks at the recording of the English language track and includes brief interview snippets with the performers. If you're not a fan of this track (and for the most part, I am not) then this is has a somewhat limited appeal. One of the younger female performers says "awesome" twice, and James B. Sikking, the American actor whose voice most closely matched the Japanese original, is the only lead player not shown or interviewed.

There are also 4 Japanese TV Spots (7:18), the fourth of which is longer than the three that precede it combined, plus 2 Original Japanese Trailers (2:53). There are also the usual trailers for other films in the Studio Ghibli Collection.

Ghibli does it again with this beguilingly handled and wonderfully animated and textured teen love story, the only feature from a director whose career was tragically cut short before he made a second film. If you already have the DVD then the decision to upgrade will rest largely on the picture and sound quality, both of which are fine, but if you've yet to grab it then this is a must. Warmly recommended.

* The cat in question and the feline statuette in Nishi's shop known as The Baron reappeared in Ghibli's 2002 The Cat Returns.

|