|

I have a very personal fondness for Castle in the Sky, or to give it its full title, Laputa: Castle in the Sky [Tenkû no shiro Rapyuta], a 1986 animated feature written and directed by the great Miyazaku Hayao. It's one of those rare films that have reached out of the big screen and touched me in real life, providing me with a small but memorable moment in the ersatz celebrity sun.

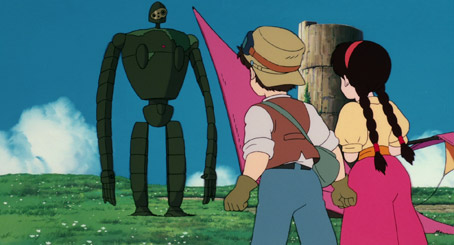

Allow me to explain. I was holidaying in Japan and was in Tokyo for a few days visiting a good friend. One day when he was tied up at his workplace (Imamura Shôhei's Japan Film Academy, as it happens) he had arranged for two of his students to take me to the Ghibli Museum in Mitaka, a wonderful place that every Studio Ghibli fan should make it their mission to visit at least once in their life. On the garden roof of the main building is a life-sized metal statue of the robot from Laputa, and sitting nearby is a scaled-down replica of one of the patterned transport cubes that appear the film's climax. Now since the film's key villain is of western appearance (as is everyone in the film if we're being honest) and wears round-cornered sunglasses, I thought it would fun for my companions if I – the only non-Japanese visitor there and armed with a similar set of specs – posed at the block for them to take a picture. No sooner had they done so than I was enthusiastically approached by a small flock of visitors, all of whom asked me to pose for their cameras and who treated me almost as if I was one of the film's stars rather than gaijin Ghibli fan-boy on a dream day out. It's a mark of the film's popularity that even eighteen years after it's initial release, and despite me getting the pose wrong and looking nothing like Muska, everyone there immediately got the reference.

Castle in the Sky begins at a gallop, as a gang of sky pirates, led by the matriarchal Dola, board a civilian airship in search of a necklace worn by orphaned young Sheeta, who is in the custody of the well-dressed but villainous Muska. In the confusion of battle Sheeta escapes her captors, climbs out of a window and clings to the ship's exterior. Pursued by both parties, she slips and plummets to what should be her death, but is saved when the stone on her necklace glows and slows her descent to a gentle drift.

In the mining town below, young engineer's assistant Pazu – also an orphan – spots the now unconscious Sheeta's descent to earth and transports her to the safety of his hilltop shack. When she wakes the next morning the pair quickly bond, but both Dola and Muska are still on Sheeta's tail but are chasing the necklace for different reasons, Dola for its probable commercial value, Muska for its magical properties. Muska believes that the necklace will guide the way to Laputa, a fabled floating castle that Pazu has also dreamed of finding since its existence was confirmed by a photograph taken by his late father. The problem for Muska is that the stone's true power can only by unleashed by Sheeta, something Pazu discovers when his attempt to mimic her slow descent sends him clattering through the roof of the building below.

The densely packed plot (the film runs for two hours but there's enough story and character development here for three) repeatedly branches off in unexpected but always satisfying directions, with Sheeta's recapture prompting Pazu to join up with Dola and her pirate gang, who soon prove to be one of the film's key delights. Their airborne attempt to rescue Steetha from Muska's fortress, where her ancestry awakens an unexpected but powerful mechanical ally, is one of the most thrillingly staged sequences in the Ghibli canon – the moment where Pazu pulls a flying machine out of a catastrophic dive in the nick of time, the force of the manoeuvre causing the water below to explode around him, has me whooping with delight every time I watch it.

Castle in the Sky is one of the most story-driven films in Miyazaki's oeuvre. Pure character scenes are few and far between, with character development effected on the fly though a bulls-eye combination of witty and economic writing, spot-on vocal performances, and the sort of winning animation and attention to small detail for which Miyazaki's work is rightly celebrated. Almost every scene helps move the story forward, often at a brisk pace and intermittently accelerating to a speed that is genuinely dizzying.

Retrospectively, it's actually hard to believe that this was the first film released under the Ghibli banner and only Miyazaki's second feature after his 1984 Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind [Kaze no tani no Naushika]. Almost all of the key elements that define what we now tend to regard as the Miyazaki style are firmly in place, from the finely tuned character humour and acrobatic energy of his child protagonists to the ageing but commanding matriarch and a fascination with unlikely but somehow strangely plausible industrial machinery – you just know that a small craft that flies by emulating the rapid beating of insect wings couldn't actually work, but watching it on screen it just seems that it should. This is an alternative reality in the steampunk mould, a fanciful variation on an industrial revolution-era Welsh mining district in which the logical co-exists with the magical and the fanciful, a place where trains travel along twisting and insanely tall wooden trestles and the townspeople are more surprised by the appearance of a car than a gargantuan airship.

The film doesn't have the thematic complexity of Miyazaki's later Spirited Away [Sen to Chihiro no kamikakushi], but then there's precious little room or need for it here. Castle in the Sky really is primarily about character and storytelling – Miyazaki stated that he wanted to create a "pure adventure," and in this respect it glows as brightly as the stone in Sheeta's necklace and sweeps you along like you're caught in the jet stream of a passing stealth fighter. Once the various parties arrive at Laputa the subtext is more visibly developed, with Muska revealing his true totalitarian colours, killing scores of the soldiers who aided his quest, then demonstrating the castle's military potential power by unleashing an army of destructive robots and triggering an atomic explosion on the ocean below. By contrast, the Castle's caretaker robots are a model of ecological friendliness, protecting the wildlife and allowing their bodies to become home to a variety of plants and animals, early signs of a philosophy that would be more fully developed in the director's later work.

The drama and comedy are in near-perfect balance and enrich the characters without ever pausing or even significantly slowing the narrative. The interaction between the pirates and their two young passengers is particularly engaging, giving rise to a touching scene in which a conversation between Pazu and Sheeta is overheard by the resting Dola (that Miyazaki stays on Dola's reaction for so long is another significant step outside of the genre's structural norm), and a morally peculiar sequence in which Sheeta becomes the target of infatuation for the all-male crew. Although played entirely for comic effect, these are adult males doting on a female child, and it's to Miyazaki's credit that there's never a sense of anything untoward in the scene, whose most striking quality is its air of innocence.

Castle in the Sky is a constant joy, a wonderfully told and textured tale that is by turns euphoric, touching, thought-provoking, funny and breathlessly exciting. The design and animation are both consistently excellent, and while not as dense in its layering as Spirited Away or as spellbindingly magical as My Neighbour Totoro [Tonari no Totoro], it's not far short on either count. It remains one of Miyazaki's most enthralling films, and if by some chance you're new to his work, then this really is a great place to start.

As with almost all of the Ghibli films released in the US, the soundtrack of Castle in the Sky has been given a Disney makeover for the American market, which has been included here alongside the original Japanese track. I've repeatedly made my case for voice tracks where the actors were selected and directed by the original filmmaker over those put together by people who were not in anyway involved in the production, and the same goes for the English language track here. As ever, the American cast prove a bit of a mixed bag. Despite being theoretically the right age to play Pazu and Sheeta, James Van Der Beek and Anna Paquin both sound considerably older than their Japanese counterparts and the characters they play, and Paquin sometimes lacks the emotional expression that the considerably older Yokozawa Keiko brings to the role. Mark Hamill and Cloris Lechman do well enough by Muska and Dola, but it's the supporting roles that tend come off best.

But the real problem here is not the American voices but the considerable changes made to Joe Hisaishi's original score. Hisaishi himself, who regularly works with Miyazaki, was commissioned to rework and expand his original thirty-nine-minute synthesiser score into a ninety-minute piece for a full orchestra, and while there's nothing wrong with the score itself, those in charge of the American dub seem determined to fill any quiet spot with music, presumably in the somewhat condescending belief that an local audience will get irritable if the sound level drops for more than a few seconds. This completely changes the tone of almost every scene, and ends up playing like an idiots' guide to emotional response, providing cues for the audience on how to react to pretty much everything (feel happy here, get tense here, oh look – it's beautiful!) and playing havoc with the film's carefully judged use of ambient sound and silence. This is most starkly illustrated when Pazu and Sheeta first enter the storm cloud that surrounds Laputa and catch a time-slip glimpse of Pazu's father. On the Japanese original the entire soundtrack goes silent, strikingly emphasising the impact of the vision and Pazu's reaction to it, but on the American track this sublime moment is invaded by orchestral music, shattering its effectiveness and rending it tonally identical to the scenes that surround it. Professionally recorded and mixed it may well be, but as far as I'm concerned the American track track is a travesty of Miyazaki's original intent.

As with Optimum's release of My Neighbours, the Yamadas, this is a dual format release that includes both Blu-ray and DVD versions of the film, but I'm working from the Blu-ray disc only so I cannot comment on the quality of the DVD transfer.

I've had a number of discussions on the advantages or otherwise of high definition transfers of hand-drawn animation, about whether the increased resolution actually has any significant advantages over a good DVD release of the same. Initially I was sceptical, but have since been won over, and Optimum's Blu-ray of Castle in the Sky has helped to confirm that change of heart. I'm not going to claim that it reveals a previously unseen wealth of picture information, or that it gives the image an eye-popping sharpness, but there is still a precision of detail, a purity of colour and a complete absence of damage or compression artefacts that gives the transfer a richness that DVD just cannot replicate. Being an HD transfer it is also not subject to the NTSC to PAL conversion issues of the previous DVD release.

The PCM soundtracks (stereo for the original Japanese, 5.1 surround for the American English dub) are very clear and boast a good tonal range, though the separation is confined largely to music, and even then is subtly done. The English track is a little beefier on explosions and the reproduction of the orchestral score (which is not on the Japanese version, of course), but there are plenty of times when the Japanese track feels fuller and richer than the 5.1.

Storyboards

In common with many of Ghibli's Japanese DVD releases and their US counterparts, the storyboards for the entire movie have been included here and can be viewed in a window overlaying the main feature. You can select this from the extra features menu and can switch them on and off by pressing the picture-in-picture button. This is a far better option than the slideshow on Optimum's Blu-ray of My Neighbours, the Yamadas, as it allows you to directly compare the rough drafts with the completed artwork and quickly access any specific sequence using the scene selection menu.

Promotional Video (12:38)

A Japanese promotional video from the time of the film's production (Miyazaki looks a lot younger than he does now, whereas producer Takahata Isao looks almost identical to his current self) in which Miyazaki outlines the genesis of the film, and various crew members provide brief sound bites on their roles in the production. Several extracts from the film are included, none of which have dialogue, traditionally the last element to be added in Ghibli features.

Behind the Microphone (4:09)

The usual collection of interviews with the American cast that accompany western releases of Ghibli films, plus some snippets of them recording the voices. Rather engaging, as it happens.

Behind the Studio

Four featurettes produced for the earlier US DVD release, hence the English-language extracts from the film.

The World of Laputa (2:18)

Miyazaki recalls how a visit to Cardiff and the Rhondda Valley helped shape the look and feel of the mining town in the film.

Creating Castle in the Sky (3:40)

Miyazaki talks about the influence of Jules Verne and the early days of Modernism, the inspiration for the flying robots, and the humanitarian message of the film's climax.

Character Sketches (2:39)

Here Miyazaki outlines the origin of the film's two child characters and tells us that "the reason I got into animation was because I wanted to make stories with ordinary children." He reveals that he never wanted to go with mainstream trends and says of the film's initially weak box office, "I don't know why, but when there is a male character without any superpowers, it's not a straightforward crowd pleaser."

Producer's Perspective: Meeting Miyazaki (3:14)

Producer Suzuki Toshio tells an intriguing tale of how his patience and dogged persistence as a writer for an animation magazine eventually allowed him to work with Miyazaki.

Textless Opening and Ending Credits (4:45)

Exactly as it says, allowing you to focus more easily on the drawings and animation.

Original Japanese Trailers (4:05)

Three original Japanese trailers of varying length.

Studio Ghibli Collection Trailers (9:50)

Japanese trailers for Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind (which is actually made before Ghibli was formed) and My Neighbours, the Yamadas, and US trailers for Ponyo, Howl's Moving Castle, Tales From Earthsea, and Spirited Away.

A terrific first film from one of the world's most revered and respected animation studios, one packed with invention and that moves at a sometimes breathless lick, developing its characters in tandem with its narrative and infusing the adventure with humour, humanity and the sort of imagination we too often believe we lose when we move into adulthood. Optimum's dual format package has a decent selection of extras and the picture and sound quality on the Blu-ray disc are first rate. Highly recommended.

The Japanese convention of surname first has been used with all Japanese names.

|